Brown-headed cowbird

| Brown-headed cowbird | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Brown-headed cowbird male ( Molothrus ater ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Molothrus ater | ||||||||||||

| ( Boddaert , 1783) |

The brown-headed cowbird ( Molothrus ater ) is a songbird from the starling family. It is an obligatory breeding parasite that occurs in North America from the temperate climate zone to the subtropics. It uses an unusually large number of host bird species: It has been proven that 144 songbirds have successfully reared young birds of the brown-headed cowbird.

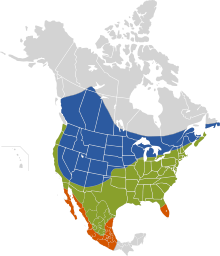

Originally, the brown-headed cowbird was limited in its distribution to the prairie areas grazed by bison , as it is dependent on open areas for foraging. Since the beginning of the colonization of the North American continent by European settlers, it has greatly expanded its range and its population has increased sharply. Today this species is one of the most widespread bird species in North America. It is a very common bird, but the populations have remained constant since the 1960s.

Brown-headed cowbird of the northern distribution area migrate to the southern United States and Mexico in the winter months. They return to their summer areas from March to April.

features

The bird has a short finch-like beak and dark eyes. The male is mainly glossy black with a brown head. The female is gray in color with a lighter breast and a finely dashed underside.

Occurrence

The brown-headed cowbird lives in open and semi-open landscapes in most of North America. While the southern populations are resident birds , the northern populations migrate to the southern United States or Mexico. He flocks, sometimes together with the red-shouldered blackbird and the starling . In the wintering areas it resides in flocks that can include tens of thousands of birds of this species.

In winter, the brown-headed cowbird is also a frequent guest at bird feeders .

behavior

The brown-headed cowbird looks for insects on the ground that are attracted or scared off by grazing animals. Similar to the Eurasian cuckoo , the breeding parasitism of this species allows breeding areas and feeding grounds to be far apart. It is typical that Brown-headed Cowbird spend the morning alone or in pairs during the breeding season in areas with a high density of host birds. In the afternoon they go to their feeding grounds. They find suitable foraging grounds on agricultural land and pasture land. But they also seek out suburbs where lawns offer them food.

There is usually only a distance of one to seven kilometers between the feeding grounds and the breeding grounds. There are, however, other extremes: A single horse pasture in California's Sierra Nevada offers brown-headed cow sterling a suitable feeding area. However, this single pasture allows brown-headed blackbirds to parasitize host birds in an area of 154 square kilometers.

Reproduction

The brown-headed cowbird is a breeding parasite that lays its eggs in the nests of other small songbirds, especially in shell nests such as those of the golden wood warbler . The young brown-headed cowbird are fed by the host parents at the expense of their own offspring.

Migrating brown-headed cowbird return to their breeding areas between the end of March and the beginning of May. On their northward migration, they are often associated with red-shouldered blackbirds and purple glaciers . The egg-laying period begins in April at the earliest and ends around July. At this point in time, the brown-headed cowsterlings again form large swarms and then set off for the wintering areas.

Breeding area and pair bond

Basically, the size and exclusivity of the breeding area used by a female of the brown-headed cowbird vary with the population density of both brown-headed cow sterling and that of the host bird. Basically, females compete for host bird nests while the males compete for the females.

The breeding areas that females occupy and also defend vary greatly. In the Sierra Nevada, a single female uses an average breeding area of 68 hectares. A songbird of the same weight that raises its young birds itself normally uses a breeding area of one to three hectares. Because a single female cannot successfully defend such a large breeding area, such large breeding areas usually overlap. In regions with a higher density of host bird species, the breeding areas are significantly smaller. Different brood area sizes were found in different studies. The breeding areas in New York State were between 10 and 33 hectares, while in another study in Ontario they were between eight and ten hectares. Areas of this size are vigorously defended by the female. The male they mated with vigorously defends this area against all other males.

