Platelet snake

| Platelet snake | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Flat sea snake ( Hydrophis platurus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Hydrophis platurus | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1766) |

The platelet snake ( Hydrophis platurus , syn .: Pelamis platura ) is a snake from the subfamily Hydrophiinae (sea snakes). It occurs worldwide in tropical oceans with the exception of the Atlantic and was long considered the only member of the genus Pelamis . More recent molecular biological studies suggest, however, that it belongs to the genus Hydrophis .

description

The species usually reaches a body length of about 80 centimeters, occasionally body lengths of up to 113 centimeters are given, with the females being slightly larger than the males. It usually remains smaller in the western part of its range, up to about 75 centimeters. The body is flattened laterally along its entire length, with a widened, flat oar tail. Only the relatively small head is flattened when viewed from above (dorsoventral), with a distinctly elongated snout region. The ventral scales ( ventralia ) are small, hardly noticeably enlarged compared to the adjacent rows of scales, their number is 260 to 400 (maximum: 406). They are usually divided by a median longitudinal furrow or even divided into two and then no larger than the adjacent rows of scales. The back scales (dorsalia) are smooth, sometimes the outer rows have two to three small tubercles. They are small, square to hexagonal in shape, about 49 to 67 rows in the middle of the body. The scalps are smooth, regular, and enlarged, with one to two pre-oculars , two to three post-oculars, and six to eight supralabials . The nostrils sit dorsally, the nasals touch on top, without internasals. The fangs are short, only one to two millimeters long, they are separated from the adjacent seven to eleven maxillary teeth by a noticeable distance (diastema).

The species can usually be recognized by its distinctive color and drawing pattern, which, however, is individually very variable. Usually the body is distinctively two-colored from the head to the tail region, with a yellow belly and dark back. On the widened tail, this drawing is broken up into a dark band or patch pattern on a yellow background, almost always with a continuous yellow center line. There are numerous color options; so the belly can be colored brown, it is then usually set off from the dark back with a yellow side line. On the sides of the body, there may be dark spots or bands of different dimensions. The dark back coloration can be narrowed to a narrow band. There are also completely black or yellow colored animals.

The species can be distinguished from related species on the basis of the pattern, the muzzle-shaped elongated head and the distinctive diastema between the poisonous and maxillary teeth.

subspecies

The species is morphologically monotonous in most of its range, probably due to its pelagic way of life. A subspecies Hydrophis platurus xanthos was described in 2017 from the Golfo Dulce on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. This differs from the typical shape in that it has a single, bright canary yellow color, is slightly smaller in size and has some behavioral characteristics. The Golfo Dulce is characterized by partially anoxic oxygen levels. Typically colored individuals (here the only sea snake species) live in the open sea.

distribution

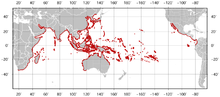

The plateau snake is the most widespread sea snake and the snake species with the largest distribution area. It occurs in tropical and subtropical waters in the Indian and Pacific Oceans from the east coast of Africa, south to South Africa, north to the Gulf of Aden , across South and Southeast Asia, the Australian coasts (with the exception of the south coast), the Pacific island world, including the North coast of the North Island of New Zealand and Hawaii , to the west coast of North and South America. It is common along the American coast from the Gulf of California in the north to the Colombian coast in the south. Since the sea snake also occurs freely swimming away from the direct coast, aborted or drifted individual animals are widely scattered, also away from the permanently colonizable and reproductive area. The propagation of the species is approximately through the 26 degree - isotherm , the stripe area with limited occasionally occurring individual animals by the 18 ° isotherm.

The species, like all sea snake species, is absent in the entire Atlantic Ocean, although there have been quite a number of sightings on the South African coast up to the Cape of Good Hope . Since the family group probably comes from the Pacific, the species cannot reach suitable waters due to a lack of marine connections. Possible reasons that prevent it from spreading along the Namibian coast of South Africa are quite cool water temperatures (due to the Benguela Current ), mostly south-facing winds and a lack of rain (which the species depends on for its water supply). Isolated sightings in the southern Caribbean could be traced back to animals migrating through the Panama Canal , but the establishment of a population seems unlikely here too .

Life cycle

Sexual maturity occurs in males with a body length of approx. 50 cm, in females approx. 60 cm. The species has no particular reproductive period. Females with developing eggs could be seen in tropical waters during all months of the year. A water temperature of over 20 ° C is required for reproduction, so that animals in subtropical latitudes probably only reproduce in summer. 2 to 6 young animals (average value: 4.5) are born each time. Not only feeding and mating, but also the birth of living young takes place in the sea; the sea snake is ovoviviparous . There are anecdotal reports that females like to go to shallower stretches of water when their young are born and that they guard the young for some time. The gestation period is unknown; it is estimated to be around 5 months. Young animals are 22 to 29 centimeters long at birth with a body mass of 6 to 14 grams. The species reaches a body length of 30 centimeters in the first year. Since she does not survive long in captivity, the average and maximum age are unknown.

