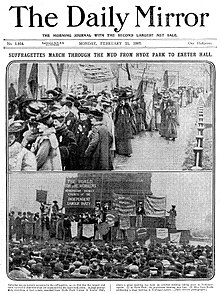

Mud March (Suffragettes)

The United Procession of Women of 1907, also known as the Mud March , was a peaceful demonstration on 9 February in London , organized by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and attended by more than three thousand women from Hyde Park to Strand marched to promote women's suffrage and held a rally at Exeter Hall. Women from all walks of life took part in the largest public rally for women's suffrage ever seen in the UK(UK) had given. The United Procession was named the Mud March because of the weather; because in heavy rain, the protesters ended up soaked and spattered with mud.

The march failed in its aim of directly influencing Parliament. However, he did have a significant impact on the public profile and future tactics of the women's suffrage movement. Marches became important elements of suffrage campaigns. They also showed that women from all walks of life, across all social differences, supported the fight for the right to vote.

prehistory

In the UK in 1907 women suffrage advocates were divided into two main movements, the 'suffragists', who wanted to use constitutional methods, and those who advocated more immediate action, later dubbed 'suffragettes'. From October 1897 there was the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), led by Millicent Fawcett , which was the leading organization with a constitutional leaning and wished to ally with sympathetic MPs to achieve its goal. From 1903, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), founded and formed by Emmeline Pankhurst , existed, i.e. the suffragettes , who tended to attract public attention, wanted to mess with the representatives of the people, advocated violence against things and would rather go to prison demonstratively than a punishment for to pay for their offenses (such as smashing windows).

In 1907 the relationship between these two movements was still cordial and friendly, as the suffragettes had not yet begun to destroy other people's property. When eleven suffragettes were imprisoned in October 1906 following a protest in the lobby of the House of Commons, Fawcett and the NUWSS supported them.

A month after the overwhelming victory of Henry Campbell-Bannerman 's Liberal Party in the 1906 general election , WSPU suffragettes held a successful demonstration march of 300 to 400 women in London because the Prime Minister had declared that a women's suffrage bill was unrealistic . To show that there was further support for a Suffrage Act, it was proposed by the Central Society for Women's Suffrage in November 1906 that a large demonstration be held in London to coincide with the opening of Parliament in February. The NUWSS and other groups called on their members to participate. The event attracted a lot of public interest and also received friendly support from the press.

Demonstration in rain and mud

organization

The organization of the “Procession of Women” had been entrusted to Pippa Strachey. Although inexperienced, she carried out the task so successfully that she was later put in charge of planning all the major NUWSS marches.

Regional women's rights societies and other organizations were invited to take part in the large-scale demonstration. Efforts were made to appease any political disagreements and sensitivities so that all groups would attend. Around forty organizations from all over the country took part. The march was to begin in Hyde Park and proceed via Piccadilly to Exeter Hall, a large meeting hall on the Strand . A second outdoor gathering was planned for Trafalgar Square . Members of the Artists' Suffrage League produced posters and postcards for it.

Demonstration march on February 9th

On the morning of February 9, a large number of women gathered at the starting point of the march, Wellington Arch near Hyde Park Corner. Between three and four thousand women gathered, women of all ages and walks of life, in dreadful weather with torrential rain. Fawcett wrote that "mud, mud, mud" was the main hallmark of that day. In addition to noble demonstrators, there were a number of working women, doctors, school teachers, artists and large contingents of workers from northern and other provincial towns. They marched under banners emphasizing their different trades, such as weavers, cigar makers, clay pipe workers, shirt makers, and machine weavers.

Although the WSPU was not officially represented, many of its members attended, including Christabel Pankhurst , Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence , Annie Kenney, Anne Cobden-Sanderson , Nellie Martel, Edith How-Martyn , Flora Drummond , Charlotte Despard , and Gertrude Ansell. According to historian Diane Atkinson , it was common to belong to both organizations, to attend each other's events and to wear both clubs' insignia.

By 2:30 p.m., the march had positioned itself well into the park's "Rotton Row." It started in the pouring rain, with a brass band leading the way and Lady Frances Balfour, Millicent Fawcett and Lady Jane Strachey at the head of the marching column. The procession was followed by a long line of carriages and automobiles, many bearing the letters "WS", red and white banners and bouquets of red and white flowers. Despite the weather, thousands of curious people thronged the sidewalks to see the novel spectacle, which saw respectable women demonstrating in the streets. The reaction of the viewers was of course quite different, depending on which class and which social class they belonged to.

rallies

On reaching Trafalgar Square, the procession parted: representatives of the northern industrial cities stopped at Nelson 's Column for an open-air event prepared by the Northern Franchise Demonstration Committee. The main procession continued the march to Exeter Hall for a meeting to be held there, chaired by Liberal politician Walter McLaren, whose wife, Eva McLaren, was also one of the scheduled speakers.