In areas with a very high density of brown-headed cow sterling, there is no close bond between males and females. Brown-headed cowbird no longer behave monogamous in these areas, but both females and males mate with several partners.

Host bird species

The number of host bird species is very high: a total of brown-headed cowbird eggs were found in the nests of 220 different species. 144 species of them have successfully reared young birds of this species. Most of them feed their young birds with invertebrates, a diet on which the nestlings of the brown-headed cowbird also depend. Host species range from just 6 grams heavy mosquito catchers weighing up to 100 grams Lerchenstärlingen . With their body weight of 40 to 50 grams, some of the host bird species correspond to that of the brown-headed cowbird. Most, however, are smaller. In sum, the host bird species comprise the majority of North American songbirds.

Finding the host bird's nest and laying eggs

As with many other brood parasitic species, the female first monitors and observes the nests of potential host bird species and chooses the nest before laying the egg in it. The female occasionally sits for a long time in bushes or on trees and looks for nest building activities. In the absence of such waiting areas, the female walks on the ground and observes the surroundings from there after such activities. The female also flies up briefly in dense vegetation and then lands on stalks with loud flapping of wings in order to induce potential host bird species to fly up from their nests.

The eggs are usually laid when the host bird is also in the process of completing its clutch. Similar to brood parasitic cuckoos, the female destroys eggs and injures or kills young birds when the host bird's breeding activities are too advanced. As a rule, the loss of such a clutch is followed by a second clutch by the host bird, which gives the brown-headed cowbird the opportunity to lay its egg in the clutch at the right time.

Degree of parasitization

Compared to brood parasitic species such as the cuckoo , not only is the number of host bird species in the brown-headed cowbird exceptionally high, but also the degree of parasitization. This is due to the fact that brown-headed cowbird have a much higher population density than cuckoos usually do. In the Great Plains region , where brown-headed cowbirds are most numerous, the degree of parasitism in numerous host bird species is between 20 and 80 percent. Populations of the golden warbler near the Canadian Manitoba Lake, for example, showed a parasitic degree of 21 percent by the brown-headed cowbird over a period of 12 years. In contrast, a study carried out in Kansas found a parasitic degree of 70 percent in the case of Dickzissel , grasshopper and larkbird , all three of which breed on the ground. Other examples of species that breed in regions with a high population density of brown-headed cowbird, for example, have a paratization rate of 24 percent for the white-bellied phoe beast , 76 percent for the red-shouldered blackbird , 52 percent for the swarming bark and 69 percent for the roach vireo .

The degree of parasitization is particularly high where only a few fragmented forest areas are surrounded by agricultural pastureland or arable land. In these regions, for example, the forest thrush shows a degree of parasitization of up to 100 percent. The number of eggs in the nest of the forest thrush is also high in these areas: Often in these nests there are as many eggs from brown-headed cowbirds as from forest thrushes, since several of these brood parasites lay an egg in these nests. NB Davies points out that the reasons why the degree of parasitization is particularly high in regions with fragmented forest areas is not yet fully understood: What plays a role, however, is that the adjacent agricultural areas provide the brown-headed blackbird with numerous feeding grounds and transitions between two different habitats offer attractive nesting opportunities for a number of host bird species, so that brown-headed cowbird concentrate primarily on these transitions when they are looking for suitable host nests. Finally, these transitions can also offer the brown-headed cowbird more suitable cover from which it can observe host birds.

In regions where the brown-headed cowbird is a migratory bird, host bird species have the chance that they can raise at least their first clutch without parasitization. A study in Washington State showed that blackbirds that brood at the beginning of May only had a parasitic degree of 7 percent. In the case of representatives of this species who then began to breed, the degree of parasitization rose to 50 percent.

