Rheinberg prisoner of war camp

Coordinates: 51 ° 32 ′ 32.3 " N , 6 ° 34 ′ 53.7" E

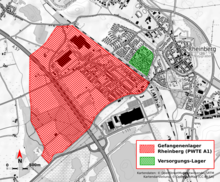

The POW camp Rheinberg was the first of the Allies built Rheinwiesenlager . It served as a transit camp for prisoners of war who were arrested by the American shock wedge on their way from the Wesel bridgehead to the Elbe. It was erected around April 14, 1945 by soldiers of the 106th US Infantry Division using German prisoners of war. For this purpose, west of Rheinberg, along the current Duisburg – Xanten railway line, a 350-hectare arable and meadow area was surrounded by three-meter-high barbed wire fences and hermetically sealed off from the outside world.

It was divided into eight individual camps, called cages , without any housing, sanitary facilities or even supply structure. More than 130,000 prisoners of war are crammed into it, 8,000–30,000 per cage. Cold, hunger, poor hygiene and a lack of medical care were the main causes of serious illnesses. The number of deceased prisoners of war within the camp is estimated at 3,000–5,000.

From mid-June 1945 it was handed over to a British unit. It existed until September 1945.

The POW camp PWTE A1

The official American name of the camp was "Prisoners of War Temporary Enclosure A1" (PWTE A1). The expanse of the camp was enormous. In an east-west direction, it extended from the railway line to shortly before the Heydecker Ley, roughly at the level of the Rheinberg War Cemetery and the Haus Heideberg estate. In the north it was bordered by the Alpener Straße (K 31) and in the south by today's B 510. Rheinberg was then a small town with just under 5,400 inhabitants. In March 1945 the Allies evacuated them to the surrounding communities during the fighting and began to build the camp by confiscating fertile farmland. It was not until April that the residents were allowed to return to their destroyed and looted hometown and start rebuilding. The 3,000-strong occupation force also had to be supplied.

PWTE A1 was led by a single-star general from the 106th US Infantry Division. During the Battle of the Bulge , the unit suffered heavy losses from the German soldiers. Now she was used to guard the Rhine meadow camp. Not only Wehrmacht members from the Rhineland came to the camp . Rather, Rheinberg was the target of all prisoners and those picked up from the US shock wedge, which from there, widening and widening, extended over Wesel, Duisburg, the northern Ruhr area, East Westphalia, the Lipperland, the Harz to the Elbe. They were transported to the farmland from all captured areas of Germany by trucks and freight trains. The Allies made no distinction whether the prisoners were soldiers, forced laborers, seriously injured, civilians, men, women or children. Anyone wearing some kind of uniform was arrested, including nurses, railroad workers and postmen. Their number quickly grew to over 70,000 between the ages of 7 and 80.

Registration did not take place in the first few weeks. The prisoners were only roughly separated into men, women and non-Germans and distributed among the various cages. The only thing that was taken care of was that commanders did not meet with their units as the Americans feared the formation of organized resistance groups. Upon arrival, the prisoners were thoroughly searched and everything that was of value or could be used as a weapon was confiscated, so that many only had clothes on. In the course of this, they were even stripped of their prisoner-of-war status. As " Disarmed Enemy Forces " ( Disarmed Enemy Forces ) they fell out of both the Geneva Conventions and the Hague Land Warfare Regulations . International aid organizations had no access due to this regulation. Completely disenfranchised, the prisoners were at the mercy of the American soldiers for better or for worse.

There was no accommodation. In order to protect themselves from wind and weather, the imprisoned dug caves and holes in the ground, in which they spent the night in small groups as an emergency community. It is not uncommon for these badger burrows to collapse or to fill up with water when the weather persists. Only the women in Cage B were allowed a few tents, which served more as a privacy screen than to ward off rain and cold. The food rations were reduced to an obligatory “knife tip catering”, were distributed at irregular times and on some days were completely canceled. The drinking water was supplied by tank trucks . For a small can of strongly chlorinated river water, some of the prisoners had to queue for over 16 hours. Dug pits with thunder bars served as toilets, and DDT powder was used to combat lice . There were no washing facilities. The consequences of a lack of medical care, poor hygiene and insufficient food were the main causes of infections, diseases and malnutrition.

