Japan Air Lines flight 123

| Japan Air Lines flight 123 | |

|---|---|

|

The later crashed machine JA8119 , 1984 |

|

| Accident summary | |

| Accident type | Structural failure in flight |

| place | Takamagahara Mountain, Gunma Prefecture , Japan |

| date | August 12, 1985 |

| Fatalities | 520 |

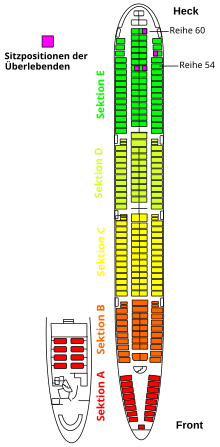

| Survivors | 4th |

| Injured | 4th |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-100SR |

| operator | Japan Air Lines |

| Mark | JA8119 |

| Departure airport |

|

| Destination airport |

|

| Passengers | 509 |

| crew | 15th |

| Lists of aviation accidents | |

Japan Air Lines flight 123 ( flight number after the IATA airline code : JL123 ) was a scheduled domestic flight of the Japanese airline Japan Air Lines from Tokyo-Haneda Airport to Osaka-Itami Airport , on which a Boeing was on August 12, 1985 747-146SR at an altitude of 1460 m at two ridges of the mountain Takamagahara in Japanese Gunma Prefecture crashed. Of 524 people on board, only four survived. This is the worst aircraft accident to date with only one single machine involved. August 1985 is still the month with the highest number of fatalities from accidents in civil aviation ( more people were killed in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 ). In the same month Delta Air Lines flight 191 (on August 2, 1985 in Dallas : 134 dead) and British Airtours flight 28M (on August 22 in Manchester : 55 dead) also had an accident .

plane

The aircraft with the air vehicle registration number "JA8119" was a Boeing 747-100SR . The machine made its first flight on January 28, 1974 (11 years and 7 months old at the time of the crash). Before the machine crashed, it had flown 25,030 flight hours. It was equipped with four Pratt & Whitney engines.

Flight history

The Boeing 747 took off from Tokyo Haneda International Airport for Osaka Itami Airport on August 12, 1985 at 6:12 pm. On board were the 15-man crew and 509 passengers, including the Japanese singer Kyū Sakamoto . The flight time should be 54 minutes as planned.

The machine had just climbed to its cruising altitude of 7,300 m when an explosion could be heard from the stern. As a result, the pressure in the cabin dropped rapidly . The pilots made an emergency call . The crew assumed that the aircraft had lost a tailgate. In fact, the vertical stabilizer was torn down and the four-fold hydraulic control system for steering the aircraft was destroyed. After the crew had increasing problems keeping the machine under control, they first requested permission to fly back to Haneda, then to land at Yokota Air Base in the United States, and finally again for Haneda. During the descent to 4100 m, the crew reported flight behavior that was no longer controllable. The crew extended the landing gear to stabilize the aircraft. The Boeing continued to descend to 2100 m until the pilots managed to climb to 4000 m. Without a functioning hydraulic steering system, the crew could only maneuver the machine using the engine thrust. Several up and down movements followed, during which the crew tried to control the machine. During this time, several passengers wrote short farewell lines to their relatives. The machine crashed at an altitude of 1,460 m on Takamagahara Mountain in Gunma Prefecture . First the right wing brushed a mountain ridge, then the plane turned on its back and then crashed on another mountain ridge.

Delayed rescue operations

United States Air Force air traffic controllers at Yokota Air Base , near the flight path of JL123, had been listening to the radio traffic and calls for help. They kept in contact with the Japanese control authorities and cleared their runway for the aircraft. After losing radar contact, a C-130 Hercules from the 345th Air Transport Squadron was asked to search for the lost aircraft. The C-130 crew was the first to discover the crash site just 20 minutes after the crash, while it was still daylight. She notified Yokota Air Base and directed a USAF Huey helicopter from Yokota to the crash site. Rescue teams were formed to lower Marines on ropes from helicopters. The help offered by the USAF to lead the Japanese to the scene of the accident as quickly as possible and to help with the rescue operation was rejected by the Japanese authorities. Instead, the Americans were ordered to return to the base, as the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) wanted to carry out the rescue operations alone.