The brown-headed cowbird can lay up to 36 eggs a year. When the foreign eggs are recognized by the host parents, they react in different ways. The cat thrush pecks the eggs. Other birds build a new nest over the old one. Sometimes the hatched brown-headed cowbird are thrown from the nest.

Investigations by Jeffrey Hoover and Scott Robinson have shown that the brown-headed cowbird in half the cases the nests of lemon warbler destroyed if he refuses to raise the foreign offspring. If the lemon warbler had previously successfully defended itself against the egg-laying parasites in its own nest, the nests were completely spared.

Distribution history

Before European colonization, the brown-headed cowbird was rare east of the Mississippi . Since bison were rare or not present at all, the extensive open areas that were created by bison grazing and on which the brown-headed cowsterling relies were missing. An indication that it was unknown to the first settlers is its lack in Carl von Linné's Systema Naturae from 1758, where the red-shouldered blackbird and the crimson blackbird were listed as typical North American birds, but the brown-headed cowbird was missing.

The brown-headed cow sterling began to spread rapidly on the North American continent in the 18th century. It was preceded by a gradual development of the eastern part of North America until the first settlers reached the easternmost foothills of the Great Plains . NB Davies speaks of “corridors” of short-grass pastureland that the first farmers created with their pigs, cattle and sheep, through which the brown-headed cowbird, which was previously restricted to the Great Plains, was able to advance further east, where the long-standing European colonization meanwhile unites Habitat had created from agricultural areas, pastures and fragmented forests, which corresponded to the habitat requirements of the brown-headed cow sterling. As early as 1790, the brown-headed cowbird was often found in individual populated regions in the east of the USA. At that time there were around four million settlers in North America, part of the country was already being farmed in the 6th generation.

With increasing population density and thus increasing animal husbandry, the number of brown-headed cow sterling also increased. Towards the end of the 19th century, the brown-headed cow sterling was a consistently common bird in eastern North America. It is very likely that this species had very high reproduction rates at the time, so that increasing population density forced the birds to develop new ranges. For the 20th century, more precise data are available on the spread. In the 20th century in Ontario , a province in southeastern Canada, the northern limit of distribution of the species shifted 300 kilometers further north. Nova Scotia was colonized by this species in the 1930s and Newfoundland in the 1950s. The brown-headed cowbird appeared in Florida and Georgia from the 1950s on, and in the 1960s it also opened up to Alabama as a further distribution area.

In western North America, the historical distribution area of the brown-headed cowbird extended to the Rocky Mountains . In the southwest it occurred in Arizona along the Colorado River and was possibly represented as far as Texas. From there, the brown-headed cowbird spread in California from the beginning of the 20th century. The distribution took place very quickly: In 1955 the species first appeared in the Canadian province of British Columbia . Overall, the species managed to expand its range 1,600 kilometers further north within a few decades. Once again, the decisive factor was an increasing expansion of agricultural areas and a fragmentation of the forest in this region. In parts of the region, the brown-headed cowbird is one of the most common breeding birds today.

Trivia

The American ornithologist Herbert Friedmann has dealt with the brown-headed cowbird for almost 70 years. The knowledge about the breeding parasitism of this species can be traced back to him and his colleagues, who examined the host bird species and the breeding success in extensive field studies.

literature

- NB Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats . T & AD Poyser, London 2000, ISBN 0-85661-135-2 .

Web links

- Videos, photos, and sound recordings of Molothrus ater in the Internet Bird Collection

- Molothrus ater in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on December 18 of 2008.

- Strong offs use Mafia methods , Article in the World , March 6, 2007 (accessed August 4, 2012)

Single receipts

- ↑ a b c d e f g Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 145.

- ↑ Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 141.

- ↑ Henninger, WF: A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio . In: Wilson Bulletin . 18, No. 2, 1906, pp. 47-60.

- ↑ a b c d e f Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 146.

- ↑ a b c d Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 147.

- ↑ a b Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 148.

- ↑ a b c d e Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 143.

- ↑ a b Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 144.