Paper boats

| Paper boats | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A large paper boat ( Argonauta argo ) with a housing so badly damaged that part of the clutch oozes out |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the family | ||||||||||||

| Argonautidae | ||||||||||||

| Cantraine , 1841 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||||

| Argonauta | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 | ||||||||||||

| species | ||||||||||||

|

Paper boats or Argonauts ( Argonauta ) are a genus of cephalopods (Cephalopoda) in the kraken (Octopoda) family. They are the only recent genus in the Argonautidae family .

Basic construction and housing

Paper boats vs. Pearl boats

![Left: Biologically correct color image of Argonauta argo from 1896 with the skins of the first pair of arms pulled over the housing. Right: Fantasy representation of a paper boat on the surface of the sea from 1868: Based on descriptions from antiquity (see below), the idea still existed in the 19th century that these skins were used as sails for movement. [1] There are indeed marine animals that practice this type of locomotion (see → Portuguese galley), but paper boats are not one of them. These are almost always below the surface of the sea and, like most cephalopods, use a recoil drive there for movement.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/Argonauta_argo_Merculiano.jpg/255px-Argonauta_argo_Merculiano.jpg)

|

![Left: Biologically correct color image of Argonauta argo from 1896 with the skins of the first pair of arms pulled over the housing. Right: Fantasy representation of a paper boat on the surface of the sea from 1868: Based on descriptions from antiquity (see below), the idea still existed in the 19th century that these skins were used as sails for movement. [1] There are indeed marine animals that practice this type of locomotion (see → Portuguese galley), but paper boats are not one of them. These are almost always below the surface of the sea and, like most cephalopods, use a recoil drive there for movement.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/98/FMIB_50479_Argonaut_sitting_in_the_open_sea.jpeg/130px-FMIB_50479_Argonaut_sitting_in_the_open_sea.jpeg)

|

|

|

Left: Biologically correct color image of Argonauta argo from 1896 with the skins of the first pair of arms pulled over the housing.

Right: Fantasy representation of a paper boat on the surface of the sea from 1868: Based on descriptions from antiquity (see below ), the idea still existed in the 19th century that these hides were used as sails for movement. There are indeed marine animals that practice this type of locomotion (see → Portuguese galley ), but paper boats are not one of them. These are almost always below the surface of the sea and, like most cephalopods, use a recoil drive there for movement. |

||

The pearl boats ( Nautilus ) are the only recent cephalopods with a solid, chalky exoskeleton in the form of a high, spirally wound and chambered housing. Paper boats apparently also have such a housing, which in the case of the large paper boat ( Argonauta argo ), the largest species of the genus, can be more than 30 cm long.

However, unlike the pearl boats, paper boats belong to the octopuses (Octopoda), which can be recognized by the fact that they only have eight, but strong arms, which are each reinforced with two rows of suction cups (see also external systematics ). In the octopus, all mineral hard parts (of the housing) have been completely regressed in the course of evolution . The spiral, but not chambered casing of the paper boats is not a "real" exoskeleton, homologous to the casing of the pearl boats , but a secondary formation. It differs from the housing of the pearl boats in numerous details, including the fact that it is not permanently connected to the soft body via muscles and ligaments. Instead, it is held on the inside with the suction cups of the arm ring that is put over the head and coat. In English, this housing is therefore also called pseudo-conch (' pseudo-housing '). The calcium for the casing is deposited (secreted) by the glands of the flat, thin membranes on the distal section of the two arms of the 1st (uppermost, dorsal) pair of arms. These skins equipped with chromatophores can be placed over the entire outer surface of the housing.

In the pearl boats, on the other hand , the casing is secreted by the coat , that is, by the fleshy shell of the intestinal sac, which is permanently almost completely in the living chamber of the shell, while the around 90 suction-cupless arms (cirrus) are completely free. In addition, the shell of the pearl boats consists mainly of the lime modification aragonite , while that of the paper boats mainly consists of the lime modification calcite and is also significantly thinner and more fragile. The German trivial names 'Perlboot' for Nautilus (after the aragonite shell substance mother-of-pearl ) and 'Papierboot' for Argonauta are derived from the different properties of the housing .

