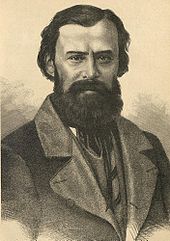

Lev Alexandrovich Mei

Lev Alexandrowitsch Mei ( Russian Лев Алекса́ндрович Мей , February 13th July / February 25th 1822 greg. In Moscow - May 16 July / May 28, 1862 greg. In Saint Petersburg ) was a Russian poet . Four of his historical dramas were chosen by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov as models for operas long after his death , including the Tsar's Bride , which is still widely played today . Many of his poems and adaptations were also set to music by several Russian composers.

life and work

Mei was the son of a Russian woman and a noble officer of German descent who was wounded in the Battle of Borodino in 1812 and died early. He received a state scholarship and was able to attend the imperial lyceum Tsarskoye Selo , like Alexander Pushkin before him . He finished his studies in 1841 and made his living as a civil servant for the next ten years, but was not happy with it. In his free time he studied theology, the classical authors of antiquity and especially old Russian chronicles. In the second half of the 1840s he frequented the literary salon of Mikhail Pogodin (Михаи́л Петро́вич Пого́дин, 1800–1875), a professor of Russian history at Moscow University. From 1841 to 1856, Pogodin was the editor of the scientific and literary journal Moskvitjanin ( Russian Москвитя́нин , German for "The Moscow"), which was considered an organ of the large-scale bourgeoisie and represented patriotic, Slavophile tendencies. Mei started to publish in the magazine. There were two groups within the editorial team, on the one hand the older men, Pogodin, Shevyrev and Weltman, on the other hand the ranks of young writers, mainly represented by Apollon Grigoryev , Alexander Ostrowski and Lev Mei. For a while he tried his hand at high school, but got into conflict with his colleagues.

In 1849 he completed the verse drama Zarskaja nevesta (Царская невеста, The Tsar's Bride), a drama of love and jealousy, in which he describes the omnipotence of Tsar Ivan the Terrible and lets Westerners and Russians argue about the difference in drinking cultures. The historical tragedy in four acts was performed in Moscow in the same year, with considerable success. The audience was impressed both by the authentic atmosphere and by the fresh, natural language found, which clearly set the piece apart from the pseudo-historical melodramas that were played back then.

Lev Mai moved to Saint Petersburg , where he was a literary bohemian , led a dissolute life and married Sofija Grigoryevna Polyanskaya, who from the end of the 1850s ran an important salon and from 1862 published a literary magazine for women, Modnyi Magazine . Mei's wife was forced to earn an independent living, because Mei wrote and translated diligently, but also drank heavily and did not earn enough for a living. From the Saint Petersburg period, among other things, the texts "Heimatliche Notes", "Son of the Fatherland", "Russian Word", "Russian Peace" and "Svetoch" as well as another verse drama, Pskovitjanka (Псковитянка, The girl from Pskov ) came from the year 1860. This piece was also premiered, but was banned by the censors shortly after the premiere. With their dramas, Pushkin and Mei paved the way for the renewal of Russian drama through Ostrowski and Tolstoy .

In particular, the poet translated poetry from many different languages, including Heine , Goethe , Pierre-Jean de Béranger and Lord Byron , the Poles Teofil Lenartowicz , Adam Mickiewicz and Władysław Syrokomla , the Ukrainian Taras Shevchenko . In 1855/56 he completely translated the songs of Anakreon from the original and published a commentary. He also translated the dramas Wallenstein's Camp and Demetrius by Schiller . In his own poetry he also wrote in the strict forms of sonnet , octave and sestine . While his translations were highly praised, especially the translation of Goethe's Only Who Knows Sehnsucht from Wilhelm Meister's apprenticeship years , his own work was heavily criticized in 1860 as “pure art” without taking into account the social situation of the present.

Lew Mei died at the age of only forty, presumably of the consequences of his drunkenness, when a three-volume edition was just being published. He only saw the publication of the first volume.

His name and work were quickly forgotten, but a decade after his death, the Group of Five discovered his work. It turned out that Lew Mei's dramas as well as his poems and adaptations were ideal for setting to music. Nikolai Rimski-Korsakow (1844–1908) chose four of his historical plays as opera models. Mei's lyrical works, both his own and those translated from other languages, have been set to music by a number of Russian composers, including Borodin , Mussorgsky , Rachmaninov and Tchaikovsky .

