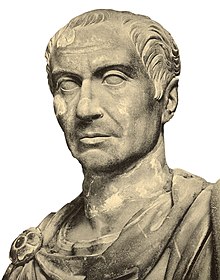

Calendar reform of Gaius Iulius Caesar

The calendar reform of Gaius Iulius Caesar , which began with the introduction of the Julian calendar in 45 BC. Was carried out, after which in the course of the Twelve Table Laws around 450 BC The change of the Roman calendar from a pure lunar calendar to a bound lunar calendar, which was decided in the 3rd century BC, was another profound change. The core of the Julian reform was the change from a bound lunar calendar to a solar calendar .

After the drastic measures in Caesar's day were almost completely ignored in daily practice, his calendar was not only fully accepted in the Roman Empire , but was later adopted in other empires and countries as well.

Calendar reform details

The first signs of a planned calendar reform are tangible after the death of Pompey , who fled to Egypt as an opponent of Caesar after his defeat in the battle of Pharsalus and there (according to the pre-Julian calendar) on September 28, 48 BC. BC ( 706 a. U. C. ) On behalf of the guardians of King Ptolemy XIII. was killed. Caesar followed Pompey to Egypt and could in Alexandria in the area late Hellenistic have been noted scholar on improvement of the existing Roman calendar system.

After his return in October 47 BC. The next important point was the prospect of a third term as consul in the center. Since contemporary sources for the background of the calendar reform in the political area are completely lacking, Caesar's motivation in this regard can only be interpreted in connection with other sources.

Caesar handed over the elaboration of the calendar reform to a committee, which consisted largely of non-Roman experts and was chaired by Sosigenes from Alexandria . Cassius Dio reports that Caesar first got to know the four-year switching rule in Alexandria . There are no indications of the participation of the pontifical college dominated by Caesar . The Senate received a notification, but did not take part in the resolution. The calendar reform was ordered orally, although the corresponding written edict was not issued until after Caesar's death in the second half of 44 BC. BC followed when the calendar reform had been in force for over a year and a half. Also largely orally, the distribution of the switching rule was later to be passed on; a broad-based writing on documents and disclosure to the public was omitted.

Caesar's new switching rule

Caesar chose a similarly cautious path for his calendar reform as he had already done in the course of the Decemvirs around 450 BC. Was trodden. The new switching rule said that an additional day should be added every fourth year in February and that the previous leap month Mensis intercalaris should be deleted without replacement. This corresponded to the same solution that Pharaoh Ptolemy III. 238 BC In the Canopus Decree for the ancient Egyptian calendar. The average year length was now 365.25 days.

The year 45 BC became the date when the new calendar reform came into force. Chr. (709 a. U. C.) Elected. When the new January 1st of the year 45 BC The first new moon after the winter solstice was arbitrarily defined, resulting in an additional 67 days for the year 46 BC. Chr. Required. A leap month of 23 days was already planned for this “ confused year ”, so it took a total of 355 + 23 + 67 = 445 days. This put the primary equinox on March 25th. More recent recalculations have shown that in 45 BC In reality the equinox took place on March 23rd and the new moon on January 2nd. With regard to the switching rule, Caesar used a formulation which, after his death, was interpreted in the traditional way by the priesthood responsible for switching according to the principle of " inclusive counting " and therefore led to a three-year switching. This is believed to be the oldest known example of a fence post failure .

The Roman law calculation of a period determined by days included the day of the event triggering the period as the first day of the period. The analogous application of this calculation rule to the determination of the leap years led to the wrong switching. The rule handed down by Macrobius nam cum oporteret diem qui ex quadrantibus confit quarto quoque anno confecto antequam quintus inciperet intercalare, illi quarto non peracto sed incipiente intercalabant stated that the placement had to take place after the performance (beginning) of the fourth year. However, since the last leap year was regarded as the first of the four counting years when determining the fourth year, the next leap year was incorrectly determined. Although the intention of Caesar's switching rule that a switching day should be inserted every "fourth year after the end of the last leap year" should actually have been clear to everyone involved, the (conservative) priesthood stuck to the traditional understanding of the switching instruction firmly. A corresponding correction was only made by Augustus by completely omitting a total of 3 leap days from the year 5 BC. Up to and including 4 AD.