Biology and way of life

The species is particularly well adapted to life in the open water ( pelagic ) marine habitats and is found mainly in the Neritian province . The morphological adaptations include a laterally compressed body, a paddle-shaped tail for swimming, closable nostrils and a special soft palate to prevent the ingress of seawater. In addition, the platelet snake has the possibility of gas exchange through the skin, which helps to extend the diving time. Like all Hydrophiinae, it has a special salt gland on the lower jaw, which, contrary to earlier assumptions, does not serve to remove salt from the seawater, since the animals only drink fresh water.

Although the species can remain active up to about 18 ° C, it is dependent on water temperatures above 20 ° C for successful reproduction. The upper temperature threshold is 33.5 ° C to 36 ° C. If the animals were able to acclimate themselves by slowly warming them up, they could withstand temperatures of up to 39 ° C for a short time, although they became hyperactive above 36 ° C. Below 16 ° C water temperature the species loses its ability to move, below 23 ° C there is virtually no food intake.

The species prefers the open water and does not come to the coast voluntarily, it is almost immobile on land due to the oar tail. Occasionally, under special conditions, larger accumulations are washed up on the beaches, where they perish. However, it usually rarely occurs in the open ocean, but prefers waters with a maximum depth of about 100 meters. It is the only sea snake species that prefers habitats away from the shore. Due to its special way of life, it was called the only planktonic vertebrate species.

The platelet snake can be very common in suitable habitats. Spectacular mass gatherings of thousands of individuals have already been observed from ships, mostly in floating debris. Apart from this, the animals are usually only observed sporadically. Since no targeted swimming movements towards such areas were found, passive accumulation in calm, low-current water is assumed.

nutrition

The platelet snake feeds on fish. It hunts from the surface of the water as a lurker. The animals often hide in calm water between floating debris. The snakes wait motionless to catch fish swimming close by with a sudden sideways movement of their heads. The fish are devoured, head first. The hunt takes place almost exclusively during the day, so that the visual sense probably plays a role; however, a great contribution from the chemical sense and water movements is assumed. Although specialized fish eater, studies of the stomach contents showed neither a preference for certain fish species nor for special size classes, but larvae and juveniles predominate. The teeth of the animals are developed in such a way that they hold the prey with all their teeth. The rather poorly developed fangs hardly act as fangs.

Although the species only hunts on the surface of the sea, most of the time, up to 95 percent, it lives submerged. The animals swim with sideways meandering movements to depths of 30 to 50 meters, usually not to the sea floor, in order to reappear slowly and in an elongated path. When there is no hunting activity, such as at night, they only emerge for 1 to 2 minutes to catch their breath. Most dives do not exceed 90 minutes. It is not entirely clear why the animals submerge; presumably they avoid unfavorable conditions on the sea surface, such as the impact of waves or excessively high temperatures.

Poisonous effect

The poison has a neurotoxic effect , through postsynaptic paralysis of muscle activity. Fish that have been bitten are usually killed within a minute. The main poisons are peptides of about 55 to 60 amino acids with a molecular mass of 6000 to 11700. The LD50 in the mouse model was 0.18 to 0.44 micrograms per kilogram of body weight intravenously or 0.67 mg per kg subcutaneously . In another study, 0.15 mg per kg was enough to kill 99 percent of laboratory mice. For humans, LD25 of 3.7 mg per kg (with 45 kg body mass) up to 7.5 mg per kg (with 91 kg body mass) are given. Since a single bite applies a poison dose of 0.9 to 5 mg (depending on the size of the snake), the danger for humans is lower than with other sea snake species. Although fatal bites have been reported, mostly anecdotal, in people who have been bitten, only mild symptoms such as swelling and muscle pain, sometimes muscle paralysis or ptosis of an eyelid have been reported.

Phylogeny

The species was first described by Carl von Linné as Anguis platura and transferred to the monotypical genus Pelamis by François-Marie Daudin in 1803 . There are numerous synonyms. According to recent phylogenomic investigations (based on the comparison of homologous DNA sequences) the species is a morphologically somewhat different representative of the species-rich genus Hydrophis and is therefore now included in this genus. Despite the huge distribution area, the species showed no genetic breakdown by geographic region.

literature

- Carl H. Ernst, Evelyn M. Ernst: Venomous Reptiles of the United States, Canada, and Northern Mexico. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, ISBN 978 0801898754 . Pelamis platura , Yellow-bellied Seasnake, Serpiente del Mar on pages 135–148.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Arne Redsted Rasmussen, Kate Laura Sanders, Michael L. Guinea, Andrew P. Amey: Sea snakes in Australian waters (Serpentes: subfamilies Hydrophiinae and Laticaudinae) -a review with an updated identification key . In: Zootaxa . 3869, January 1, 2014, ISSN 1175-5334 , pp. 351-371. doi : 10.11646 / zootaxa.3869.4.1 . PMID 25283923 .

