Greater East Asian Conference

The Greater East Asian Conference ( 大 東 亜 会議 , Dai Tōa Kaigi ) was an international summit from November 5 to 6, 1943 in Tokyo , to which the Japanese Empire invited leading politicians from countries of the so-called Greater East Asian Prosperity Sphere. The occasion was also known as the Tokyo Conference .

The conference addressed a few topics with important content, but was planned as a propaganda showpiece to show the Japanese Empire's commitment to the ideals of the Pan-Asian movement and to highlight its role as the “liberator” of Asia from Western colonialism .

background

From 1931 Japan founded its imperialism under the sign of Pan-Asianism. In 1941, when Japan entered the war against the United States, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the Netherlands, the Japanese presented this as a war for the liberation of all peoples of Asia. In particular, racism was practiced when the Japanese government engaged in propaganda- Cartoons showed Americans and British people as "white devils" or "white demons" equipped with claws, fangs, horns and tails. The Japanese government declared the war to be a racial war between the benevolent Asians, led by Japan of course, and the evil "Anglo-Saxons", the USA and the British Empire, who were considered to be "subhumans". At times, Japanese leaders appeared to believe their own propaganda that whites were in the process of racial degeneration and turning into the drooling, growling creatures of the cartoons. Consequently, Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka said during a press conference in 1940 that "the mission of the Yamato race is to save mankind from becoming evil, to save them from destruction and to lead them to the light of day."

Some inhabitants of the Asian colonies of European powers welcomed the Japanese as liberators. In 1942 in the Dutch East Indies , the nationalist leader Sukarno coined the formula of the three As: Japan, the light of Asia; Japan, the protector of Asia; Japan, the leader of Asia. Although the Greater East Asian Prosperity Sphere heralded an Asia in which all peoples would live together peacefully as brothers and sisters, the planning in the document An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus of July 1943 showed that the Japanese would see themselves as superior " Yamato- Race ”, which was naturally destined to rule the racially subordinate peoples of Asia.

Prior to the Greater East Asian Conference, Japan made vague promises of independence to the various anti-colonial organizations in the areas under its control. Aside from apparent puppet governments in China, these promises have not been kept. Now, as the fronts of the Pacific War turned against Japan, foreign ministry bureaucrats and supporters of Pan-Asian philosophy within the government and the military pushed for territorial "independence" to be accelerated. The domestic resistance against the possible return of the western colonial powers should be increased, as should the support for the Japanese war effort. The Japanese military leadership agreed in principle because they understood the propaganda value of such an endeavor, but the level of "independence" they could imagine was not even that of Manchukuo . Several elements of the Greater East Asian wealth sphere were not affected. Korea and Taiwan were annexed as external territories by the Japanese Empire and there were no plans to grant them any form of political autonomy or even nominal independence. Vietnamese and Cambodian delegates were not invited in order not to snub the Vichy regime as it claimed French Indochina and Japan was still formally allied with it.

The situation in British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies was complex. Large parts were of the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy occupied . The organizers of the Greater East Asian Conference were dismayed by the unauthorized decision by Japanese headquarters to annex these territories on May 31, 1943 instead of granting them nominal independence. These actions undermined efforts to portray Japan as the "liberator" of the Asian peoples. The Indonesian independence leaders Akhmed Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta were invited to informal talks in Tokyo shortly after the conference, but were not allowed to attend the actual conference. Seven countries (including Japan) were ultimately represented.

Attendees

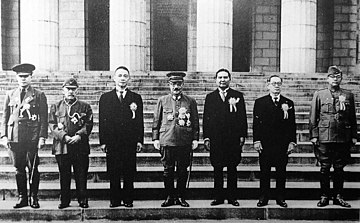

Six "independent" participants and one observer were present at the conference:

- Hideki Tōjō , Prime Minister and de facto military dictator of Japan

- Zhang Jinghui , Prime Minister of Manchukuo

- Wang Jingwei , President of the Reorganized Government of the Republic of China

- Ba Maw , Prime Minister of Burma

- Subhas Chandra Bose , Leader of the Provisional Government of Free India ( Azad Hind )

- José P. Laurel , President of the Second Philippine Republic

- Prince Wan Waithayakon , Envoy of the Kingdom of Thailand

Strictly speaking, Subhas Chandra Bose only participated as an "observer" since India was still under British rule . In addition, the Kingdom of Thailand sent Prince Wan Waithayakon in place of Prime Minister Plaek Pibulsonggram to express that Thailand was not a state under Japanese rule. The prime minister also worried that he might be deposed if he left Bangkok.

Tojo greeted the conference participants with a speech in which he highlighted the "spiritual essence" of Asia, which stood in contrast to the "materialistic civilization" of the West. Their meeting was marked by solidarity and condemnation of Western colonialism, but without any practical plans for economic development or integration. Since Korea was annexed by Japan in 1910, no official Korean delegation attended the conference, but a number of Korean intellectuals, including historian Choe Nam-seon , novelist Yi Kwang-su, and children's book author Ma Haesong. They were part of the Japanese delegation and gave speeches in which they praised Japan and thanked the Japanese for colonizing Korea. The purpose of these addresses was to prepare other Asian peoples for a future in a Japanese-dominated Greater East Asian sphere of affluence. The fact that Choe and Yi were once Korean independence activists who fought bitterly against Japanese rule made their presence at the conference a veritable propaganda coup for the Japanese. It seemed to show that Japanese imperialism was so beneficial to the peoples that even its former opponents saw their mistake. In addition, the Korean speakers condemned the "Anglo-Saxon" powers USA and Great Britain as the worst enemies of Asian civilization ever, and praised Japan as the defender of Asia against the "Anglo-Saxons".

subjects

The main theme of the conference was the need for all Asian peoples to gather behind Japan and provide an example of Pan-Asian idealism against the "white devil". The American historian John W. Dower wrote that the delegations “... placed the war in the context of East versus West, Orient versus Occident, and finally blood versus blood.” Ba Maw from Burma stated: “My Asian blood always called to other Asians ... It is no time for other thoughts, it is the time to think with our blood, and this thinking has brought me from Burma to Japan. "General Tōjō stated:" It is one indisputable fact that the nations of Greater East Asia are held together in every way by an inseparable bond ”. José Laurel from the Philippines mentioned in his speech that no one in the world could prevent a billion Asians from taking their fate into their own hands.