Function of the housing

The housings of the paper boats, which are only trained by the females, serve as containers for their clutch (see below ). In addition, it has long been assumed that air trapped in the upper (dorsal) part of the housing plays a role for buoyancy and the body position in the water column in these epipelagic animals - in analogy to the housings of pearl boats. This hypothesis was finally confirmed by observations on animals caught in a harbor basin: females, in whom all air had been removed from the housing before being released into the harbor basin and who therefore had negative buoyancy, immediately swam to the surface of the sea and scooped as much air as possible . The animals then actively swam with the help of the recoil apparatus to a depth at which the buoyancy of the air, which was increasingly compressed by the increasing pressure, was just large enough to keep the animal in suspension. The shell opening was sealed with the arms of the 2nd pair of arms so that the trapped air could not escape. Any remaining air outside the sealed part of the shell escaped during the downward swim. After reaching the "depth of equilibrium", the test animals then only moved horizontally.

Reproduction

Paper boats are not only sexually separated , as is common with cephalopods , but also show extreme sexual dimorphism with a female that is many times larger (see also → dwarf male ). As with most octopuses, fertilization takes place through a specially modified arm of the male, the Hectocotylus . In contrast to other octopuses, the hectocotylus with the spermatophore detaches completely during copulation and becomes an autonomous fertilization unit. The male likely dies shortly after losing the hectocotylus. The female has a much longer lifespan and can be mated by numerous males during this period.

In fact, the severed arm of the male of the paper boats is scientifically known much longer than the rest of his body, and the name, hectocotylus' is originally the generic name of the parasitic, living in the mantle cavity of the female nematode , for which one it held in the early 19th century .

Food and predators

Female paper boats feed on planktonic snails ( heteropods , pteropods ), small fish and possibly also planktonic small crustaceans ( hyperiids , copepods ). It has also been observed that they not only eat (on) jellyfish , but also use them for food. After ' capping ' the jellyfish, they hold it to the top of the umbrella (exumbrella) with the suction cups of the side (lateral) and lower (ventral) arms and first eat parts of the gelatinous tissue of the umbrella. Eventually they bite through to the gastrovascular space ('stomach'). Then they can use the highly effective mouth arms of the jellyfish to catch planktonic prey for themselves. It is also assumed that paper boats used to socialize with jellyfish also serve as camouflage and, because of their poisonous tentacles, as protection against predators.

With regard to its energy requirements, it has been calculated that a five-gram paper boat under the conditions of the tropical East Pacific has to eat about two small (0.1 gram each) fish or 50 hyperiids (0.01 gram each) per day in order to achieve its normal metabolic rate to be able to maintain.

Paper boats are eaten by larger bony fish (e.g. by the sailfish ), by marine mammals (e.g. by the killer whale ) and by larger sea birds (e.g. by the silver petrel ).

Distribution, frequency and group behavior

Unlike many other octopuses, paper boats have an epipelagic way of life. They are found in the tropical and subtropical, as well as in the southern temperate regions of all seas. Occasional observations of large concentrations of these animals, for example off Japan , as well as the fact that female Argonauta nodosus sometimes wash up on the Australian coast by the thousands, show that large populations must exist. Nevertheless, paper boats are rarely found on the high seas.

The highest geographical latitude reported by paper boats in the north-east Atlantic is 42 ° North, although these are animals that are transported northwards from lower latitudes by strong south-westerly winds with corresponding drift currents . Since the northernmost encounters both with paper boats and with representatives of other tropical and subtropical taxa in the North Atlantic took place a little further south in the past, the advance of a paper boat up to a latitude of 42 ° is associated with global warming .

In the case of Pacific paper boats (especially A. nouryi ) it has been observed that several females form "chains" by attaching themselves to one another. The cause of this behavior is unclear. It is assumed that in this way the females save energy for locomotion, among other things, and are easier to find for males in the open ocean, although such aggregates can also be more easily detected by predators.

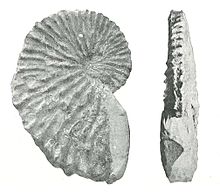

Fossil record

Argonautid remains are relatively rare in the fossil record . Most of the finds come from the edge zone of the western Pacific and especially from Japan. The geologically oldest representative is † Obinautilus pulcher from the Oligocene (33.9 to 23.03 mya ) of Japan. The genus Argonauta appears for the first time in the Middle Miocene (15.97 to 11.62 mya ) of Japan († A. tokunagai ), Cyprus († A. absyrtus ) and Austria († A. johanneus ) in the fossil record. The latter two are also the oldest of the few records from the western Tethys and from the Paratethys . From the edge zones of the Atlantic (excluding the Mediterranean Sea) no fossil argonautid finds are known.

