Neuroethics

The Neuroethics ( English neuro ethics ) is a discipline in the border area between the neuroscience and philosophy .

There is still disagreement in research on the subject of neuroethics. Some scholars see neuroethics as that part of bioethics that deals with the moral evaluation of neuroscientific technologies . William Safire (1929–2009) defined neuroethics as “the area of philosophy that morally discusses the treatment or improvement of the human brain.” Typical questions of neuroethics understood in this way are: To what extent can one intervene in the brain to avoid diseases to heal or improve cognitive skills such as attention or memory ?

However, most researchers use the term neuroethics in a broader sense. For them, the relationship between neuroscientific knowledge and morally relevant concepts such as “responsibility”, “freedom”, “rationality” or “personality” is also at the center of neuroethical considerations. The neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga understands the term neuroethics as "the social questions about illness, normality, mortality, lifestyle and the philosophy of life, informed by our understanding of the basic brain mechanisms". The basic idea of the EFEC developed by Jorge Moll is to explain the emergence of moral sensation from the combination of structured event knowledge , socially perceptive and functional properties as well as central states of motivation. Neuroethics defined in this way ultimately asks about the significance of brain research for human self-understanding.

While the term neuroethics has already found widespread use in neuroscience, it does not only meet with approval in philosophy. Many questions in neuroethics have long been a topic of general philosophy. This applies, for example, to the question of the relationship between scientific knowledge and human self-image and also to the debate about technical interventions in “human nature”. Therefore, the need for a “neuroethics” discipline is sometimes contested.

Overview

A wide variety of research programs are summarized under the term neuroethics. From the philosopher Adina Roskies of Dartmouth College , the distinction between a native ethics of neuroscience and neuroscience of ethics .

Neuroscience ethics

The ethics of neuroscience is a philosophical discipline that asks about the moral-philosophical relevance of neuroscientific results. One can again distinguish between applied and general ethics in neuroscience:

The applied ethics of the neurosciences questions specific technologies and research projects. One example is the use of imaging techniques . Is it legitimate to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data to track down lies ? In fact, there are already commercial companies in the US that promise fMRI-based lie detection . Such projects, however, are classified as dubious by respected neuroscientists.

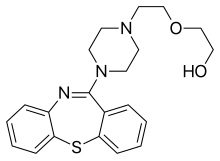

Other important areas of application can be found in neurochemistry . It is possible to selectively change the activity of the brain using pharmacological substances. A well-known example are neuroleptics , which are used to treat psychotic and other mental disorders . Another example that has been widely discussed in public is the use of methylphenidate , which is taken by around one to two percent of all US school children to calm down and increase concentration. The not undisputed methylphenidate is said to help children with attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder . Applied neuroethics asks to what extent such interventions are morally justified and when, in turn, socio-educational , psychotherapeutic , soteria , meditation , pastoral care and similar concepts are to be considered more ethical. Such questions are becoming increasingly explosive, as neuropharmacological substances are now often used beyond the narrow medical framework.

The general ethics of neuroscience , on the other hand, examines the role neuroscientific results play for the general self-image of moral subjects. According to the majority accepted view, free will is a prerequisite for the moral evaluation of actions. The neurosciences, however, regard the brain as a system that is completely determined by its previous states and the input . In general neuroethics, the question is how these ideas fit together. Similar problems arise from terms such as “person”, “responsibility”, “guilt” or “rationality”. All of these terms play a central role in the moral and ethical consideration of people. At the same time, however, they have no place in the description of neural dynamics by brain research . General neuroethics essentially deals with a topic that was formulated and discussed in the philosophy of David Hume and Immanuel Kant in all sharpness: people can be viewed as biological, determined systems and as free, self-responsible beings. How can you counter this apparent contradiction?

One concession on the part of some neurobiologists is the pre- frontal cortex's pre-eminent role in moral decision-making.

Neuroscience of Ethics

The neuroscience of ethics is concerned with the study of brain processes that are associated ( correlate ) with morally significant thoughts, sensations, or judgments . For example, it can be asked what happens in the brain when people have morally relevant sensations or when cognitive access to these sensations can be demonstrated. Such studies are initially purely descriptive .

