Rabbit taboo

The rabbit taboo is a religiously or symbolically based taboo , which relates to the consumption of rabbit meat as a special case of a food taboo , contact with rabbits or the symbolic identification of the animal with negative or positive content. Hasentaboos occur in Near Eastern religious communities close to Islam such as the Alevis , in the form of a dietary law also in Judaism , based on this also with the Alawis , as well as in the popular beliefs of the farmers and nomads of Asia Minor.

Rabbit taboo of the Celtic Britons

Gaius Iulius Caesar reports in Book V, Chapter 12 of De bello Gallico about a rabbit taboo among the Celtic Britons:

“Leporem et gallinam et anserem gustare fas non putant; haec tamen alunt animi voluptatisque causa.

Hare, chicken and goose are considered illegal foods, but these animals are kept for pleasure and pleasure. "

Since Caesar also fell for humorous Celtic interlocutors on other occasions, this tradition must be viewed cum grano salis .

Jewish dietary law

The ban on the consumption of hare meat is one of the binding Jewish dietary laws . In the Torah in the 3rd book of Moses it is written about clean and unclean animals:

“The rabbits ruminate, but they don't split their claws; therefore they are unclean. The hare ruminates too, but does not split its claws; therefore he is unclean for you. And a pig will split its claws, but it won't chew the cud; therefore it shall be unclean for you. You shall not eat of this meat, nor touch its carcass; because they are unclean for you. "

This prohibits the consumption of animals that “do not have split hooves or do not chew on the cud ”.

From the exegesis of the 3rd book of Moses, Mary Douglas extracted further rules that are important for the justification of a food taboo. She lists the following: “To be holy is to be perfect, to be one; Holiness is unity, integrity, perfection of the individual and his kind. The dietary regulations merely develop these rules further as a metaphor of holiness on the same line. ”Farm animals, which belonged to the classic livestock of the Israelites, were, like the land, considered by God blessed. In contrast, the wild animals are not in a God-given bond with humans. However, wild animals can be consumed as long as they have claws and are ruminating. The habit of hares and rabbits to eat their feces is interpreted as ruminating, but they have no claws. On the other hand, pigs fall under the Jewish ban on eating because they have claws but do not chew the cud. "Those animal species are not kosher that are deficient members of their class or whose class itself confuses the general idea of the world." Here, rabbits fall out of the grid of the religious explanation of the world at that time and thus out of the menu.

Ritual purity and symbolism of the hare in Islam

In the various manifestations of the Islamic faith, there are different attitudes to the ritual purity of rabbit meat on the one hand, and to the symbolic occupation of the rabbit on the other. The Alawites also know a food taboo derived from Jewish law . Among the Alevis of the Bektashi - Tarīqa , an Islamic denomination that began with the immigration of Turkmen tribes to Anatolia in the 13th / 14th centuries. Century, and the Alevi Tahtacı the consumption of rabbit meat is ritually forbidden.

The rabbit taboo as a food taboo is characteristic of the Alevi faith, although it still gives rise to diverse speculations and attempts at justification. For the Alevis, hares and rabbits are considered “disastrous animals”, and the prohibition of their consumption is intended to protect the ritual “community unit from the influence of the outside world”. Another approach based on the unclean character of the rabbits traces it back to the fact that “they have a diverse nature composed of characteristics of seven different animals”. This leaves them outside of the biblical animal categories of the book of Genesis and ties in with the taboos in Judaism.

Older traditions of the Turkmen Kizilbash order, from which Alevism derives its origin, may have been preserved in this menu. The formal Shia belief of Kizilbash was to their final submission and distraction, as well as the enforcement of the orthodox-Shia Islam by the Safawidenschah Abbas I by a more superficial binding to Islam and by permanent relationship with a shamanically influenced popular devotion marked.

