Holy Sepulcher Aedicule

The Holy Sepulcher Aedicula is a small structure ( aedicula ) that is located in the center of the Constantinian rotunda of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. It has been rebuilt four times over the centuries.

Inside the today's aedicula there are two rooms: an anteroom (the so-called angel chapel or angel room) and the actual burial chamber. A narrow, about one meter wide and long passage leads from the Angel Chapel to the burial chamber. The Coptic Chapel is built onto the back of the Holy Sepulcher Aedicula from the outside.

Constantinian Aedicula (4th century)

The burial chamber, venerated as the tomb of Christ and the place of the resurrection , had already been carved out of the rising rock mass before the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher under Emperor Constantine . This kind of highlighting grave caves is attested several times, an example is the Absalomgrab in the Kidron Valley . This exposure resulted in a house-like structure made of natural rock, which was also given architectural elements; Eusebius described it as a decorated, pillared rock grotto.

This sanctuary was incorporated into the monumental Constantinian Church of the Holy Sepulcher and designed according to its importance. John Wilkinson reconstructed the Constantine aedicula based on a (fragmentary) miniature model from the 6th century that was found in Narbonne . It was therefore a two-part system:

- There was still a remnant of the grown rock, namely a round burial house with the burial chamber inside. This rock was made into a polygonal chapel with pillars at the corners; it was crowned by a pyramidal roof with a cross on top.

- Access was through a rock grotto; this entrance area had been extended to a grave temple with pillars that supported a roof. The gable was adorned with a shell-shaped dome. A metal grille separated the entrance area.

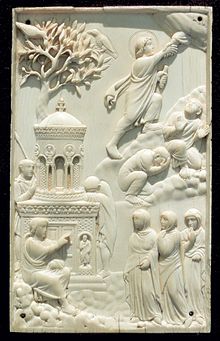

This sanctuary is described by the various pilgrimage reports of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. There are artistic representations, for example, on pilgrim bottles from Monza and Bobbio .

The conquests of Jerusalem by the Persians (614) and the Muslims (638) survived the grave pedicle without major damage. The Gallic Bishop Arkulf (9th century) described it, linguistically somewhat awkward, as a “round hut carved into the rock.” The copy of the Holy Sepulcher in the Cathedral of Aquileia was based on contemporary architectural drawings that go back to Arkulf's pilgrimage. Inside, to the left of the entrance, the circular ashlar building in Aquileia has an arcosol tomb .

The end of the building came in 1009 under the caliph al-Hakim . Jachja ibn-Saˁid reported as a contemporary witness: a certain Abu Dahir “tried very hard to uncover the tomb and completely remove its traces. To do this, he dug up most of it and tore it off. "

Byzantine aedicule (11th century)

Peace treaties made it possible for Emperor Constantine IX to restore the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. However, the grave pedicle was lost due to the destruction under al-Hakim, and in 1048 a new building was built.

The Russian abbot Daniel (around 1106/07) described a marble burial chapel, adorned with twelve columns and crowned by a turret. The interior was a very small, low rock grotto with a rock bank. Through three holes he could take a look at the grown rock of the burial chamber; there was nothing left of it.

This new building took up an old iconographic tradition, which had depicted the Holy Sepulcher as a cuboid structure with filigree roof turrets on pillars (example: Reider's table ) in contradiction to the real appearance of the Constantinian aedicule. Instead of reconstructing the destroyed building as it had been, it was more attractive to put something new in its place, following this iconographic tradition.

The Crusaders made major changes to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, but left the aedicula unchanged. The Crusades increased interest in the world of the Bible in Western Christendom. In the replicas of the Holy Sepulcher , which have now been made in large numbers, the Constantinian rotunda was sometimes copied (albeit considerably reduced in size), and sometimes the grave pedicle, which was also possible on a 1: 1 scale.

The filigree roof turret gave these holy graves an oriental look. In the case of the original in Jerusalem, it served a practical purpose: to shield the smoke outlet from the vaulted burial chamber, because the Anastasis rotunda was in ruins and the aedicula was thus in the open air.

Franciscan Aedicule (16th Century)

Due to the open rotunda roof, the grave pedicle was exposed to the weather, which in the late Middle Ages led to its structural fabric deteriorating. The earthquake of 1545 caused additional damage. After more than 500 years, the Holy Sepulcher Aedicula, close to collapse, was demolished and rebuilt in 1555 under the Guardian Bonifatius von Ragusa OFM. However, no new architectural creation was planned, but a replica of the previous building. The Franciscan building is very well documented by true-to-scale drawings and plans by Bernadino Amico OFM (1593).

The length of the chapel was 8.30 m, the width at the entrance front about 5.10 m, at the transition to the polygonal end even almost 6.45 m. The angel chapel (anteroom) was about 4.50 m high, the burial chapel behind it about 20 cm higher. The roof attachment was 6 m high, so the entire Holy Sepulcher Chapel was almost 11 m high.

However, Amico had not reproduced the details of the building realistically, but left them partly out, partly aesthetically improved in his judgment. The illustrations in Elzearius Horn , Ichnographiae locorum et monumentorum veterum Terrae Sanctae give a more realistic impression . Almost all copies from the Counter-Reformation and Baroque periods refer to this chapel. The most exact copy of the original in Jerusalem is in Slaný in the Czech Republic .

