Giganotosaurus

| Giganotosaurus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Skeletal replica of Giganotosaurus in the Australian Museum in Sydney |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Cretaceous (early Cenomanian ) | ||||||||||||

| 100.5 to 96.2 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Giganotosaurus | ||||||||||||

| Coria & Salgado , 1995 | ||||||||||||

| Art | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Giganotosaurus is a genus of theropod dinosaur from the early Upper Cretaceous Argentina .

It was one of the largest known land-dwelling carnivores in the history of the earth . It is counted to the Carcharodontosauridae , a group within the Carnosauria , and was closely related to the genera Carcharodontosaurus and Mapusaurus , which also produced huge species.

So far, a fragmentary skeleton including skull and an isolated fragmentary lower jaw have been found. These finds come from the Candeleros Formation , the oldest member of the Neuquén group , and are thus dated to the early Cenomanian . The only known species is Giganotosaurus carolinii .

features

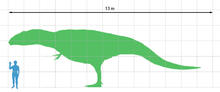

Giganotosaurus is one of the largest known theropods. About 70% of the found skeleton ( holotype ) has survived. Length estimates are 12.2 to 13 meters, while the weight in most studies is 6 to 7 tons. The row of teeth in the upper jaw measures approx. 92 centimeters in length, the thigh bone 136.5 centimeters. 80% of the skull of this skeleton has survived; Length estimates vary from 1.53 to 1.56 meters. However, a recent study suggests that these estimates are probably too high and that the skull was only as long as that of the Tyrannosaurus .

In addition to the holotype skeleton, an isolated lower jaw is known that is 2-8% larger than that of the holotype specimen. Calvo and Coria (1998) suggest that this lower jaw may have belonged to a 1.95 meter long skull. Mazzetta and colleagues (2004) estimate the body weight of this specimen at 8.2 tons. While the holotype specimen was presumably smaller than the largest known skeleton of Tyrannosaurus (" Sue "), according to these researchers, the lower jaw fragment belongs to an animal that was larger than "Sue".

Compared to Tyrannosaurus , Giganotosaurus' bones were overall more robust. The teeth were shorter, more oval in cross-section, and less variable in size than those of Tyrannosaurus . Jack Horner speculates that they were adapted for cutting meat, while Tyrannosaurus' round teeth were more suitable for biting through bones.

Giganotosaurus differs from other theropods in that it has a relatively deep upper jawbone (maxilla), the upper and lower edges of which are approximately parallel to each other. In addition, the square shows two pneumatic openings (foramina). The lower jaw (mandible) has a ventral , downward-pointing tip at the front end ; a characteristic that is otherwise only known from Piatnitzkysaurus . The symphysis is the deepest part of the dental. Other unique features have been described from the brain skull area.

Paleobiology

A biomechanical study by Blanco and Mazzetta (2001) estimates the maximum speed that the animal could reach while running at 14 meters per second (50 km / h). This calculation is based on the assumption that an animal can only run fast enough to maintain its body balance. At higher speeds there would be a risk of falling, which in the case of very large animals can sometimes be fatal due to the smaller ratio between body surface and volume; large animals, for example, have significantly less body surface area to cushion their body mass in the event of a fall.

The skull of the found skeleton is almost completely preserved, which enables a reconstruction of the size and shape of the brain. The brain was relatively long at 27.5 centimeters, but narrow with a maximum width of 7.7 centimeters. The volume is estimated at 275 cubic centimeters. This made the brain significantly smaller than that of the coelurosaurs , such as Tyrannosaurus .

A study by Barrick and Showers (1999) examines isotope ratios of the oxygen in the phosphate of the bones in order to derive conclusions about the metabolism of the animal. These isotope ratios indicate how the body heat was distributed in the skeleton of the living animal. Giganotosaurus, for example, was a homoiothermal (equally warm) animal whose metabolic rate was greater than that of today's reptiles, but lower than that of today's mammals. For an 8-ton Giganotosaurus , these researchers were able to calculate a daily food requirement of 20 kilograms of meat, which corresponds to the requirements of 3 to 4 large lions or tigers .

Paleoecology

The sedimentary rocks that contained the fossils of Giganotosaurus belong to the Candeleros Formation and were deposited in a branched river system about 100.5 to 96.2 million years ago. Giganotosaurus shared its habitat with the dromaeosaurids Buitreraptor and the sauropods Limaysaurus , Nopcsaspondylus and Andesaurus . Finds of gigantic sauropods, as they are known from the somewhat younger Huincul Formation above the Candeleros Formation, have not yet been discovered in the Candeleros Formation. The Huincul Formation contained the remains of Argentinosaurus , possibly the largest sauropod known to date.

Systematics

Giganotosaurus is classified within the Carcharodontosauridae , along with genera such as Carcharodontosaurus , Tyrannotitan, and Acrocanthosaurus . His closest relative was possibly the Mapusaurus, also from Argentina . Coria and Currie combine these two genera as Giganotosaurinae - this name is not used by later authors. Instead, the name Carcharodontosauridae is common to summarize the genera Giganotosaurus , Mapusaurus and Carcharodontosaurus .

History of discovery, finds and naming

The Giganotosaurus fossils were discovered in the region around the Ezequiel-Ramos-Mexía reservoir .

The first find (an isolated, large tooth) was made in 1987 by A. Delgado on the shore of the lake 5 km south of the El Chocón dam . Rodolfo Coria discovered the isolated lower jaw bone (a left dental , copy number MUCPv-95) in 1988 , about 50 km west of El Chocón.