Systematics

External system

The genus Argonauta is the only recent and the type genus of the family Argonautidae and the type genus of the superfamily Argonautoidea . The Argonautoideen are one, but not the only group of pelagic forms within the octopuses (Octopoda), which are predominantly characterized by benthic representatives. As the closest relatives of the "octopuses in the narrower sense" (Octopodoidea or Octopodidae ), they are combined with them in the Incirrata group become. In the simplified cladogram below, a probable position of the Argonautids within the recent cephalopods is shown graphically (after Lindgren et al., 2012).

| Cephalopods (cephalopoda) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Internal system

Within the genus Argonauta, at least four recent species are currently (as of 2013) differentiated from one another based on the soft body anatomy of both sexes and the morphology of the housing:

- A. argo Linnaeus , 1758 - the largest, most widespread and type species

- A. hians Lightfoot , 1786 - Main distribution area: tropical and subtropical western Pacific and Ind

- A. nodosus Lightfoot , 1786 - restricted to subtropical and temperate southern latitudes

- A. nouryi Lorois , 1852 - restricted to the tropics and subtropics of the Eastern Pacific

Some authors have also recognized the species A. gruneri Dunker , 1852, A. cornutus Conrad , 1854 and A. boettgeri Maltzan , 1881, which, however, may be identical to A. nouryi (the former) or A. hians ( the latter two) are. In addition, several dozen other species have historically been described, especially in the 19th century, often solely on the basis of shells washed up on beaches. The intraspecific variation of the paper boat housings is relatively high, so that the names coined here had to be synonymous with those of the above-mentioned species .

Etymology and reception in ancient times

The paper boats, which are also at home in the Mediterranean, were received in the art and culture of the ancient Mediterranean peoples to an unusually high degree for an invertebrate animal. They were a popular decorative motif in Minoan art , especially for ceramic vessels of the marine style . Similar representations as in the old Cretan sea style can also be found on the bronze blades of approximately the same old Mycenaean decorative daggers.

In his zoological studies , the famous ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle describes the paper boats as' nautilos' (ναυτ Tierλος) and already correctly recognizes them as octopuses (πολύπους, polypous'). The word 'nautilos' is a poetic form of the word 'nautes' (ναύτης), which means something like 'sailor' or 'seafarer'. The legend goes back to Aristotle that the paper boats use the skins of their dorsal alarms as sails for movement on the surface of the sea. This was rumored by later ancient authors such as Pliny and can still be found in natural history books of the 19th century. Pliny, a Roman , called the paper boats 'Pompylius'. For the Romans, the sighting of a paper boat during a sea voyage was considered an omen that it had gone well.

The ancient descriptions apparently inspired Carl von Linné to use the zoological generic name Argonauta , which is still valid today and which he coined in 1758 in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturæ . It goes back to the Argonauts legend , in which the Greek hero Jason sets out with his comrades-in-arms to conquer the golden fleece . They are named after their sailing ship, the Argo, the Argonauts ('who sail on the Argo'). The names of the paper boat, which were actually used in antiquity , were chosen by Linnaeus for another animal species, the common pearl boat ( Nautilus pompilius ), which has an outwardly similarly shaped housing, but, according to current knowledge, is only a distant relative of the cephalopods Paper boats is (see above ) and, moreover, does not occur in the Mediterranean.

swell

General

- Guido T. Poppe, Yoshihiro Goto: European Seashells. Vol II (Scaphopoda, Bivalvia, Cephalopoda). Verlag Christa Hemmen, Wiesbaden, 1993 ISBN 3-925919-11-2 .

- Julian K. Finn: Family Argonautidae Tryon, 1879. pp. 228-237 in Patrizia Jereb, Clyde FE Roper, Mark D. Norman, Julian K. Finn (eds.): Cephalopods of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalog of cephalopod species known to date. Volume 3. Octopods and Vampire Squids. FAO Species Catalog for Fishery Purposes No. 4, Vol. 3. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome 2014 ( online ; PDF 4.8 MB = only Chapter 2.1. Incirrate Octopods).

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Louis Figuier: The ocean world: being a descriptive history of the sea and its living inhabitants. Chapman & Hall, London 1868, doi: 10.5962 / bhl.title.99574 , p. 460 ff.

- ↑ a b cf. Marion Nixon: Part M: Mollusca 5, Vol. 1. Chapter 5: Reproduction and Lifespan. Treatise online. No. 13, 2010, doi: 10.17161 / to.v0i0.4083 , Fig. 1.

- ^ Julian K. Finn and Mark D. Norman: The argonaut shell: gas-mediated buoyancy control in a pelagic octopus. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences. Vol. 277, 2010, pp. 2967-2971, doi: 10.1098 / rspb.2010.0155 (Open Access); see also the article Kraken draw air from May 19, 2010 on Scienceticker.info (German).

