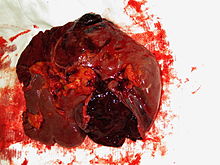

Ruptured spleen

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| S36.0 | Injury to the spleen |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

A rupture of the spleen is an injury (tear) to the spleen , usually caused by blunt abdominal trauma . Spontaneous ruptures of the spleen without trauma are rare and occur in special infectious diseases or haematological diseases that are accompanied by abnormal enlargement of the spleen ( splenomegaly ). The rupture of the spleen is usually treated surgically , but can occasionally be treated conservatively . When possible, organ-preserving therapy is given preference over removal of the spleen .

causes

The most common cause of ruptured spleen is blunt abdominal trauma, e.g. B. in case of work, traffic or sports accidents. A fall on a bicycle or motorcycle handlebar or on a ski pole is typical. A severe blow or kick in the abdominal area can also lead to a ruptured spleen. In patients with multiple injuries, the rupture of the spleen is often the acutely most threatening component of the abdominal injury. As a concomitant injury, there may be broken ribs in the lower left chest area. Direct, perforating injuries, for example from stab or gunshot wounds, are less common. Perforating injuries can also result from the impaling of severely displaced, broken ribs.

Iatrogenic spleen injuries, i.e. injuries caused by medical measures, can occur during major abdominal operations. These are usually superficial tears in the capsule due to pulling on the stomach or the left flexure of the large intestine or bruises due to the use of abdominal hooks .

In addition to traumatic ruptures of the spleen, non-traumatic, so-called spontaneous ruptures of the spleen rarely occur, in which the rapid swelling of the spleen can lead to capsular ruptures with bleeding into the surrounding area. The cause of this are infections, e.g. B. mononucleosis , spleen tumors, e.g. B. malignant lymphomas and angiomas, or portal vein thrombosis into consideration.

Forms and degrees of severity

The parenchyma of the spleen is encased in a delicate connective tissue capsule, which can tear if the force is applied. Even in a healthy spleen, the parenchyma itself is very soft and well supplied with blood. The organ is thus primarily protected from injuries due to its position far back in the abdomen through the stable structures of the spine and the lower ribs.

There are different forms of injury: The pure capsule tear without damaging the parenchyma usually only leads to minor oozing bleeding from the exposed parenchymal surface. If the capsule and parenchyma are torn, the severity of the bleeding depends on the depth of the tear and the simultaneous damage to blood vessels in the spleen. Very severe, acutely life-threatening bleeding occurs in the case of tears in the vicinity of the splenic hilum, i.e. the blood vessels entering the spleen from the tail of the pancreas , in multiple fragmentation of the spleen and in the case of tears in the spleen near the hilum .

In some cases, bleeding from the spleen takes a long time: If the parenchyma does not tear for the time being, an increasing bruise develops inside the capsule ("subcapsular hematoma"). With increasing pressure, the capsule ruptures after days, in extreme cases even after several weeks, and bleeding occurs into the abdomen. In these cases, a two-stage rupture of the spleen is spoken of, and accordingly the rupture of the spleen with immediate bleeding is referred to as a single-stage rupture of the spleen.

Since these different types of injuries have a direct influence on the prognosis and the surgical procedure, five degrees of severity are distinguished:

- Grade 1: capsular tears, subcapsular non-expanding hematoma

- Grade 2: Injury to the capsule and parenchyma without injury to segment arteries

- Grade 3: Injury to the capsule, parenchyma and segmental arteries

- Grade 4: Injury to the capsule, parenchyma and segment or hilar vessels, tear off of the vascular pedicle

- Grade 5: avulsion of the organ in the splenic hilus with devascularization (interruption of the vascular supply)

Symptoms and Diagnosis

The first indication of the presence of a rupture of the spleen often results from the anamnesis : Any blunt injury to the left upper abdomen or the left flank can be accompanied by a rupture of the spleen. In the case of minor injuries with little bleeding, there are unspecific upper abdominal pain, tenderness in the epigastrium , pounding pain in the area of the left flank and left-sided breathing-dependent complaints. Patients often report pain radiating to the left shoulder ( Kehr sign ). The irritation of the diaphragm and thus the phrenic nerve through bleeding or capsular hematoma leads to pain in the left side of the neck ( Saegesser sign ).

In the case of higher degrees of injury with profuse bleeding, the signs of impending or manifest volume deficiency shock come to the fore: Accelerated pulse with low blood pressure ( tachycardia and hypotension ), accelerated breathing ( tachypnea up to hyperventilation ), pale, cold and cold-sweaty skin, fear and restlessness. An increasing clouding of consciousness as a result of the cerebral lack of oxygen forces immediate life-saving measures.