A JSDF helicopter finally discovered the wreck during the night, but was unable to land at the crash site due to poor visibility and mountainous terrain. From the air, the pilots reported that there were no signs of survivors to be seen. Based on this report, the rescue workers were allowed to spend the night in a village 68 km away and did not advance to the crash site until the next morning. In the meantime, numerous passengers who had survived the crash died from their injuries or from hypothermia. A doctor said that if you had come 10 hours early you could have helped many people.

Yumi Ochiai, one of the four survivors, said in the hospital bed that she saw bright lights and heard rotor noises shortly after waking up between the wreckage. She tried in vain to draw attention to herself. In addition, she could hear the screams and groans of many other survivors. During the night these noises became less and less.

Cause and consequences

During the repair after a tail strike at Osaka International Airport on June 2, 1978, a repair was made on the pressure bulkhead in the rear of the machine with a single row of rivets instead of the double row as required . This repair was carried out by Boeing . The catastrophe occurred 12,319 landings after this repair: At an altitude of around 7,300 m the pressure bulkhead burst , with the cabin pressure discharging into the tail unit and then the vertical tail unit literally blasting off. As a result of the crash, Yasumoto Takagi resigned from his post as President of Japan Air Lines. The Boeing employee responsible for incorrect maintenance in Haneda committed suicide .

The accident on Japan Air Lines flight 123 was dealt with in the Canadian television series Mayday - Alarm in the cockpit in the episode Jumbojet out of control (original title: Out Of Control ). In simulated scenes, animations and interviews with bereaved relatives and investigators, reports were made about the preparations, the process and the background of the flight.

The flight was also featured in the play (1999) and later feature film (2013) Charlie Victor Romeo .

See also

- Aloha Airlines Flight 243 : Loss of part of the fuselage

- United Airlines Flight 232 : A flight with similar tax problems that crashed on July 19, 1989, with 111 dead and 172 injured.

- Shelling of the Airbus A300 OO-DLL of European Air Transport : so far the only flight with similar control problems that succeeded in a successful emergency landing

- United Airlines Flight 811 : explosive decompression

- American Airlines Flight 96 : Cargo Hatch Failure

- Pan Am Flight 125 : Cargo hatch failure

- British Airways flight 5390 : Partial loss of the cockpit glazing, causing decompression

- British European Airways Flight 706 : On the 12-year-old machine, the rear pressure bulkhead was weakened by corrosion and failed.

- Turkish Airlines Flight 981 : explosive decompression due to the failure of a cargo hatch on a DC-10 due to improper closure and subsequent crash

- China Airlines Flight 611 : The fuselage section was torn down as a result of damage that was not properly repaired after Tailstrike

Web links

- Animated explanation of the repair error , (English)

- Investigation report of the Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission (AAIC) (PDF, 55 MB, English)

- AAIC investigation report (Japanese)

- Chris Kilroy: Special Report: Japan Airlines Flight 123. Airdisaster.com, 2008, archived from the original on July 2, 2011 ; accessed on August 12, 2016 .

- Original voice recorder. (mp3; 216 kB) Airdisaster.com, archived from the original on December 26, 2011 ; accessed on August 12, 2016 .

- CVR transcript Japan Air Lines Flight 123 - 12 Aug 1985 . Aviation Safety Network , October 16, 2004, accessed August 12, 2016.

- Aircraft accident data and report in the Aviation Safety Network (English)

- Jumbo jet out of control (JAL 123) - Mayday - Alarm in the cockpit / episode 15. Spiegel TV , 2008, archived from the original on April 26, 2015 ; accessed on August 12, 2016 (video, 50 min).

- JAL123 Tokyo control communications records . Published on YouTube , August 12, 1985

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Jumbo jet out of control. ( Memento from April 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Video in: Spiegel TV , Mayday - Alarm im Cockpit , episode 15, 2008. (50 min)

- ^ Ed Magnuson: Last Minutes of JAL 123rd Time , p. 5, June 21, 2005, archived from the original on June 26, 2007 ; accessed on August 12, 2016 .

Coordinates: 36 ° 0 ′ 5 ″ N , 138 ° 41 ′ 38 ″ E