Attempts to flee were prevented by force of arms and those who dared to do so were shot or shot by the American soldiers. Some shootings were also carried out as an act of revenge for a fallen comrade or because of the German hatred propagated in America. For the occupiers there was an absolute ban on fraterization with the Germans in order to maintain the image of the enemy . Despite constant harassment, the prisoners were forced to come to terms with the soldiers more or less voluntarily. Occasionally there were barter deals between them, as wristwatches , Nazi military badges and self-made works of art were very popular with the soldiers as souvenirs . Nevertheless, one did not trust the Germans on the way. In the cages, there was also a very tense relationship with each other due to the dull camp and constant hunger. Within a comradeship, one made the most embarrassing attention to the fact that a few small snacks were distributed fairly. It happened among the individual groups that the prisoners stole from each other or fledddtddorbe corpses in order to e.g. B. to secure one's own survival with a coat. Due to physical and mental overload , some people got a camp fever .

Since the German Red Cross was temporarily banned by the Allies as an aid organization with NSDAP connection, the population of Rheinberg and the surrounding area tried to support the starving prisoners with bread packets, which they threw over the fence. Messages were also sent to relatives on paper, as otherwise there was no contact with the outside world. The donors put themselves at great risk of being killed and the message did not always reach the recipient. Sometimes the parcels got stuck in the barbed wire fence, were crumbled in the fight for that little bit of food or fell into the patrol corridors. Depending on which guard was on duty, the parcels were trodden down in front of the starving people or distributed to the prisoners from the watchtower as "predatory animal feed".

With the capitulation , the registration of the prisoners gradually began from around mid-May 1945 in order to obtain a general overview of their number. A supply warehouse was set up on a piece of land east of the train station. Here the arranged food aid and donations should be accepted and the distribution should be brought into an orderly process. Tents were set up for a prison hospital and the 9th American field hospital in Kamp-Lintfort was opened for the medical treatment of German soldiers. German doctors and nurses from the camp were used as medical personnel to support the Americans. Inmates were also recruited for the distribution of food and as auxiliary police officers within the camp. Compared to the other prisoners, the auxiliaries received some privileges and tents as accommodation, so that a prisoner hierarchy was formed. The background to this was a visit to the camp by an international Red Cross commission at the end of April. As part of this, young people and members of certain professional groups who were necessary for the establishment of a functioning supply economy, such as farmers, railway workers, truck drivers and miners, were released.

But soon the old routine prevailed again. Thanks to German assistants who were recruited for the supply, the distribution of food was more regulated, but it was still limited to the minimum. For the most part, health care continued to consist of good reception, as there was often a lack of surgical tools, medication and bandages, and delousing with DDT. Most of the prisoners continued to live in holes in the ground. It was not uncommon for deployed assistants to benefit from their position and thus to envy themselves. If someone was caught stealing or any other offense, draconian punishment threatened. Not only by the American guards, but above all by the inmates themselves. Being tied to a stake was relatively harmless. It also happened that the culprit was drowned in the latrine .

Conditions in the Rheinberg POW camp only improved when the British military government took over the camp on June 12, 1945 . British Commander Officer Colonel Tom Durrant was in charge of this. He knew Germany from his student days and had visited the country several times before the war. After seeing the desolate condition in which the Americans left the huge camp after their departure and he learned that the more than 100,000 prisoners, including women and uniformed civilians, had been living in the field for months without any accommodation, he contacted the AGRA -Headquater in connection. Tents were requested, drilled for water and pipelines with diesel pumps were laid for a secure supply, field kitchens were built and the field hospital was rebuilt. The seriously ill and wounded were distributed to the surrounding functioning hospitals. The prisoners were also allowed to shower once a week and to clean their clothes.

