Northern Territories of the Gold Coast

The Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (Engl. Northern Territories of the Gold Coast ) was a British protectorate in the northern part of present-day Ghana , which from 1897 until the independence of Ghana in 1957 as an independent part of the British colony of Gold Coast has existed. The protectorate was created primarily to have a legal basis that justifies taking violent action against the pirate armies of a Samory Touré and a Babatu dan Isa operating in the hinterland of Ashanti , but also at the same time to avoid areas in the Occupy the Gold Coast hinterland. The main aim was to oppose the French advancing from the north-west and north and the Germans advancing inland from the east . The capital of the Protectorate of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast and also the headquarters of the colonial administration was Tamale .

History of origin

The global economic crisis , which has been going on since the early 1880s , peaked around 1890. The export economy in West Africa almost came to a complete standstill because the importing companies in Europe increasingly disappeared and there was a lack of capital for start-ups. In many parts of Europe, economic expansion in the colonies was seen as a certain opportunity to overcome crises, especially in resource-rich Africa. To do this, however, it was necessary to create a legal framework beforehand that not only allowed the industrial exploitation of raw material sources, but could also secure it with sovereign power. Again and again, lobbyist groups in the European parliaments had urged “to do something”, e.g. B. to guarantee the exploitation of certain sources of raw materials overseas for European industries. So it is not surprising that France and Great Britain concluded an agreement in August 1890 to delimit their spheres of interest in West Africa. Under this treaty, the entire Niger Basin was declared a British area of interest in West Africa, while the Upper Niger and the Niger Arc were given to the French. There was no mention in this treaty of the hinterland of the Gold Coast or other areas of West Africa. This was due to some powerful states that had existed in these areas for a long time, be it the Mossi Emperor with his empire, the Ashanti Empire , the Kingdom of Dahomey or the pirate states that only recently emerged under the guise of Islam, such as Bissandougou of a Samori Touré or the Zabarima emirate of Gazari or Babatu, to name just the most important.

The French competition

Samori

With the support of local chiefs, the French succeeded in 1892/1893 in driving Samori Touré out of the areas of upper Niger and pushing him south to the upper reaches of the Black Volta . Here Samori founded a new Islamic state with Dabakala as its capital, after the appearance of its murderous and plundering sofa gangs had previously led to a certain degree of depopulation in large parts of its new "national territory". Much of the population had either been killed or sold into slavery . The slave trade formed the (pretty much only) economic foundation of Samori's state.

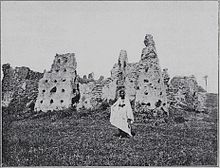

At the beginning of 1895, Samori Touré and his army invaded the Kingdom of Kong, south of his new territory . From the once flourishing trading city Kong (the capital of the empire of the same name), which had previously had a population of 20,000, only smoking ruins remained after the slaughter of Samori's sofa gangs. The same happened to numerous other places in this region. In the hinterland of Ashanti there were also first skirmishes between Samori's sofa troops and British military units in the first half of 1896 , which were particularly concentrated in the area around Wa and in the area of Banda. Numerous villages were conquered from one side and recaptured from the other a short time later. Added to this were the constant skirmishes between the sofas and the French in the north, which forced Samori more and more south. But this was not the only area of tension. The political situation in the Northern Territories was further complicated by the competition between the British and the French over the Gurunsi issue. On the one hand everyone wanted to plant their own flag here, on the other hand they wanted to prevent a possible invasion of the Germans who were advancing from the east. In June 1896, while fighting Samori, Wa was occupied by French troops. This set off all alarm bells among the British and efforts were made quickly to reach an agreement with Samori, but this failed. From the British point of view, an open two-front war threatened, which they tried to circumvent by forcing Samori to take direct action, which, however, indirectly tried to fight the French without having to declare war on France. London then authorized the governor in June 1896 to take Bondoukou by force if necessary . The official pretext was to put an end to the activities of the Samori by all means.