In contrast, ethics is a normative discipline, it tests what should be . This has led to the objection that it is misleading to discuss the results of empirical work under the term neuroethics. As a descriptive discipline, the neuroscience of ethics is not itself part of ethics.

This is countered by the fact that the neuroscientific results are nevertheless important for ethical debates. It is stated that it would be a naturalistic fallacy to infer normative statements from descriptive statements alone. Knowing how the world is (descriptive) is not enough to provide clues as to how the world should be (normative). However, the descriptive premises are assigned a crucial role in any moral argument. This results in a moral-philosophical meaning of neuroscientific findings. Accordingly, the ethical evaluation of a person will look very different if, for example, one learns that they have a brain lesion that makes empathy impossible. According to many researchers, such examples show that neuroscientific findings can play a central role in the moral or even legal evaluation of actions. In addition, neuroscience is able to provide knowledge about the connection between sensations, rational thinking and motivation to act.

history

Neuroethics has not long existed as an independent discipline. However, some of the neuroethical questions are of older origin. This applies above all to the question of the relationship between the moral-psychological and biological description of humans. David Hume and Immanuel Kant already discussed the apparent contradiction that humans are, on the one hand, a free, self-responsible individual and, on the other hand, a biological system that is determined by strict natural laws . Hume believed that this contradiction only existed superficially and that both descriptions are ultimately compatible. Kant reacted to this problem with a two-world doctrine: He argued that humans are determined systems only in the world of appearances, while speaking of determining natural laws in the world of things in themselves makes no sense. Since, according to Kant, no reliable statements can be made beyond the phenomena, the idea of free will remains an ideal to which one should orient oneself.

Many questions in applied neuroethics, however, are of more recent origin. This is due to the fact that most neurotechnologies were only developed in the second half of the 20th century. However, experiments were carried out as early as the 1950s and 1960s that obviously needed a neuroethical discussion. The bioethicist Arthur Caplan describes, for example, CIA experiments with LSD that were aimed at controlling states of consciousness in animals and humans. Such applications of neuronally active substances are a classic topic in neuroethics.

Institutionally, however, neuroethics has only developed in recent years. Of particular importance here was a conference on neuroethics held in San Francisco in 2002. At this conference, the term neuroethics was popularized, and the conference contributions resulted in the first book entitled Neuroethics . Since then, the topic has developed rapidly. Neuroethics is currently discussed mainly by neuroscientists and less by philosophers. Well-known neuroscientists working in the field of neuroethics include Nobel Prize winners Eric Kandel , Martha Farah , Michael Gazzaniga , Howard Gardner, and Judy Illes . However, neuroethics is also discussed by philosophers such as Patricia Churchland and Thomas Metzinger . The Neuroethics Imaging Group at Stanford University is of institutional importance . In 2006 the Society for Neuroethics was also founded.

General neuroethics

The personal and the sub-personal level

Central to the classification of neuroethics is the distinction between two levels of description. On the one hand, people can be grasped as psychological beings with desires, feelings and beliefs, and on the other hand, as biological systems. Daniel Dennett specifies this difference by speaking of a personal and a subpersonal perspective. It is obvious that the morally relevant vocabulary is on the personal level. They are people who are free to act, responsible or guilty of. In contrast, neuroscientific descriptions take place on a subpersonal level, on which moral evaluations have no meaning. It would be pointless to say that some neural activity is responsible or guilty.

For neuroethics, the crucial question is how the relationship between the personal and subpersonal levels is to be thought. Does the progress on the subpersonal level mean that personal (and thus moral) descriptions must increasingly be rejected as wrong? Most philosophers answer this question in the negative. This applies regardless of the metaphysical positions - physicalists , dualists and representatives of other positions usually agree on this. Only eliminative materialists claim that the personal description of man is wrong and should be completely replaced by an appropriate neuroscientific description. Ultimately, such philosophers postulate that the morality known to us should be replaced by a neuroscientifically informed procedure or should be completely abolished.