The British military then began to structure the warehouse operations. A British officer was in charge of managing the cages. Does it support was of various Non-Commissioned Officers (NCO = sergeant ) and an English-speaking German senior officer. Inside the cages, a German confidential officer, assisted by a number of NCOs, maintained communication between the British camp management or its staff and the prisoners. Since the British were primarily concerned with tracking down Nazi officials and war criminals in hiding, the prisoners were encouraged to name them, which was quite promising. Numerous Nazi people found were transferred to the internment camp in Weeze and, among other things, brought to the Belgian coal mines as forced laborers or sent to the field to clear mines.

Shortly after the takeover, Durrant ordered the release of innocent prisoners of war from whom there was no danger. Women, children, the elderly, as well as “uniformed civilians” such as postmen and railway employees were released within the first week. As a result, the British military administration was able to drastically reduce the expenditure for the camp overall and wanted to save on food and medicine in particular. As this made it impossible to adequately care for the prisoners within the framework of the Geneva Conventions and thus also endangered the lives of their own soldiers due to emerging epidemics, Durrant wrote a critical status report. In addition, he arranged for the ban on fraterization to be lifted. Shortly afterwards, on June 14, 1945, the Büderich (Wesel) camp was closed and 30,000 remaining prisoners of war who did not come from construction professions or who could be moved to the French and Belgians as forced laborers were relocated on foot to the Rheinberg camp.

Due to the high number of prisoners, the British were also afraid of a camp revolt, as the unit would be far inferior in an uprising. To prevent this, it was made clear to the inmates that the western allies were serving as a protective force against the Russians and that they would not end up in the gulag . Furthermore, with the help of the prisoners from the officers' cage, cultural and training events were organized for the prisoners of war. In these "barbed wire universities" they passed on their diverse qualifications and interests, and many people learned a musical instrument in addition to the English language or received professional training. Paper and writing materials were requested from the commander, musical instruments were donated by private individuals. Despite the privileges granted, the prisoners were basically only forced laborers who paid off the war costs incurred for the British in the form of natural resources and agricultural products.

As autumn approached and the British military administration did not want to build winter-proof accommodations for the many thousands of prisoners, the internees were released from September 1945 or redistributed to French camps. Shortly after the dissolution, it was leveled to make room for agricultural land.

Ground monument

The as yet undeveloped area of the former Rhine meadow camp Rheinberg is now designated as a ground monument . The main camp in today's Rheinberg district of Annaberg, however, has been almost completely built over by settlement area since the 1960s to 1970s. The rest is a protected landscape area and is used for agriculture.

In 2002 and 2003 the opportunity arose to archaeologically examine and record a small part of the ground monument. The reason for this was the construction of a bypass road and a warehouse. In addition to the time pressure and the large number of copies, a difficulty was that the information on the size of the camp and its distribution are very contradictory despite reports from contemporary witnesses; there are no official information or documents. So you didn't know exactly which part of the Rhine meadow camp you were in. The yield of finds and results was relatively low. Post pits, barbed wire and metal remains, pits and fireplaces scattered across the area, as well as a few glass and ceramic shards, metal and plastic fragments, utensils and bones from the time of the camp and afterwards were found.

The Rheinberg City Archives are showing some of these finds on guided tours. Others can be found in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn or are documented at the State Office for Land Monument Preservation .

Places of remembrance

In Rheinberg, several memorials commemorate the Rhine meadow camp and the many thousands of victims of captivity. The Rheinwiesenlager memorial stone is located directly at the Annaberg municipal cemetery, on a green area in front of the morgue. The boulder is part of a memorial with flagpoles and reminds of the former location of the camp in 1945. A small information board in front of it briefly describes the historical background. Originally a larger version was planned by the Heimatverein, which should be on the roundabout on Römerstrasse. Due to protests from the population and cost reasons, an agreement was made on the smaller version and another place.