The British governorate then sent military units into the Black Volta regions to fight Samori's murderous gangs, but Samori's troops repeatedly managed to avoid skirmishes with the British. On March 29, 1897, there was a major battle between British units under the command of Francis B. Henderson and Samori's troops. More battles followed, such as B. on April 7, 1897 near Wa, where George E. Ferguson, a senior British officer, was killed.

The Bondoukou case

In June 1897 the British "Inspector General" in Kumasi , O. Mitchell, received the order to expel all sofas from the Banda region and to investigate their position in Bondoukou. A short time later Mitchell received envoys from Chief Pape, who was intriguing against Samori and who, after the death of Gyamanhene Agyemang in early 1897 , had taken over the affairs of state of the Kingdom of Gyaman until a new king was elected. Pape informed Mitchell that a large number of Samori's people had set out for Bouna as early as May 1897 and that he and his supporters were ready to cooperate with the British to drive the enemy out of Bondoukou entirely. Although it was known that Gyaman was officially a French reserve, both sides agreed that a British military detachment should occupy the city on July 7, 1897 amid a general revolt instigated by Pape's people. However, without having received permission from Governor Maxwell, Mitchell left his base in the Banda area on July 5, 1897 and went with a military department via Tambi to Bondoukou.

In Bondoukou, on July 6, 1897, they were in the middle of the installation ceremony for the new Imam Kunadi Timitay when the news arrived that some whites were on the way to Tambi with cannons. Chief Pape then denied to Bakari, Samori's "Chief Lieutenant" in Bondoukou, at his request that he had any knowledge of the British advance. Bakari then left the city with most of his sofas on the morning of July 7, 1897 , while his chief adjudant, Sanusi Dyabi, tried to round up the residents of Bondoukou and move them to a "mass emigration" north. Those he rounded up, however, dispersed again at the first opportunity. Angry at the lack of cooperation, Sanusi ordered Bondoukou to be burned down when night fell. At that point in time, Mitchell's cannons began to fire. At dusk, the British chased the fleeing sofas as far as Barabo, but Mitchell did not consider it advisable to advance further. After a conversation with Chief Pape, he was finally proclaimed the new King of Bondoukou and on July 9, 1897, Mitchell and his men retired to Banda, leaving four soldiers behind at Bokari to watch the sofa movements. The French governor in Grand-Bassam raged with indignation, Governor Maxwell was more than embarrassed by Mitchell's unauthorized action - but the Gyamans cheered.

In order to prevent further actions by British troops on the territory actually under French protection, French troops were immediately marched to occupy Gyaman. In the same year, 1897, the western part of Gyamans was under French control, while the British in turn occupied the eastern part on the orders of Governor Maxwell from Banda. British units reached Bondoukou on September 2, 1897. Governor Maxwell then went to Bondoukou himself, where he arrived on September 27, 1897. Numerous conversations took place and after waiting for the answer to a message sent to Samori, Maxwell set out on the return journey on October 23, 1897. Four days later, a British military detachment of about 300 men under the command of Captain Jenkinson started a campaign against Samori, which was even accompanied by Imam Kunadi Timitay, Chief Pape and numerous Gyaman nobles with their followers. One wanted at all costs to prevent a return of Samori's sofa gangs.

In view of British activities, the French decided to take full possession of Gyaman. Capitaine François Joseph Clozel therefore received the order in Assikasso on November 19, 1897 to go to Bondoukou without delay and to occupy the city. He reached the city on December 5, 1897 and found it in a desolate state. Numerous houses were destroyed. On December 17, 1897, Imam Kunadi finally returned from his Samorian campaign with around 200 armed followers. Chief Pape would follow later. Kunadi made a new agreement with Clozel and also brokered the submission of Chief Pape to French rule.

The end of Samori

Meanwhile wedged in by the French and the British, Samori tried to break out with his sofa gangs to the northwest and was finally captured by the French on September 29, 1898 near Guélémou (Ivory Coast). He was then exiled to Gabon , where he died in 1900. His previous state was declared dissolved after his capture and its territory was incorporated into that of the French West Africa colony .