Among the critics of eliminative materialism, the concrete ideas about the relationship between the two levels differ significantly. Dualists believe that the concepts of the personal level refer to an immaterial mind , while the concepts of the subpersonal level refer to the material brain. Accordingly, the two levels are not connected with each other, since statements refer to different areas of reality . Contemporary philosophers are often monists and reject the dualistic idea of two completely different areas of reality. This monism can take the form of reductionism . Reductionists argue that the personal level can ultimately be explained by the subpersonal level. Other representatives of monism, however, claim that the two levels of description are equivalent perspectives that cannot be traced back to one another. They often use the analogy of a tilted image : some images can be viewed from different perspectives and can therefore have very different characteristics. In the same way, people should be viewed from a personal and a sub-personal perspective, none of these perspectives is actually the fundamental one.

Free will

The impression of a general conflict between the personal-moral and the sub-personal-neuroscientific level quickly arises in the debate about free will . The moral evaluation of actions presupposes a certain freedom of the acting person. This is also reflected in criminal law under the subject of incapacity . According to Section 20 of the Criminal Code , a person cannot be punished if he has been driven to act by a disorder of consciousness. The idea behind this is that the person in question did not freely choose to commit the act, for example because they lacked the necessary ability to think rationally or because they were driven by an uncontrollable delusion . This legislation appears or really conflicts with recent neuroscientific knowledge.

Most neuroscientists view all human actions as products of neural processes that are determined by the previous biological states and the input . All actions are therefore determined within the framework of physical, scientifically explainable processes and can not happen otherwise. The world is ordered by strict laws of nature , a state of the world is determined by its previous state. In addition, neuroscientists point out that they can currently at least roughly assign a biological fact to every action with imaging methods: When a person hits a blow, for example, certain activities in the brain can be observed. Signals are sent from the brain to the muscles that ultimately realize the blow. According to most neuroscientists, “free will” has no meaning in this sequence of biological causes, rather the action can only be described using scientifically explainable processes. Some neuroscientists, however, posit that laws and their enforcement are necessary for human society.

A fundamental objection to the thesis that free will is a human-scientific construct without reference to reality is the question of responsibility for individual actions when all actions can be explained by physical processes. Often it can be heard from other areas of science that the postulates of neuroscientists themselves are based on metaphysical and thus unprovable assumptions and can be assigned to scientific determinism . A moral assessment of acts presupposes a more or less limited free will or at least the solution of the contradiction between the personal-moral and the sub-personal-neuroscientific description. The interpretation of the results of the neurosciences as evidence against the existence of individual responsibility is opposed to the thesis of differently determined personal-moral conditions.

In Germany, the neuroscientists Wolf Singer and Gerhard Roth in particular have argued that their research results on the brain as the sole factor in human activity must lead to the abandonment of the idea of free will. Such a position has a tremendous impact on the concept of ethics . If the idea of freedom were to be rejected, people could not determine their own will. They could therefore no longer be held responsible for their actions, moral judgments and emotions would no longer make sense. The legally significant distinction between free and unfree acts would also be omitted. Ultimately, one should treat all perpetrators as incapable of guilt. In contrast, the statement z. B. Singers, in the interest of the general public, criminals could be locked up and treated, but no guilt could be determined, and the idea of punishment, although necessary, is incoherent .

There are several strategies for dealing with this problem. Most philosophers take a position which they call " compatibilism " in their technical language . Compatibilists argue that the contradiction between free will and determinism only exists superficially and disappears on closer inspection. The central error is therefore the identification of freedom with the lack of any determination. Such a conception is self-contradicting: if one's own will were not determined by anything , the will would not be free, but simply accidental. “To be free” cannot therefore mean “to be fixed by nothing”. Rather, what matters is what limits the will. One direction of the compatibilists takes the view that man is free exactly when his own will is determined by his own thoughts and convictions. On the other hand, he is unfree whose will formation is independent of his convictions. This idea can be illustrated by a simple example: A smoker is unfree precisely when he is convinced that he should stop smoking and still reach for cigarettes again and again. Such a situation can provoke the oppressive feeling of bondage, and it is clear that the smoker's freedom would not lie in the complete limitlessness of his actions. Rather, the smoker would be free precisely if his convictions had his will under control and he would no longer light up new cigarettes. Such a concept resolves the conflict between freedom and determinism. In the context of compatibilism there is therefore no contradiction between the moral and the neuroscientific level of description. Most contemporary philosophers are compatibilists, well-known representatives are Harry Frankfurt , Daniel Dennett and Peter Bieri .

