Endometrial cancer

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| C54.1 | Malignant neoplasm of the corpus uteri: endometrium |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The endometrial carcinoma , also uterine or body carcinoma ( lat. Carcinoma corporis uteri ) is a cancer of the uterine lining .

histology

Histologically , 85% of the cases are adenocarcinomas of the uterine lining (endometrium) . Rare types are e.g. B. serous and clear cell adenocarcinomas or squamous cell carcinomas . The degree of dedifferentiation (degeneration) of the cancer cells is given as G1 (highly differentiated, very similar to normal tissue) to G3. Many carcinomas express estrogen and progesterone receptor molecules on the cell surface .

Staging

The classification of the FIGO and that of the UICC are identical; they are based on the TNM system , as with other solid cancers .

- Example: Stage IA (FIGO) = T1a (UICC) = tumor limited to the mucous membrane.

The chances of recovery depend on it: for example 90% in stage IA, 30% in stage III. Undifferentiated tumors are more difficult to heal than highly differentiated ones.

Stages according to TNM classification and FIGO (Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique):

| TNM | FIGO | criteria |

|---|---|---|

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of a primary tumor | |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ | |

| T1 | I. | Tumor limited to the body of the uterus |

| 1a | IA | Tumor confined to the endometrium or infiltrates less than half of the myometrium |

| 1b | IB | Tumor infiltrates half or more of the myometrium |

| T2 | II | Tumor infiltrates the stroma of the cervix uteri, but does not spread beyond the uterus |

| T3 and / or N1 | III | local and / or regional spread |

| 3a | IIIA | Tumor affects the serosa of the corpus uteri and / or the adnexa (direct spread or metastases) |

| 3b | IIIB | Vaginal involvement and / or involvement of the parametria (direct spread or metastases) |

| 3c or N1 | IIIC | Metastases in pelvic and / or para-aortic lymph nodes |

| 3c1 | IIIC1 | Metastases in pelvic lymph nodes |

| 3c2 | IIIC2 | Metastases in para-aortic lymph nodes with / without metastases in pelvic lymph nodes |

| T4 | IV | Tumor infiltrates the bladder and / or intestinal mucosa |

| Nx | No statement can be made on regional lymph node metastases . | |

| N0 | No metastases in the regional lymph nodes. | |

| N1 | Metastases in the regional lymph nodes. | |

| M0 | No distant metastases detectable. | |

| M1 | The tumor has formed distant metastases. (except vagina, pelvic serosa, adnexa; including inguinal and abdominal lymph nodes other than para-aortic and / or pelvic lymph nodes) |

Preliminary stages and early forms

Endometrial hyperplasia without atypia is a benign disease that only requires treatment if there are symptoms (e.g. persistent bleeding). These mucosal changes are caused by persistent hyperestrogenism , especially in postmenopausal , very overweight women. Only about 1% of patients later develop endometrial cancer. In the case of endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, on the other hand, up to 30% of women have an invasive endometrial cancer in the further course. Women who have experienced a finding of endometrial hyperplasia with atypia in the curettage a hysterectomy was performed, Danish researchers of the preparations found in 59% invasive endometrial cancer, in 82% FIGO stage I. For this reason, recommends the S3 guideline endometrial cancer in all women with endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, a hysterectomy if there is no longer any desire to have children . Endometrial hyperplasia with atypia predominantly results in type I carcinomas, namely endometroid and mucinous carcinomas with a good prognosis. Molecularly, these tumors are characterized by mutations of PTEN , K- RAS , beta- catenin and changes in the mismatch repair system .

After the dualistic model for the pathogenesis of the endometrium according to Bokhman, there is a second way to the formation of endometrial cancer. These so-called type II carcinomas arise on the floor of an atrophic endometrium or within glandular-cystic endometrial polyps. Type II carcinomas also include serous and clear cell carcinomas, which have an unfavorable prognosis. Molecularly, a mutation of TP53 , an overexpression of cyclin E and changes in the PIK3CA pathway can be found.

Occurrence

The incidence of endometrial cancer is highest in North America and Western Europe, with 9.9 to 15 new cases per 100,000 women per year. The USA has the highest incidence rate. Here 1.7% of women fall ill up to the age of 75. In Germany, more than 11,000 new diagnoses were made in 2002. The incidence rate per year has risen in recent years and is currently 25: 100,000 women. It mainly affects (approx. 66–85% depending on the source) women who have climacteric after menopause . 5% are younger than 40. The incidence in western countries is about twice that of cervical cancer .

causes

It is assumed that long-term increased estrogen concentrations promote tumor development; z. For example, women with menstrual disorders, later menopause or hormone replacement therapy have a higher risk than the population average. The lifestyle diseases overweight, high blood pressure and diabetes mellitus II increase the risk of tumors. It is known that obesity increases the production of estrogen. It has not yet been clarified whether there is a risk from phytoestrogens (estrogen-like substances in food). What is certain, however, is that hormone therapy exclusively with estrogens increases the risk.

Causes of hereditary susceptibility to endometrial cancer include mutations in genes that code for DNA mismatch repair proteins .

Symptoms and diagnosis

Early cancers can rarely be detected during early detection examinations. Instead, the tumor becomes noticeable early on through bleeding. Bleeding after the onset of menopause is therefore always suspect, as are irregular bleeding and discharge the color of flesh. 75% of all endometrial cancers are found in the first stage. The 5-year survival rate is then 90%. Abdominal pain almost always signifies an advanced, inoperable tumor. The diagnosis is confirmed by scraping the uterus ( abrasio uteri ).