Keir Hardie , the leader of the Labor Party , told the gathering (to hisses from several Liberal women on the podium) that if women won the right to vote it would be thanks to the 'Suffragette Fighting Brigade'. He strongly endorsed the assembly's resolution, which was passed, that women should be given the right to vote on the same basis as men, and he called for a bill to be introduced in the current session of Parliament.

At the Trafalgar Square gathering, Eva Gore-Booth spoke on the "alienation of the Labor Party through the action of a certain section in the suffrage movement," according to The Observer newspaper by the action of a certain section of the women's rights movement) and asked the party "not to punish the millions of women workers" because of the action of a small minority. Hardie, returning from Exeter Hall, expressed the hope that "no working man bring discredit on the class to which he belonged by denying to women those political rights which their fathers had won for them". disgrace his class by denying women the political rights their fathers would have won for them").

effects

failure in Parliament

The event drew a lot of public interest and had wide and friendly press coverage. But when the bill - tabled by Willoughby Dickinson - was introduced the following month, it was "talked out" by filibuster speeches without even being put to a vote.

press echo

As one commentator noted, newspaper coverage of the women's movement in one week gave it more publicity than it had received in the past fifty years.

In its lead article, The Observer warned that "the vital civic duty and natural function of women ... is the healthy propagation of race" and that the aim of the movement was "nothing less than complete sex emancipation". (German: "that the vital civil duty and natural function of women ... is the healthy reproduction of the human race" and that the goal of the movement is "nothing less than the complete emancipation of the female sex".)

The day after the march in the same article, The Observer also farsightedly stated:

"The right of women not only to vote, but to enter public life on equal conditions with men. It is a physical problem before all things, and an economic problem of great complexity and difficulty. ... It is the fact that women are not educated to take any rational interest in politics, history, economics, science, philosophy or the serious side of life, which they, as the embodiment of the lighter side, are brought up, and have been brought up since the days of Edenic beginnings, to consider as the privilege and property of the stronger sex. The small section of women who desire the vote completely ignore the educational feature of the whole question, as they do the natural laws of physical force and the teachings of history about men and government."

(German: "The right of women not only to vote, but also to enter public life under equal conditions with men. It is first of all a physical problem and a very complex and difficult one. ... It is a fact that women are not brought up to have any reasonable interest in politics, history, economics, science, philosophy or the serious side of life, all of which they regard as the prerogative and possession of the stronger sex, since they are seen as the embodiment of the lighter side of the and has been so since the beginning of mankind.The small group of women who desire the right to vote completely ignore the educational problem of the whole question, as they do with the natural law of physical power and the teachings the story about men and domination.")

aftermath

While the march did not affect the immediate legislative process, it did have a significant impact on public awareness and future tactics of the women's movement. Large, peaceful, public demonstrations, never attempted before, became standard tools of the suffrage campaign; on June 21, 1908, up to half a million people attended Women's Sunday , a WSPU rally in Hyde Park. These marches showed that the struggle for women's suffrage had the support of women from every walk of life who, despite their social differences, were able to unite and work together for a common cause.

Embracing this activism brought the Constitutionalists' tactics closer to those of the WSPU, at least when it came to nonviolent activities. In her 1988 study of the suffrage campaign, Tickner observes that "modest and uncertain as it was by subsequent standards, [the march] established the precedent of large-scale processions, carefully ordered and publicised, accompanied by banners, bands and the colors of the participant Societies." (English: "As modest and vague as it was by later standards, [the march] set a paradigm for large-scale demonstrations, carefully directed and publicized by banners, bands, and the colors of the participating associations were accompanied.")

From 1907 until the start of World War I, the NUWSS and the suffragettes held several peaceful demonstrations. On June 13, 1908, over 10,000 women in London took part in a procession organized by the NUWSS, and on June 21 of the same year the aforementioned Women's Sunday was held in Hyde Park. During the NUWSS Great Pilgrimage Star March of April 1913, women from all parts of the country marched to London to take part in a mass event in Hyde Park and 50,000 attended.

The failure of the Voting Rights Act proposal brought about a change in the strategy of the NUWSS; the association began to intervene directly in by-elections, on behalf of whatever party's candidate publicly supported women's suffrage. In 1907 the NUWSS supported the Conservatives in the Hexham constituency and the Labor Party in the Jarrow area. Where no suitable candidate was available, they used the by-election to advertise. In the eyes of the NUWSS, this tactic worked sufficiently well for them to decide that they would continue to fight in all future by-elections. And between 1907 and 1909 they were involved in 31 by-elections.

glass window

The Mud March is depicted on Window No. 4 of the Stained-glass Dearsley Windows in St Stephen's Hall at the Palace of Westminster . The window contains sections depicting the formation of the NUWSS, WSPU, and Women's Freedom League , the NUWSS Great Pilgrimage , the force-feeding of the suffragettes, the Cat and Mouse Act , and the death (1913) of Emily Davison , among others . The window was installed in 2002 as a memorial to the long and eventually successful struggle for women's suffrage.