In a joint declaration, the conference participants reaffirmed that the countries of Greater East Asia wanted to ensure the stability of their region through mutual cooperation in order to create a just order for welfare and satisfaction. They wanted to respect the respective independence and traditions and thus enhance the culture in Greater East Asia. The countries wanted to forge friendly relations with the whole world and advocate the abolition of racial discrimination for the good of humanity.

consequences

The November 6th conference and declaration were little more than propaganda efforts to garner regional support for the next phase of the war and to set forth the ideals for which it was waged. On the other hand, the conference also marked a turning point in Japanese foreign policy and relations with other Asian nations. The defeat of the Japanese armed forces in Guadalcanal and an increasing awareness of the limitations of Japan's military strength led the Japanese civilian leadership to adopt a To promote structure based on cooperation rather than colonial dominance in order to achieve greater mobilization of resources against the Allies . It was also the beginning of an effort to prepare a framework for some kind of diplomatic compromise in the event of military failure. However, these efforts came too late to preserve the great empire that had to surrender to the Allies less than two years after the conference.

John W. Dower wrote that Japan's pan-Asian claims were just a "myth" and that the Japanese were just as racist and oppressive towards other Asians as the "white forces" who opposed them. They were even more brutal, as the Japanese treated their supposed Asian brothers and sisters with appalling ruthlessness. For example, many of the Burmese, who welcomed the Japanese as liberators in 1942, missed the British more and more around 1944 because they did not rap and kill Burmese with the same calmness as the Japanese. The Burmese welcomed 1944/45 as liberators from the Japanese. The reality under Japanese rule turned out to be lies in the idealistic statements of the Greater East Asian Conference. Japanese soldiers and sailors often beat up other Asians in public to show who was and who was not a “Yamato race”. In the course of the war, 670,000 Koreans and 41,862 Chinese were forced to do slave labor in Japan under dire conditions. The majority did not survive this experience. About 60,000 people from Burma, China, Thailand, Malaya and the Dutch East Indies as well as around 15,000 British, Australian, Indian and Dutch prisoners of war died as slaves during the construction of the "death railway" between Burma and Thailand. The Japanese behavior towards slaves was based on the old Japanese proverb for the opportune treatment of slaves: ikasazu korasazu (“do not let them live, do not let them die”).

In China, the Japanese were responsible for the deaths of eight to nine million people between 1937 and 1945. Between 200,000 and 400,000 girls, mostly from Korea, but also from other parts of Asia, were used as " comfort women ", as forced prostitutes were called in the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy. The "comfort women" were often severely tortured both physically and sexually. British author George Orwell commented on a radio report: “The best answer to those who say that the cause of Japan is the cause of Asia against the peoples of Europe is: Why do the Japanese keep waging war against other peoples, no less Asians than? are you? ”A deeply disaffected Ba Maw recalled after the war:“ The brutality, arrogance and racial pretensions of the Japanese militarists in Burma have engraved themselves deeply in the Burmese's memories of the war. For a large part of the Southeast Asians, they are all they remember from the war. "

Individual evidence

- ^ Andrew Gordon: The Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present . Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-511060-9 , pp. 211 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993, pp. 244-246

- ^ Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 p. 244

- ^ Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 pp. 244-245

- ^ Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 p. 6

- ^ Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 pp. 263-264

- ^ A b c Smith, Changing Visions of East Asia, pp. 19-24

- ↑ Ken'ichi Goto, Paul H. Kratoska: Tensions of empire . National University of Singapore Press, 2003, ISBN 9971-69-281-3 , pp. 57–58 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Judith A. Stowie: Siam Becomes Thailand: A Story of Intrigue . C. Hurst & Co, 1991, ISBN 1-85065-083-7 , pp. 251 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ WG Beasley, The Rise of Modern Japan , p 204 ISBN 0-312-04077-6

- ^ Andrew Gordon , A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa to the Present , p211, ISBN 0-19-511060-9 , OCLC 49704795

- ↑ a b Kyung Moon Hwang A History of Korea , London: Palgrave, 2010 p. 191

- ↑ Kyung Moon Hwang A History of Korea , London: Palgrave, 2010 pp. 190–191

- ^ A b c Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 p. 6.

- ^ Horner, David The Second World War Part 1 The Pacific , London: Osprey, 2002 p. 71

- ^ Horner, David The Second World War Part 1 The Pacific , London: Osprey, 2002 p. 71

- ^ Joint Declaration of the Greater East Asia Conference

- ^ Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 p. 7

- ^ A b c Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 p. 46

- ^ Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 p. 47

- ^ Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War , New York: Pantheon 1993 pp. 47-48

- ^ Williamson Murray , Allan R. Millett : A War To Be Won , Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2000 p. 545

- ^ Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett: A War To Be Won , Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2000, p. 555

- ^ Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett: A War To Be Won , Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2000, p. 553

literature

- Joyce C. Lebra: Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in World War II: Selected Readings and Documents . Oxford University Press, 1975.

- Ralph Smith: Changing Visions of East Asia, 1943-93: Transformations and Continuities . Routledge, 1975, ISBN 0-415-38140-1 .