Machine from Marly

The Marly machine ( French Machine de Marly ) was the name of two hydraulically driven pumping stations that were used to supply water from the Seine to the water features in the park of Versailles and later in particular those in the park of Marly-le-Roi .

the initial situation

The plans for the Park of Versailles included a large number of fountains and other elaborate water features at an early stage . For the water supply of the Palace Park of Versailles , however, natural springs could not be developed in sufficient quantities, neither on the site itself nor in the surrounding area, which could have supplied the required amounts of water and provided the necessary water pressure to operate the fountains .

Only the course of the Seine north of Versailles offered water in abundance; however, it was nearly five miles from the castle. The real difficulty lay in the fact that the Seine was significantly lower than Versailles. In order to first bring the water from the Seine valley to the surrounding hills and then create a sufficient gradient for it to reach the castle via aqueducts and underground pipes and also to have enough pressure there to operate the fountains, it had to be crossed Pump up 160 meters.

Since renouncing the water features, which are essential for prestige reasons, was out of the question, but on the other hand the already developed water sources were far from sufficient, a mechanical pumping station had to be designed and built that could meet the enormous requirements for the time.

Marly's first machine

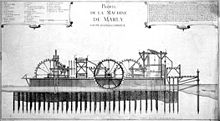

Marly's original machine was built between 1681 and 1684. The plans came from Arnold de Ville and were put into practice by Rennequin Sualem .

The south bank of a bend in the Seine near Marly-le-Roi Castle was chosen as the location . There the river was divided into two arms by a chain of islands. By connecting the islands and a small dam in the southern arm, the water was somewhat dammed in order to have sufficient energy for the operation of the plant. 14 water wheels with a diameter of 12 meters each drove a total of 250 pumps , which carried the Seine water uphill through cast iron pipes in three stages. With the technology at the time, it would not have been possible to overcome the high pressure in order to pump the water directly onto the hill. For this reason, a pumping station with a corresponding intermediate storage was installed above the first and second third of the slope, with which the water was finally pumped into the Louveciennes aqueduct . These pumping stations were driven by the power of the water wheels, which was transmitted via complex rods. The construction of the machine, which was unique at the time, cost the enormous sum of four million livres . In addition to generous payments, Arnold de Ville received the title of Gouverneur à vie de la Machine (chief engineer of the machine for life) and the house on the hillside near the construction site, the Pavillon des Eaux ("water pavilion "), which was built especially for him by order of the king later Château de Madame du Barry .

On June 13, 1684, the completed machine was inaugurated by Marly by Louis XIV and began operation. However, their shortcomings soon became apparent. Even the 14 huge water wheels could not supply Versailles with enough water to keep all water features running. Furthermore, after careful planning, you had to limit yourself to blowing only those fountains that were within sight of the king during the day.

In addition, the huge machine never performed as expected. It was also fragile and often had to be repaired; 60 workers were constantly busy with maintenance. Since it was mostly made of wood that rot from the damp, constant renovation work was necessary, which drove up the maintenance costs. As a result, the conveying capacity fell further, so that the machine was soon only used to supply the Marly-le-Roi castle park.

It was also found annoying that the mechanics of the machine and the drive linkage caused a lot of noise. Almost a hundred years later, Madame du Barry , who had moved into and expanded the former home of Arnold de Ville, complained that at night, when the reservoirs were filled for the following day, she was often unable to sleep because of the deafening noises.

Although Marly's machine was considered a marvel of engineering, admired by numerous visitors to Versailles - including Peter the Great in 1717 and Thomas Jefferson in 1784 - and even described in Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie , interest declined over the course of the 18th century their increasingly expensive preservation. Around 1758 parts of the plant were taken out of service, so that it only worked with reduced performance. Although it was increasingly neglected, especially after the French Revolution , it remained operational - albeit to a limited extent - until 1817. During a visit to Nymphenburg Palace, Napoleon was so impressed by the fountain in the palace park , which was driven by the new pumping stations installed by Joseph von Baader , that he summoned Baader to Paris in 1805 to make suggestions for the technical improvement of Marly's machine . However, his ideas did not come to fruition.

On August 25, 1817, it was finally stopped and demolition began.

Despite the great effort, the performance of Marly's machine and its gigantic water wheels was modest: under optimal conditions, it could only pump 2000 to 2500 cubic meters of water up the slope within 24 hours .

The second machine from Marly

After the extensive dismantling of the old Marly machine, a steam-driven pump system was built in the same place, including some remaining parts , which from 1827 supplied the Versailles park, but also the surrounding communities, with 2000 cubic meters of water per day. The operation was expensive, however, as the steam engines required large quantities of coal for this.

Therefore - caused by Napoléon III. - In 1854 the construction of a new, now again hydraulically operated, pumping station began at the same location. This second Marly machine was designed by the engineer Xavier Du Frayer and was incomparably more powerful than its predecessor from 1684. Six water wheels, each 12 meters in diameter and 4 meters wide, drove the pumps, which were capable of handling 18,000 to 20,000 cubic meters of water per Day pumping uphill from the Seine. During normal operation, 7000 cubic meters of water were raised.

After its inauguration on June 9, 1859, Marly's second machine was in service for over 100 years, but in the end it was only used to generate electricity. On June 20, 1963 it was shut down due to damage and demolished in 1967. The water supply was taken over by electrically operated pumps.

Current condition

No remains of Marly's two machines have survived; however, the water pipes of the younger machine can still be found today. Of the older one, there are some administrative and auxiliary buildings from the 17th century on the banks of the Seine.

literature

- Thomas Brandstetter: Measuring forces. Marly's machine and the culture of technology 1680–1840 , Diss. Weimar 2006, available online as a PDF (8.8 MB) via the document server of the Bauhaus University Weimar .

- Jacques and Monique Lay: Catalog for the exhibition La Machine de Marly , 1998

- Carl Ergang: Marly's machine . In: Conrad Matschoss (ed.): Contributions to the history of technology and industry . Volume 3. Springer, Berlin 1911, ZDB -ID 2238668-3 , pp. 131-146. - Full text online .

- Louis Figuier : Les merveilles de l'Industrie , 1875

- Bernard de Bélidor : Architecture Hydraulique, ou L'art de conduire, d'élever et de ménager les eaux pour les différens besoins de la vie . tape 2 . Charles-Antoine Jombert, Paris 1739, p. 195–203 ( digitized on Gallica ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Château de Madame du Barry, chemin de la Machine, Louveciennes

- ^ Joseph von Baader: Projet d'une nouvelle machine hydraulique pour remplacer l'ancienne machine de Marly suivi de l'apperçu d'un autre moyen de fournir des eaux a la ville et aux jardins de Versailles, sans employer la force motrice de la riviere ; Paris, Renouard, 1806.

Web links

- La Machine de Marly on marlymachine.org (English)

- Les merveilles de l'industrie: La Machine de Marly on voltaweb.elec.free.fr

- La machine de Marly on H2o.net

Coordinates: 48 ° 52 '16 " N , 2 ° 7' 32" E