Pholidocercus

| Pholidocercus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

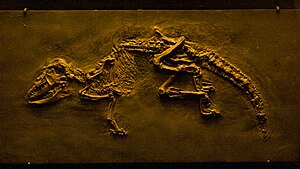

Pholidocercus skeleton |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Eocene | ||||||||||||

| 47.4 to 46.3 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Pholidocercus | ||||||||||||

| by Koenigswald & Storch , 1983 | ||||||||||||

Pholidocercus is a now extinct genus of insectivore-like mammals. It lived in the Middle Eocene around 47 million years ago and is only known from the Messel Pit in Hesse with the help of several, partly complete skeletons. The rather small and long-tailed animals lived on the ground and fed on plants and insects in an omnivorous way. The most striking features were a horn plate on the skull and protective armor on the tail consisting of bone plates. In general, the genus is assigned to the family Amphilemuridae , which according to some researchers ismore closely related totoday's hedgehogs . According to other studies, a closer bond to the elephant family is also an option. The first description of pholidocercus carried 1,983th

description

Pholidocercus was a small, stocky, insectivore-like mammal with a head-trunk length of around 19 cm and a tail length of a good 16 to 18 cm. The rather short legs are a general feature. The skull measured about 5.5 cm, but the known skulls are largely crushed by sediment. However, there is a sharply delimited area on the nasal and frontal bones with deep vascular channels that encourage the formation of a horny plate or skin callus. Three mental foramina were formed on the lower jaw, one each under the second and fourth premolar and one under the first molar . The dentition comprised the full number of teeth of the early higher mammals , accordingly the tooth formula is as follows: The teeth lying in front of the molars were hardly more differentiated and were largely spatula-shaped. In the upper jaw, the first incisor and the canine had a larger design, in the lower jaw the canine and the premolars, which were also somewhat modified here. Only the rearmost premolar showed signs of molarization and was therefore more similar to the rear molars, and it was also significantly larger than the preceding teeth. The molars had several, clearly rounded enamel cusps ( bunodont ), which were arranged in a typical tribosphenic chewing surface pattern. This means that three bumps formed a characteristic group of three ( trigon ), which was separated from the others by a deep groove ( talon ). The largest teeth represented the first two molars, which reached a length of 3.6 to 3.9 and a width of 4 to 4.4 mm.

The body skeleton is largely well documented. The spine was most likely composed of 7 cervical, 11 rib-bearing thoracic, 8 lumbar, 2 sacrum and 24 caudal vertebrae. The spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae were long, narrow and directed backwards, up to the tenth vertebra, where it stood upright. The lumbar vertebrae, on the other hand, had wide and short spinous processes. In general, the caudal vertebrae were long and narrow. However, a protective armor from the 4th to the 16th vertebra appeared as a unique formation , which consisted of annularly arranged bone plates. The bone platelets were formed from ossification of the skin ( osteoderms ) and had an approximately rectangular shape. The individual rings overlapped like roof tiles from front to back and were turned towards each other in such a way that the arrangement of the individual bone plates appeared like a wall. In the anterior tail section, each ring consisted of 15 to 18 platelets, in the middle of 10, in the rear this could not be precisely determined.

Only a few peculiarities can be identified in the musculoskeletal system. The humerus was elongated and up to 3.3 cm long. The ulna and radius were not fused, but completely separated. The upper elbow joint ( olecranon ) did not have any particular extension; a groove ran along the shaft of the up to 2.6 cm long ulna as a muscle attachment point. The thigh bone reached up to 3.8 cm in length and was also straight. A clearly extended third trochanter appeared on the shaft as a muscle attachment point, which took up about two thirds of the shaft length. The lower leg bones - tibia and fibula - were fused together in the lower area. The length of the tibia was equal to or slightly greater than that of the thigh bone. Arms and legs each ended in five rays. The central ray (III) was strongest on both the hands and the feet, and the outermost (I and V) the shortest. In contrast to the closely related Macrocranion, there were no noticeable extensions of the metatarsal bones and phalanges on the feet . The end links of the phalanges on the hand and foot had clear fissures at the front, which suggest strongly anchored, long claws. From the shape of the terminal phalanges it can be concluded that they were neither particularly wide nor narrow. The entire foot measured up to 4.4 cm.