Caesar's new daily distribution

There were ten days between the normal year of the Roman calendar, which comprised 355 days, and the adjustment to the 365-day ancient Egyptian system , which had to be inserted into the old structures. When allocating the days, Caesar had to take into account the interests of political and religious currents as far as possible, which is why he proceeded very carefully. The internal structures of the old months were not changed, nor were the existing months with 31 days and the 28-day February . In order not to change the cult character of the last day of the month as a conclusion, Caesar ordered the insertion of the additional one or two days after the penultimate day, so that there were only insignificant changes on the festive level. The days affected by the change are known from the Macrobius recordings :

“Dies autem decem, quos ab eo additos diximus, hac ordinatione distribuit: in Januarium et Sextilem et Decembrem binos dies inseruit, in Aprilem autem Iunium Septembrem Novembrem singulos: sed neque mensi Februaryio addidit diem, ne deum inferum religio inmutio Mautaretur, et Quintili inferum religio inmio Mautaretur Octobri servavit pristinum statum, quod satis pleno erant numero, id est dierum singulorum tricenorumque. "

| Change in the division of days over the months due to the Julian calendar reform | |||||||||||||

| year | Jan. | Feb | March | Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| old Roman calendar until 47 BC Chr. |

29 | 28 | 31 | 29 | 31 | 29 | 31 | 29 | 29 | 31 | 29 | 29 | 355 days |

|

Julian calendar from 45 BC Chr. |

31 | 28 | 31 | 30th | 31 | 30th | 31 | 31 | 30th | 31 | 30th | 31 | 365 days |

The assumption, expressed for the first time by Johannes de Sacrobosco without giving any sources, that the month of August had only 31 days since Emperor Augustus (like July), while February had 29 or 30 days respectively, could be based on the above passage from Macrobius and still much older text passages can be refuted.

Effects of the calendar reform

There are no contemporary sources available for the first posting as part of the calendar reform. Macrobius is likely to have referred to the reports by Suetonius , who with Cassius Dio was the earliest "documented historical witness" about a century and a half after the calendar reform, Suetonius probably having contemporary sources at his time, at the end of the first century AD. The statements of the chronograph of 354 are to be regarded as historically "worthless" , which combined its conclusions with the dates of the Varronic era and assumed fault-free switching from the beginning of the Julian calendar. The decision he made in reverse calculation that 45 BC BC represented the first leap year, suggests that the historical sources of Suetonius and Dio were not taken into account in this context, which would explain his lack of knowledge about the faulty circuits carried out up to Augustus . In addition, Cassius titled Dio 41 v. BC as an "unplanned leap year", which is why 45 BC BC after Dio could not have been a “planned leap year”.

The existing sources as well as Caesar's participation in the calendar reform make the first connection in 45 BC. Unlikely. Caesar scheduled a circuit for the last year of the four-year period. 45 BC However, it represented the following year of the four-year period that had ended before. It can therefore be assumed that the first scheduled switching after the calendar reform took place after Caesar's death (March 15, 44 BC). According to Macrobius, the unclear information from Caesar led to a three-year switching “within the next 36 years after the calendar reform, in which twelve instead of nine leap days were inserted”. But if 45 BC Should have been the first year of a four-year period, the first scheduled four-year cycle would have been 42 BC. BC or the first three-year circuit 43 BC. Must be done. However, this is in contradiction to the calendar intervention by Augustus, which occurred in the year 8 BC. BC apparently caused correction to the last switching in 9 BC. And omitted the next three leap years, which were for 5 BC. BC, 1 BC And 4 AD. It was not until 8 AD that Augustus set the usual four-year schedules again. With this, 45 v. Chr. As the first year of a regular four-year period, since Augustus would otherwise have caused the switching to continue from 7 AD. Based on the measures taken by Augustus, the reference point for the start of a four-year period is the year 44 BC. BC, which Caesar could have regarded as coinciding with the natural year and therefore in 44 BC. BC shortly before his death had a leap day added. Cassius Dio's explanations only make sense under this premise.

| Frequency of switching (S) in years (planned every 4 years = P; early every 3 years = V) | ||||||||||||

| circuit | S 1 | S 2 | S 3 | S 4 | S 5 | S 6 | S 7 | S 8 | S 9 | S 10 | S 11 | S 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 years (P) | 41 BC Chr. | 37 BC Chr. | 33 BC Chr. | 29 BC Chr. | 25 BC Chr. | 21 BC Chr. | 17 BC Chr. | 13 BC Chr. | 9 v. Chr. | 5 v. Chr. | 1 v. Chr. | 4 AD |

| 3 years (V) | 42 BC Chr. | 39 BC Chr. | 36 BC Chr. | 33 BC Chr. | 30 BC Chr. | 27 BC Chr. | 24 BC Chr. | 21 BC Chr. | 18 BC Chr. | 15 BC Chr. | 12 BC Chr. | 9 v. Chr. |

Cassius Dio's account shows that in the Julian calendar in February 41 BC The unscheduled leap year is said to have been inserted to "prevent the coincidence of January 1st with a market day (nundinae / merkatus) ". In addition, there is the striking finding that the nuns in the Roman Republic in the months Martius to December carry all other nouns except the "G" ("A, B, C, D, E, F and H"). The assumption expressed that simultaneity with the "G" was prevented by a leap day is not borne out by current switching practice. In order to prevent the assignment with the "G", the placement should have taken place in February; this would have made “G” a “D” at the turn of the year. Another three-day circuit should have been made next February to prevent the collapse again.