Not far away, in the new part of the cemetery, there is a tall, white cemetery cross in the form of a memorial stele with a sun wheel. A barbed wire pattern is carved around its frieze, as a symbol for the camp and in memory of the many nameless and unknown buried. It was made in 2007 by the Rheinberg stonemason Dieter Knop. Both the Catholic and Protestant congregations took over the financing. It was inaugurated at an ecumenical service.

Another place where the memory of the Rheinwiesenlager is kept alive is in the middle of the old town of Rheinberg. In the parish church of St. Peter there is a church window that is reminiscent of the Rhine meadow camp. It is located in the right aisle near the entrance and looks a little faded, although it was only re-installed in March 1990. Are shown Cardinal von Galen and Karl Leiser with a roll of barbed wire and Jesus on the cross to the foot of a sacrificial bowl is in someone washes his hands. Under the roll of barbed wire it says: "Here too we commemorate the victims of the Rheinberg prison camp".

The Gate of the Dead is probably the most famous memorial for the victims of the wars in Rheinberg. It's right behind St. Peter on the Kettewall. Due to the name, its location directly on the Rhine meadows and a roll of parchment that is in a concrete block behind the memorial plaque, the place of remembrance is often associated with the Rhine meadow camp. But this is not the case. It is a memorial for the victims of the wars in Rheinberg. Anyone who previously believed that the names of the victims of the prisoner-of-war camp were on the parchment will be disappointed. According to the archives, it contains the 650 names of Rheinberg citizens who died or disappeared during the war years. The people from the Rhine meadow camp are not mentioned.

Others

Merrit Peter Drucker, an American major who was stationed in the former Reichel barracks at the end of the 1980s , came across the Rheinwiesenlager memorial stone at the Annaberg cemetery while walking. Since nothing was known about the Rhine meadow camps in the USA, he became curious and began to research. He met contemporary witnesses and former camp inmates. Horrified by the dark events in his country's history, on July 11, 2011, he published an “Open letter to former German prisoners of war in camps of the US Army”, which at the end of 2011 was printed full-page in Focus . The following year he organized a memorial service at the memorial to personally apologize to the victims and survivors. In addition, a meeting with international military personnel and historical researchers was arranged, in which, among others, the Canadian publicist James Bacque took part. Not all invited guests showed up. Despite their good will and the honorable deed, representatives of the parishes and the mayor feared a loss of image and did not want to be lumped together with neo-Nazis and historical revisionists who might have traveled. The Rhine meadow camps are still a taboo subject today.

Note on the sources

Only a few archive sources and contemporary witness reports exist today about the Rheinwiesenlager in Rheinberg. Since the Allies did not leave any official documents, the dates, prisoner and death figures vary widely.

literature

- Sabine Sweetsir: The Rheinberg prisoner of war camp in 1945. Contemporary witnesses testify. A documentation. Stadt Rheinberg - Stadtarchiv, 4th edition 1998

- City Archives Rheinberg: Administrative report of the city of Rheinberg 1945–1955.

- Rüdiger Gollnick: Foreign in enemy country - foreign in home country. Searching for traces on the Lower Rhine. Pagina Verlag GmbH Goch, 2017, ISBN 978-3-946509-11-0

- Arthur L. Smith: The Missing Million - On the Fate of German Prisoners of War after World War II. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1992, ISBN 978-3486645651

- Josef Nowak: People sown in the field. Niemeyer Verlag Hameln, 1990, ISBN 978-3875859058

- Dietrich Kienscherf: How I became PoW No. 3 214 570. Verlag Lenover Neustrelitz, 1995, ISBN 978-3930164127

- James Bacque: The Planned Death: German Prisoners of War in American and French Camps 1945-1946. Pour le Mérite, 2008, ISBN 978-3932381461

Web links

- State Center for Political Education, Rhineland-Palatinate - Rheinwiesenlager

- Team Rehorst: Rheinberg - Short report: Unusual finds in the Rheinberg POW camp

