Gastric torsion

The torsion of the stomach ( Torsio ventriculi , Dilatatio et Torsio ventriculi ) is a disease in which the stomach rotates around its own longitudinal axis. The cause of the disease is unknown. A stomach torsion occurs mainly in older dogs of large breeds ; small dogs, cats and guinea pigs are rarely affected. The torsion of the stomach manifests itself in an increase in the size of the abdomen, restlessness and unsuccessful attempts to vomit. The expansion of the twisted and gassed stomach quickly leads to a circulatory collapse which , if left untreated , usually leads to the death of the animal. The diagnosis is made using an X-ray. A stomach twist must be treated surgically. After degassing and circulatory stabilization, the abdominal cavity is opened, the stomach is turned back and sewn to the abdominal wall to prevent it from turning again. The mean death rate is around 20 percent. In humans, gastric torsion is a rare disease in infants or a complication after fundoplication and is also known as gastric volvulus .

Origin and occurrence

The stomach (technical language gaster or ventriculus ) is a hollow organ between the esophagus (esophagus) and the duodenum (duodenum) . In an anatomically simplified way, it looks like a larger object that is pulled onto a string and can move freely. When the stomach is rotated, usually clockwise around the longitudinal axis, the gastric entrance is blocked (obstruction) so that air in the stomach can no longer escape by "belching". The air in the stomach is swallowed when eating hastily and / or when turning in a state of anxiety. The assumption that it is fermentation gases has now been refuted. It has not yet been clarified whether the inflation of the stomach is responsible for the rotation or its consequence.

With increasing inflation, the stomach compresses blood vessels (especially the portal vein and the posterior vena cava ) as well as nerve cords and the diaphragm . This increasing insufficient supply of blood leads to a rapid lack of oxygen in all organs and to over- acidification of the blood and leads to a mostly fatal circulatory shock within hours . Spontaneous reverse rotation of the stomach was observed in only a few cases.

The actual cause of the stomach torsion is unknown, just a number of risk factors. Most often, large, deep-rib cage breeds are affected. Among them, some breeds have a particularly high risk of developing the disease. The risk of an animal suffering from a stomach torsion in the course of its life is 30% for Great Danes and Bloodhounds , 20% for large greyhound breeds and collies, and 18% for Irish Wolfhounds . With age and stretched gastric ligaments , the risk of the disease also increases. A stomach torsion occurs very rarely in small dogs, cats and guinea pigs (→ stomach torsion in cats and stomach torsion in guinea pigs ).

All other putative risk factors cannot be clearly proven. Feeding once a day is said to increase the risk of disease, but dividing the daily feed ration into several portions cannot prevent the disease. Increased air swallowing due to hasty food intake has not been confirmed as a risk factor. Contrary to previous recommendations, recent studies suggest that an elevated position of the feed bowl leads to an increased risk.

Clinical symptoms

The typical main symptom is the belly swelling that begins about one to two hours after the last feeding. The animals are restless and sit a lot. Sometimes they try to vomit or defecate. Progressively, the drum-like waist circumference grows very quickly. The “prayer position”, in which the animal holds the front half of its body low, is relatively typical. There is an increasing apathy , which in a shock symptoms passes.

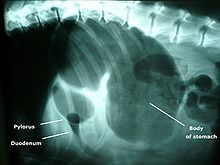

Diagnosis

A reliable diagnosis can be made with an X-ray on the right . As a result of the inflation and displacement of the widening of the gastric outlet ( antrum pyloricum ) - which in the majority of cases occurs to the right, top and front - a fold running from front-bottom to back-top is evident. This phenomenon is also referred to as "compartment formation", it gives the stomach a "whipped hat-like" appearance. In the English-speaking world, this is known as a "double bubble" . If a compartment is formed, a twisting of the stomach can already be reliably differentiated from a simple stomach overload. However, it cannot be observed in the counterclockwise rotation, which is very rare. In the case of an X-ray on the left, compartment formation cannot generally be demonstrated. When positioned on the back, the pyloric antrum, which is usually on the right, presents itself to the left of the midline. Further criteria are a displacement of the intestine and the spleen to the rear and, in some cases, the narrowing of the posterior vena cava (caudal vena cava) at the passage through the diaphragm as a result of shock . In the case of severe and prolonged torsions of the stomach that have already led to the stomach wall dying off, gas can form in the stomach wall ( emphysema ), then the chances of recovery are already poor.

Laboratory diagnostics often reveal impaired blood coagulation and overacidification of the blood .

treatment

The only treatment option is surgical repositioning of the stomach to its normal position. First of all, the dog's circulation must be stabilized by infusions so that an anesthetic can be performed. If the stomach is distended, it is necessary to puncture the stomach to relieve pressure. For this purpose, the organ is pierced through the lateral abdominal wall with a long, wide-lumen cannula.

During the operation, the stomach is first degassed, the stomach contents rinsed out and then the twisting of the organ is reversed. Parts of the stomach wall that have already died are brought into the interior of the organ with an inverted suture. Finally, the stomach is fixed in the abdominal cavity in order to prevent further torsion. This surgery, known as gastropexy , is recommended even in those cases where the stomach has turned back spontaneously. While the relapse rate without gastropexy is around 70%, it drops to around 5% with gastric fixation. Three techniques are currently in use. In incisional gastropexy , the lateral abdominal wall is incised through the transversus abdominis muscle and the stomach wall through the muscle layer to a length of about 5 cm and these two incisions are sewn together. In the belt loop technique , a strip of the stomach wall muscles in the area of the antrum is pulled through a tunnel in the abdominal wall and at its end is sutured back to the stomach wall. In circumcostal gastropexy , this strip is passed around the last rib. Fixations to the large intestine (gastro-colopexy) or by means of a gastric tube have higher recurrence rates and are therefore no longer recommended.

