Gndevank

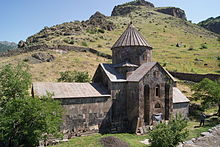

Gndevank ( Armenian Գնդեվանք Gndewank ) is a company founded in the 10th century monastery of the Armenian Apostolic Church in the south Armenian province of Vayots Dzor Province . In the center of the fortified complex is the restored Stefanskirche ( Surb Stephanus ), a cross-domed church dated 936 . There are practically no remains of the large-scale wall paintings that came from the construction period and were added when the monastery was re-founded at the end of the 17th century.

location

Coordinates: 39 ° 45 ′ 31.8 ″ N , 45 ° 36 ′ 38.2 ″ E

Areni is the first larger town in the Vajoz Dzor province on the only M2 expressway coming from the north , which leads from Yerevan to the southern part of the country. 17 kilometers to the east, the M2 running in the Arpa valley crosses the provincial capital Yeghegnadzor and after another 14 kilometers Wajk (Vayk). Seven kilometers east of Wajk in the direction of Sissian, two roads branch off from the expressway parallel to the Arpa to the northeast. The new road (H42) quickly gains height on the eastern slope of the valley cut and after eleven kilometers reaches the village of Gndevaz with 1003 inhabitants according to the statistics for January 2012. The H42 was built around 15 kilometers further at 2108 meters in the mountains To connect the spa Jermuk with the outside world. Six kilometers above Gndevaz is the village of Kechut with the reservoir of the same name, which is fed by the Arpa.

To the west, on the right side of the Arpa, the single-lane old road (H43) follows the course of the Arpa in the increasingly picturesque valley bottom. It crosses the river on the Kechut Dam and there flows into the new street. The continuation of the old road on the west side above the reservoir is no longer passable as far as Jermuk. Dense deciduous forest thrives in the valley, the slopes are overgrown with grass and interspersed with scree slopes of basalt . In some places on the rugged rocks, basalt columns form vertical edges. The monastery is located on the left bank a little above the Arpa at an altitude of 1361 meters and can be reached from the old road in the valley on an asphalt driveway or on a steep footpath that leads down from Gndevaz at the edge of the valley cut. One path ends at the small entrance to the eastern perimeter wall, another comes out further down at a bend in the access road. Grain is grown on the wide plateau around the village and cattle is raised in the meadows.

history

According to excavation finds, the area was already settled in the Bronze Age and Iron Age. A first church could have been built over an older pre-Christian shrine. Before the monastery was founded, monk hermits are said to have lived in the Arpa valley; however, history prior to the 10th century is speculative. The first confirmed year is 936. A founding inscription on the Stefanskirche indicates that the building was built from 931 to 936 on behalf of Princess Sophia, wife of Prince Smbat von Sjunik (historically Sangesur ). Eight inscriptions from the construction period and 22 more from later centuries have been found in Gndevank. In several contemporary and later sources, the place is mentioned by the names Gndevank, Gndavank, Gndavan, Gndevan and Gndevaz. There are several legends about the origin of the name. It is said to come from the monk Supan Gnduni, known for his piety, or from Gunat Ovanes ("the pale Ovanes"), another monk who became the first monastery head in old age. It is also said that Sophia had to sell all her jewelry including her earrings (Armenian gind ) in order to have the monastery built within 40 days. From gind the jewel was Gndevank become. On the west wall she had the inscription affixed: “Vajoz Dzor was a ring without a jewel; I built this church and thus put a jewel in the ring. ”According to the“ Chronicle of the Province of Sjunik ”by the historian Stephanos Orbelian (around 1250–1305), Sophia commissioned the priest Sargis to build the church and the artist Yeghishe Yerets to paint it of the walls, founded the village of Gndevaz and had gardens laid out in the area.

Yeghishe painted the church while it was still under construction, according to Stephanos Orbelian. After its completion, the artist planned the construction of the bell tower together with priest Sargis. In 999, under the abbot Christofor, the Gawit was completed on the west side of the church. In 1008 a (different) priest Sargis had a 22 km long canal built to irrigate the large fields belonging to the monastery. In the first half of the 13th century, Armenia witnessed the first of a series of 15 invasions by the Turkic - Mongolian peoples that lasted until around 1403. The Armenian Orbelian princes ruled largely independently in the south in the 13th century and until the beginning of the 14th century, while the areas in northern Armenia were under Mongolian rule.

In 1309 Abbot Grigor had the monastery renovated. In 1335 the Mongols began devastating power struggles among themselves. After Timur Lenk and his troops marched from Tabriz to Syunik in 1386 and devastated the country, the Armenians found themselves in alternating dependencies between warring powers. The Orbelian family lost its influence during the riots and split into several groups. After large parts of the Armenian population were deported to Isfahan by the Persian Shah Abbas I in 1604 , the monastery was abandoned and large parts of the country remained deserted during the subsequent wars between the Ottomans and Safavids in the 17th century. In 1691, Wardapet Petros had the church restored to re-establish the monastery and the entire complex was surrounded by a fortress wall with round towers.

An earthquake damaged the monastery in 1931, which was vacant during the Soviet reign . The first restorations in the 20th century took place between 1965 and 1970, but remained unfinished so that rain could continue to penetrate the roof and destroy the remaining murals. Further conservation measures followed in the early 1980s. During the work, valuable ritual objects (bronze candlesticks and Chinese celadon ceramics) came to light in a hiding place . The mundane outbuildings have also been restored and made habitable. Two monks living there are (2013) busy with the further expansion.

