Short-eared elephant

| Short-eared elephant | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides proboscideus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Macroscelides proboscideus | ||||||||||||

| ( Shaw , 1800) |

The macroscelides proboscideus ( Macroscelides proboscideus ), sometimes known as short ear elephant shrew referred to is a mammalian species in the genus Macroscelides and the family of shrews (Macroscelididae). It is widespread in the south-western part of Africa and inhabits the partly dry, semi-desert regions of the Karoo . The trunk-like snout and the stocky build with thin limbs are characteristic. In the Karoo the short-eared elephant lives terrestrially as a fast runner and uses grazing areas with numerous natural shelters. As an omnivore , it mainly eats plants and insects . The animals form monogamous pair bonds that usually last for their entire life, females give birth to one or two young several times a year. The species was described in 1800, making it the oldest known scientifically known representative of the elephant. In the second half of the 20th century in particular, the short-eared elephant was the only representative of the genus Macroscelides , and two other species have been described since 2012. The stock is not considered to be threatened.

description

The short-eared trumpet is a small representative of the trunk and has a round body and a round head. The head-trunk length is 10 to 11 cm, the tail length varies from 11 to 13 cm. As a result, the tail is on average longer than the rest of the body. The weight varies between 31 and 47 g. The total length of five individuals from Namibia examined in June 2007 was between 22.4 and 23.6 cm, their weight was between 26 and 37.5 g. With the dimensions given, the short-eared elephant represents one of the smallest species in the family, but is on average larger than the related Etendeka short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides micus ). There is no pronounced sexual dimorphism between the sexes . Characteristic is the long, trunk-like snout with large vibrissae , which reach a length of 55 mm. The ear has a round and wide shape and has fine white hair on the inside. Compared to the Etendeka short-eared trumpet, the upper edge of the ear extends over the head. With a length of about 21 to 29 mm, the ears are not particularly shorter than those of other representatives of the elephant. The eyes reach a moderate size, but are smaller than in the elephant shrews ( Elephantulus ) and, unlike these, do not have a light eye ring. The soft fur is colored yellowish-brown to gray on the upper side, the underside and the flanks are tinted lighter, whereby the coloring here can change from light gray to whitish. The hair is up to 17 mm long and has a dark base. On the tail there are darker hairs on the top and lighter on the underside. Towards the end of the tail, the hair becomes longer, so that the tip appears slightly bushy. Glands appear on the underside of the tail, but they are not always visible in the short-eared elephant. If they appear externally visible, they reach a length of 8 to 12 mm, which is only around 10% of the total tail length. In comparison, the glands in the Etendeka short-eared elephant take up almost a third of the length of the tail. The skin that is partially visible under the fur covering, for example on the ears, shows dark pigmentation . In this respect, the short -eared elephant resembles the Namib short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides flavicaudatus ), but this has an overall lighter coat color. The thin hind limbs are typically significantly longer than the front legs. Both hands and feet each have five rays that have claws. The rear foot measures between 32 and 36 mm in length.

distribution and habitat

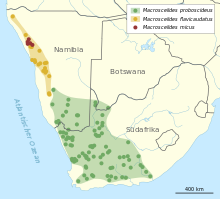

The short-eared elephant is endemic to southwest Africa . He lives in southern and western South Africa , southern Namibia and the most southwestern part of Botswana . The habitat includes dry regions, mostly deserts and semi-deserts , mainly the so-called Karoo . Sandy and gravelly plains dominate here, but they are often relatively thickly covered with tussock and bush vegetation. The bushes can be up to 1 m high. The annual average temperatures in the Karoo fluctuate around 15 to 19 ° C, the annual precipitation is 66 to 200 mm. The height distribution ranges from sea level in the Succulent Karoo to 1400 m in the Nama Karoo. The entire distribution area is around 500,000 km², possibly more. The population density is considered to be very low. According to studies in the Goegap Nature Reserve in South Africa between 2005 and 2007, it fluctuated between 0.35 and 1.59 individuals per hectare. The two other representatives of Macroscelides have an area further north, which is largely in the Namib . A 50 km wide corridor in the NamibRand nature reserve separates the range of the short-eared elephant from that of the Namib short-eared elephant.

