Lazarillo de Tormes

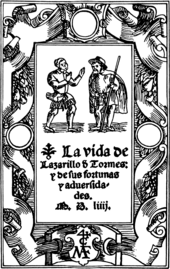

Lazarillo de Tormes is a 1552 anonymous published Spanish novel from which we present only the 1554 printed editions of Burgos, Alcalá, Antwerp and Medina del Campo, and as a precursor of the picaresque novel of European literature history applies. The full Spanish title is La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes y de sus fortunas y adversidades ("The life of little Lazarus of Tormes and his fortunes and adversities").

There are numerous assumptions about the identity of the author. The attribution to Diego Hurtado de Mendoza y Pacheco is controversial, but documents recently discovered by Spanish paleographer Mercedes Agulló seem to support this hypothesis. Numerous verses prove that the latter excelled in picaresque malice.

content

The first-person narrator Lázaro describes his "rise" from poor circumstances in the university town of Salamanca on the Tormes River to the "respectable" post of an urban crier in the Spanish capital of Toledo at the time . With his letter-like narrative, the narrator states in the preface, he wants to convince someone who is unknown to the reader, whom he addresses as Vuestra Merced (Your Grace), to assist him in a dispute. The case is not fully explained, but it turns out that it is about his wedding to a servant of the Archpriest de San Salvador . The priest obviously does not want to dismiss the woman and Lázaro assumes that he is having an unwanted sexual relationship with her.

The novel consists of seven chapters. In the first three chapters, Lázaro describes how as a child he was sent to an apprenticeship by his mother as a servant boy, and how he became more and more hungry with each of his first three masters, even though the social position of his masters grew. First he serves a blind man who teaches him many tricks in begging and cheating. But the blind man wants to give him very little of the food and coins he has stolen. Lázaro can always steal food from him through cunning. His second master is a clergyman who is even more stingy and lets Lázaro almost starve to death. Finally, the third gentleman is an impoverished knight who indulges in honor and knightly virtues without having a proper bed or even enough food for himself and his servant.

In Chapters IV to VI, Lázaro describes his rise in the social hierarchy. Chapters IV and VI each contain only a few pages, in which the Picaro is given the first shoes of his life and finally earns enough money for honest clothing through a job with a chaplain. In the fifth chapter, Lázaro witnesses a deception by his master, an indulgence dealer, against some Pícaros, who are then mocked by him. At the end of the chapter, Lázaro renounces his past once and for all.

In the last chapter, the first-person narrator comes to speak of the case for which he is writing the letter. After a brief description of a few other professional steps, he reports how he is appointed crier at the behest of Archpriest de San Salvador and is offered a house and a wife with whom he actually falls in love. After the wedding, the woman remains the servant of the archpriest and there are rumors in the city (Toledo) that the clergyman has an affair with her. Lázaro describes this time as the happiest of his life, but sums up that he lost his honor during his social advancement in order to gain recognition.

reception

The novel was translated into most Western European languages in the 16th and 17th centuries (the first German-language edition dates from 1617) and enjoyed great popularity, which is partly due to the novel's narrative perspective , which was unusual at the time . The realistic, sometimes drastic and always subliminally humorous depiction of the living conditions of the simple population in the Siglo de Oro stands in sharpest possible contrast to the style of the romanticizing chivalric novels that were popular at the time . The book was immediately banned by the Spanish crown, and the Inquisition put it on the Librorum Prohibitorum Index in 1559 , as both institutions assumed that the novel was anti- clerical . This - not to be dismissed completely - accusation promoted the popularity of the work with its readership. In 1573 the novel was allowed to appear again, but in a censored version from which some sentences were deleted and in which Chapters IV and V were completely missing.

The Lazarillo was not only so successful that it suggested at least two “sequels” penned by other authors, it also founded a literary genre that was picked up across Europe (for example Grimmelshausen's “Simplicissimus” ). The type of " antihero " embodied by Lázaro is an important design element in literature and now also in film.

The novel has left its mark on the Spanish language and culture: certain passages and quotations are still common knowledge today, and in particular the word lazarillo is still used today as a term for a guide dog due to a very popular episode at the beginning of the book . Even Miguel de Cervantes ' novel Don Quixote benefits from the work.

expenditure

- Lazarillo de Tormes / Little Lazarus from Tormes . Spanish German. Translated by Hartmut Köhler. Reclam, Ditzingen 2007, ISBN 3-15-018481-9

- The life of Lazarillo of Tormes. His joys and sorrows. Translated by Michael M. Prechtl. CH Beck, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-406-36476-4

- Life and Change of Lazaril of Tormes . Translated by Manfred Sestendrup. Reclam, Ditzingen, ISBN 3-15-001389-5

- The life of Lazarillo von Tormes, his luck and his misfortune . Transferred by Georg Spranger. With ten woodcuts v. Rudolf Peschel. Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1962. Insel-Bücherei; 706

- The story of the life of Lazarillo de Tormes and his sorrows and joys. Told by himself. With its continuation . Newly translated and edited by Urs Usenbenz. Albert Züst, Bern 1945

Secondary literature

- Bernhard König: (Anonymous) La Vida de Lazarillo de Tormes, y de sus fortunas y adersidades . In: Volker Roloff, Harald Wentzlaff-Eggebert (Ed.): The Spanish novel: from the Middle Ages to the present . Metzler, Stuttgart [a. a.] 19952, pp. 30-46.

Film adaptations

- 1959: The rascal of Salamanca ( El lazarillo de tormes ) by César Fernández Ardavín .

- 2001: Lazaro de Tormes ( Lázaro de Tormes ) by Fernando Fernán Gómez , José Luis García Sánchez .

- 2013: El lazarillo de Tormes by Juanba Berasategi .

- 2015: El lazarillo de Tormes by Pedro Alonso Pablos .

Web links

- Full text and materials in the Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (Spanish), accessed on July 2, 2019.

- Full text in Spanish with German translation . Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- Cartoons about Lazarillo de Tormes. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ News from the author: “Lazarillo de Tormes”. In: Der Umblatter , February 15, 2009.

- ↑ El Lazarillo no es anónimo ( es ) El Mundo (Spain). Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ↑ Antonio Rey Hazas: Deslindes de la Novela Picaresca , Málaga 2003, pp. 43-45.

- ↑ Antonio Rey Hazas: Deslindes de la Novela Picaresca , Málaga 2003, p. 57