Fossil finds

Pholidocercus has so far only been handed down from Central Europe , finds here come from the Messel mine near Darmstadt in Hesse. The site is dated to the Middle Eocene and is around 47 million years old. The material known to date comprises at least ten individuals, including three largely complete skeletons, a partial skeleton without a skull and an isolated skull. As is customary for most of Messel's higher mammals, the skeletons were lying on their side, with three being on the right and one on the left. Especially in the skull-less skeleton, the horn scaling of the tail has been passed down extremely well. Of the five known individuals, only one is fully grown, three are sub- or young adults, and the finding without a skull cannot be assigned to an exact age group.

Paleobiology

The less specialized anterior dentition and the distinctive bunodontic molars suggest a general omnivorous lifestyle, similar to the closely related Macrocranion . Since the tooth morphology of the posterior molars in Pholidocercus is even simpler due to the clearly rounded enamel cusps, an increased proportion of softer food components can be assumed. Three of the Messel skeletons contained food residues in the gastrointestinal area. In two of the samples examined, a larger proportion of plant residues was found in addition to sand, such as leaf parts and non-determinable material. In addition, chitin fragments from insects were identified. A third individual had abundant insect material in the digestive tract. Remains of fruits have been handed down to plants here . According to this, Pholidocercus actually lived omnivorously , whereby the sand found indicates that the animals mainly looked for their food on the ground.

The body skeleton shows only a few special adjustments. The longer hind legs compared to the shorter front legs are striking. In relation to the length of the trunk spine, the individual sections of the foreleg (upper arm, forearm and hand) each reach between 18 and 28%, the corresponding sections of the hind leg (thigh, lower leg and foot) each between 35 and 39%. In relation to that, it is similar to that of the actual shrews ( Tupaia ), which means that a certain jumping ability can be assumed when moving. This is supported by the extensive third trochanter on the thigh bone. However, since the lower leg sections of the hind limbs are not excessively elongated, as is the case with Macrocranion , a two-legged hopping locomotion can be excluded. In contrast to today's actual pointed squirrels, most of which live tree-dwelling, in Pholidocercus the terminal phalanges are not narrowed and high, which is typical for claw-climbers. The outer rays of the hands and feet also show significant cuts that limit the ability to grip. Frequent climbing in the trees can also be excluded. A widening of the hands or an extension of the central steel with a strong claw as well as an extensive joint at the upper end of the ulna were missing, generally indications of a digging activity as with the armadillos and pangolins , which means that such a way of life is not to be assumed. It is possible, however, that the split end phalanges allowed a certain amount of scratching in the ground, the splits serving to firmly anchor the claws. Thus Pholidocercus lived largely ground-dwelling, which occasionally rummaged underground for food. Possibly the latter occurred with the forehead and nose, as indicated by the calloused forehead plate.

Using a skeleton, it was also possible to reconstruct the fur cover that had been retained in the surrounding sediment as a trace by bacteria ( bacteriography ). Thereby, a coat is detected consisting of long and sharp bristles to which the similarities hair hedgehog (Hylomyinae) reveals. The longer hind legs prevented Pholidocercus from curling up, as is the case with today's hedgehogs (Erinaceinae), which have about the same length of front and rear legs. Furthermore, the bristles of Pholidocercus could not be erected in the same way as the hedgehogs in case of danger. This is supported by the long, backward-facing and unspecialized spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae. Today's hedgehogs, on the other hand, have highly specialized, short, upward-oriented spinous processes, which are associated with a slight lateral rotation of the front body. They are a result of the formation of extremely strong longitudinal muscles in the back, which allow the sting of the hedgehog to straighten up. In the case of Pholidocercus, however, the tail with its overlapping horn scales can be seen as an effective protective device ; the horn plate on the skull may also have had such an additional function.

Systematics

Pholidocercus is a genus from the now extinct family of Amphilemuridae . The family is characterized, among other things, by the original number of teeth in the teeth for higher mammals. The lower teeth stand in a closed row and incline increasingly forward in the front section. In addition, they are all single-rooted. The Amphilemuridae are often seen as very original representatives of the Erinaceomorpha and are therefore close to today's hedgehogs . Macrocranion and Amphilemur , among others, are closely related . Numerous skeletons of the former have come down to us from Messel, the latter is known with individual lower jaw fragments from the Geiseltal. The Erinaceomorpha (these were originally part of the insectivores ) represent a member of the superiority of the Laurasiatheria represents one of the four major main lines of higher mammals. As early as the late 1980s, however, the assumption was made that due to tooth and skull features a reference to the insectivores was not guaranteed. Further investigations see the Amphilemuridae and the closely related Adapisoricidae in the ancestral line of the African elephants (Macroscelidea), which is mainly based on the tooth morphology. For this reason, the Amphilemuridae including Pholidocercus would have to be assigned to the parent group Afrotheria . After further investigations, the Amphilemuridae could remain in the closer hedgehog relationship.