Four dramas

Three of Mei's four dramas, which Rimsky-Korsakow set to music, focus on young women and marriage plans, mostly of older and powerful men. Ultimately, all of Lew Mei's heroines die tragically or drown in madness, through poison in one case, through a bullet or in a completely unexplained way in the other cases. Differences in class, conceit or power relations always prevent the love of an innocent girl and drive her into misery and death. Servilia is set in ancient Rome, the other two dramas in the time of Ivan the Terrible , who also appears in both operas - in the Tsar's Bride only briefly, incognito and mute, in the Pskov girl in a leading role.

In the fourth drama, which Rimsky-Korsakov set to music , Die Bojarin Vera Scheloga , Ivan the Terrible is once again the focus, without appearing in the play. He seduced and made a married woman pregnant while her husband was away from home. The wife confesses adultery and paternity to her sister, the husband returns and finds the child. The wife threatens to throw herself out the window. To avoid the consequences, the sister declares that she is the mother. The one-act act ends with a lie.

Works set to music

Dramas

By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov were set to music:

- Pskowitjanka ( The girl from Pskov, Russian Псковитянка , 1873)

- Bojarynja Wera Scheloga ( Die Boyarin Wera Scheloga, Russian Боярыня Вера Шелога , 1898)

- Tsarskaja newesta ( The Tsar's Bride, Russian Царская невеста , 1899)

- Servilia ( Russian Сервилия , 1902)

Poems and post-poems

Borodin :

- Sprout from my tears (Из слез моих) (after Heine )

- My songs are poisoned (Отравой полны мои песни) (after Heine )

Angel :

- The canary (Канарейка), op. 1, no. 4th

- Hebrew Song (Еврейская песня)

- Hopak (Гопак, after Shevchenko )

- I wanted to pour out my pains ... (Хотел бы в единое слово, after Heine )

- Children's songs (Детская песенка)

- After mushrooms (По грибы)

- Comment, disaient ‑ ils (Они отвечали, after Victor Hugo )

- Hebrew Song (Еврейская песня), op. 7, no. 3

- Switesjanka (Свитезянка), op. 7, no. 3 (after Mickiewicz )

- Arise, come down! (Встань, сойди!), Op. 8 No. 4th

- Lullaby (Колыбельная песня: "Баю, баюшки баю"), op. 2 no. 2

- Moja pieszczotka (Мойа баловница), op. 42 No. 4 (after Mickiewicz )

- Why are the roses so pale? (Отчего?), Op. 6 No. 5 (after Heine )

- Only those who know longing (Нет, только тот, кто знал), op. 6 no. 6 (after Goethe )

- The canary (Канарейка), op. 25 no. 4th

- I Never Spoke to Her (Я с нею никогда не говорил), op. 25 no. 5

- Ever since they started talking: “Be wise” (Как наладили: “Дурак”), op. 6th

- Evening (Вечер), op. 27 No. 4 (after Shevchenko )

- Was it the Mother Who Bore Me? (Али мать меня роэжала), op. 27 No. 5 (after Lenartowicz )

- Moja pieszczotka (Мойа баловница), op. 27 No. 6 (after Mickiewicz )

- The corals (Корольки), op. 28 No. 2 (after Syrokomla )

- Why (Зачем), op. 28 No. 3

- I wanted to pour out my pain ... (Хотел бы в единое слово) o.op. No. 1 from 1875 (after Heine )

literature

- Reinhard Lauer : History of Russian literature: from 1700 to the present , Munich: Beck 2000, ISBN 3-406-45338-4 , p. 315f.

- Reinhard Lauer : Small history of Russian literature , Munich: Beck 2005, ISBN 3-406-52825-2 , p. 107 and 108.

- Wolfgang Kasack (Ed.): Major works of Russian literature: individual representations and interpretations . Darmstadt: Wiss. Buchges., 1997 (= partial edition of: Kindlers new literature lexicon), p. 217ff.