The Marka jihad and the battle for Boussé

In 1892, under their leader Al-Kari, the Islamic Marka founded their own Islamic state in the north-west and center of what is now Burkina Faso , with Boussé as the capital, which was to become the starting point of a jihad "to further spread the true faith", as it was said. Since the beginning of their jihad, the Marka warriors of Al-Kari had been able to celebrate great successes and conquered large parts of the Samo country (in the northwest of today's Burkina Faso). Here, however, one came across French military units who had previously fought with Samori's gangs and who now also fought the Marka troops with all determination. From a military point of view, the French achieved a small masterpiece. On the morning of July 1, 1894, French troops appeared completely unexpectedly in front of the town of Boussé, while the actual Marka army was south of Koumbara. In Boussé there was a battle with the defenders, which lasted all day. Al-Kari was killed in these fighting and it was said that not a single Marka was found alive afterwards, either on the battlefield or in the ruins of the city. The Marka army completely disbanded after the news of the conquest of their capital, a large part of them turned south to join the Zabarima army of Babatu, who are in the Gurunsi area (in the north of present-day Ghana) then had domicile. He was not necessarily considered a friend of Samori, even if there had been contacts between the two.

The breakup of the Ashanti Empire

The states and territories of the Brong Confederation , which had previously formed the north and north-east provinces of the Ashanti State, had fallen away from Asante in the 1870s and thereafter and had declared their independence from Asante. From them, however, the King of Atebubu had concluded a protection treaty with the British on November 25, 1890.

Adansi, which had formed the southern province of the Ashanti state since the 17th century, had also signed a protection and friendship treaty with the British on October 18, 1895.

Under the pretext of combating Samoris troops British troops on January 17, 1896 occupied on the orders of Governor Maxwell aschantische the capital Kumasi after a the Asantehene posed ultimatum had expired and with which the British approval of establishment of a British resident delegate demanded in Kumasi had. In the eyes of the British, the Ashanti were already regarded as allies of Samori, who supplied them with European weapons. With the occupation of the city, the king (Asantehene) and his most important chiefs were also captured by the British. On August 16, 1896, the British government officially declared that the kingship in Asante had been abolished and the kingdom dissolved and that the previous territory administered from Kumasi was now a protected area of Great Britain. The Asantehene and his entourage were deported to the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean.

In view of the events, the chiefs of Asunafo-Ahafo signed a protection treaty with the British in 1896. Their territory was now a separate British protectorate with the Kukumohene as the highest political authority. With that the southwest of the previous Ashanti empire had also fallen away.

However, there were also some areas where people continued to be loyal to the Ashanti. One such was the region around Assikasso (in the east of today's Ivory Coast), which had been a province of Asantes since the 18th century. With the British victory over Asante in 1874, Assikasso was granted independence. In view of the British march in Asante and the further advance of the British to the north, the French also tried to show a military presence as quickly as possible and as close as possible to the British protected areas. So was u. a. A French military post was also set up in Assikasso, which, however, provoked resistance from the locals. In 1898, therefore, the military post in Assikasso was besieged by local warriors and a message was sent to the French governor stating that they were related to the Ashantis and other Akan tribes and that the French had no right to Akan territory to occupy. However, the French saw Assikasso as part of the Kingdom of Gyaman , with which a protection treaty had been concluded in 1888. Assikasso was then occupied by French military units in 1898 and officially declared part of the French colony of Ivory Coast.

The establishment of the protectorate

With the crackdown on Samori and the suppression of the Marka jihad, the French had occupied large parts of northern Ivory Coast and Mossi country. In order to prevent the French and Germans from using the fight against privateer kings like Samori or Babatu as an opportunity to occupy and claim lands north of the former Ashanti Empire, the British Protectorate of the Northern Territories was established in 1897.