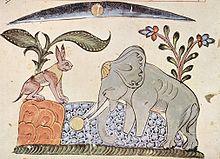

In the visual arts of Islam , including the later Ottoman Empire , the visual representation of the hare played an important, symbolic, mythologically based role. Turkish authors refer to this with the aim of integrating the Alevi community into the Turkish nation.

The ban on eating rabbit meat does not apply to the majority of Muslims , who claim that there was no such ban. In sura 6: Al-An'am of the Koran it says:

“Say: I find nothing in what has been revealed to me that has been forbidden to a person who eats it, unless blood or swine that has died or spilled out of its own accord, for that is defilement or iniquity.”

The permissibility of the consumption of hare meat is continued in the hadithic tradition:

“Hammad Ibn Uthman reported that Imam Ja'far As-Sadiq said: The Prophet Muhammad was of a reticent nature and he used to detest something without declaring it forbidden. When the hare was brought to him, he detested it, but did not declare it forbidden himself. "

Symbolic meaning in Christianity and Christian sects

With reference to the Gospel of Mark ( Mk 7.18–19 EU ) and the Pauline letters ( 1 Cor 10.25 EU , 1 Tim 4,4 EU ), Christianity knows no dietary laws. However, since the time of early Christianity, the hare had a variety of symbolic meanings. Since the Vulgate Translation of the Psalm verse Ps 104,18 EU by Jerome , the "Shaphan" (literally, the original Hebrew Hyrax ) on grounds translated better course for the former Bible reader with "lepusculus" (Bunny), the rabbit is a symbol of the individual Christian who seeks refuge in God the rock. Here lies one of the roots of the cultural tradition of the Easter bunny , which is also reflected in profane modern society in the custom of eating a bunny at Easter .

The Chaldeans see the encounter with a hare as an unfavorable omen. Pregnant women should avoid encounters with rabbits as much as possible, so that their children do not stay open when they sleep. The hare is also considered unclean by the Nestorians .

The symbolic meaning of the hare as a pagan fertility symbol leads the Jehovah's Witnesses to view Easter as originally a pagan fertility festival, which is why they reject the celebration of Easter.

Medical context

The observation that there is a connection between the consumption of certain types of meat and the appearance of symptoms of illness probably goes back to a time when the majority of people lived as hunters and gatherers . These early societies had developed their own strategies for dealing with a one-sided diet threatened by a lack of food, especially in late winter and early spring. This included avoiding very low-fat, but excessively protein-rich malnutrition , as can occur, for example, when only eating bison or rabbit meat. In modern times, the polar explorer Vilhjálmur Stefánsson first described the predominant consumption of rabbit meat as the cause of such malnutrition, the so-called rabbit hunger . The empirical knowledge was raised to the metaphysical level of belief and led to the tradition of religious food taboos .

Another possible medical explanation for tabooing rabbit meat is the risk of parasitosis or bacterial infection. The danger of trichinella - often cited in connection with the Old Testament dietary laws - is more relevant for the consumption of carnivorous animals or omnivores such as pigs . In contrast, the consumption of undercooked meat from wild rabbits or hares carries the risk of developing tularemia .

literature

- Klaus E. Müller : Cultural-historical studies on the genesis of pseudo-Islamic sect formations in the Middle East . Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1967, p. 331-333 . , Chapter heading: "The rabbit taboo".

- Not by bread alone, New York, MacMillan 1946; expanded edition under the title The Fat of the Land, New York, Macmillan, 1956, second edition 1961

supporting documents

- ↑ a b Klaus E. Müller : Cultural-historical studies on the genesis of pseudo-Islamic sect formations in the Middle East . Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1967, p. 331-333 .

- ↑ Gaius Iulius Caesar: The Gallic War . Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf & Zürich 1999, ISBN 3-7608-1718-1 , p. 204 .

