Macroscelides

| Macroscelides | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides proboscideus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Macroscelides | ||||||||||||

| A. Smith , 1829 |

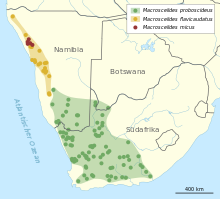

Macroscelides is a genus from the family and order of the elephants (Macroscelididae, Macroscelidea). It includes the smallest representatives of the entire classification group. The distribution is limited to southwest Africa , where the three species of the genus predominantly populate dry to very dry landscapes, especially the Karoo in South Africa and the Namib in Namibia . The population density is considered to be very low. The animals are nocturnal and crepuscular as well as ground dwelling and live in monogamous relationships, whereby the common activities are limited to the reproductive phase. The individual individuals use grazing areas, the size of which varies depending on the region. Females give birth to one or two young animals up to three times a year, which arewell developedas nests . Plants and insects serve as main food, so that the representatives of the genus Macroscelides are to be regarded as omnivores . In the second half of the 20th century,only one species was knownwith the short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides proboscideus ), the genus was therefore considered to be monotypical . It was not until the beginning of the 21st century thattwo further species could be describedwith the Namib short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides flavicaudatus ) and the Etendeka short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides micus ). The entire population of Macroscelides is currently considered safe.

features

Habitus

Macroscelides includes the smallest representatives of the elephant . The total length varies from 17.0 to 23.5 cm, sometimes up to 24.8 cm, the tail length amounts to 8.4 to 13 cm and thus slightly exceeds the head-torso length (about 105% of the length of the rest of the body). The weight varies between 19 and 47 g. Particularly noticeable are the rounded body and the equally shaped head, which also has the trunk-like, elongated, highly mobile nose of all elephants, which protrudes up to 12 mm above the incisors in Macroscelides . As with all elephants, the mouth is small and inferior. The ears show a strikingly wide and round profile and, at 17 to 29 mm in length, are only slightly smaller than those of the elephant shrews ( Elephantulus ). The tragus is large and thin and, unlike the elephant shrews, almost hairless. The eyes reach a moderate size, they lack the light eye ring characteristic of the elephant shrews. The fur is very soft, the individual hairs can be up to 17 mm long. The color of the fur on the back varies depending on the species, from brownish to rust-colored to light gray. The hair base is often colored darker. On the other hand, lighter tones predominate on the stomach. The tail is only slightly hairy in the front area, the hair becomes thicker towards the rear and the end looks partly bushy. Scent glands appear on the underside of the tail , which, depending on the species, can be of different sizes and clearly visible. Female animals also have three pairs of teats . The slender and elongated limbs are also a noticeable feature, with the front ones appearing significantly shorter than the rear ones. Arms and legs each end in five toes with long claws. The inner toe of the rear foot (hallux, ray I) is very short and ends with its claw tip at about half the length of the following outer toes. The length of the rear foot is 28.5 to 38 mm.

Skull and dentition features

The skull of Macroscelides reaches a length of 32 to 35 mm and a width of 20 to 22 mm on the zygomatic arches . When viewed from above, it shows an approximately triangular shape, as with all elephants. In Macroscelides it is built much wider and has a relatively shorter and slimmer rostrum than the other representatives of the elephant. In addition, the skull is strongly rounded when viewed from the side and has relatively large eye sockets . The most conspicuous characteristic of the skull is the extremely large tympanic bubble on the temporal bone . It is clearly bulged due to pneumatization and also shifted further outwards than in the elephant shrews . As a result, when viewed from above, it protrudes beyond the rear and side edge of the skull, only the zygomatic arches protrude further. Due to its size, it takes up areas of the wart part , the scaly part , the parietal bone and the occiput , the occiput is markedly narrowed and the parietal and frontal bones are pushed forward. On the top of the skull, the bulge creates an approximately 4 mm wide sagittal gap. The total volume of the middle ear is 748 mm³, the right and left auditory chambers taken together correspond to 130% of the brain volume. In addition to the kangaroos , the species of Macroscelides have the most spacious middle ears in terms of body and head size. There are three characteristic pairs of openings in the median jawbone and the palatine bone , which are similar in number and size to the elephant shrews and the proboscis , but do not appear in the same way in the proboscis . The lower jaw is short and slender and has high joint ends. The bit has the following dental formula of: . Overall, the representatives of Macroscelides have 40 teeth. The teeth are in a closed row due to the short rostrum. The incisors are rather small, the first upper one has only one cusp, while the second upper one has two, as does the first upper premolar . The shape of the canine resembles the incisors ( incisiform ). Sharp tips ( sectorial ) appear on the two middle premolars of the lower jaw, which are very narrow overall . The molars are generally much higher crowned than in the elephant shrews. The entire row of teeth in the upper jaw is between 15.0 and 16.3 mm long.