In a way, David Hume can also be considered the father of compatibilism. He was of the opinion that freedom of will and limitation of the human being through character traits, convictions and desires - based on sensory impressions - can be reconciled. Free actions are based on the ability to make different decisions, depending on the psychological disposition.

Not all philosophers agree with the compatibilist answer to the problem of free will. They insist that the idea of freedom can only be understood when the will and action are not determined by physical processes. Representatives of such a position are called " incompatibilists " in philosophical terminology .

Among the incompatibilities one can again distinguish between two camps. On the one hand, there are philosophers and natural scientists who give up the idea of free will (see above). Other theorists stick to the idea of free will but abandon the concept of determinism. Important representatives of this position are Peter van Inwagen , Karl Popper and John Carew Eccles . Popper and Eccles argue that a brain state is not determined by the previous brain state and input. As a reason they state that what happens on the subatomic level is not determined. According to Popper and Eccles, an immaterial spirit has an influence on physical events on this subatomic level, which can only be described using quantum mechanics. In this working of the spirit the free, unlimited will shows itself.

Applied Neuroethics

Neuro-enhancement

Under the keyword "neuro-enhancement" ( enhancement = English for " increase " and " improvement "), a bitter debate is being waged about whether it is legitimate to improve cognitive and emotional abilities with the help of drugs or neurotechnologies. Proponents of enhancement technologies point out that such procedures are already established in the medical context and are also necessary. The use of neuroleptics represents a direct intervention in the neuronal activity of the patient. Nevertheless, such an intervention is advantageous in the case of psychoses , since it opens up new possibilities for the patient to act. Advocates of "enhancement technologies" now argue that improvements in neurotechnologies are increasingly possible even in healthy people. Why shouldn't people be given the option of higher concentration if appropriate neurotechnological interventions have no side effects ?

At this point, critics argue that a distinction must be made between therapeutic and non-therapeutic interventions. It is justified to use neurotechnologies to help people with illnesses or disabilities. However, there is no reason to “perfect” people through technology. There are two replies to this from the technology optimists: On the one hand, they argue that the distinction between therapy and enhancement is fuzzy. On the other hand, it is stated that the rejection of technological improvements in cognitive abilities is ultimately incoherent . So every education or every mental training has the goal of increasing cognitive or emotional abilities, and ultimately, through the changes that learning undoubtedly causes in the brain, is also an intervention in the neural function of the body. If one advocates such practices, however, one cannot generally vote against neurotechnological improvements.

Current meta-studies such as a study commissioned by the German Bundestag show that there is hardly any evidence of specific performance-enhancing effects in the enhancement preparations available today.

Furthermore, opponents of the human enhancement movement point out that - just like with the concept of health - it is impossible to define independently of cultural ideas which interventions in human nature lead to an improvement and which do not. Especially on cosmetic surgery , this phenomenon is easy to see, see also Bodyismus . Proponents of enhancement technologies see exactly here a starting point, in that they reverse this argument and apply it to the rejection of body modifications . According to him, it is just as questionable because it is obviously impossible to determine how a person should ideally be. However, some representatives of enhancement technologies contradict this statement and explain that one can distinguish between alleged improvements ("fake enhancement") and real improvements (e.g. interventions in the brain in Parkinson's patients).

Opponents of enhancement technologies also fear that optimizing people, in line with social constraints, only leads to increased uniformity and adaptation to social or economic norms. Not only cosmetic surgery is an example of this, work-support drugs also belong in this area. For example, new studies show that at some US universities, 25% of students with neurally active substances reduce their sleep time and increase the workforce. In particular, irreversible enhancements would pose a great risk to people's freedom and independence from economic and political rulers. In this context, however, it should also be borne in mind that participation in a society's system of rule requires certain intellectual qualities, such as a high level of intelligence , which not everyone has by nature, and that biological differences contribute to a large extent to social inequality and poverty . A right to state-sponsored enhancements could help here. Similar to education, it is also true for improving technologies that they could only be financed by part of society itself and that, if state redistribution were not carried out, they would exacerbate existing social injustice .