Way of life

Territorial behavior

The short-eared elephant is a terrestrial animal that can move very quickly ( cursorial ) and can reach speeds of up to 20 km / h. He lives both at night and at twilight, the main activities begin around 7:00 p.m. and end in the early hours of the morning around 9:00 a.m. The animals are rarely seen in the afternoon. The individual animals maintain activity rooms that they use over a longer period of time. According to studies in the Goegap Nature Reserve, the size of the individual tail areas is an average of 1.7 ha for males and 0.7 ha for females. The size increases slightly during the rearing of young animals. Another influencing factor is the population density. Thus, in regions with a low number of individuals, the areas where males can work can be significantly larger and reach almost 3 hectares, whereas this has less of an effect on females. This may help the dams to minimize the risk of being caught by predators. Despite the sometimes fluctuating extent of the territory, the ranges of the short-eared elephants in the Karoo are significantly smaller than those of their relatives in the Namib , which can be up to 100 hectares in size. The incidence of territorial overlap in individuals of the same sex is very low, as is the case between the two sexes, suggesting a certain degree of territoriality in both males and females. In general, live with their elephant-shrews males and females in monogamous couple relationships, which may persist until the death of a partner. The joint activities are largely limited to the time shortly before and during the rut . Then the male stays near the female, follows him and superimposes those of his partner with his scent marks. In this phase, males also defend their partner's territories against other conspecifics living in pairs. Due to this behavior, which is sometimes limited in time, the monogamous pair bonds in the short-eared elephant are rather loose, as males sometimes visit two or more females. This occurs mainly when female animals have lost their partner. As a rule, however, the tied male returns to his own home area some time later, usually when an unbound male also follows the female without a partner. The short-eared elephant uses various hiding places that are distributed in the individual action areas. The hiding places consist of crevices or rock overhangs, lie under rocks and bushes, the entrances are often covered by vegetation. However, no special nests are created in the shelters.

nutrition

The short-eared elephant is an omnivore that eats both insects and plant material. Overall, according to studies in the Karoo, the diet includes an average of 46.5% insects, 48.4% are plants, the remaining 5% are seeds . It is noticeable that females usually eat more insects than males, which may be with them the higher energy consumption and thus the greater need for protein-rich food during the pregnancy and breastfeeding phase of the young animals. However, there are regional and seasonal differences. In the western areas of the Succulent Karoo, the proportion of insects and plants is more or less the same over the year. In the more eastern distribution areas, which are characterized by two rainy seasons, there are stronger variations. The annual share of insects is 63%, that of plants 36.7%. In summer up to 77.4% of insects are exterminated, in individual cases even up to 88%, in winter, however, only 42.5%. During this time of year, which is dry in contrast to the western areas, the consumption of plants increases, as insects are much less common. In comparative studies of several sites within the distribution area, a high individual variation in diet was found. It should be emphasized, however, that the frequent presence of insects does not necessarily increase the consumption of these by the short-eared elephant.

Reproduction

Reproduction takes place throughout the year, with the females oestrus beginning about every 10 weeks. Pregnant females can often be seen in summer (September to February), while numbers decline sharply in early winter from March to July. According to studies in the Goegap Nature Reserve, the average reproduction period for each animal is around eight months a year, during which females have offspring two to three times. The monogamous way of life means that the male accompanies his partner especially before and during the rut . Shortly before the onset of oestrus, the female animals rub their scent glands of the ano-genital area on the floor and thus deposit a secretion that is covered only a short time later by the male's own scent mark, which indicates the existing partnership. The gestation period lasts an average of 56 days, during this time the weight of the female increases by up to 20 g - one examined individual weighed 64.3 g shortly before birth - which corresponds to about half the normal weight of the mother animal. After that, the female usually gives birth to one or two young animals. The birth of three boys could very rarely be observed in human care. The birth takes place in a shelter that regulates the temperature differences between day and night. The structure of the offspring is separated from that of the male or female parent animal; a special nest is also not set up in it. The newborns are well developed when they are born, they have a soft fur and open eyes. Their weight is around 9 g. During the rearing period there is no direct care of the offspring by the father animal, the mother animal only visits the young irregularly to suckle, on average once a day. The suckling period is relatively short and lasts about two to three weeks. Already on the fifth day the young animals eat insect food. This is initially collected and pre-chewed by the mother. At the end of the suckling season, the young begin to go on longer excursions that go up to 240 m. After around six weeks, they are sexually mature and independent. Since the oestrus starts again a few days after the birth of the offspring, the female can already give birth to new offspring while the young are being raised. Life expectancy in the wild is unknown, but it is assumed that it is one to two years, similar to that of the closely related elephant shrews. Animals kept in human care lived up to eight years and eight months.

