The Hessian country messenger

The Hessischer Landbote is an eight-page pamphlet against the social grievances of the time, originally written by Georg Büchner in 1834 and printed and published after editorial revision by the Butzbach Rector Friedrich Ludwig Weidig . The first copies of the pamphlet were secretly distributed in the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt on the night of July 31, 1834 . The pamphlet is known for its appeal: “Peace to the huts! War on the palaces! "

content

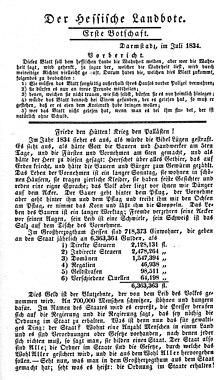

The pamphlet begins after a short “preliminary report” (with instructions to the readers on how to best handle the illegal text) with the appeal: “Peace to the huts! War on the palaces! ”The circulation of the pamphlet is not known, it was probably in the range of 1200 to 1500 copies.

The authors compare the social conditions in Hesse at that time with a (modified) example from the creation story of the Bible by provocatively asking whether - contrary to what is reported in Genesis - the “peasants and craftsmen” were created on the fifth instead of the sixth day and therefore to be attributed to the animals, which could be controlled at will by the people created on the sixth day, "the princes and nobles". In addition, the authors denounce the judiciary as the "whore of princes"; it is "only a means to keep yourself in order so that you are better offended."

The basic motif of this pamphlet, which runs as a red thread through the entire text, is the connection of this biblical style with the listing of numbers about the (high) tax receipts and (senseless) expenses of the Grand Duchy of Hesse . So Büchner and Weidig tried to convince the believing people of the urgency of a revolution and the justification of an uprising against the Grand Duke and the state order - given at the time "by God's grace" and thus inviolable.

Creation and distribution of the pamphlet

It is believed that the draft for the pamphlet by Georg Büchner was written in the second half of March 1834 at the Gießener Badenburg and revised by Friedrich Ludwig Weidig in May. Between July 5th and 9th Georg Büchner and a companion brought the revised text to the printer in Offenbach am Main . On July 31, Karl Minnigerode , Friedrich Jacob Schütz and Karl Zeuner picked up the printed copies of the Landbote from the Carl Preller printing works to distribute them. A spy named Johann Konrad Kuhl informed the police about the explosive writing. The very next day, August 1st, Karl Minnigerode was arrested with 139 copies of the Landbote in his possession . Büchner warned Schütz, Zeuner and Weidig about police activities. Non-confiscated copies were subsequently redistributed.

The pamphlet , the first printed version of which was created in Offenbach, was revised once more by Leopold Eichelberg and reprinted in Marburg in November . Whole passages were partially removed or added during the revisions. For example, if you compare the versions from July and November 1834, the November version lacks the introductory text mentioned above, and the pamphlet begins directly with the appeal “Peace to the huts ...”. Büchner's original text has not survived. The starting point for research is the form that Weidig first reworked. According to reports, Büchner was furious about the changes Weidig made and no longer willing to accept the text as his. This suggests that the changes were relatively massive. In the second part in particular, Büchner research suspects that Weidig's interventions were most of the time, without whose help the pamphlet could not have appeared.

consequences

The attacked authorities reacted violently to the appearance of the leaflet. Büchner was wanted on a wanted list, but was able to flee across the French border to Strasbourg in 1835 . Weidig, now pastor in Ober-Gleen after a forced transfer , was arrested along with other members of the opposition. First he was imprisoned in Friedberg , then in Darmstadt. There he was subjected to inhumane conditions of detention, tortured and died in 1837 under circumstances that were never fully understood. The official investigation found suicide (by opening the wrists).

A forensic medical report drawn up by the University of Heidelberg in 1975, which naturally could only be a reassessment of the findings described, confirmed this and pointed out that the death was partly caused by failure to provide assistance. The fall and death of "Pastor Weidig" became a political weapon in the 1840s, especially in liberal campaigns against the so-called "secret Inquisition" and for jury courts. There were also rumors of outside interference, including murder allegations, which can neither be proven nor refuted. So-called "new examinations" lack the essential basis, namely the availability of independent sources.

rating

The Hessian Landbote is to be understood as a revolutionary call to the rural population, both against the aristocratic upper class and (at least in Büchner's original) against the rich, liberal bourgeoisie , whereby Weidig is said to have later replaced Büchner's term "the rich" with "the noble", in order to weaken the latter criticism in particular, and not to alienate the liberal allies.