With regard to the criticism of enhancements, the question finally arises as to whether it makes sense to criticize a technology that allows social norms to be met. Should the standards, the fulfillment of which is sought, be faulty, they would have to be criticized directly. If, on the other hand, the norms are appropriate, the criticism of adaptation to social norms is obviously untenable. It is also completely unclear whether enhancement technologies might rather pluralise the physical and neurobiological characteristics of the population.

In addition, enhancement technologies are a medical risk and, like any complex system, are prone to errors. Its long-term physical effects cannot always be assessed.

Finally, another problem of cognitive enhancement is raised by critics. With the increasing introduction of biological interventions that change the psyche, the personal level of description is being displaced by the subpersonal level. However, this means the gradual decline of all aspects of the personal level that were previously considered important, such as the ideas of self-determination and responsibility. Enhancement advocates, on the other hand, consider it a prerequisite for self-determination and responsibility that a person exercises control over his or her neurobiology. For this, however, the technologies they have in mind are absolutely necessary. The neuroethical dispute over interventions in the brain is therefore still completely unsolved. However, the participants in the debate agree that the topic will become enormously topical and explosive in the coming years and decades.

Strong proponents of enhancement technologies are often supporters of transhumanism .

Imaging procedures

Imaging methods enable the visualization of neural processes in the human brain and represent central methods of neuroscientific research. The development of such methods began in the 1920s with electroencephalography (EEG). Electrical activities of the brain lead to voltage fluctuations on the head surface, which can be recorded by appropriate devices. Today's cognitive neuroscience is particularly based on the method of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). At the same time, these practices raise a number of ethical problems. With the help of fMRI, activities in the brain can be measured with a very high spatial and temporal resolution. This technique leads to ethical problems in particular when at least roughly neural correlates of states of consciousness are found. How do you deal with knowing through neuroscientific methods rather than personal reports that a person is thinking or feeling something?

A classic example is the neurotechnological lie detector . Corresponding fMRI technologies are still in development, but commercial EEG-based lie detectors have been around for a long time. The Brain Fingerprinting Laboratories commercialize such technologies and state that they are used by the FBI , the US police force, and other organizations.

Many neuroethicists are faced with a dilemma with technologies of this kind : On the one hand, appropriate lie detectors in court could save innocent people from imprisonment. On the other hand, it is often argued that such technologies violate people's self-determination and are also prone to abuse .

In addition, the corresponding technologies are not completely reliable. Judy Illes and colleagues at Stanford University's Neuroethics Imaging Group point out the suggestive power of fMRI images, which often obscure the specific problems of data analysis .

The well-known fMRI images (see, for example, figure) have always been largely determined by interpretations . In the case of cognitive performance, the brain is always active over a wide area, but the fMRI images only show the selection of supposedly relevant activities. Such a selection is made using the subtraction method : if you are interested in a cognitive performance K, you measure the brain activity in a situation S1 in which K is required. In addition, the brain activity is measured in a control situation S2, which differs from S1 only in that K is not required in S2. Finally, subtract the activities in S2 from the activities in S1 to see which activities are specific to K. Illes emphasizes that such interpretative aspects must always be taken into account, which can easily be overlooked in court, for example, since lawyers are neuroscientific laypeople.

Turhan Canli explains: “The image of an activation pattern based on a poorly done study is visually indistinguishable from the image of an exemplary study. It takes a skilled professional to tell the difference. There is therefore a great risk of the data from imaging procedures being misused in front of an untrained audience, such as the jury in criminal proceedings. When you look at the pictures, it's easy to forget that they represent statistical inferences and not absolute truths. "

Another problem arises from the expansion of the use of imaging methods. As personality traits or preferences are extracted from brain scans , imaging techniques become attractive for broad commercial applications. Canli discusses the example of the labor market and explains: “There is already literature on personality traits such as extraversion and neuroticism , perseverance, moral processing and cooperation. It is therefore only a matter of time before employers try to use these results for questions about recruitment. ”The advertising industry will also try to use the results of research with imaging methods, because these methods also register unconscious information processing. US consumer organizations have now discovered this issue and are opposed to the commercial expansion of imaging techniques.