The Zabarima

The Zabarima had once come to Dagomba as horse traders in the early 1860s or shortly before. However, since the Dagomba had taken some time to pay for their goods, the majority of the Zabarima traders in Dagomba land had settled at home. In order to have a livelihood, they initially took part as mercenaries in the slave hunts of Adama, the then chief of Karaga in Dagomba. At that time, Dagomba had to pay tribute to the Ashanti Empire and paid its annual tribute mainly in the form of slaves. In the late 1880s, however, the rift between the Zabarima and the Dagomba occurred and the former moved further west, where the slave hunts were continued in Gurunsi land on their own account and finally their own emirate was founded here. The first emir of Zabarima country was Gazari , after his death, under his successor as emir, Babatu dan Isa , the slave hunts in the areas of what is now northern Ghana and southern Burkina Faso continued. Although they have professed the Islamic faith themselves, even malams have been captured and sold as slaves in the areas they have struck .

Together with local allies, the French finally succeeded in defeating Babutu and his Zabarima army on March 14, 1897 in the Battle of Gadiogo (Burkina Faso). The rest of his troops were again defeated by the French on June 23, 1897 near Doucie (Burkina Faso). However, some of the Zabarima troops managed to flee south, where from October 1897 they fought constantly with British military units until the last remnant of Babutu's private army was defeated in June 1898.

Demarcation

Representatives of the French and British governments had previously reached another temporary agreement at Yaruba on April 20, 1897, on the delimitation of their areas of interest in the regions of the Upper Volta, which was again amended with a border treaty of June 14, 1898. Roughly speaking, this line also forms today's border between Ghana and Burkina Faso.

With regard to the eastern border of the Protectorate, the representatives of Great Britain and the German Empire signed an agreement on November 14, 1898 on the delimitation of their respective spheres of interest between the gold coast hinterland and the Togo area. The previous neutral zone in the Salaga area was declared dissolved and a border was drawn, which ran roughly in north-south direction from the mouth of the Dako River into the Volta over long stretches along the Dako River. The Mamprussi and the Tschokossi, through whose territory the border ran, were given the option to move to their tribal comrades on the other side of the border if they wanted to. With regard to the Dagomba, however, the organization of such an undertaking was impossible due to the territorial size of their settlement area. They continued to be divided.

With regard to the western border, the question of Gyaman and the related territorial claims of the two conial powers France and Great Britain prevented a quick agreement. Only after tough diplomatic negotiations was it agreed on a joint border commission, which was to travel the area in 1902/1903 and set the Franco-British border between the sea coast and 11th parallel north, which was what happened. The borderline agreed at that time still essentially forms the western border of Ghana to the Ivory Coast or in the northern section to today's Burkina Faso.

In 1956, following a referendum in the British mandate of Togoland, which had existed since the First World War, the eastern border of the Protectorate expanded further east. This border line still forms the upper section of the border between the republics of Ghana and Togo today.

Footnotes

- ↑ The establishment of the Protectorate was primarily a response to the French West Africa colony established by the French on June 16, 1895 , which included, among other things, areas of the present-day republics of Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso as French sovereignty, to which it was still at the time there was no demarcation. In addition, in many areas, French sovereignty was only on paper anyway, because at that time there was no question of a French military presence or even a civil administration in most areas. For example, when the kingdom of Gyaman , one of the former provinces of Asante, was threatened by Samori's troops, there was not a single French soldier in the entire kingdom with whom one could confront Samori. From today's perspective, it seems that the British, for their part, saw this as their chance to expand their dominance over economically lucrative areas further inland, provided that these were not yet claimed by other European nations and could also be defended as such. The Kingdom of Gyaman was a special case in this context, as the trip of the governor of the British gold coast colony to Bondoukou (capital of Gyaman) in September 1897, because Bondoukou was already part of the French protected area at that time.

- ↑ A member of Samori's army was called a sofa . Although they appeared under the guise of an Islamic “ jihad ”, their main interests were robbery, murder and looting and they made no difference whether their victims were of Islamic faith or not. Most of the mosques found in their incursion areas were also destroyed, at least this was the case in the northeast of Ivory Coast and in the northwest of present-day Ghana.

- ^ In the north of today's Republic of Ivory Coast.

- ↑ Bondoukou is the capital of Gyaman and a traditional trading hub that has been established as a stopover in trade between the sea coast and the trans-Saharan caravan routes in the north since the appearance of the Europeans in this part of Africa. In addition, there were rich gold fields near Bondoukou near Assikasso, which were considered centers of gold production well before colonial times. In those days Bondoukou was part of the French reserve.

