La Vie (painting)

| La Vie |

|---|

| Pablo Picasso , 1903 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 196.5 x 129.2 cm |

| Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

Link to the picture |

La Vie (German Life ) is a painting by the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso from 1903, created in Barcelona , which is considered to be one of the most expressive works of his Blue Period (1901–1904). The 196.5 × 129.2 cm painting is on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art . It is a gift from the Hanna Foundation in 1945. The title La Vie did not come from the artist, but only came into circulation when the work was sold shortly after its completion.

The painting is listed in Picasso's Catalog raisonné by Christian Zervos : Zervos I 179. Examples of preparatory studies are: Private collection, Zervos XXII 44; Paris, Musée Picasso , MPP 473; Barcelona, Museu Picasso , MPB 101.507; Barcelona, Museu Picasso, MPB 101.508.

description

To the left of the room - a painter's studio in pale blue lighting - stands an almost naked young couple; the woman ( interpreted as Germaine Gargallo ) hugs the man who bears the features of Picasso's late friend Carlos Casagemas . With his left hand he makes a conspicuous gesture towards a woman dressed in a long garment, who is holding a sleeping baby in front of her chest with both arms.

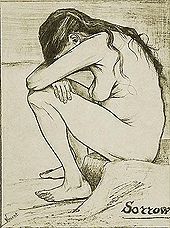

The middle of the picture is dominated by two paintings or sketches as “picture in picture”. The lower, a crouching girl, bears a resemblance to Vincent van Gogh's drawing and three versions of the lithograph composition Sorrow from 1882. X-rays and observations on the original show that instead a much more aggressive motif, namely a winged man with a bird's head, who throws himself on a naked woman lying on the ground with bent legs and arms outspread. The image above is reminiscent of Paul Gauguin in terms of motif and style . It shows a seated couple, apparently clutching each other in desperation. Previous work on the painting has shown that the painter originally depicted himself in the painting and that his friend's portrait took his place after his friend's suicide.

interpretation

It is said that with this programmatic work Picasso was no longer striving for academic standards, but was on the way to the painterly breaks that are clearly recognizable in one of his main works, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907). Obviously, both works are not based on a fixed theme, but rather offer space for the execution of various ideas that cannot easily be combined into a unity in the finished work. The various attempts to interpret this painting have so far not led to any consensus . Picasso himself never commented on the interpretation of this work. The title, which does not go back to Picasso, but appeared shortly after the painting was created, is probably based on the interpretation as a representation of the three ages: childhood, youth and old age, which was also represented by various art scholars. The scene is characterized by a mood of pessimism, despair and suffering, as it was widespread among the youth in Europe at the time. The artist himself was extremely poor at the time.

In view of the puzzling nature of the pictorial content, voices have recently accumulated who refused to commit to a specific interpretation and, in line with Umberto Eco's theory of the open work of art, saw the composition's ambiguity and wealth of associations as a particular strength.

In contrast, the authors Gereon Becht-Jördens and Peter M. Wehmeier wrote about Picasso and Christian Iconography in their 2003 book . Relationship to the mother and artistic self- image describe an iconographic discovery that affects the conspicuous gesture of hand movement in the center of the picture, which can be traced back to the motif Noli me tangere (Don't touch me!) At the meeting of the risen Christ with Mary Magdalene in the garden at the grave. A corresponding work by Antonio da Correggio in the Prado in Madrid, where Picasso had studied, could be identified as the source of the image. The authors regard the painting as a medium for the artist's autobiographical messages, which can be interpreted with the help of depth psychology . Picasso uses the semantics of traditional motifs from Christian art to create his own visual language that becomes a medium of personal communication. In the opinion of the authors, the conflict-laden detachment from the mother represents at the same time a distancing from the traditionalist audience she represents and from a painting art that corresponds to his taste. By resorting to the iconography of Christ, Picasso presented himself to an avant-garde audience as the new messiah in the sense of Friedrich Nietzsche and at the same time justify the suffering that he had to inflict on himself and on his mother through the pain of separation through the promise of salvation, an art of new seeing that liberates from the constraints of reality. In the opinion of the authors, the results of both procedures - iconography and depth psychology - are therefore in no way contradicting each other, but are related to each other and complement each other.