The third find - the well-preserved holotype skeleton (copy number MUCPv-CH-1) - was made by the car mechanic and fossil collector Rubén Carolini in 1993 about 15 km south of El Chocón. This skeleton includes a fragmentary skull, parts of the spine, the full shoulder and pelvic girdle, and a thigh and lower leg, but the arm and foot were missing. The skull bones were found scattered over an area of about 10 square meters, while the rest of the skeleton was found in a slightly disarticulated (partially anatomically related) state. The fossils are kept in the collection of the Museo de la Universidad Nacional del Comahue .

The first description of this genus was published in 1995 by Rodolfo Coria , director of the Argentine Carmen Funes Museum , and Leonardo Salgado in the journal Nature . The generic name is made up of the Greek words gigas - "giant", notos - "south" and sauros - "lizard" and means "giant lizard of the south". The second part of the species name, carolinii , honors the discoverer of the holotype skeleton, Rubén D. Carolini.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Gregory S. Paul : The Princeton Field Guide To Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ et al. 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9 , pp. 97-98, online .

- ^ A b c d Jorge O. Calvo : Dinosaurs and other vertebrates of the Lake Ezequiel Ramos Mexia Area, Neuquen - Patagonia, Argentina. In: Yukimitsu Tomida, Thomas H. Rich, Patricia Vickers-Rich (eds.): Proceedings of the Second Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium (= National Science Museum Monographs. Vol. 15, ISSN 1342-9574 ). National Science Museum, Tokyo 1999, pp. 13-45.

- ^ A b c d e Rodolfo A. Coria , Leonardo Salgado : A new giant carnivorous dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Patagonia. In: Nature . Vol. 377, No. 6546, 1995, 225-226, doi : 10.1038 / 377224a0 .

- ^ A b c d Rodolfo A. Coria, Philip J. Currie : A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina. In: Geodiversitas. Vol. 28, No. 1, 2006, ISSN 1280-9659 , pp. 71-118, digitized version (PDF, 2.92 MB) .

- ^ Frank Seebacher: A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 21, No. 1, 2001, ISSN 0272-4634 , pp. 51-60, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2001) 021 [0051: ANMTCA] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ^ A b François Therrien, Donald M. Henderson: My theropod is bigger than yours ... or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 27, No. 1, 2007, pp. 108-115, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2007) 27 [108: MTIBTY] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ^ A b c d Rodolfo A. Coria, Philip J. Currie: The braincase of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 22, No. 4, 2003, pp. 802-811, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2002) 022 [0802: TBOGCD] 2.0.CO; 2 , digitized version (PDF; 711.91 kB) ( Memento from July 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ A b Matthew T. Carrano, Roger BJ Benson, Scott D. Sampson: The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). In: Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. Vol. 10, No. 2, 2012, ISSN 1477-2019 , pp. 211-300, here p. 233, doi : 10.1080 / 14772019.2011.630927 .

- ↑ a b Jorge Orlando Calvo, Rodolfo Coria: New specimen of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Coria & Salgado, 1995), supports it as the largest theropod ever found. In: Gaia. Revista de Geociências. Vol. 15, 1998, ISSN 0871-5424 , pp. 117–122, digitized version (PDF; 389, 35 kB) ( Memento of the original from March 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked . Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Philip J. Currie, Kenneth Carpenter : A new specimen of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian) of Oklahoma, USA. In: Geodiversitas. Vol. 22, No. 2, 2000, pp. 207–246, (PDF; 1.26 MB) ( Memento of February 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ A b Gerardo V. Mazzetta, Per Christiansen, Richard A. Fariña: Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs. In: Historical Biology. Vol. 16, No. 2/4, 2004, ISSN 0891-2963 , pp. 71-83, doi : 10.1080 / 08912960410001715132 , digital version (PDF; 574.66 kB) .

- ↑ Sean Henahan: Giganotosaurus. (No longer available online.) In: Access Excellence. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014 ; accessed on August 2, 2014 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Thomas R. Holtz Jr. , Ralph E. Molnar, Philip J. Currie: Basal Tetanurae. In: David B. Weishampel , Peter Dodson , Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 71-110.

- ^ R. Ernesto Blanco, Gerardo V. Mazzetta: A new approach to evaluate the cursorial ability of the giant theropod Giganotosaurus carolinii. In: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Vol. 46, No. 2, 2001, ISSN 0567-7920 , pp. 193-202, online .

- ^ Jeff Hecht: Contenders for the crown. In: Earth. Vol. 7, No. 1, 1998, ISSN 1056-148X , pp. 16-17.

- ^ Reese E. Barrick, William J. Showers: Thermophysiology and biology of Gigantosaurus: Comparison with Tyrannosaurus. In: Palaeontologia Electronica. Vol. 2, No. 2, 1999, ISSN 1094-8074 , pp. 1-22, E-Text .

- ^ Peter J. Makovicky , Sebastián Apesteguía, Federico L. Agnolín: The earliest dromaeosaurid theropod from South America. In: Nature. Vol. 437, No. 7061, 2005, pp. 1007-1011, doi : 10.1038 / nature03996 .

- ↑ a b Stephen L. Brusatte, Roger BJ Benson, Daniel J. Chure, Xing Xu , Corwin Sullivan, David WE Hone: The first definitive carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Asia and the delayed ascent of tyrannosaurids. In: Natural Sciences . Vol. 96, No. 9, 2009, pp. 1051-1058, doi : 10.1007 / s00114-009-0565-2 .

- ↑ Giganotosaurus. In: The Paleobiology Database. Retrieved August 2, 2014 .