distribution

Macroscelides is common in south-western Africa . The species mainly inhabit the arid desert and semi-desert regions. They are therefore mainly to be found in the Karoo in South Africa and in the Namib in Namibia . Both habitats are characterized by a sandy-stony subsoil, with the Karoo appearing more humid and rich in vegetation compared to the Namib. The altitude distribution ranges from sea level to around 1400 m. The representatives of the genus Macroscelides live in an area of around 500,000 km², but the distribution area is not closed. In the area of the NamibRand nature reserve , the southern Karoo populations are separated from the northern ones of the Namib by a 50 km wide strip. In general, the Macroscelides species are not very common. The population density depends on the ecological conditions of the respective region. In the vegetation-rich areas of the Karoo up to 1.5 individuals per hectare (= 150 ind. Per km²) can be found, in the extremely dry Namib the population density goes back to one individual per km².

Way of life

Territorial behavior

The representatives of the genus are mostly active at night and at dawn, but can also occur during the day. They live terrestrially, where they walk and sometimes jump ( saltatory ) due to their long hind legs , although no purely bipedal gait is formed. The speeds achieved are up to 20 km / h, which means that the animals can be seen as moving very quickly for their size ( cursorial ). The individual animals use activity spaces that are maintained over a longer period of time, but their size varies greatly. In the dry and sparsely overgrown Namib , the activity areas can reach a size of up to 100 ha , in the more densely vegetated succulent Karoo , where the population density is also higher, the activity area size is between 0.8 and 1.7 ha, with the males is on average larger than that of females. The individual territories hardly overlap, neither within nor between the sexes. As a result, there is a certain territoriality. With all elephants, males and females live in more or less monogamous relationships, which can last until one partner dies. This form of the social system, which is rather unusual among mammals, is dependent on ecological factors, such as the availability of food resources, which in turn influences the size of the territories and has repercussions on social ties and consequently on reproduction. Studies in the extremely dry Namib show that the animals there, with their very large individual grazing areas, tend to have less territoriality and greater variability in their choice of mate. In the less dry Karoo of South Africa, where the action areas are much smaller, an increased monogamous way of life could be demonstrated. In fact, the monogamous pairing of short-eared elephants seems to be rather loose overall. On the one hand, males in the Karoo sometimes visit several - mostly partnerless - females, on the other hand, outside the mating season, there are hardly any joint activities between the pairs, rather the animals avoid each other.

Within the action rooms there are several shelters that not only serve as hiding places, but are also necessary to compensate for the extreme temperature differences between day and night. These mostly include crevices or rock overhangs, holes in the ground and bushes. In regions with soft ground, such as in the Namib, the animals dig their own earthworks, otherwise they also use the hiding places created by other ground graves, such as gerbils or meerkats . The burrows can sometimes extend a few meters into the ground and have several entrances and exits, which are often covered by vegetation. No special nests are set up in the hiding spots. The animals take turns using the individual shelters, sometimes they just inspect them. The representatives of Macroscelides create paths between the individual living quarters and feeding areas by clearing away stones and twigs with their forefeet. The paths can be several hundred meters long in dry areas and are marked out as straight lines. They are mainly used to move quickly between the individual stopover points and to escape from predators. These trails have mainly been described for the eastern populations of the Namib and generally assigned to the short-eared elephant ( M. proboscideus ). Investigations in 2007 showed that M. flavicaudatus also creates and uses such paths in the vegetation-poor Namib, but this has not yet been confirmed for M. proboscideus in the more densely vegetated Karoo.