Predators and parasites

The barn owl is one of the most important predators , and remains of the short-eared elephant have been found in their crust. In case of danger, an animal runs from bush to bush and hides in a shelter if necessary. The main external parasites are fleas , the genera Echidnophaga and Xenopsylla being important . In addition, ticks have also been detected, including Rhipicephalus and Haemaphysalis .

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of elephants according to Heritage et al. 2020

|

The short-eared elephant is a species from the genus Macroscelides . Today, a total of three species are assigned to this genus, two species were only established after 2010. Macroscelides forms part of the elephant family (Macroscelididae) within the order of the same name of the elephant (Macroscelidea). This group of smaller mammals native to Africa is divided into two subfamilies. To the Rhynchocyoninae only be shrew ( Rhynchocyon ) referred to, they are characterized monotypic . The elephants, which are also the largest representatives of the elephants, mostly inhabit wooded habitats . The Macroscelidinae form the second subfamily, which in addition to Macroscelides also includes the elephant shrews ( Elephantulus ), the trunk rat ( Petrodromus ), the Somali elephant shrew ( Galegeeska ) and the North African elephant shrew ( Petrosaltator ). All representatives of the Macroscelidinae are adapted to clearly drier open landscapes to sometimes desert-like regions. Molecular genetic investigations revealed a closer relationship between Macroscelides and Galegeeska , Petrodromus and Petrosaltator . The two subfamilies separated from the line of their common ancestors in the Lower Oligocene about 32.8 million years ago; a greater diversification of the Macroscelidinae took place from the Upper Oligocene about 28.5 million years ago. Macroscelides formed the Lower Miocene around 19.1 million years ago.

|

Internal systematics of Macroscelides according to Dumbacher et al. 2014

|

The taxonomic history of the genus Macroscelides is complex. In the first half of the 20th century, the short-eared elephant was divided into two types with up to 10 subspecies in use. In addition to M. proboscideus , M. melanotis was also considered a recognized species. A revision of the genus in 1968 resulted in M. proboscideus only being a valid species that contained two subspecies. Accordingly, M. p. proboscideus to the Karoo areas in South Africa , which are characterized by darker landscape tones and areas more strongly influenced by shadow. M. p. flavicaudatus, on the other hand, lived in the lighter and sunnier regions of the Namib further north. The sometimes varied fur drawings were seen as an adaptation to local habitat conditions. Until the beginning of the third millennium, the short-eared elephant was the only species within the genus Macroscelides . However, the occurrence and number of the subspecies was discussed. Molecular genetic investigations carried out only at the beginning of the 21st century combined with field research on site provided evident evidence of a more differentiated subdivision of the genus. The genetic analyzes were able to separate a northern and a southern population , which was also confirmed by the on-site investigations, which showed a spatial separation of the two groups. Due to the genetic isolation of the two groups, which has also been proven, the researchers involved recorded the subspecies M. p. flavicaudatus in the species status, whereby the Namib short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides flavicaudatus ) formed the second recognized species of the genus Macroscelides next to the short-eared elephant . With the Etendeka short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides micus ), a third species, regionally sympathetic to the Namib short-eared elephant, was added two years later . Due to the re-evaluation of M. p. flavicaudatus as an independent species, no subspecies of the short-eared elephant are distinguished today.

The first scientific description of the short-eared elephant was in 1800 by George Shaw . It took place under the species name Sorex proboscideus , with which Shaw placed the species among the red-toothed shrews. Shaw named the brown coat color and the noticeably long nose as special characteristics. He gave the Cape of Good Hope as a probable type area , which was specified in 1951 by Austin Roberts in Roodewal, Oudthoorn, Cape Province (now Western Cape ). The short-eared elephant is thus the earliest described member of the elephant in terms of research history.