- ↑ The Marka (sometimes also referred to as Malaga) are a Mandé- speaking people in the north-west of today's Burkina Faso, who only immigrated to this region from today's Mali in the course of the 18th and 19th centuries. They first settled in small separate colonies in the middle of the Samo and Bwa, mainly in the north and center of the Dafina region.

- ↑ His real name was Achmadu Demé.

- ↑ A very strange step from today's point of view, because shortly before the British government had rejected an application by the Kwahu nation to join the gold coast colony. To get to Atebubu by the shortest route from Accra, if you ignore the Volta River, you have to travel through Kwahu and part of eastern Asante. In addition, Atebubu belonged to the core area of the Brong Confederation at that time.

- ↑ Asunafo Ahafo has been the southwestern outer province of Asante with Mim as the most populous city. The province borders in the north on Brong-Ahafo, partly with the river Tano as a border and in the south on Sefwi , where the former southwest border of Asante ran. In the west the river Bia forms the border and in the east the roughly straight line between the city of Babianehe (belongs to Sefwi) and the city of Nsuta (belongs to Asante) forms the border.

- ↑ Apparently the Ahafo chiefs had asked for British protection after they had refused to honor the tribute demands that the Kumasi chiefs continued to make on them despite the deposition of the Asantehene and the dissolution of the Ashanti Empire. For the Kumasi chiefs, Ahafo was part of the "islands" of the Kumasi state, that is, one of the border marks on the outer borders of the empire, over which some of the Kumasi chiefs raised property claims separately from one another and demanded tribute for themselves. The rejection of these claims was an important more common point of agreement among all Ahafo chiefs. Especially those who had previously been loyal to the Ashanti king did not necessarily see their subordination to the Kumasi chiefs with enthusiasm. Recognition of British supremacy was probably seen as the lesser of two evils, but a good means of evading the reach of the Kumasi chiefs.

- ↑ also: Zarma, Dyerma, Dyabarma, Zabarima, Zaberma, Zamberba, Djemabe etc., the Haussa name is Zabarma. They actually come from Niger areas and formed one of the main ethnic groups in the former Songhai Empire. Today's Jerma live mainly in the Republic of Niger in and around Niamey as well as in areas of the former Sokoto Caliphate in the northwest of today's Nigeria. With regard to the privateer army operating in what is now Ghana at the end of the 19th century, however, the name Zabarima has solidified.

- ↑ A "Mallam" (other variants: "Mulla (h)", "Mu'allim") is an Islamic religious title that identifies the graduate of an Islamic school (today a Koran school or Islamic university). In the past, the term was often used as an alternative title for Islamic rulers.

swell

- Timothy L. Gall, Susan Bevan Gall: Worldmark chronology of the Nations , Detroit, San Francisco, London, Boston, 1999

- Pierre Bertaux: Africa - From Prehistory to the States of the Present , Volume 32 of Fischer Weltgeschichte , Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt / Main, 1966

- David Owusu-Ansah, Daniel Miles McFarland: Historical Dictionary of Ghana , London 1995

- Robert J. Mundt: Historical Dictionary of Côte d'Ivoire , London 1995

- AF Robertson: Histories and political opposition in Ahafo, Ghana , In: Africa , 43 (1), 1973, pp. 41–58

- Akbar Muhammad: The Samorian occupation of Bondoukou: an indigenous view , In: The International Journal of African Historical Studies (Boston), 19 (2), 1977, pp. 242-258

- Myron J. Echenberg: Late nineteenth-century military technology in Upper Volta , In: Journal of African History , 12 (2), 1971, pp. 241-254

- Stanislaw Pilaszewicz: The Zabarma conquest on the Gold Coast and Upper Volta. Studies on Haussa Manuscript No. 98017 , In: Africana Bulletin (Warsaw), 37, 1991, pp. 7-18

- AEG Watherstone: The Northern Territories of the Gold Coast , In: Journal of the African Society , 7 (28), 1908, pp. 344-372