In addition to the scent glands under the skin and the associated sense of smell , hearing and eyes are primarily used to communicate with one another . In addition to individual squeaking noises, the animals often produce drum-like noises, which are caused by beating their hind feet on the ground in quick succession. This form of communication, known as podophony , is very common among elephants and usually occurs under stress; due to its great variation, it has taxonomic value for differentiating between species. With the short-eared trunk jumper, the drum series is very short and comprises less than ten beats in a row (mostly three), which occur at regular intervals with a cadence of around 50 to 80 ms.

Diet and thermoregulation

The representatives of Macroscelides eat omnivorous , the main food is insects - mostly ants and termites - as well as plants. However, the exact composition can vary depending on the season . Insects predominate in summer, whereas plants predominate in winter. On average, female animals eat more insects, which may be related to the increased energy consumption in rearing the offspring and the associated milk production. The food is scented on the ground with the long nose via the sense of smell, while the intake takes place with the long tongue, which can be stretched out several millimeters in front of the tip of the nose.

The thermoregulation is atypical for small mammals in arid regions. The body temperature remains relatively constant despite the outside temperature varying between 5 and 38 ° C and is 35 to 39 ° C. In the range of 10 to 25 ° C outside temperature, it averages around 36 ° C. Body temperature only changes at higher or lower temperatures in the environment. The stability is achieved through various behaviors of Macroscelides , for example sunbathing in the early morning hours or staying in the shelter in cool conditions and thus adapting the daily routine to the corresponding weather conditions. In addition, the representatives of Macroscelides can fall into a cold rigor ( torpor ) when there is little food supply combined with low ambient temperatures of around 10 to 15 ° C. The torpor lasts from less than an hour to around 18 hours. As a rule, short periods of rigidity up to a maximum of 8 hours predominate, but at an ambient temperature of only 10 ° C they become significantly longer and exceed 12 hours and more. Torpor does not occur if enough food is available despite the low ambient temperature. During freezing, the body temperature drops close to the outside temperature and can drop below 17 ° C, the lowest measured temperature being 9.4 ° C, which is lower than that of most mammal species that go through similar torpor phases. The value is close to what is known for winter sleepers . In addition, Macroscelides has efficient water storage in the rectum combined with little loss of water on the surface of the skin (transpiration). The liquid is largely absorbed through food, and the moist conditions in the hiding places also serve to balance the water balance. In addition, as an adaptation to the living conditions in desert-like landscapes , the kidneys are able to store water for longer, but their suitability for the production of highly concentrated urine is not quite as pronounced as in the elephant shrews .

Reproduction

Reproduction is possible all year round, but mostly takes place in the spring and summer months. Shortly before the onset and during the oestrus in the female animal, the male begins to follow this, which starts the time for the mutual activities of the individual couples. The gestation period is around 56 days, after which one or two young are born. These are refugees and have open eyes and soft fur. You spend the first time in a shelter, which is separated from the hiding place of the father and mother animal. There is no paternal care of the offspring, the mother only visits the young animals irregularly to suckle, usually once a day. This type of rearing of the offspring is referred to as the "mother's absenteeism system" and may serve to keep the young largely odorless, so that they are better protected from the detection of predators. The suckling period lasts only two to three weeks, but after a few days the young animals start to eat solid food. After about six weeks, the offspring are sexually mature. Life expectancy in the wild is unknown but is estimated to be two years.