Threat and protection

Despite the relatively small area that the short-eared elephant inhabit, no major threats to the population are known. Locally, especially near rivers, the landscape is dominated by small-scale or industrial agriculture, as well as by the expansion of urban settlement centers. The associated desertification or bush cover can also have a negative impact on the habitats of the short-eared elephant, but these changes currently only appear on a small scale. Because of this, the IUCN sees the stock as “not endangered” ( least concern ).

The short-eared elephant jumper is often present in zoological institutions, especially in Europe due to the low accommodation costs, the high attractiveness and the generally frequent breeding successes. Since the 1990s there have been an average of 24 to 25 keepers with a total of around 100 animals in Germany alone. One of the most important breeds is located in the Wuppertal Zoo , and another since 2010 in the Minis Zoo in the Ore Mountains Aue .

literature

- John P. Dumbacher, Galen B. Rathbun, Timothy O. Osborne, Michael Griffin and Seth J. Eiseb: A new species of round-eared sengi (genus Macroscelides) from Namibia. Journal of Mammalogy 95 (3), 2014, pp. 443-454

- Stephen Heritage: Macroscelididae (Sengis). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2018, pp. 206-234 (p. 229) ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4

- Ronald M. Nowak: Walker's Mammals of the World . Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999 ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- Mike Perrin and Galen B. Rathbun: Macroscelides proboscideus Round-eared Sengi (Round-eared Elephant-shrew). In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume I. Introductory Chapters and Afrotheria. Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp. 277-278

- Galen B. Rathbun: Macroscelides proboscideus (Shaw, 1800) - Round-eared elephant-shrew. In: John D. Skinner and Christian T. Chimimba (Eds.): The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 25-27

- Don E. Wilson and DeeAnn M. Reeder (Eds.): Mammal Species of the World . 3rd edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e John P. Dumbacher, Galen B. Rathbun, Timothy O. Osborne, Michael Griffin and Seth J. Eiseb: A new species of round-eared sengi (genus Macroscelides) from Namibia. Journal of Mammalogy 95 (3), 2014, pp. 443-454

- ↑ a b c d Melanie Schubert, Neville Pillay, David O. Ribble and Carsten Schradin: The Round-Eared Sengi and the Evolution of Social Monogamy: Factors that Constrain Males to Live with a Single Female. Ethology 115, 2009, pp. 972-985

- ↑ a b c d e Gea Olbricht and Alexander Sliwa: Elephant shrews - the little relatives of elephants? Journal of the Cologne Zoo 53 (3), 2010, pp. 135–147

- ↑ a b c d e Galen B. Rathbun: Macroscelides proboscideus (Shaw, 1800) - Round-eared elephant-shrew. In: John D. Skinner and Christian T. Chimimba (Eds.): The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 25-27

- ↑ a b c d e f g Mike Perrin and Galen B. Rathbun: Macroscelides proboscideus Round-eared Sengi (Round-eared Elephant-shrew). In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume I. Introductory Chapters and Afrotheria. Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp. 277-278

- ↑ a b c d e Stephen Heritage: Macroscelididae (Sengis). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2018, pp. 206-234 (pp. 229-230) ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4

- ^ A b c John P. Dumbacher, Galen B. Rathbun, Hanneline A. Smit and Seth J. Eiseb: Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the Round-Eared Sengis or Elephant-Shrews, Genus Macroscelides (Mammalia, Afrotheria, Macroscelidea). Plos ONE 7 (3), 2012, p. E32410

- ^ A b Galen B. Rathbun and Hanneline Smit-Robinson: Macroscelides proboscideus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. ( [1] ); last accessed on July 1, 2015

- ↑ Lizanne Roxburgh and MR Perrin: Temperature regulation and activity pattern of the Round-eared Elephant shrew (Macroscelides proboscideus. Journal of thermal Biology 19 (1), 1994, pp. 13-20

- ↑ a b Melanie Schubert, Carsten Schradin, Heiko G. Rödel, Neville Pillay and David O. Ribble: Male mate guarding in a socially monogamous mammal, the round-eared sengi: on costs and trade-offs. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 64, 2009, pp. 257-264