The basic diagnosis of a suspected spleen rupture is the sonography of the abdominal organs. The detection of free fluid is already possible with small amounts, coarser parenchymal injuries of the spleen or large subcapsular hematomas can also be displayed. If the sonographic findings are normal but the clinical suspicion persists, the examination must be repeated closely so as not to overlook a two-stage rupture or an increasing capsular hematoma. X-rays of the chest and abdomen do not provide any further evidence of the presence of a ruptured spleen, but are performed to rule out further injuries (e.g. rib fractures with pneumothorax ). If the circulatory system is stable, a computed tomography of the abdomen can give a more precise overview of the extent of the spleen injury. Peritoneal lavage , which was carried out regularly until the 1990s, is no longer in use because of its high error rate.

Laboratory tests are primarily used to estimate blood loss ( hemoglobin , erythrocyte count , hematocrit ) and the general assessment of organ functions (kidney, liver, etc.). The blood gas analysis provides information about the oxygen saturation of the blood and, if the shock increases, it shows that the blood is acidic ( acidosis ). In the blood count , a ruptured spleen usually shows a high increase in the number of leukocytes .

therapy

The therapeutic approach is primarily determined by the severity of the rupture. While a rupture of the spleen was treated almost exclusively by removing the spleen ( splenectomy ) until the 1980s , the improvement in conservative bleeding control has meanwhile made differentiated therapy possible from the point of view of organ preservation.

First degree ruptures can often be treated conservatively with close monitoring of the sonographic findings, the circulatory parameters and the blood count, as these lesions can close and heal as part of the body's own hemostasis ( hemostasis ). All other degrees of severity require surgical intervention.

The basic aim of the surgical procedure is to preserve the spleen. In severity grades 2 and 3, hemostasis can often be achieved using infrared or electrocoagulation and fibrin glue , and the spleen can also be wrapped in an absorbable plastic mesh and thus compressed. In severity grade 4, partial resection can sometimes preserve a functional part of the spleen, while in grade 5 only a splenectomy is considered.

The selection of the appropriate surgical procedure does not only depend on the severity of the injury. While every effort is made to preserve organs in children and adolescents, splenectomy is more likely to be used in older people. The reason for this is, on the one hand, the lower complication rate ( post-splenectomy syndrome ) in adults and, on the other hand, the frequent accompanying diseases that increase the risk of intra- or post-operative complications in the case of lengthy maintenance attempts with high blood loss. Unfavorable anatomical conditions, such as those that exist in the case of pronounced overweight ( obesity ), can also steer the decision in the direction of a more easily performed splenectomy.

Complications

After organ-preserving therapy, there are usually no specific complications. In the early phase, unspecific surgical complications such as postoperative bleeding, wound infection or thrombosis , possibly with pulmonary embolism, are possible.

Early postoperative complications of splenectomy are primarily respiratory complications: pneumonia , atelectasis , pleural effusions . In about 1–3% of cases, pancreatic fistulas occur as a result of undetected injuries to the pancreatic tail . After splenectomy, it can lead to increased susceptibility to infections, in 1-5% of cases, a dangerous overwhelming post-splenectomy infection , a foudroyant running sepsis come. In addition, patients after splenectomy are more prone to the occurrence of thromboembolic events due to the increasing platelet count .

literature

- Souza-Offtermatt, Staubach and others: Intensive surgery course. Elsevier / Urban and Fischer, Munich 2004, p. 474 ff., ISBN 3-437-43490-X

- JR Siewert, RB Brauer: Basic knowledge of surgery . 2nd Edition. Springer, Berlin - Heidelberg 2010, ISBN 3-642-12379-1 , chap. 7.17 Spleen , p. 330 ff .

- H. Emminger, T. Kia: Exaplan: the compendium of clinical medicine . 6th edition. tape 2 . Urban & Fischer at Elsevier, Stuttgart - Berlin 2009, ISBN 3-437-42463-7 , chap. 28 spleen , p. 547 ff .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c J. R. Siewert: Chirurgie . 7th edition. Springer, Berlin - Heidelberg 2010, ISBN 3-540-30450-9 , 37 Milz , p. 760 ff .

- ↑ D. Reinhard: Therapy of diseases in childhood and adolescence . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin - Heidelberg 2007, ISBN 3-540-71898-2 , chap. 56.9 Splenectomy , p. 709 ( preview on google books [accessed July 27, 2011]).