Monastery complex

The walled monastery grounds are situated on a grass slope sloping to the south with the western wall on the edge of a rocky slope that drops steeply to the Arpa. The northern part of the site is too steep for development; the church is located in the southeastern part of the district that was leveled here. Due to the hillside location, the residential and farm buildings and the refectory are not lined up along the north wall as is usually the case, but together with two round towers form part of the fortress in the south. In the 17th and 18th centuries, monasteries had the task of protecting not only themselves, but also the residents of the surrounding villages from roaming bands of robbers, and were fortified accordingly. The outer walls of the adjoining rooms therefore only have small window slots. A well within the site is essential for medieval monasteries.

Main church

The St. Stephen's Church ( Surb Stepanos ), also the Church of Our Lady ( Surb Astvatsatsin ), is a cross-domed church with cross arms encased in a rectangular shape on the outside and a horseshoe-shaped altar apse in the east, two semicircular closing side arms in the north and south and a rectangular west arm. The basic plan takes up the type of small cemetery churches that were widespread in Armenia in the 7th century, such as Lmbatavank , Karmrawor in Ashtarak or the Church of Our Lady of Talin , on a somewhat enlarged scale . In contrast to those churches, the side arms of which protrude freely on all sides, the St. Stephen's Church has ancillary rooms attached to the side of the altar apse. These are rectangular chambers with small apses and accessible from the side arms. Together with the adjoining rooms, the basic plan results in a partially encased cross-domed church. A further enlargement of this type is represented by the completely rectangular encased central buildings, such as the Anabaptist Church ( Surb Karapet ) of Tsaghats Kar (dated 1041) or the Stefanskirche of the Tanahat Monastery (built 1273–1279). Gndevank was probably the most important church in the region in its time, well before the construction of Noravank (1339), Areni (1321) and Tanahat .

The inner wall corners are spanned by wide belt arches that form a central crossing . In the corners pendentives lead over to the inside circular, outside dodecagonal drum , the dome of which is covered by a conical roof. Only tiny light-colored plaster residues on the black basalt blocks indicate the wall paintings, which Stephanos Orbelian reports. In the Vajoz Dzor and Sjunik region, wall paintings were once widespread, but apart from tiny fragments, only a somewhat larger remnant remained in the main church Peter and Paul of the Tatev Monastery (built 895–906).

On the drum, the wall fields of the four main directions are broken up by narrow, arched windows. The most striking facade design are two deep, vertical triangular niches on the three gable walls, between each of which there is a slightly larger window in a flat niche. The two entrances are in the west and south walls.

Gawit

The Gawit , which was added in front of the west wall in 996 or 999, is one of the earliest examples of a type of building which, in its classic form as a square four-pillar hall (type A1), was characteristic of medieval Armenian church architecture and only occurs here. The forerunners introduced in Vajoz Dzor and Sjunik are long halls covered by a barrel vault, which are classified as type E1. The similar Gawit of the monastery church of Vahanavank further south near Kapan (church from 911, Gawit added in the first half of the 10th century) is only preserved as a ruin.

The slightly ogival barrel vault of the Gawit is structured by two belt arches, which are continued on the side walls in pilasters. In the three wall surfaces in between, semicircular niches of different widths are sunk into the south wall. They correspond to three passages on the north side, which lead into a lower and also barrel-vaulted side room built along the north wall. This type of Gawit cultivation is unique in Armenia. While the adjoining room is completely in the dark, the main room is dimly lit by the open door in the west wall and a window slit above it. A door on the east wall connects the Gawit with the church. In the tympanum semicircle above, an inscription from 1309 reminds of the renovation by Grigor. The western entrance door is set back on the outside in a horseshoe-shaped niche that has one of the building's few ornamental decorations with a threaded rod on the edge. Otherwise, there are some cross motifs in the bas-relief and carvings by pilgrims spread across the outer walls.

In the vicinity of the Gawit there are some khachkars from the 10th to 16th centuries. A gravestone shows a rider with a bow and arrow aiming at two fighting ibexes .

literature

- Jean-Michel Thierry: Armenian Art . Herder, Freiburg / B. 1988, ISBN 3-451-21141-6

Web links

- Rick Ney: Vayot's Dzor. TourArmenia, 2009, p. 26f

- Gndevank Monastery, Vayots Dzor, Armenia. building.am

- Gndevank Monastery. monuments.am

- Gndevank. Armeniapedia

Individual evidence

- ↑ RA Vayots Dzor Marz. (PDF; 255 kB) 2012, armstat.am, p. 309

- ^ Gndevank Monastery. ( Memento of the original from April 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. monuments.am

- ↑ Simon Payaslian: The History of Armenia. From the origins to the present. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2007, p. 103

- ^ Galust Nanyan: Armenia's Crumbling Heritage. Past Horizons, February 22, 2011

- ↑ Jean-Michel Thierry, pp. 324f

- ↑ Rick Ney: Vayots Dzor , p. 27

- ↑ Jean-Michel Thierry, p. 193

- ↑ Stepan Mnazakanjan: Architecture. In: Burchard Brentjes, Stepan Mnazakanjan, Nona Stepanjan: Art of the Middle Ages in Armenia. Union Verlag (VOB), Berlin 1981, p. 79