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of elephants according to Heritage et al. 2020

|

Macroscelides is a genus from the family of the elephants (Macroscelididae) within the German order of the elephants (Macroscelidea). The elephants are a group of mammals found only in Africa . You are assigned a total of six genera, which are divided into two subfamilies. The Rhynchocyoninae include the proboscis dog ( Rhynchocyon ) as the only member, they are thus monotypical . The elephant dogs are not only the largest representatives of the elephants, but are also the only group to be found in predominantly wooded habitats . Opposite them are the Macroscelidinae . In addition to Macroscelides , these include the elephant shrews ( Elephantulus ), the proboscis ( Petrodromus ), the Somali elephant shrew ( Galegeeska ) and the North African elephant shrew ( Petrosaltator ). All representatives of the Macroscelidinae are adapted to rather dry open landscapes up to desert-like regions. According to molecular genetic studies, Macroscelides is the sister group of a clade that consists of Petrodromus and Petrosaltator . In addition to the molecular genetic examinations, analyzes of the skull design and especially the ear indicate this. For this reason, Macroscelides , Galegeeska , Petrodromus and Petrosaltator are united in the tribe of Macroscelidini , which face the Elephantulini with the elephant shrews . The separation of the two subfamilies, Rhynchocyoninae and Macroscelidinae, already took place in the Lower Oligocene about 32.8 million years ago, a greater diversification of the Macroscelidinae took place from the Upper Oligocene about 28.5 million years ago.

|

Internal systematics of Macroscelides according to Dumbacher et al. 2014

|

The genus Macroscelides comprises three recent species:

- Namib short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides flavicaudatus Lundholm , 1955); in the Namib of Namibia

- Etendeka short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides micus Dumbacher, Rathbun, Osborne, Griffin & Eiseb , 2014); in the Etendeka region of Namibia

- Short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides proboscideus ( Shaw , 1800)); in the Karoo from South Africa to Namibia

The first scientific description of Macroscelides was in 1829 by Andrew Smith . He presented a comprehensive description of the dentition and also highlighted the long, trunk-like snout, the medium-sized eyes and, above all, the clearly long hind legs compared to the front legs. The generic name Macroscelides , which is made up of the Greek words μακρὁς ( macros “large”) and σκέλος ( skélos “leg”) , also refers to the latter .

Research history

The taxonomic history of Macroscelides is complex. The short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides proboscideus ) was introduced by George Shaw as early as 1800, but he made the first description under the name Sorex proboscideus . With that, Shaw referred the short-eared elephant to the red-toothed shrews . Almost three decades later, in 1829, Andrew Smith established the species M. typus (which he himself corrected to M. typicus in 1838) in addition to the generic name Macroscelides . In the course of the 19th century, numerous new species of elephants were described, which were often assigned to Macroscelides . Quite a few of these new forms showed deviations from Macroscelides in some anatomical features . For this reason, in 1906, Oldfield Thomas and Harold Schwann split off the newly named genera Elephantulus and Nasilio , which both differed from Macroscelides by their less inflated tympanic bladders (but had a different number of back molars among each other), and assigned them to a larger part the well-known representative too. This reduced the number of species of Macroscelides to four in the first half of the 20th century. In a revision of the genus carried out by Austin Roberts in 1951 , he recognized only two species, M. melanotis and M. proboscideus , but he assigned a total of nine subspecies to the latter. A tenth subspecies, M. proboscideus flavicaudatus, was introduced four years later by Bengt Lundholm . Another revision of the elephants by Gordon Barclay Corbet and John Hanks in 1968 only revealed one valid species, M. proboscideus . The up to ten different subspecies, the distinction of which was mostly based only on varying coat colors and differing, average body dimensions, were reduced to two. The nominate form M. p. proboscideus darker colored forms from the largest area of southern Africa and M. p. flavicaudatus lighter specimens that were more native to northern Namibia. This gave the genus Macroscelides the status of a monotypic taxon .