- ↑ cf. in addition the overview of the literature published up to then in Albert Kölliker: Hectocotylus argonautae D. Ch. and Hectocotylus tremoctopodis Köll., the males of Argonauta argo and Tremoctopus violaceus D. Ch. Reports from the Royal Zootomic Institute in Würzburg. Second report, 1849, pp. 67-89 ( BSB OPACplus ); Note: in this work the Hectocotyli of the male of Argonauta and the closely related genus Tremoctopus (see external systematics ) are not interpreted as parasites, but as the complete , extremely degenerate male individuals of these genera that are actually reduced to the sexual apparatus.

- ↑ Thomas Heeger, Uwe Piatkowski, Heino Möller: Predation on jellyfish by the cephalopod Argonauta argo. Marine Ecology Progress Series. Vol. 88, 1992, pp. 293-296, doi: 10.3354 / meps088293 (Open Access).

- ↑ a b c d Rui Rosa, Brad A. Seibel: Voyage of the argonauts in the pelagic realm: physiological and behavioral ecology of the rare paper nautilus, Argonauta nouryi. ICES Journal of Marine Science. Vol. 67, 2010, pp. 1494-1500, doi: 10.1093 / icesjms / fsq026 ; with regard to the feeding habits and predators of paper boats, see the literature cited therein.

- ↑ T. Okutani, T. Kawaguchi: A mass occurrence of Argonauta argo (Cephalopoda: Octopoda) along the coast of Shimane Prefecture, western Japan Sea. Venus - Japanese Journal of Malacology. Vol. 41, No. 4, 1983, pp. 281-290, cited in Katharina M. Mangold, Michael Vecchione, Richard E. Young: Argonautidae Tryon, 1879, Argonauta Linnaeus 1758, paper nautilus. The Tree of Life Web Project, November 16, 2016 version, accessed March 6, 2017.

- ↑ Mark Norman, Amanda Reid: Guide to Squid, Cuttlefish and Octopuses of Australasia. CSIRO Publishing Gould League of Australia, Collingwood (VIC) Moorabbin (VIC), 2000, p. 79 ISBN 0-643-06577-6 .

- ↑ A. Guerra, AF Gonzalez, F. Rocha: Appearance of the common paper nautilus Argonauta argo related to the increase of the sea surface temperature in the north-eastern Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Vol. 82, No. 5, 2002, pp. 855-858, doi: 10.1017 / S0025315402006240 (alternative full text access : Digital.CSIC ).

- ^ A b David Martill, Michael J. Barker: A paper nautilus (Octopoda, Argonauta) from the Miocene Pakhna Formation of Cyprus. Paleontology. Vol. 49, No. 5, 2006, pp. 1035-1041, doi: 10.1111 / j.1475-4983.2006.00578.x (Open Access).

- ↑ Annie R. Lindgren, Molly S. Pankey, Frederick G. Hochberg, Todd H. Oakley: A multi-gene phylogeny of Cephalopoda supports convergent morphological evolution in association with multiple habitat shifts in the marine environment. BMC Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 12, item no. 129, 2012, doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2148-12-129 (Open Access).

- ↑ a b Julian K. Finn: Taxonomy and biology of the argonauts (cephalopods: Argonautidae) with Particular reference to Australian material. Molluscan Research. Vol. 33, No. 3, 2013, pp. 143–222, doi: 10.1080 / 13235818.2013.824854 , list of recognized species and lists of synonyms quoted in Serge Gofas: Argonauta Linnaeus, 1758. MolluscaBase (2016). Accessed via: World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) on March 7, 2017.

- ^ Hermann Aubert, Friedrich Wimmer: Aristoteles Thierkunde - critically corrected text with German translation, factual and linguistic explanation and complete index. First volume. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1868 ( HathiTrust ), p. 149 .

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott: A Greek-English Lexicon. 8th, revised edition. American Book Company, 1901 ( archive.org ), p. 993 .

- ↑ a b c Carolus Linnæus: Systema Naturæ. 1st volume. 10th, revised edition. Stockholm, 1758, doi: 10.5962 / bhl.title.542 , p. 708 f.

Web links

- ArgoSearch - Website about a research project on paper boats under the domain of the Museum Association of the State of Victoria (Museum Victoria) (English)

- Videos on YouTube:

- A paper boat (according to the title of the video Argonauta hians ) swimming in the open water

- Close-up of a paper boat (probably also A. hians ) in the aquarium