Neuroscience of Ethics

overview

An empirical project in the narrower sense is the search for neural correlates of morally relevant thoughts or sensations. Typical research questions can be: What specific activities does thinking about moral dilemmas lead to? What is the functional connection between neural correlates of moral sensations and moral thoughts? What influence do what damage to the brain have on the ability to make moral decisions?

Such questions initially have a purely empirical character and have no normative consequences. The direct conclusion from descriptive documentation of neural activities to normative instructions for action would be a naturalistic fallacy , which is also accepted by most researchers. Nevertheless, the position is often taken that the relevant scientific knowledge could be of great use for ethical debates. On the one hand, neuroscientific research would lead to a new understanding of how people de facto decide moral problems. On the other hand, neuroscientific findings can change moral evaluation in specific situations. A person who is no longer capable of empathy due to brain damage will be judged morally differently than a healthy person. A classic case study for such damage is presented below.

A case study: Phineas Gage

The tragic fate of Phineas Gage is one of the most famous cases in neuropsychology . As a railroad worker, Gage suffered severe brain damage in an accident. The neuroscientist António Damásio describes the situation as follows: “The iron rod enters through Gage's left cheek, pierces the base of the skull, crosses the front part of the brain and emerges from the roof of the skull at high speed. The pole falls down at a distance of more than thirty meters. "

More astonishing than this accident, however, are the consequences. Despite the gruesome injuries and destruction of part of his brain, Gage did not die, he did not even pass out. After less than two months, he was considered cured. He had no problems with speaking, rational thinking, or memory . Still, Gage had changed profoundly. His doctor, John Harlow, explains that he is now “moody, disrespectful, sometimes cursing in the most hideous ways that used to be out of his habit, shows little respect for others, is impatient to restrictions and advice.” Gage had retained his intellectual capacities , but lost his emotional abilities. One of the consequences of this was that Gage no longer acted according to moral standards.

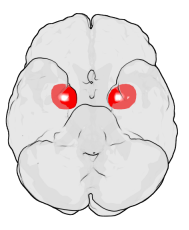

Recent neuroscientific studies have made it possible to pinpoint Gage's brain damage more precisely. The metal rod had partially destroyed the prefrontal cortex ; H. the part of the cerebral cortex that is closest to the forehead. In this case, only the ventromedial part of the prefrontal cortex was damaged - see illustration. Neuropsychological studies have shown that Gage was not an isolated incident. All patients who have a disorder in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex show that loss of emotional faculties while maintaining intellectual abilities.

See also: Theory of Somatic Markers

Importance of Neuroscientific Research

However, it is not only the ventromedial prefrontal cortex that is relevant for moral decisions. As has been emphasized by various quarters, there is no “moral center” in the brain. Rather, moral decisions arise from a complex interplay of emotions and thoughts. And even for moral emotions it is true that they depend on different regions of the brain. An important region is the amygdala , which is not part of the cerebral cortex, but rather the deeper (subcortical) area of the brain. Damage to this area leads to a loss of emotional abilities.

Neuroethically, such results can be reflected in a number of ways. On the one hand, the question of the moral and legal responsibility of such people must be asked. Does the anatomically conditioned inability to moral thoughts and emotions mean that even after a crime has been committed, the person concerned must be treated as a patient and not as a perpetrator? Would you have to send people like Phineas Gage to a psychiatric clinic instead of jail after a crime? If you answer these questions in the affirmative, you have to determine the extent of the disorder from which a corresponding limitation of the culpability should be made. After all, many violent criminals exhibit neurophysiologically detectable brain abnormalities. These could possibly have arisen as a result of repeated immoral thoughts and emotions.