See also

- Women's Sunday

- Great pilgrimage

- Woman Suffrage Procession , in the US (1913)

literature

- Diane Atkinson: Rise Up, Women! The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes . Bloomsbury, London 2018.

- Jane Chapman: Gender, Citizenship and Newspapers: Historical and Transnational Perspectives . Palgrave Macmillan, London 2013, ISBN 978-1-137-31459-8 .

- Krista Cowman: Women in British Politics, 1689-1979 . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2010.

- Elizabeth Crawford: The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866–1928 . UCL Press, London 2003, ISBN 1-135-43402-6 .

- Elizabeth Crawford (ed.): Campaigning for the vote: Kate Parry Frye's suffrage diary . Francis Boutle Publishers, London 2013, ISBN 978-1-903427-75-0 .

- Patricia Fara: A Lab of One's Own: Science and Suffrage in the First World War . Oxford University Press, London 2018, ISBN 978-0-19-879498-1 .

- Millicent Fawcett: What I Remember . Putnam, New York 1925.

- Lucinda Hawksley: March, Women, March . Andre Deutsch, London 2017, ISBN 978-0-233-00525-6 .

- Leslie Hill: Suffragettes Invented Performance Art. In: Jane de Gay, Lizabeth Goodman (eds): The Routledge Reader in Politics and Performance. Routledge, London 2002, ISBN 1-134-68666-8 , pp. 150–156.

- Sandra Stanley Holton: Feminism and Democracy: Women's Suffrage and Reform Politics in Britain, 1900-1918 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003.

- Leslie P. Hume: The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies 1897–1914 . Routledge, London 2016, ISBN 978-1-317-21327-7 .

- Homer Lawrence Morris: Parliamentary Franchise Reform in England From 1885 to 1918 . Columbia University, New York 1921, OCLC 1002391306 .

- Sylvia Pankhurst: The Suffragette: The History of the Women's Militant Suffrage Movement . Sturgis & Walton Company, New York 1911, OCLC 66118841 .

- June Purvis: Christabel Pankhurst: A Biography . Routledge, London/New York 2018.

- Antonia Raeburn: The Militant Suffragettes . New English Library, London 1974, OCLC 969887384 .

- Harold L. Smith: The British Women's Suffrage Campaign 1866-1928. 2nd Edition. Routledge, London 2014, ISBN 978-1-317-86225-3 .

- Ray Strachey: The Cause: a Short History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain . Bell and Sons, London 1928, OCLC 1017441120 .

- Lisa Tickner: The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907–14 . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1988, ISBN 0-226-80245-0 .

- Lisa Tickner: Banners and Banner-Making. In: Vanessa R. Schwartz, Jeannene Przyblyski (eds.): The Nineteenth-century Visual Culture Reader. Routledge London 2004, ISBN 0-415-30866-6 .

web links

itemizations

- ↑ Hawksley, 2017, p. 64.

- ↑ "Founding of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies", UK Parliament

- ↑ Holton, 2008.

- ↑ "Suffragists or suffragettes", BBC

- ↑ In January 1906, the Daily Mail coined the term suffragettes for members of the WSPU; they accepted the label with pride.

- ↑ "Suffragists or suffragettes", BBC

- ↑ Crawford, 2003, p. 452.

- ↑ Cowman, 2010, p. 65.

- ↑ Tickner, 1988, p. 74.

- ↑ Hume, 2016, p. 32.

- ↑ Caine, 2004.

- ↑ Hill, 2002, p. 154.

- ↑ Smith, 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Crawford, 2003, p. 438.

- ↑ Fawcett, 1925, p. 190.

- ↑ Crawford, 2003, pp. 30, 98, 159 and 250

- ↑ Tickner, 1988, p. 75, citing the Tribune

- ↑ The Observer , "Titled Demonstrators" ("The Procession"), February 10, 1907.

- ↑ Atkinson, 2018, p. 60.

- ↑ The Observer , "Titled Demonstrators," February 10, 1907.

- ↑ The Sphere , February 16, 1907.

- ↑ Atkinson, 2018, p. 60.

- ↑ Hume, 2016, p. 34.

- ↑ Tickner, 1988, p. 121.

- ↑ Tickner, 2004, p. 347.

- ↑ Smith, 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ The Observer , "Titled Demonstrators" ("Mr Hardie's Speech"), February 10, 1907.

- ↑ Tickner, 1988, p. 75.

- ↑ Crawford, Elizabeth: "Kate Frye's Suffrage Diary"

- ↑ Atkinson, 2018, p. 60.

- ↑ Pankhurst, 1911, p. 135.

- ↑ Crawford, 2003, p. 273.

- ↑ Daily Mail , February 11, 1907.

- ↑ The Observer , "Titled Demonstrators" ("Mr Hardie's Speech"), February 10, 1907.

- ↑ Pankhurst, 1911, p. 135.

- ↑ Tickner, 1988, p. 78.

- ↑ Hume, 2016, p. 38.

- ↑ Crawford, 2003, p. 438.