The Franciscans maintained at its offices in Jerusalem and Bethlehem craftsman schools where Palestinian artists replicas of the Holy grave chapel of olive wood with inlays of mother of pearl created. They have been sold as pilgrim souvenirs since 1593.

Rococo Aedicule (19th Century)

On the night of October 11th to 12th, 1808, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was badly damaged by a major fire. The burning roof of the rotunda collapsed onto the Holy Sepulcher aedicule. This fire received little attention in Europe, and so it was possible for the Greek Orthodox Church to enforce a greater presence of its denomination in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher during the restoration.

The architect was Michael Komnenos from Istanbul . Despite Franciscan protests, the damaged burial chapel from the 16th century, 1809–1810, was replaced by a “divine chamber” (θεῖον Κουβούκλιον, theĩon Kouvoúklion ) in the Turkish Rococo style . Komnenos standardized the structure of the chapel, which had been divided into two parts. The building, which is rectangular at the front and rounded at the back, has a floor area of around 8.30 × 5.90 m. In fact, this chapel incorporates elements of the previous building, which is less noticeable due to the architectural style chosen: the marble cladding, the structuring of the outer walls with columns and pilasters, the crowning of the roof with small columns and dome. Rearwardly of the band is Copt grown; the entrance area looks relatively overloaded with large candelabra, lamps, pictures and inscriptions.

Inside, Komnenos received the burial chamber (about 2 × 2 m) that had survived the fire, as well as the only 1.35 m high, about 1 m long passage, and designed the so-called angel room (about 3.40 × 3.90 m ) New. The Holy Sepulcher Chapel still exists in this form today.

In the 20th century, damage had become noticeable, which meant that the chapel had to be supported with steel girders since the end of the British mandate (1947). The decay continued, however, the stones cracked and the building warped. In February 2015, the Israeli police closed the chapel for a few hours to draw attention to the need for restoration. A report from the Technical University of Athens confirmed the need for renovation. The costs were estimated at three million euros, of which the Greek Orthodox, Armenian and Roman Catholic Churches each paid a third and King Abdallah II of Jordan donated an additional 100,000 euros - the old city of Jerusalem belonged to Jordan until 1967, and Jordan sees itself as responsible for the holy places to this day. Project manager Antonia Moropoulou and her team were only concerned with the restoration and conservation of the existing structure: “Replace porous stones, completely replace part of a wall, spray cracks in the rock with special mortar, fix marble slabs with metal pins. In future, the grave should also be earthquake-proof. ”An archaeological investigation was not part of the project. The original schedule could be adhered to, on March 22, 2017, in time for Easter, the end of the restoration work was celebrated.

Replicas

Holy grave in Görlitz

Copy of the Byzantine aedicula shortly before its demolition.

Holy grave in Slaný

Copy of the Franciscan aedicula.

literature

- Max Küchler : Jerusalem. A handbook and study guide to the Holy City , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 .

- Michael Rüdiger: Replicas of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem during the Counter Reformation and Baroque. A contribution to the cult history of architectural devotional copies , Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2003, ISBN 3-7954-1600-0 .

- Klaus Bieberstein : The Church of the Holy Sepulcher through the ages . In: World and Environment of the Bible 1/1996, pp. 35–43.

- Max Küchler: “What are you looking for the living among the dead?” The grave of Christ. In: World and Environment of the Bible 2/2000, pp. 38–43.

- John Wilkinson: The Tomb of Christ: An Outline of its Structural History.

Web links

- National Geographic Exclusive - Tomb of Jesus Christ Uncovered for the First Time in Centuries (October 26, 2016)

- National Geographic: Exclusive - Age of Holy Sepulcher of Jesus Christ Determined (October 28, 2016)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 477 .

- ↑ a b Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 434 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 438 (The 1.24 m high marble block is in the Musée Archéologique de Narbonne).

- ↑ a b Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 436 .

- ↑ Klaus Bieberstein: The Church of the Holy Sepulcher . S. 39 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 444-446 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 446 .

- ↑ Michael Rüdiger: Replicas . S. 13 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 448 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 449-450 .

- ↑ Klaus Bieberstein: The Church of the Holy Sepulcher . S. 42 .

- ↑ Michael Rüdiger: Replicas . S. 10 .

- ↑ Michael Rüdiger: Replicas . S. 11 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 455-456 .

- ↑ Michael Rüdiger: Replicas . S. 30 .

- ↑ Michael Rüdiger: Replicas . S. 32-33 .

- ↑ Michael Rüdiger: Replicas . S. 230-231 .

- ↑ Michael Rüdiger: Replicas . S. 50 .

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 457 .

- ↑ a b c Max Küchler: Jerusalem . S. 477 .

- ↑ Michael Rüdiger: Replicas . S. 11-12 .

- ↑ a b c Stefanie Järkel (dpa): In the future earthquake-proof. In: domradio.de. August 5, 2016, accessed March 1, 2018 .

- ↑ KNA: building at the place of resurrection. In: domradio.de. March 15, 2017, accessed March 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Andreas Krogmann (KNA): Historical moments in chord. In: domradio.de. March 22, 2017, accessed March 1, 2018 .