However, neuroscientific studies can also provide insight into the general mechanisms of moral judgment. For example, Adina Roskies tries to use neuropsychological data to prove the thesis that moral emotions are not a necessary condition for moral judgments. She relies on patients with damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex - that is, the damage that Phineas Gage also had. Corresponding individuals lack moral emotions, and they often act cruelly in everyday life, but their judgments about moral issues largely correspond to those of healthy people. Roskies argues that one can ultimately only understand the judgments of such patients as originally moral judgments, and describes her position as a moral-philosophical cognitivism : Although moral emotions may strongly influence moral judgments in everyday life, they are not a necessary requirement.

literature

- Helmut Fink, Rainer Rosenzweig (eds.): Artificial senses, doped brain. Mentis, Paderborn 2010.

- Sabine Müller, Ariana Zaracko, Dominik Groß, Dagmar Schmitz: Opportunities and Risks in Neuroscience. Lehmanns Media, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86541-326-0 .

- Dominik Groß, Sabine Müller (Ed.): Are the thoughts free? The neurosciences past and present. Medical Scientific Publishing Company, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-939069-24-9 .

- Jan-Hendrik Heinrichs: Neuroethics: An Introduction . Metzler, Stuttgart 2019, ISBN 978-3-476-04726-7 .

- Leonhard Hennen, Reinhard Grünwald, Christoph Revermann, Arnold Sauter: Insights and interventions in the brain. The Neuroscience Challenge to Society. Edition Sigma, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-8360-8124-5 .

- Steven Marcus: Neuroethics: Mapping the Field. Dana Press, New York 2002, ISBN 0-9723830-0-X . (Anthology with contributions from a neuroethics conference in San Francisco, which was central to the development of the neuroethics discipline.)

- Judy Illes (Ed.): Neuroethics: defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-856721-9 . (Anthology with articles by many important representatives of neuroethics.)

- Frank Ochmann: The perceived morality. Why we can distinguish good and bad. Ullstein, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-550-08698-4 .

- Carsten Könneker (Ed.): Who explains people? Brain researchers, psychologists and philosophers in dialogue. Fischer TB Verlag, Frankfurt 2006, ISBN 3-596-17331-0 . (Collected volume with contributions by Thomas Metzinger, Wolf Singer, Eberhard Schockenhoff, among others; Chapter 6: Neuroethics and the Image of Man, pp. 207–283.)

- Roland Kipke: Getting better. An ethical study of self-formation and neuro-enhancement , mentis, Paderborn 2011.

- Martha Farah : Neuroethics: the practical and the philosophical. In: Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005, Issue 1, January 2005, pp. 34–40.

- Thomas Metzinger : On the way to a new image of man. In: Brain & Mind. 11/2005, pp. 50-54.

- Thomas Metzinger: The price of self-knowledge. In: Brain & Mind. 7-8 / 2006, pp. 42-49 ( online ).

- Stephan Schleim , Christina Aus der Au : Self-knowledge has its price (replica). In: Brain & Mind ( Online ).

- Stephan Schleim: The neuro-society: How brain research challenges law and morality. Heise Verlag, Hannover 2011, ISBN 978-3-936931-67-9 . (Critical analysis of far-reaching statements on the moral and legal implications of brain research as well as theoretical reflection on brain imaging research.)

- Rüdiger Vaas : Brave new neuro-world. The Future of the Brain - Interventions, Explanations and Ethics. Hirzel, Stuttgart 2008. ISBN 978-3777615387

Web links

- Adina Roskies: Neuroethics. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Neuroethics . Web portal of the Philosophical Seminar of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz

- Overview page on neuroethics by Martha Farah

- Neuroethics Society website

- Website of the Neuroethics Imaging Group in Stanford

Individual evidence

- ^ Judy Illes (ed.): Neuroethics: defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-856721-9 , p.

- ↑ Michael Gazzaniga : The ethical brain. Dana Press New York, 2005, ISBN 1-932594-01-9 , pp.