- ^ Galen B. Rathbun: Why is there discordant diversity in sengi (Mammalia: Afrotheria: Macroscelidea) taxonomy and ecology? African Journal of Ecology 47, 2009, pp. 1-13

- ↑ Graham IH Kerley: Small mammal seed consumption in the Karoo, South Africa: further evidence for divergence in desert biotic processes. Oecologia 89, 1992, pp. 471-475

- ↑ Graham IH Kerley: Trophic status of small mammals in the semi-arid Karoo, South Africa. Journal of Zoology 226, 1992, pp. 563-572

- ^ Graham IH Kerley: Diet of small mammals from the Karoo, South Africa. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 19, 1989, pp. 67-72

- ^ MJ Lawes and MR Perrin: Risk-sensitive foraging behavior of the round-eared elephant shrew (Macroscelides proboscideus). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 37, 1995, pp. 31-37

- ^ Graham IH Kerley: The Round-eared Elephant-Shrew Macroscelides proboscideus (Macroscelidea) as an omnivore. Mammal Review 25, 1995, pp. 39-44

- ^ RTF Bernard, GIH Kerley, T. Doubell and A. Davison: Reproduction in the round-eared elephant shrew (Macroscelides proboscideus) in the southern Karoo, South Africa. Journal of Zoology 240, 1996, pp. 233-243

- ↑ Gea Olbricht, C. Kern and G. Vakhrusheva: Some aspects of the reproductive biology of short-eared elephants (Macroscelides proboscideus A. Smith, 1829) in zoological gardens with special consideration of triplet litters. Der Zoologischer Garten 75, 2005, pp. 304-316

- ↑ EG Sauer: On the social behavior of the short-eared elephant shrew Macroscelides proboscideus. Zeitschrift für Mammaliankunde 38, 1973, pp. 65-97

- ↑ Richard Weigl: Longevity of Mammals in Captivity; from the Living Collections of the World. Kleine Senckenberg-Reihe 48, Stuttgart, 2005, ISBN 3-510-61379-1

- ^ Gea Olbricht: Longevity and fecundity in sengis (Macroscelidea). Afrotherian Conservation 5, 2007, pp. 3-5

- ↑ LJ Fourie, JS du Toit, DJ Kok and IG Horak: Arthropod parasites of elephant-shrews, with particular reference of ticks. Mammal Review 25, 1995, pp. 31-37

- ↑ Steven Heritage, Houssein Rayaleh, Djama G. Awaleh and Galen B. Rathbun: New records of a lost species and a geographic range expansion for sengis in the Horn of Africa. PeerJ 8, 2020, p. E9652, doi: 10.7717 / peerj.9652

- ↑ Hanneline Adri Smit, Bettine Jansen van Vuuren, PCM O'Brien, M. Ferguson-Smith, F. Yang and TJ Robinson: Phylogenetic relationships of elephant-shrews (Afrotheria, Macroscelididae). Journal of Zoology 284, 2011, pp. 133-143

- ^ Mike Perrin and Galen B. Rathbun: Order Macroscelidea - Sengis (Elephant-shrews). In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume I. Introductory Chapters and Afrotheria. Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp. 258-260

- ↑ John P. Dumbacher, Elizabeth J. Carlen and Galen B. Rathbun: Petrosaltator gen. Nov., A new genus replacement for the North African sengi Elephantulus rozeti (Macroscelidea; Macroscelididae). Zootaxa 4136 (3), 2016, pp. 567-579

- ↑ Don E. Wilson and DeeAnn M. Reeder (eds.): Mammal Species of the World . 3rd edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4 , p. 472

- ↑ George Shaw: General Zoology or Systematic Natural History. Volume I Part II. Mammalia. London, 1800, pp. 249–552 (p. 536) ( [2] )

- ↑ a b Zoo animal list ( [3] ), last accessed on October 16, 2018

- ^ Galen B. Rathbun and Laurie Bingaman Lackey: A brief graphical history of sengis in captivity. Afrotherian Conservation 5, 2007, pp. 7-8

Web links

- Macroscelides proboscideus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2015 Posted by: Rathbun & Smit-Robinson, 2013. Retrieved on July 1, 2015.

- http://members.aon.at/ruesselspringer