This classification remained valid for four decades. The different coat patterns of the two subspecies were considered to be an adaptation to local habitat conditions. The brownish coat color of M. p. proboscideus can be traced back to the darker shades of the Karoo, which is also more strongly influenced by shadows. The clearly lighter fur of M. p. flavicaudatus , on the other hand, represented an adaptation to the lighter and sunnier regions of the Namib. Molecular genetic studies carried out at the beginning of the 21st century in combination with field research on site indicated a more differentiated subdivision of the genus Macroscelides . Based on the genetic analyzes, a northern and a southern population could be distinguished, both of which had existed in isolation from one another for a long time. This could also be confirmed by the on-site investigations, which showed that the distribution areas of the two populations in the NamibRand nature reserve are separated by a corridor at least 50 km wide, which prevents contact with one another. The researchers saw it as proven that the northern group with M. p. flavicaudatus and the southern group with M. p. proboscideus is not only to be regarded as a subspecies of a species, but also represents an independent species. Based on these results, the northern subspecies was raised to species status in 2012, making the Namib short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides flavicaudatus ) the second recognized species of the genus Macroscelides alongside the short-eared elephant . Only two years later a third species was established with the Etendeka short-eared elephant ( Macroscelides micus ). This is regionally sympathetic to the Namib short-eared lobbies, but in contrast to this species is characterized by a dark, rust-colored fur.

Tribal history

The tribal history of the Macroscelidea goes back to the Paleocene more than 60 million years ago. In contrast, the genus Macroscelides appeared comparatively late, but in comparison with the closely related elephant shrews ( Elephantulus ) it is represented much less often in the fossil record . The oldest finds are known from the late Pliocene about 3.5 million years ago. Fossil remains from the South African site at Makapansgat are of great importance here . This outstanding site contains the most diverse collection of elephants from southern Africa with more than 250 identified individuals, elephant shrews being by far the most common. The remains found are considered to be accumulations of birds of prey that have accumulated over hundreds or thousands of years. There are remains from Kromdraai that are a little younger at almost 2 million years old. The bones and tooth fragments discovered in both Makapansgat and Kromdraai suggest that animals were on average smaller than today's short-eared elephant and had a shorter snout and lower teeth. They are therefore often assigned to the form Macroscelides proboscideus vagans and thus as a subspecies to the short-eared elephant. Since the teeth also differ in individual features from today's representatives, other researchers see this representative as an independent, now extinct species Macroscelides vagans . Finds from Sterkfontein were reported to be 1.7 million years old, which are 25% larger than the earlier forms and hardly differ from today's short-eared elephant. This representative can still be detected at the site up to the upper areas of the fossil layers, the age of which is around 100,000 years. It is noteworthy that all the fossil remains of Macroscelides found so far come from a region at least 500 km east of the current range, which is why it is difficult to assess a relationship to the current species. Due to the different biogeographical distribution in the geological past, further investigations are therefore necessary in order to enable a more exact systematic allocation of the fossil finds.

In addition to these unambiguous finds of Macroscelides, there are also individual remains that can only be assigned uncertainly and possibly also represent the closely related genus Elephantulus . These include the fossils from the Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa, which are of a Pleistocene age.

Threat and protection

The representatives of the genus Macroscelides are known from a spatially very limited area in southwestern Africa, which is influenced by a dry climate. Despite the assumed low population density, the entire existence of the genus and the individual species are classified as not endangered by the IUCN . No major risk potential is currently known. Locally, especially in the area of river plains, the landscapes could be overprinted by the construction of settlements or the cultivation of areas.

literature

- John P. Dumbacher, Galen B. Rathbun, Timothy O. Osborne, Michael Griffin and Seth J. Eiseb: A new species of round-eared sengi (genus Macroscelides) from Namibia. Journal of Mammalogy 95 (3), 2014, pp. 443-454

- Stephen Heritage: Macroscelididae (Sengis). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2018, pp. 206-234 ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4

- Mike Perrin and Galen B. Rathbun: Macroscelides proboscideus Round-eared Sengi (Round-eared Elephant-shrew). In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume I. Introductory Chapters and Afrotheria. Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp. 277-278

- Galen B. Rathbun: Macroscelides proboscideus (Shaw, 1800) - Round-eared elephant-shrew. In: John D. Skinner and Christian T. Chimimba (Eds.): The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 25-27

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d John P. Dumbacher, Galen B. Rathbun, Timothy O. Osborne, Michael Griffin and Seth J. Eiseb: A new species of round-eared sengi (genus Macroscelides) from Namibia. Journal of Mammalogy 95 (3), 2014, pp. 443-454

