Clothes louse

| Clothes louse | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clothes lice when mating |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Pediculus humanus humanus | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

The body louse ( Pediculus humanus humanus ) and body louse ( Pediculus humanus corporis called), is an on the people of specialized blood-sucking ectoparasite ( pediculosis ) and often carriers of pathogens .

features

The clothes louse is about 4 mm in size and colored whitish to brown. The female can live up to 40 days, laying around ten eggs per day. The development to the adult animal takes two weeks at best.

Clothes lice are particularly well adapted to humans and can not tolerate the blood of other mammals . Completely sterilized, the louse could not survive, because it is not capable of the vital for them Vitamin B5 prepare itself which it by the bacterium Candidatus Riesia is supplied symbiotically alive in the body louse. On the other hand, clothes lice are very tough and can survive for up to four days at 25 ° C without food.

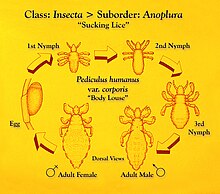

As with other hemimetabolic insects, there is no complete metamorphosis ; rather, the nymphs of the clothes louse largely correspond to the adult animals.

The genome of the clothes louse contained in six chromosomes was sequenced in 2010 by a multinational team . A total of 10,773 genes were identified, making the clothes louse the smallest known insect genome to date . According to the researchers, this genome size reflects the parasite's limited habitat and easy diet. In genome research, only a few genes were identified that cause light sensitivity, which is why the eyesight of the clothing louse is severely restricted. In addition, it does not have many genes for odor perception and also has the smallest number of detoxifying enzymes in the insect world that can be used to render food harmless.

parasite

The clothes louse is an ectoparasite exclusively of humans and lives preferentially in the body hair, both on the head and all other body hair, and finally in the clothing. In contrast to head and pubic lice, the inhabited areas of hair do not itch. From there, however, it embarks on a journey to adjacent exposed areas of skin, so that it stings in the arms and legs like a flea. The clothes lice on the hair of the head attack the auricles, but also the forehead, neck and cheeks. It is well adapted to people and feels most comfortable at human body temperature. The stings of the louse usually trigger a small, itchy swelling. The louse is transmitted through body contact, shared bedding or clothing.

Coevolution

The body louse presumably emerged from the head louse - its prehistoric appearance roughly marks the point in time from which humans regularly wore clothes ( coevolution ). Genetic analyzes indicated that the origin was about 72,000 ± 42,000 years ago and the origin was Africa . Human ancestors were infested with the ancestors of the head and clothing lice around 5.5 million years ago, the time when the lines of development of chimpanzees and humans separated.

Taxonomy

The clothes louse is mostly understood as a subspecies of the human louse ( Pediculus humanus ), a type of animal lice . The head louse ( Pediculus humanus capitis ) is another subspecies of the human louse . However, it has not been conclusively clarified whether there are actually two subspecies or whether the body louse and head louse represent two different species . An older name for the clothing louse was Pediculus vestimentorum .

Disease transmission

Under poor hygienic conditions, the body louse can anywhere, but especially in the tropics , both bacterial typhus ( typhus , lice fever ) ( Rickettsia prowazekii ) and the bacterial lice relapsing fever (pathogen: different Borrelia among other Borrelia recurrentis ), tularemia ( Pathogen: Bacterium Francisella tularensis ) and Volhynian fever ( Bartonella quintana ) transmitted to humans. The transmission does not take place through the bite itself, but through contact infection or smear infection with the excrement of the louse or through crushed animals, especially if they get into the bite wound or other skin wounds.

In earlier times there were real epidemics of these diseases, especially in areas with poor hygiene and heavy lice infestation, today they are particularly common in the cooler areas of Africa, South America and Asia. These diseases are characterized by strong attacks of fever.

A group of researchers at the University of Marseille led by Didier Raoult is of the opinion that if the host changes, the clothes louse, in addition to the head louse and the human flea ( Pulex irritans ), can be considered as vectors of the plague , as all of these parasites can ingest plague bacteria.

According to the Infection Protection Act, clothing lice infestation must be reported to the health department in Germany .

Clothing louse control

The most important method of combating it is therefore to treat all parts of the hair with physically active substances from the pharmacy and at the same time wash all items of clothing at at least 60 °. If some items of clothing cannot tolerate high temperatures, the only way to starve the lice is to collect these items in a bag for at least 14 days. At the same time, you have to thoroughly clean the rooms and finally treat them with a vermin fogger from the pet store. Public transportation is the main place of transmission. There you should not only avoid body contact, but also keep your head away from the headrests on trains and coaches. The best way to do this is to use a neck pillow. Of course, general hygiene must be observed. This means general personal hygiene and regular changing and cleaning of clothes, as the clothes louse is also transmitted with them.

The bacterium Candidatus Riesia is an essential endosymbiont for the clothes lice , but at the same time it opens up a starting point for a possible antibacterial defense against clothes lice. Since the genome of this bacterium does not contain any resistance genes according to previous knowledge , it could therefore be killed by antibiotics , which would result in the later death of the clothing louse.

Importance for research

The manageability of the clothing lusgenome and the fact that this animal has an extremely small number of food-detoxifying enzymes make it the ideal test organism for scientific research into insect resistance to insecticides .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Ralf Kittler, Manfred Kayser, Mark Stoneking: Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus and the origin of clothing. In: Current Biology , Volume 13, No. 16, 2003, pp. 1414-1417. doi : 10.1016 / S0960-9822 (03) 00507-4 .

- ↑ a b Christine J. Ko, Dirk M. Elston: Pediculosis. In: Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology , Volume 50, No. 1, 2004, pp. 1-12. doi : 10.1016 / S0190-9622 (03) 02729-4 .

- ↑ a b c d Body louse dependent on foreign genes ( Memento of the original from April 17, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Deutsches Ärzteblatt, June 22, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Lousy genome. The genetic make-up of the blood-sucking clothes louse, which transmits dangerous diseases to humans, has been deciphered. On: Wissenschaft.de from June 22, 2010.

- ↑ a b E. F. Kirkness, BJ Haas, W. Sun et al. : Genome sequences of the human body louse and its primary endosymbiont provide insights into the permanent parasitic lifestyle . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences ( PNAS ) . 107, No. 27, July 2010, pp. 12168-73. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1003379107 . PMID 20566863 . PMC 2901460 (free full text).

- ↑ Genome of the clothes louse .

- ↑ Proteome at UniProt .

- ↑ David L Reed, Jessica E Light, Julie M Allen, Jeremy J Kirchman: Pair of lice lost or parasites regained: the evolutionary history of anthropoid primate lice. In: BMC Biology. Volume 5, No. 7, 2007. doi : 10.1186 / 1741-7007-5-7 ( full text online ).

- ↑ Melissa A. Toups, Andrew Kitchen, Jessica E. Light, David L. Reed: Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa. In: Molecular Biology and Evolution. Volume 28, No. 1, 2011, pp. 29-32, doi : 10.1093 / molbev / msq234 , ( full text online ).

- ↑ a b c Jessica E. Light, Melissa A. Toups, David L. Reed. What's in a name: The taxonomic status of human head and body lice. (PDF) In: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution , Volume 47, No. 3, 2008, pp. 1203-1216.