In recent years, 3-D sonography has improved the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. The volume measurement and the three-dimensional representation make it possible, on the one hand, to precisely identify the carcinoma and, on the other hand, to record the benign changes. This avoids unnecessary interventions in the form of curettages . Currently, around half of all curettages can be avoided.

treatment

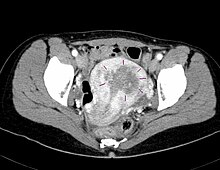

Whenever possible, corpus carcinomas should be surgically removed. The standard operation is performed by means of a longitudinal incision in the lower abdomen or a laparoscopy and includes at least one total uterine removal and the removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes on both sides. Depending on the stage, among other things, the removal of at least the half of the uterine connective tissue near the uterus , the removal of a vaginal cuff , the exposure of both ureters and the removal of lymph nodes in the small pelvis (pelvic lymphadenectomy ) and along the abdominal aorta up to the exit of the renal arteries (para-aortic lymphadenectomy) may also be required (radical hysterectomy according to Piver II / III or Wertheim-Meigs operation ). Higher stages should receive radiation therapy afterwards . Inoperable tumors are only irradiated. For serous papillary and clear cell endometrial cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy has recently been used.

forecast

The prognosis of the most common type, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, is relatively good with a mortality rate , i.e. the risk of dying from the disease, of 6%. For the other species, lethality varies between 21% and 51%. As with all tumors, a lack of differentiation of the cells also worsens, i. H. a major change in the original gland cells that made the prognosis. On average, 80% of those affected survive five years after diagnosis. In stage I it is even 90%, in stage II 83%, in stage III 43%. After two years, a relapse, i.e. renewed growth of tumor cells, becomes unlikely. However, there is still an increased risk of developing breast cancer for the rest of life.

See also

Web links

- S2 guideline : Endometrial cancer , AWMF register number 032/034 (full text) , as of 12/2010

- Dissertation on the topic. (PDF; 6.1 MB)

literature

- Klaus Diedrich , Wolfgang Holzgreve, Walter Jonat , Askan Schultze-Mosgau, Klaus-Theo M. Schneider: Gynecology and Obstetrics . Springer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-540-32867-X ( full text in the Google book search).

- Dominik Denschlag, Uwe Ulrich, Günter Emons: Diagnosis and therapy of endometrial cancer: progress and controversy . In: Dtsch Arztebl Int . No. 108 (34-35) , 2011, pp. 571-577 ( review ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ L.-C. Horn, K. Schierle, D. Schmidt, U. Ulrich: New TNM / FIGO staging system for cervical and endometrial carcinoma as well as malignant Müllerian mixed tumors (MMMT) of the uterus. In: obstetric women's health. 69, 2009, pp. 1078-1081, doi: 10.1055 / s-0029-1240644

- ↑ L.-C. Horn, K. Schierle, D. Schmidt, U. Ulrich, A. Liebmann, C. Wittekind: Updated TNM / FIGO staging system for cervical and endometrial carcinoma and malignant mixed tumors (MMMT) of the uterus. Facts and background. In: Pathologist. 2011, PMID 20084383

- ↑ Staging of endometrial cancer since 2010 in the new guideline for diagnosis and treatment of endometrial cancer published by the AGO (Gynecological Oncology Working Group)

- ↑ R Zaino, SG Garinelli, LH Ellenson: tumor of the uterine corpus: epithelial Tumors and precursor. In: CM Kurmann, CS Harrington, Joung RH (Eds.): WHO Classification of Tumors of the Female Reproductive Tract . IARC Press, Lyon, 2014, pp. 125-126 (English).

- ↑ Sofie Leisby Antonsen, Lian Ulrich, Claus Høgdall: Patients with atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium Should be Treated in oncological centers . In: Gynecologic Oncology . tape 125 , no. 1 , 2012, ISSN 1095-6859 , p. 124-128 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ygyno.2011.12.436 , PMID 22198048 .

- ↑ a b Oncology Guideline Program (Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Diagnostics, Therapy and Follow-Up Care for Patients with Endometrial Cancer, long version 1.0, 2018. 2018, accessed on July 26, 2019 .

- ↑ X Matias-Guiu, L Catasus, E Bussaglia, H Lagarda, A Garcia: Molecular pathology of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma . In: Human Pathology . tape 32 , no. 6 , 2001, ISSN 0046-8177 , p. 569-577 , doi : 10.1053 / hupa.2001.25929 , PMID 11431710 .

- ↑ JV Bokhman: Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma . In: Gynecologic Oncology . tape 15 , no. 1 , 1983, ISSN 0090-8258 , pp. 10-17 , PMID 6822361 .

- ↑ K. Diedrich among others: Gynecology and obstetrics. 2nd Edition. Springer Verlag, 2007, p. 240.

- ↑ a b K. A. Nicolaije et al .: Follow-up practice in endometrial cancer and the association with patient and hospital characteristics: A study from the population-based PROFILES registry. In: Gynecologic Oncology . 129 (2), 2013, pp. 324-331, PMID 23435365

- ↑ C. Yaman, A. Habelsberger, G. Tews, W. Pölz, T. Ebner: The role of three-dimensional volume measurement in diagnosing endometrial cancer in patients with postmenopausal bleeding. In: Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Sep; 110 (3), pp. 390-395. doi: 10.1016 / j.ygyno.2008.04.029 . Epub 2008 Jun 24.