The woman shown in the picture on the right, carrying a baby, is identified by the authors with Picasso's mother following Mary Mathews Gedo. Gedo's interpretation of the central gesture as a gesture of demarcation - the man on the left raises his index finger in the direction of the mother, warning and distancing - is secured by the iconographic discovery. However, Gedo only interpreted the picture in terms of depth psychology, namely as a failed conflict of separation from the mother as an all-controlling supermother, whose presence Picasso could no longer bear. While Gedo sees Picasso's early deceased sister Conchita in the infant and sees a jealousy conflict between siblings connected with feelings of guilt as a topic of discussion, Becht / Wehmeier take the view that Picasso, using the asynchronous representation technique known from Christian art, inserts himself twice in temporally separated situations Image, once as a young man who, hidden behind the mask of his friend Casagemas, decides for his beloved and distances himself from his mother (triangulation), a second time as a divine child (admiration gesture of the covered hands) in a symbiotic dyad united with the mother in her arms. (Iconography of Mary). The discovery of the iconography of Christ lead Becht-Jördens / Wehmeier beyond the depth psychological interpretation to the postulate of a second level of interpretation, on which they work out the self-reflective art-theoretical statement of the composition of La Vie .

Exhibition in Barcelona 2013/2014

For the first time since the painting was created and sold in 1903, it returned to Barcelona from October 2013 to January 2014 and was shown at the Museu Picasso . The exhibition entitled “Viatge a través del blau: La Vida” (Journey through Blue: Life) also showed X-rays of La Vie , which document the state before it was overpainted. The original picture was called Dernier moments (Last Moments). It was exhibited at Picasso's solo exhibition in the artist café Els Quatre Gats in Barcelona in February 1900 and then at the World Exhibition in Paris , also in 1900.

Already in 2006 was La Vie been seen in Madrid: On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the return of the painting Guernica to Spain and to celebrate the 125th birthday Picasso at that time had an exhibition entitled Picasso - Tradition and Avant-garde in the museum Prado occurred .

literature

- Reyes Jiménez de Garnica, Malén Gual (ed.): Journey through the Blue. La Vie. Exhibition catalog Museu Picasso, Barcelona, October 10, 2013 - January 19, 2014. Institut de Cultura de Barcelona: Museu Picasso, Barcelona 2013, ISBN 978-84-9850-496-5 .

- William H. Robinson: Picasso and the Mysteries of Life: La Vie (Cleveland Masterworks). Exhibition catalog Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio 2012/2013. Giles, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-907804-21-2 .

- Johannes M. Fox: Vie, La. In: Johannes M. Fox: Picasso's World. A lexicon . Volume 2, Projekt-Verlag Cornelius, Halle 2008, ISBN 978-3-86634-551-5 , pp. 1297-1299.

- Raquel González-Escribano (Ed.): Picasso - Tradition and Avant-Garde. 25 years with Guernica. Exhibition catalog Museo Nacional del Prado, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, June 6 - 4 September 2006. Museo Nacional del Prado, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid 2006, ISBN 84-8480-092-X , p. 76-83.

- Siegfried Gohr : I don't look, I find. Pablo Picasso - Life and Work. DuMont, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-8321-7743-4 , p. 44 f.

- Gereon Becht-Jördens, Peter M. Wehmeier: 'Touch me not!' A gesture of detachment in Picasso's La Vie as symbol of his self-concept as an artist. In: artnews.org

- Gereon Becht-Jördens, Peter M. Wehmeier: Picasso and Christian Iconography. Mother relationship and artistic self-image . Reimer Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-496-01272-2 , further literature ibid, p. 15, note 13.

- William H. Robinson: The Artist's Studio in La Vie. Theater of Life and Arena of Philosophical Speculation. In: Michael FitzGerald (Ed.): The Artist's Studio (Hartford Catalog, Cleveland 2001). Hartford et al. 2001, pp. 63-87.