- Thomas Krüger and Christina Maassen: Rheinisches Amt für Bodendenkmalpflege - excavations, finds and findings 2001 and 2002; Excavation report on the investigation of the ground monument in Rheinberg (p. 349, modern times). PDF as digitized version from Heidelberg University Library (15.3 MB)

- Fritz Schubert: Camps in Büderich and Rheinberg - Americans are looking for the truth of horror; in RP-Online from April 24, 2019

- Interview with Merrit Peter Drucker from Moriz Schwarz "Rheinwiesenlager: US Major Merrit Drucker asks for forgiveness", in Volks Betrug.net from December 8, 2014 (Memento on Wayback Machine from September 26, 2019)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The administrative report of the city of Rheinberg from 1945–1955 speaks of up to 140,000 prisoners of war.

- ↑ There are various details about the number of people within a cage. Depending on the source, they vary from 8,000 to 50,000 people. In the early days of the camp and during the merger with the Büderich camp, the cages were overcrowded. Due to the displacement of prisoners as forced laborers in Belgian and French coal mines and camps, those who died of disease and hunger, those who had been released and those who had fled, their numbers fluctuated extremely.

- ↑ Here, too, no exact numbers have been reported. See: Arthur L. Smith "The Missing Million" from page 45.

- ↑ Stream near Saalhoff .

- ↑ Shortly afterwards, further Rhine meadow camps were set up to accommodate the crowded crowds. The camps were numbered in the order in which they were built.

- ↑ Many of them were RAD maiden . They were used as a substitute for male workers in agriculture, military service in the offices, armaments factories or rail transport. As Wehrmacht helpers (Blitzmädel) they became radio operators, operated FLAK searchlights and FLAK guns and flew with the night fighter units of the Luftwaffe.

- ↑ The water for the prisoners was not always taken from the Rhine, but from the Fossa Eugeniana or the Heydecker Ley. It is true that the Allies prohibited the drilling of new shafts. By introducing water from the coal washing plant at the Rossenray colliery in Kamp-Lintfort, that was a rather filthy dryness. In addition, the sewage treatment plant was badly affected by the bombing. The Americans, on the other hand, supplied themselves with clean drinking water from the wells of the confiscated homesteads and the pumping communities.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Janßen: For Eisenhower the Germans were beasts. In: Zeit Online. Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius GmbH & Co. KG, December 8, 1989, accessed on September 29, 2019 .

- ↑ One of the reasons for this was the planned handover of the camp to the British and French allies. Due to debts caused by the war and outstanding accounts with the European allies, the Americans saw no further concern for the prisoners in the German camps.

- ↑ What is meant is the camp on St.-Jan-Feld in Weeze. It was located near the Sent Jan Chapel.

- ↑ 15 km on foot doesn't sound like much at first. However, the prisoners from the Büderich camp (PWTE A4) were completely emaciated, suffered from typhus, dysentery, pneumonia, severe ulcers and were partially disabled during the war. It went down in history as the “hunger march”.

- ↑ After Camp B became vacant, it was converted into a labor camp. The detached columns of prisoners were used to clear rubble, repair roads, and carry out loading work. The British later used them as slave labor in agriculture, logging and in the mines. A place in the workers' column was very popular with the inmates of the Rhine meadow camp, as it gave them more food. The prospect of two more slices of bread prompted many intellectuals to be hired as simple workers. They asked ordinary people about the theoretical basics. However, a lack of practice and unfamiliar work often resulted in serious injuries and death.

- ↑ Peter Bußmann: The prisoner-of-war camp was established in Rheinberg 70 years ago. In: NRZ. Funke Medien NRW, April 21, 2015, accessed on September 26, 2019 .

- ↑ IKLK Karl Leiser: Rheinberg: Karl Leisner in St. Peter. Retrieved September 26, 2019 .

- ^ Franziska Gerk: Rheinbergs place of remembrance. In: NRZ. Funke Medien NRW, July 28, 2014, accessed on September 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Merrit P. Drucker: Without any protection: An apology from Merrit Drucker. Focus Online, December 12, 2011, accessed September 26, 2019 .