The reference made in this way to the market day represented an impossible procedure on the basis of the fixed Julian calendar switching scheme, which is why the mention of Cassius Dio actually does not start with the year 41 BC. Is to be reconciled, since without switching on January 1, 40 BC. The market letter "A" would have followed. The occurrence of a leap day attested by Cassius Dio is at the same time the only evidence of a leap month in connection with the calendar reform in the immediate vicinity of Caesar. There is therefore the possibility that it was an additional incorrect interpretation of the switching rule formulated by Caesar.

swell

- Pliny the Elder : Naturalis Historia : 18, 211-212.

- Suetonius : Divus Iulius : 40

- Plutarch : Caesar : 59

- Censorinus : de The natali Liber : 20.6-11.

- Cassius Dio : Roman History : Vol. 43, 26.

- Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius : Saturnalia : Vol. 1, 14

literature

- Wilhelm Drumann, Paul Groebe: The Roman calendar in the years 64-43 BC. Chr. In: Wilhelm Drumann, Paul Groebe: History of Rome in its transition from the republican to the monarchical constitution, or: Pompejus, Caesar, Cicero and their contemporaries, Vol. 3: Domitii - Julii . Bornträger Brothers, Leipzig 1906.

- Jürgen Malitz: Caesar's calendar reform. A contribution to the history of his later period . In: Ancient Society . Vol. 18. Universitas Catholica Lovaniensis, Leuven 1987, pp. 103-131 ( online version , PDF ).

- Theodor Mommsen : Chronica minora saec. IV, V, VI, VII . 3 volumes. Weidmannsche Verlagbuchhandlung, Berlin 1892–1898. Reprinted Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Munich 1981.

- Jörg Rüpke : Time and Feast: A Cultural History of the Calendar . Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54218-2

- Jörg Rüpke: Calendar and Public: The History of Representation and Religious Qualification of Time in Rome . de Gruyter, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-11-014514-6 .

- Ekkehart Syska: Studies on theology in the first book of Saturnalia by Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius . Teubner, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-519-07493-1 .

Web links

- Naturalis historia , original Latin text in its entirety, partially edited by LacusCurtius

- en The natali Liber , Latin text of the edition of Cholodniak (French translation) by LacusCurtius

- Roman History , Vol. 43

- Ambrosius Theodosius Macrobius: Saturnalia , French translation .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Date of the Roman calendar.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 43:26.

- ↑ a b c d Jörg Rüpke: Calendar and Public: The History of Representation and Religious Qualification of Time in Rome . Pp. 585-587.

- ^ Jürgen Malitz: Caesar's calendar reform. A contribution to the history of his later period. In: Ancient Society , 18, 1987, pp. 103-131.

- ^ Herbert Metz: The Julian calendar . computus.de

- ^ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1, 14, 13.

- ↑ Jörg Rüpke: Time and Feast: A cultural history of the calendar . P. 33.

- ^ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1, 14, 7.

- ↑ Sacha Stern: Calendars in Antiquity . Oxford University Press, 2012. Note 155 at p. 212.

- ^ Jürgen Malitz: Caesar's calendar reform. P. 120.

- ^ A b Jörg Rüpke: Calendar and Public: The History of Representation and Religious Qualification of Time in Rome . P. 382.

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalien 1,14,13-15: Sic annum civilem Caesar habitis ad lunam dimensionibus constitutum edicto palam posito publicavit. Et error hucusque stare potuisset, ni sacerdotes sibi errorem novum ex ipsa emendatione fecissent. Nam cum oporteret diem qui ex quadrantibus confit quarto quoque anno confecto, antequam quintus inciperet, intercalare: illi quarto non peracto sed incipiente intercalabant. (14) Hic error sex et triginta annis permansit: quibus annis intercalati sunt dies duodecim, cum debuerint intercalari novem. Sed hunc quoque errorem sero deprehensum correxit Augustus, qui annos duodecim sine intercalari die transigi iussit, ut illi tres dies qui per annos triginta et sex vitio sacerdotalis festinationis excreverant sequentibus annis duodecim nullo die intercalato devorarentur. (15) Post hoc unum diem secundum ordinationem Caesaris quinto quoque incipiente anno intercalari ussit, et omnem hunc ordinem aereae tabulae ad aeternam custodiam incisione mandavit.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History 48,33,4.

- ↑ Under this premise, the preceding market letters for January 1st are: 43 v. Chr. "H", 42 BC BC "C" and 41 BC Chr. "F". However, this combination does not lead to a collision.