- Gereon Becht-Jördens, Peter M. Wehmeier: Noli me tangere! Mother relationship, detachment and artistic positioning in Picasso's Blue Period. On the meaning of Christian iconography in “La Vie”. In: Franz Müller Spahn, Manfred Heuser, Eva Krebs-Roubicek (eds.): The eternal youth. Puer aeternus (German-speaking Society for Art and Psychopathology of Expression, 33rd Annual Conference, Basel 1999). Basel 2000, pp. 76-86.

- Mary Mathews Gedo: The Archeology of a Painting. A Visit to the City of the Dead beneath Picasso's La Vie. In: Mary Mathews Gedo: Looking at Art from the Inside Out. The psychoiconographic Approach to Modern Art . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1994, ISBN 0-521-43407-6 , pp. 87-118.

- Marilyn McCully: Picasso and Casagemas. A matter of life and death. In: Jürgen Glaesemer (Ed.): The young Picasso. Early work and the Blue Period (Catalog Bern 1984). Zurich 1984, pp. 166-176.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Study for La Vie I.

- ↑ Study for La Vie II

- ↑ Study for La Vie III

- ↑ Study for La Vie IV

- ↑ Jack D. Flam: Matisse and Picasso: The Story of Their Rivalry and Friendship . Icon Edition, New York 2003, Westview, Boulder, Co Oxford 2003 ISBN 0-8133-6581-3 , Basic Books, New York 2008 (e-book), ISBN 0-8133-9046-X , p. 3.

- ↑ Marlyn McCully: Picasso and Casagemas. A matter of life and death. In: Jürgen Glaesemer (Ed.): The young Picasso. Early Work and Blue Period (Catalog Bern 1984), Zurich 1984, pp. 166–176.

- ↑ Becht-Jördens, Wehmeier, Picasso and Christian iconography offer an overview of the attempts at interpretation and the statements on interpretability. Mother relationship and artistic position. Reimer, Berlin 2003, pp. 14-17, pp. 44 f., P. 96 f. See Siegfried Gohr: I don't search, I find. DuMont, Cologne 2006, p. 44 f

- ↑ cf. Becht-Jördens, Wehmeier, ibid, pp. 146–148; John Richardson, Picasso. Life and Work, Volume 1 1881–1906. Kindler, Munich 1991, pp. 263-279; Josep Palau i Fabre, Picasso. Childhood and Youth of a Genius 1881–1907, Prestel, Munich 1981, pp. 371–376; Siegfried Gohr: I don't look, I find. DuMont, Cologne 2006, p. 44.

- ↑ Not the Garden of Gethsemane , as the authors write following an error that is also encountered in other literature (p. 40 and more often)!

- ^ Becht-Jördens / Wehmeier: Picasso and the Christian iconography. Reimer Verlag 2003, accessed on March 17, 2009 .

- ^ Mary Mathews Gedo: Picasso, Art as autobiography. University of Chicago Press, 1980, bes, pp. 46-53.

- ↑ Bärbel Küster: Hold me tight! querelles.net, accessed March 17, 2009 . whose criticism is based to a large extent on factually inaccurate assertions.

- ↑ Article on the Museu Picasso website on the exhibition , in English, accessed on June 22, 2019; Reyes Jiménez de Garnica, Malén Gual (ed.): Journey through the Blue. La Vie. (Catalog of the exhibition celebrated at Museu Picasso, Barcelona, october 10th 2013 to january 19th 2014). Institut de Cultura de Barcelona: Museu Picasso, Barcelona 2013, ISBN 978-84-9850-496-5 .

- ↑ See the report on the exhibition in: Kunstaspekte ; Raquel González-Escribano (Ed.): Picasso - Tradition and Avant-Garde. 25 years with Guernica (June 6 - September 4, 2006 Museo Nacional del Prado, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía). Museo Nacional del Prado, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid 2006, ISBN 84-8480-092-X , pp. 76-83.

- ↑ Review: The Cleveland Museum of Art probes the mysteries of Pablo Picasso's “La Vie” in its first special “Focus” exhibition , cleveland.com, December 21, 2012, accessed June 25, 2014.