- ↑ Jorge Moll, Roland Zahn, Ricardo de Oliveira-Souza, Frank Krueger & Jordan Grafman: The event – feature – emotion complex framework , in Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6 , 799–809 (October 2005)

- ↑ Changeux, J.-P .; Damasio, AR; Singer, W .; Christen, Y. (Eds.): Neurobiology of Human Values , 2005, ISBN 978-3-540-26253-4

- ^ Adina Roskies: Neuroethics for the new millennium . In: Neuron , 2002, pp. 21-23, PMID 12123605 .

- ↑ No Lie MRI and Cephos .

- ↑ Editorial. In: Nature 441, 2006, p. 907.

- ↑ Peter Jensen, Lori Kettle, Margaret T. Roper, Michael T. Sloan, Mina K. Dulcan, Christina Hoven, Hector R. Bird, Jose J. Bauermeister, and Jennifer D. Payne. Are stimulants overprescribed? Treatment of ADHD in four US communities. In: Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 1999, pp. 797-804, PMID 10405496 .

- ↑ Popular Science article on this on welt.de .

- ^ Jean-Pierre Changeux , Paul Ricœur : What makes us think? A neuroscientist and a philosopher argue about ethics, human nature, and the brain. Princeton University Press, Chichester 2002, ISBN 0-691-09285-0 .

- ↑ António Damásio : Descartes' error: feeling, thinking and the human brain. German Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-30587-8 .

- ^ Judy Illes (ed.): Neuroethics: defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-856721-9 , p. Vii.

- ^ Steven Marcus: Neuroethics: mapping the field. Dana Press, New York 2002, ISBN 0-9723830-0-X .

- ^ Neuroethics Imaging Group, Stanford .

- ^ Neuroethics Society .

- ^ Daniel Dennett: Content and Consciousness . Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1969, ISBN 0-7100-6512-4 .

- ↑ "is without guilt, who while committing the offense is due to a pathological mental disorder, because of a profound disturbance of consciousness or because of mental retardation or serious other mental abnormality unable to see the injustice of the act or to act according to this understanding." Penal Code Section 20 .

- ↑ This argument is discussed in detail in: Peter Bieri : The craft of freedom. About discovering your own will. Hanser, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-596-15647-5 .

- ↑ Erik Parens: Enhancing human traits: ethical and social implications. Georgetown University Press, Washington DC 1998, ISBN 0-87840-703-0 .

- ↑ nature : Towards responsible use of cognitive-enhancing drugs by the healthy . December 7, 2008.

- ↑ a b All these arguments are e.g. B. discussed in: Erik Parens: Creativity, graditude, and the enhancement debate. In: Judy Illes (ed.): Neuroethics: defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-856721-9 .

- ^ TAB, Office for Technology Assessment at the German Bundestag. Pharmacological interventions to improve performance as a social challenge . Berlin 2011, PDF

- ↑ Martha Farah: Unpublished previous day at the 10th conference of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness in June 2006 in Oxford.

- ^ Judy Illes, Eric Racine and Matthew Kirschen: A picture is worth 1000 words, but which 1000? . In: Judy Illes (ed.): Neuroethics: defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-856721-9 .

- ↑ Turhan Canli , Zenab Amin: Neuroimaging of emotional and personality: Scientific evidence and ethical considerations . In: Brain and Cognition , 2002, pp. 414-431, PMID 12480487 .

- ↑ Turhan Canli: When genes and brains unite: ethical implications of genomic neuroimaging . In: Judy Illes (ed.): Neuroethics: defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-856721-9 .

- ↑ For example Commercial Alert .

- ↑ António Damásio : Descartes' error: feeling, thinking and the human brain. German Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-30587-8 , p. 29.

- ↑ António Damásio : Descartes' error: feeling, thinking and the human brain. German Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-30587-8 , p. 31.

- ↑ William Casebeer, Patricia Churchland : The neural mechanisms of moral cognition: A multiple aspect approach to moral judgment and decision making . In: Philosophy and Biology , 2003, pp. 169-194.

- ↑ a b Adina Roskies: A case study of neuroethics: The nature of moral judgment . In: Judy Illes (ed.): Neuroethics: defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-856721-9 .

- ↑ Adina Roskies: Are ethical judgment intrinsically motivational? Lessons from acquired 'sociopathy' . In: Philosophical Psychology , 2003, pp. 51-66.