- ^ A b c d Galen B. Rathbun: Macroscelides proboscideus (Shaw, 1800) - Round-eared elephant-shrew. In: John D. Skinner and Christian T. Chimimba (Eds.): The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 25-27

- ↑ a b c d Galen B. Rathbun: Why is there discordant diversity in sengi (Mammalia: Afrotheria: Macroscelidea) taxonomy and ecology? African Journal of Ecology 47, 2009, pp. 1-13

- ↑ a b c G. B. Corbet and J. Hanks: A revision of the elephant-shrews, Family Macroscelididae. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Zoology 16, 1968, pp. 47-111

- ↑ a b c d John P. Dumbacher, Galen B. Rathbun, Hanneline A. Smit and Seth J. Eiseb: Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the Round-Eared Sengis or Elephant-Shrews, Genus Macroscelides (Mammalia, Afrotheria, Macroscelidea). Plos ONE 7 (3), 2012, p. E32410

- ↑ a b c d Mike Perrin and Galen B. Rathbun: Macroscelides proboscideus Round-eared Sengi (Round-eared Elephant-shrew). In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume I. Introductory Chapters and Afrotheria. Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp. 277-278

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Stephen Heritage: Macroscelididae (Sengis). In: Don E. Wilson and Russell A. Mittermeier (eds.): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 8: Insectivores, Sloths and Colugos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2018, pp. 206-234 ISBN 978-84-16728-08-4

- ^ A b Massimiliano Scalici and Fabiana Panchetti: Morphological cranial diversity contributes to phylogeny in soft-furred sengis (Afrotheria, Macroscelidea). Zoology 114, 2011, pp. 85-94

- ^ Matthew J. Mason: Structure and function of the mammalian middle ear. I: Large middle ears in small desert mammals. Journal of Anatomy 2015 doi : 10.1111 / joa.12313

- ^ A b Mike Perrin and Galen B. Rathbun: Order Macroscelidea - Sengis (Elephant-shrews). In: Jonathan Kingdon, David Happold, Michael Hoffmann, Thomas Butynski, Meredith Happold and Jan Kalina (eds.): Mammals of Africa Volume I. Introductory Chapters and Afrotheria. Bloomsbury, London, 2013, pp. 258-260

- ^ A b Patricia A. Holroyd: Macroscelidea. In: Lars Werdelin and William Joseph Sanders (eds.): Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. University of California Press, Berkeley, London, New York, 2010, pp. 89-98

- ↑ Jan Ihlau, Friederike Kachel and Ulrich Zeller: Graphical description of the ventral side of a sengi's (Macroscelides proboscideus) skull. Afrotherian Conservation 4, 2006, pp. 11-12

- ↑ a b c Melanie Schubert, Neville Pillay, David O. Ribble and Carsten Schradin: The Round-Eared Sengi and the Evolution of Social Monogamy: Factors that Constrain Males to Live with a Single Female. Ethology 115, 2009, pp. 972-985

- ↑ a b Macroscelides in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015.2. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d E. G. Sauer: On the social behavior of the short-eared elephant shrew Macroscelides proboscideus. Zeitschrift für Mammaliankunde 38, 1973, pp. 65-97

- ↑ Melanie Schubert, Carsten Schradin, Heiko G. Rödel, Neville Pillay and David O. Ribble: Male mate guarding in a socially monogamous mammal, the round-eared sengi: on costs and trade-offs. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 64, 2009, pp. 257-264

- ↑ AS Faurie, ER and MR Dempster Perrin: Footdrumming patterns of southern African elephant-shrews. Mammalia 60 (4), 1996, pp. 567-576

- ↑ Graham IH Kerley: Trophic status of small mammals in the semi-arid Karoo, South Africa. Journal of Zoology 226, 1992, pp. 563-572

- ^ MJ Lawes and MR Perrin: Risk-sensitive foraging behavior of the round-eared elephant shrew (Macroscelides proboscideus). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 37, 1995, pp. 31-37