- ↑ See the description of the elk hunt by sawing off the sleeping tree, Bellum Gallicum VI, 27. See also Herkynischer Wald # Fauna

- ↑ In the biblical book of Psalms ( Ps 104,18 EU ) and Proverbs ( Prov 30,26 EU ), from the late antique translation of the Vulgate by Hieronymus, the "hare" was spoken of, seeking refuge in the rock. In the original Hebrew text it says “schafan” (literally: hyrax ), Hieronymus translated this term with “lepusculus” (bunny). The decisive factor for his choice of words was probably the fact that there are no rock hyraxes north of the Alps, and the translators - including Martin Luther later - wanted to use terms that were known to their readers. It was only in the revision of the Luther Bible in 1987 that the rabbit became the hyrax again.

- ^ Source of translation online

- ^ A b Mary Douglas: Purity and Danger - Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. (PDF) 1966, p. 55 , archived from the original on August 17, 2013 ; accessed on March 27, 2016 (English): “To be holy is to be whole, to be one; holiness is unity, integrity, perfection of the individual and of the kind. The dietary rules merely develop the metaphor of holiness on the same lines. "

- ^ Mary Douglas: Purity and Danger - Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. (PDF) 1966, p. 56 , archived from the original on August 17, 2013 ; accessed on March 27, 2016 (English): "Those species are unclean which are imperfect members of their class, or whose class itself confounds the general scheme of the world."

- ↑ Langer, Robert, Alevitische Rituale, pp. 65-108, in: Sökefeld, Martin: Aleviten in Deutschland: Identity Processes of a Religious Community in the Diaspora, Bielefeld 2008, p. 77

- ↑ Gümüs, Burak: Turkish Alevites - From the Ottoman Empire to Today's Turkey, Konstanz 2001, p. 54

- ↑ Bumke, Peter J .: Kızılbaş Kurds in Dersim (Tunceli, Turkey): Marginality and Heresy, pp. 530-548, in: Anthropos, Vol. 74, H. 3./4. (1979), p. 535

- ↑ a b Krisztina Kehl-Bodrogi: The Kisilbaş / Alevis. Research on an esoteric religious community in Anatolia. Dr. Klaus Schwarz, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-922968-70-8 , pp. 233 .

- ↑ Sholeh A. Quinn: Iran under Safawid rule. In: David O. Morgan, Arthur Reid (eds.): New Cambridge History of Islam Vol. 3: The Eastern Islamic world - Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2000, ISBN 978-0-521-83957-0 , pp. 218-223 .

- ↑ Hans Robert Roemer: The Turkmen Qizilbas: Founders and victims of the Safavid theocracy. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society . Vol. 135, 1985, pp. 227–240, here specifically p. 236 (PDF file; 1.49 MB, accessed on March 29, 2016).

- ↑ Pervin Ergun (2011): Alevilik Bektaşilikteki Tavşan İnancının Mitolojik Kökleri Üzerine (Mythological roots of the views of the Bektaschi Alevis about the rabbit) . In: Turkish Culture & Haci Bektas Veli Research Quarterly 60 (October 2011), p. 281 online (Paywall, English summary), accessed on March 29, 2016

- ^ Source of translation online

- ↑ Basile Nikitine: Superstitions of Chaldéens du plateau d'Ourmiah . Société Française d'Ethnographie, 1923, p. 172-173 . , quoted from Müller, 1967

- ↑ C. Sandreczki: Journey to Mosul and through Kurdistan to Urumia, Volume 2 . Nabu Press (photomechanical reproduction), Charleston, South Carolina, ISBN 978-1-276-02149-4 , pp. 138 .

- ↑ Jehovah's Witnesses: What Does the Bible Say About Easter? , accessed March 29, 2016

- ↑ JD Speth, KA Spielmann (1983): Energy Source, Protein Metabolism, and Hunter-Gatherer Subsistence Strategies (PDF; 2.0 MB, accessed on March 29, 2016), in: Journal of Anthropological Archeology 2, 1983, p. 1–31, on rabbit meat: p. 3

- ↑ Rabbit hunger as malnutrition

- ↑ Robert Koch Institute , Epidemiological Bulletin 07/2007 PDF (204 kB) , accessed on March 29, 2016