- ^ A b George V. Pickwell, Wendy A. Culotta (1980): Pelamis Daudin, Pelamis platurus Linnaeus. Pelagic or yellow-bellied sea snake. Catalog of American Amphibians and Reptiles 255: 1-4.

- ^ A b Peter Mirtschin, Arne Rasmussen, Scott Weinstein: Australia's Dangerous Snakes: Identification, Biology and Envenoming. Csiro Publishing, 2017. ISBN 978 0643106741 . Hydrophis platurus on pages 173–175.

- ↑ Mohsen Rezaie-Atagholipour, Parviz Ghezellou, Majid Askari Hesni, Seyyed Mohammad Hashem Dakhteh, Hooman Ahmadian, Nicolas Vidal (2016): Sea snakes (Elapidae, Hydrophiinae) in their westernmost extent: an updated and illustrated checklist and key to the species in the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. ZooKeys 622: 129-164. doi: 10.3897 / zookeys.622.9939

- ↑ Brooke L. Obsessed, Gary J. Galbreath (2017): A new subspecies of sea snake, Hydrophis platurus xanthos, from Golfo Dulce, Costa Rica. ZooKeys 686: 109-123. doi: 10.3897 / zookeys.686.12682

- ↑ a b c Max K. Hecht, Chaim Kropach, Bessie M. Hecht (1974): Distribution of the Yellow-Bellied Sea Snake, Pelamis platurus, and its Significance in Relation to the Fossil Record. Herpetologica 30 (4): 387-396. JSTOR 3891437

- ↑ Harvey B. Lillywhite, Coleman M. Sheehy III, Harold Heatwole, François Brischoux, David W. Steadman (2017): Why Are There No Sea Snakes in the Atlantic? BioScience 68: 15-24. doi: 10.1093 / biosci / bix132

- ^ Carl H. Ernst, Evelyn M. Ernst: Venomous Reptiles of the United States, Canada, and Northern Mexico. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, ISBN 978 0801898754 . on pages 142–143.

- ↑ Kate L. Sanders, Arne R. Rasmussen, Johan Elmberg: Independent Innovation in the Evolution of Paddle-Shaped Tails in Viviparous Sea Snakes (Elapidae: Hydrophiinae) . In: Integrative and Comparative Biology . 52, No. 2, August 1, 2012, ISSN 1540-7063 , pp. 311-320. doi : 10.1093 / icb / ics066 . PMID 22634358 .

- ^ F. Aubret, R. Shine: The origin of evolutionary innovations: locomotor consequences of tail shape in aquatic snakes . In: Functional Ecology . 22, No. 2, April 1, 2008, ISSN 1365-2435 , pp. 317-322. doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-2435.2007.01359.x .

- ^ Roger S. Seymour: How sea snakes may avoid the bends . In: Nature . 250, No. 5466, Aug 9, 1974, pp. 489-490. doi : 10.1038 / 250489a0 .

- ^ William A. Dunson, Randall K. Packer, Margaret K. Dunson: Sea Snakes: An Unusual Salt Gland under the Tongue . In: Science . 173, No. 3995, Jan. 1, 1971, pp. 437-441. doi : 10.1126 / science.173.3995.437 . PMID 17770448 .

- ^ The Sad Tale of the Thirsty, Dehydrated Sea Snake . March 18, 2014.

- ^ Mariana MPB Fuentes, Mark Hamann, Vimoksalehi Lukoschek (2012): Marine Reptiles. In A Marine Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Report Card for Australia 2012 (Eitors ES Poloczanska, AJ Hobday and AJ Richardson). http://www.oceanclimatechange.org.au . ISBN 978-0-643-10928-5

- ↑ Harvey B. Lillywhite, Coleman M. Sheehy III, François Brischoux, Josef B. Pfaller (2015): On the Abundance of a Pelagic Sea Snake. Journal of Herpetology 49 (2): 184-189.

- ^ Carl H. Ernst, Evelyn M. Ernst: Venomous Reptiles of the United States, Canada, and Northern Mexico. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, ISBN 978 0801898754 . on page 144.

- ↑ Timothee R. Cook, François Brischoux (2014): Why does the only 'planktonic tetrapod' dive? Determinants of diving behavior in a marine ectotherm. Animal Behavior 98: 113-123. DOI: 10.1016 / y.anbehav.2014.09.018

- ^ Carl H. Ernst, Evelyn M. Ernst: Venomous Reptiles of the United States, Canada, and Northern Mexico. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011, ISBN 978 0801898754 . on pages 145–146.

- ↑ cf. Hydrophis platurus . The Reptile Database, accessed July 12, 2018.

- ↑ Kanishka DB Ukuwela, Michael SY Lee, Arne R. Rasmussen (2016): Evaluating the drivers of Indo-Pacific biodiversity: speciation and dispersal of sea snakes (Elapidae: Hydrophiinae). Journal of Biogeography 43: 243-255. doi: 10.1111 / jbi.12636