- Mej, Lev Aleksandrovič , in: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon Online

- Wilfried Schäfer / Karoline Thaidigsmann: Mej, Lev Aleksandrovič: Carskaja nevesta , in: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon Online

- Herbert Oskar Herbst: Studies on Mej's poems . Halle: E. Klinz Buchdruck-Werkstätte, 1941, dissertation Halle 1940 (not viewed)

- Daniel Jaffé: Historical Dictionary of Russian Music , Scarecrow Press 2012, ISBN 978-0-8108-5311-9 , therein Maid of Psykov on pp. 199-200

Web links

- Literature by and about Lev Alexandrowitsch Mei in the bibliographic database WorldCat

- Category: Mey, Lev. In: Petrucci Music Library .

- Author: Lev Aleksandrovich Mey (1822-1862). In: The LiederNet Archive. January 6, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Reinhard Lauer: History of Russian Literature , 2000, p. 315f.

- ↑ a b Klaus Städtke: Poetry around the middle of the 19th century , in: Klaus Städtke (Hrsg.): Russische Literaturgeschichte . 2nd, updated and exp. Ed., Stuttgart: Metzler, 2011, p. 174

- ↑ a b c d e f g Tchaikovsky Research: Lev Mey , accessed on November 14, 2016 (engl.)

- ↑ The dates for the wedding vary between 1850 and 1852.

- ↑ Barbara T. Norton, Jehanne M. Gheith: An Improper Profession: Women, Gender, and Journalism in Late Imperial Russia , therein by Carolyn R. Marks: Provid [ing] Amusement for the Ladies, The Rise of the Russian Women's Magazine in the 1880s, p. 100.

- ^ Petrucci Music Library : Servilia (Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolay) , accessed November 11, 2016.

- ↑ Gerald R. Seaman: Nikolay Andreevich Rimsky-Korsakov: A Research and Information Guide , Second edition, Routledge 2014, ISBN 978-1-315-76177-0 , pp. 10f, 13, 32, 128, 134, 138f, 146 , 410, 583 and 586.

- ^ Dorothea Redepennig: Rimskij-Korsakow, Nicolaj. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Second edition, personal section, volume 14 (Riccati - Schönstein). Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel et al. 2005, ISBN 3-7618-1134-9 , Sp. 138–165 ( online edition , subscription required for full access) (Directory of Stage Works , Sp. 151 f.)

- ↑ Musirony: Nikolai Rimski-Korsakow (1844-1908): Pskovitjanka , accessed on November 12, 2016.

- ↑ Deutschlandradio Kultur : The heroine dead, the city saved - Rimsky-Korsakov's opera "Das Mädchen von Pskow" January 24, 2009, accessed on November 14, 2016.

- ^ Isny Oper (Allgäu): Nikolai Rimski-Korsakow - Arie der Servilia (from the Servilia opera) in the 2015 program, p. 57, accessed on November 12, 2016.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakow: Libretto Boyarinya Vera Sheloga , Stanford University, accessed on November 13, 2016

- ↑ Aleksandr Borodin: Songs and Romances ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Joel Engel: List of works by Joel Engel ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Modest Mussorgsky: Hebrew Song. First version ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Modest Mussorgsky: Child's Song ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Modest Mussorgsky: Desire. Second version ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Modest Mussorgsky: Gathering Mushrooms. First version ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Radio Protocol - Russian Verses as a Melody . ORF.at. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Sergei Rachmaninoff: 12 Romances, Op.21 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov: 6 Romances, Op.8 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov: 4 Romances, Op.2 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov: 4 Romances, Op.42 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov: 4 Romances, Op.7 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Pyotr Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances and Songs, Op.27 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Pyotr Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op.25 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Pyotr Tchaikovsky: Tenor Songs ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Pyotr Tchaikovsky: I Should Like in a Single Word ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Pyotr Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op.28 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Pyotr Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op.6 ( English ) IMSLP. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Richard D. Sylvester: Tchaikovsky's Complete Songs: A Companion With Texts and Translations (Russian Music Studies) X. Indiana University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0253216762 . ( limited preview in Google Book search)

- ^ Karl Laux (ed.), Paul Losse (ed.): Peter Iljitsch Tschaikowsky: Selected songs. Edition Peters.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Mei, Lev Alexandrovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Мей, Лев Алекса́ндрович (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 25, 1822 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Moscow |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 28, 1862 |

| Place of death | St. Petersburg |