- ↑ CT Downs: Renal structure, and the effect of an insectivorous diet on urine composition of Southern African Elephant-Shrew species (Macroscelidea). Mammalia 60 (4), 1996, pp. 577-589

- ↑ BG Lovegrove, MJ lawes and L. Roxburgh: Confirmation of plesiomorphic daily torpor in mammals: the round-eared elephant shrew Macroscelides proboscideus (Macroscelidea). Journal of Comparative Physiology 169, 1999, pp. 453-460

- ↑ Lizanne Roxburgh and MR Perrin: Temperature regulation and activity pattern of the Round-eared Elephant shrew (Macroscelides proboscideus. Journal of thermal Biology 19 (1), 1994, pp. 13-20

- ↑ a b Steven Heritage, Houssein Rayaleh, Djama G. Awaleh and Galen B. Rathbun: New records of a lost species and a geographic range expansion for sengis in the Horn of Africa. PeerJ 8, 2020, p. E9652, doi: 10.7717 / peerj.9652

- ↑ a b Hanneline Adri Smit, Bettine Jansen van Vuuren, PCM O'Brien, M. Ferguson-Smith, F. Yang and TJ Robinson: Phylogenetic relationships of elephant-shrews (Afrotheria, Macroscelididae). Journal of Zoology 284, 2011, pp. 133-143

- ^ A b John P. Dumbacher, Elizabeth J. Carlen and Galen B. Rathbun: Petrosaltator gen. Nov., A new genus replacement for the North African sengi Elephantulus rozeti (Macroscelidea; Macroscelididae). Zootaxa 4136 (3), 2016, pp. 567-579

- ↑ Julien Benoit, Nick Crumpton, Samuel Merigeaud and Rodolphe Tabuce: Petrosal and Bony Labyrinth Morphology Supports Paraphyly ofElephantulusWithin Macroscelididae (Mammalia, Afrotheria). Journal of Mammal Evolution 21, 2014, pp. 173-193

- ^ A b Andrew Smith: Contributions to the natural history of South Africa. Zoological Journal of London 4, 1829, pp. 433–444 (pp. 435–436) ( [1] )

- ↑ George Shaw: General Zoology or Systematic Natural History. Volume I Part II. Mammalia. London, 1800, pp. 249–552 (p. 536) ( [2] )

- ^ Andrew Smith: Illustrations of the Zoology of South Africa. Mammalia London, 1839 (Plate 10) ( [3] )

- ↑ Oldfield Thomas and Harold Schwann: The Rudd exploration of South Africa. V. List of mammals obtained by Mr. Grant in the North East Transvaal. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1906, pp. 575-591 ( [4] )

- ↑ Bengt G. Lundholm: Descriptions of new mammals. Annals of the Transvaal Museum 22, 1955, pp. 279-303

- ↑ Jerry J. Hooker and Donald E. Russell: Early Palaeogene Louisinidae (Macroscelidea, Mammalia), their relationships and north European diversity. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 164, 2012, pp. 856-936

- ↑ TN Pocock: Plio-Pleistocene fossil mammalian microfauna of Southern Africa - a preliminary report including description of two new fossil muroid genera (Mammalia: Rodentia). Palaeontologia Africana 26, 1987, pp. 69-91

- ^ DM Avery: The Plio-Pleistocene vegetation and climate of Sterkfontein and Swartkrans, South Africa, based on micromammals. Journal of Human Evolution 41, 2001, pp. 113-132

- ^ A b Patricia A. Holroyd: Past records of Elephantulus and Macroscelides: geographic and taxonomic issues. Afrotherian Conservation 7, 2009, pp. 3-7

- ↑ DM Avery: Pleistocene micromammals from Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa: practical issues. Journal of Archaeological Science 34, 2007, pp. 613-625

Web links

- Macroscelides flavicaudatus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2015 Posted by: Rathbun & Eiseb, 2013. Accessed August 16, 2015.

- Macroscelides Micus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2015 Posted by: Rathbun & Dumbacher, 2013. Accessed August 16, 2015.

- Macroscelides proboscideus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2015 Posted by: Rathbun & Smit-Robinson, 2013. Accessed August 16, 2015.