Frequent complications after the operation of a gastric torsion are reperfusion damage , drop in blood pressure , blood clots in the vessels (DIC), acute kidney failure and cardiac arrhythmias , especially ventricular extrasystoles , due to the previous reduced blood flow ( ischemia ) to the stomach wall .

forecast

The results of the therapy depend heavily on the time at which treatment is started. The mortality rate for stomach rotations is on average 20%. If the operation is started up to six hours after the rotation has taken place, there are good prospects for the dog to heal and survive. After that, the survival rate drops significantly. Lactate values in the serum are particularly suitable for estimating the probability of survival . If the lactate value is below 6 mmol / l, the survival rate is 99%. At a value above 7.4 mmol / l, necrosis of the stomach wall can be assumed, at a value above 9 mmol / l the survival rate drops to 55%. The risk of dying of cardiac arrhythmias in the following days after surviving the operation is around 4%.

prevention

Since the actual triggers are not known, prevention is only possible to a limited extent. For large dogs, it is recommended that the daily ration be divided over several meals. The food bowl should be on the floor and excessive movement should be avoided immediately after eating. Some authors recommend a precautionary gastropexy in the context of other abdominal operations, such as the castration of a bitch , for high-risk breeds such as Great Dane or Bloodhound .

Torsion of the stomach in the cat

The torsion of the stomach in cats is similar in clinical picture, diagnosis and treatment to that of dogs, but occurs only very rarely. Diaphragmatic hernias in particular are considered to be a beneficial factor.

Twisting of the stomach in the guinea pig

The cause of gastric torsion in guinea pigs is also unknown. It occurs frequently in breeding animals, but can also occur as a result of repositioning under anesthesia and the use of xylazine . Enlargement of the stomach as a result of the intestinal contents stopping can also lead to stomach rotation. Clinically, the disease manifests itself in exhaustion, inappetence, low temperature and a distended stomach due to the gas-filled stomach and intestine. In contrast to gastric symptoms , the stomach is often shifted to the right side, which can be most reliably represented by a ventro-dorsal X-ray. The therapy is carried out surgically as in dogs, but the prospect of treatment is poor.

literature

- Thomas Spillbaum et al .: gastric dilatation-gastric torsion syndrome ( dilatio et torsio ventriculi) . In: Ernst-Günther Grünbaum and Ernst Schimke (eds.): Clinic of dog diseases . 3. Edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8304-1021-8 , p. 556-560 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Daniel Koch: Twisted stomach in dogs - an overview . In: Small Animal Practice . tape 60 , no. 12 , 2015, p. 652-664 , doi : 10.2377 / 0023-2076-60-652 .

- ^ T. Lawrence et al .: Five-year prospective study of gastric dilatation-volvulus in 11 large and giant dog breeds: non-dietary risk factors , Purdue University, West Lafayette, 2000.

- ↑ a b W. P. Bredal et al .: Acute gastric dilatation in cats: A case series . In: Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica . tape 37 , 1996, pp. 445-451 .

- ↑ a b Judith Wabnitz and Nadja Schneyer: gastric tympany and gastric torsion in guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) - case report . In: Small Animal Medicine . tape 6 , no. 13 , 2013, p. 290-295 .

- ↑ Petra Hellweg and Jürgen Zentek: Risk factors in connection with the dog's stomach twist . In: Small Animal Practice . tape 50 , no. 10 , 2005, pp. 611-620 .

- ↑ Malathi Raghavan et al .: Diet-Related Risk Factors for Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus in Dogs of High-Risk Breeds . In: Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association . tape 40 , 2004, pp. 192-203 .

- ↑ Daniel Koch: Twisted stomach in dogs - an update . In: small animal specifically . tape 13 , no. 5 , 2010, p. 1-5 . (Full text) ( Memento of the original dated February 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Sandra Klein: Torsio ventriculi . In: small animal specifically . tape 10 , no. 2 , 2007, p. 5-13 .

- ↑ Y. Bruchim et al .: Evaluation of lidocaine treatment on frequency of cardia arrhythmias, acute kidney injury, and hospitalization time in dogs with gastric dilatation volvulus . In: J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care . tape 22 , no. 4 , 2012, p. 419-427 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1476-4431.2012.00779.x , PMID 22805421 .

- ↑ LA Zacher et al .: Association between outcome and changes in plasma lactate concentration during presurgical treatment in dogs with gastric dilatation volvulus . In: J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. tape 236 , no. 8 , 2010, p. 892-897 , doi : 10.2460 / javma.236.8.892 , PMID 20392189 .

- ^ L. Formaggini, K. Schmidt and D. De Lorenzi: Gastric dilatation-volvulus associated with diaphragmatic hernia in three cats: clinical presentation, surgical treatment and presumptive aetiology . In: J Feline Med Surg. tape 10 , no. 2 , 2008, p. 198-201 , PMID 18082438 .