The first scientific description of Pholidocercus was made by Wighart von Koenigswald and Gerhard Storch in 1983. The basis for this was formed by the five known individuals from the Messel Pit , whereby the holotype (specimen number HLMD 7577) comprises the complete skeleton of a fully grown animal, but its rear tail absent, while some teeth on the right half of the skull and individual osteoderms are isolated. The object is now in the Hessian State Museum in Darmstadt . The generic name Pholidocercus is derived from the Greek words φόλις , φολίδος ( pholis , pholidos "scale") and χέρχος ( cercos "tail") and refers to the conspicuous tail armor. The only recognized species is Pholidocercus hassiacus , with the additional species referring to the Hesse find landscape. In their first description, the authors referred the genus to the family Amphilemuridae. The closely related Macrocranion , passed on from Messel among others, was included in different families in the course of research history, and it was not until 1995 that it was clearly assigned to the Amphilemuridae.

literature

- Thomas Lehmann: With or without spikes - the hedgehog relatives. In: Stephan FK Schaal, Krister T. Smith and Jörg Habersetzer (eds.): Messel - a fossil tropical ecosystem. Senckenberg-Buch 79, Stuttgart, 2018, pp. 235–239

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Wighart von Koenigswald and Gerhard Storch: Pholidocercus hassiacus, an amphilemurid from the Eocene of the "Messel Pit" near Darmstadt (Mammalia, Lipotyphla). Senckenbergiana lethaea 6, 1983, pp. 447-495

- ↑ a b c Thomas Lehmann: With or without spikes - the hedgehog relatives. In: Stephan FK Schaal, Krister T. Smith and Jörg Habersetzer (eds.): Messel - a fossil tropical ecosystem. Senckenberg-Buch 79, Stuttgart, 2018, pp. 235–239

- ↑ Gotthard Richter: Studies on the nutrition of Eocene mammals from the Messel fossil site near Darmstadt. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 91, 1987, pp. 1-33

- ↑ a b Gerhard Storch: Paleobiology of Messel erinaceomorphs. Palaeovertebrata 25, 1996, pp. 215-224

- ↑ a b Gerhard Storch and Gotthard Richter: On the paleobiology of the Messel hedgehogs. Natur und Museum 124 (3), 1994, pp. 81-90

- ↑ Wolfgang Maier: Macrocranion tupaiodon Weitzel, 1949, a hedgehog-like insectivore from the Eocene by Messel and its relationship to the origin of the primates. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolution Research 15, 1977, pp. 311-318

- ↑ Wolfgang Maier: Macrocranion tupaiodon, an adapisoricid? Insectivore from the Eocene of 'Grube Messel' (Western Germany). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 53 (1/2), 1979, pp. 38-62

- ^ A b c Gerhard Storch: Morphology and palaobiology of Macrocranion tenerum, an Erinaceomorph from the Middle Eocene from Messel near Darmstadt. Senckenbergiana lethaea 73, 1993, pp. 61-81

- ↑ Florian Heller: Amphilemur eocaenicus ng et n. Sp., A primitive primate from the Middle Eocene of the Geiseltal near Halle a. S. Nova Acta Leopoldina NF 2, 1935, pp. 293-300

- ↑ Kenneth D. Rose: The beginning of the age of mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2006, pp. 1–431 (pp. 144–147)

- ↑ Jerry J. Hooker and Donald E. Russell: Early Palaeogene Louisinidae (Macroscelidea, Mammalia), their relationships and north European diversity. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 164, 2012, pp. 856-936

- ↑ Jerry J. Hooker: New postcranial bones of the extinct mammalian family Nyctitheriidae (Paleogene, UK): Primitive euarchontans with scansorial locomotion. Palaeontologia Electronica 17 (3), 2014, p. 47A (1–82) ( [1] )

- ↑ Carly L. Manz and Jonathan I. Bloch: Systematics and Phylogeny of Paleocene-Eocene Nyctitheriidae (Mammalia, Eulipotyphla?) With Description of a new Species from the Late Paleocene of the Clarks Fork Basin, Wyoming, USA. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 22 (3), 2015, pp. 307-342