Historically preceded was the Hambach Festival , where opposition members from all walks of life met but could not agree on a common action against the ruling class. This became clear in the poorly organized and therefore quickly suppressed Frankfurt Wachensturm . An agreement on a broad level could not be reached in particular because the liberal bourgeoisie was repeatedly fobbed off with small concessions and promises from the nobility. But this was useless for the poor and hungry Hessian rural population, who drew attention to themselves through occasional protests, but which, like the Södel bloodbath in 1830, were violently suppressed.

That is why the peasants in the Landbote were called upon to lead a revolution against both the ruling and the property classes. According to Büchner, “only the necessary needs of the large masses can bring about changes”. In later writings Büchner expresses himself even more clearly, perhaps more resignedly, for example in a letter to Gutzkow he expresses his belief that the people cannot be moved to revolution through idealism: “And the big class itself? For them there are only two levers, material misery and religious fanaticism . ”Even without religious fanaticism, Büchner and Weidig in the Hessischer Landbote use these two levers to win over“ the big class ”for their goals: the authors lead the farmers material misery in particular in contrast to "the noble" in mind and at the same time provide a religious justification for the desired uprising.

The Hessischer Landbote is one of the most important works of the Vormärz . Thomas Nipperdey described it as the first major manifesto of a social revolution.

Literature / sources

- Georg Büchner, Ludwig Weidig: The Hessian country messenger. Texts, letters, trial files . Commented by Hans Magnus Enzensberger. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1965 (Coll. Insel 3).

- Georg Büchner: Works and Letters. Munich edition . Edited by Karl Pörnbacher u. a. 8th edition. Hanser, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-446-12883-2 ; as paperback: dtv, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-423-12374-7 .

- Gerhard Schaub: Georg Büchner / Friedrich Ludwig Weidig. The Hessian country messenger. Texts, materials, comments . Hanser, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-446-12196-X (= series Hanser. Literature Comments , Volume 1).

- Thomas Michael Mayer: Büchner and Weidig - early communism and revolutionary democracy. To the text distribution of the Hessischer Landbote . In: Heinz Ludwig Arnold (Ed.): Georg Büchner I / II . München 1979 (text + criticism. Sonderband), pp. 16–298. ISBN 3-921402-63-8

[in the 2nd, improved and increased by one index edition 1982, pp. 16–298 u. 463] - Gerhard P. Knapp: Georg Büchner . 3rd, completely revised edition. Stuttgart: Metzler 2000. ISBN 3-476-13159-9

- Georg Büchner: Writings, letters, documents . Edited by Henri Poschmann with the collaboration of Rosemarie Poschmann. Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag (in the paperback volume 13) 2006. ISBN 978-3-618-68013-0 , ISBN 3-618-68013-9

- Thomas Michael Mayer u. a. (Arrangement): Georg Büchner. Life, work, time. An exhibition on the 150th anniversary of the "Hessischer Landbote". Catalog / with the assistance of Bettina Bischoff u. a. edit by Thomas Michael Mayer, Marburg 1985

[2. significantly improved u. increased edition 1986; 3rd edition 1987] - Markus May, Udo Roth, Gideon Stiening (eds.): Peace to the huts, war to the pallets! The Hessian Landbote from an interdisciplinary perspective. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2015, ISBN 978-3-8253-6456-4 .

Web links

- The Hessian Landbote at Zeno.org .

- Manfred Koch Georg Büchner's 200th birthday, The Sweat of the Poor , NZZ , October 19, 2013

- Content, origin, meaning, effect

- Xlibris interpretation

- Der Hessischer Landbote - Visual interpretation by ARBOS - Society for Music and Theater

- Video about the Hessian country messenger

Individual evidence

- ^ Karl Brinkmann: Explanations on Georg Büchner: The Hessian Landbote, Lenz, Leonce and Lena. Hollfeld / Obfr., Bange, 1968.

- ↑ Georg Büchner and Carl Preller (older brother of Joh. Friedrich Preller the Elder), painters, in Weimar

- ^ Carl-Georg Büchner Jahr ( Memento from December 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Helmut Preller took part in the reading in Offenbach

- ^ Portrait of Georg Büchner In: hoespielhelden.de , requested on July 2, 2009

- ^ Karl Pörnbacher (editor): Georg Büchner. Works and letters, Munich edition. ISBN 3-423-02202-7 pp. 408-409

- ^ Letter to the family, June 1833. From: Georg Büchner: Werke und Briefe . Munich edition. Karl Pörnbacher u. a. [Ed.]. 8th edition. Munich 2001 [dtv], p. 280.

- ↑ June 1836; ibid. p. 319

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey : German History 1800–1866. Citizen world and strong state. CH Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 340609354X , p. 373