Preacher Monastery Zurich

The Predigerkloster was a Dominican monastery within the city walls of Zurich . It was first mentioned in 1231 and abolished in 1524 on the occasion of the Reformation . It belonged to the Teutonia Order .

history

The preacher monastery in Zurich was one of the first Dominican monasteries in the region. It was created at a time when tensions arose between the aspiring city, which had been free from the empire since 1218, and the claims to power of the Fraumünster Abbey and the Grossmünster Monastery . With the support of the Bishop of Constance , the spiritual foundations refused to make a financial contribution to the construction of the city wall in 1230. The city therefore supported the mendicant orders popular at the time by assigning them free building sites on the outskirts of the city and asking them in return to help build the new city wall. According to the Zurich chronicler Heinrich Brennwald, the first Dominicans in Zurich lived in the Stadelhof suburb around 1230. In 1231 it was mentioned for the first time that a new monastery was being built in Zurich and in 1232 there was evidence of a sale of land at the preacher's court to Prior Hugo von Ripelin († 1270), who apparently was the first to head the monastery. A deed of incorporation has not survived. In a Tösser indulgence directory from the middle of the 14th century, it is mentioned that the Zurich convent was founded on St. Mark's Day in 1233. But this probably means the admission of the Zurich Convention to the Dominican order.

The establishment of the Zurich community probably falls in 1230, as Brennwald reports, and in the following year the monks moved to the city with the support of the citizens. The monastery consisted of a Romanesque church in the same place as the current preacher's church. The three-winged monastery complex was connected to the north of the church. In 1231 the preachers' convention is mentioned for the first time in a papal charter, from which it emerges that the Dominicans had to face strong resistance from the established urban clergy. In any case, the arrival of the Dominicans in Zurich seems to have marked an important step in the urban striving for autonomy, as the city was thus able to emancipate itself in pastoral care from the established monasteries and the diocese of Constance.

In the 13th century, the Dominican Order also founded the Oetenbach convent on the Sihlbühl in Zurich . The founding of the Dominican monasteries in Constance , Bern , Chur and Zofingen also began in Zurich. 1254 strengthened Pope Honorius III. the position of the Dominicans by allowing the preacher's monastery to build a cemetery. Funeral masses and memorial masses had to be held in the Grossmünster until the 14th century, because most of the income was associated with them. Up until the Reformation, a quarter of all income from funerals and funeral celebrations had to be turned over to the Grossmünster. Provincial chapters were held in Zurich in 1280, 1413 and 1463. The order gradually bought 28 houses on today's Zähringer and Predigerplatz.

As early as the 13th and beginning of the 14th centuries, the Zurich Dominicans emphasized the aristocratic-clerical character of their convent and were in close contact with the city and country nobility of Zurich and the surrounding area. In this way they became the cultural bearers of the courtly patrician culture as well as an instrument of power for the elites. Because of its large meeting area, the Zurich Preachers' Convention also had an impact almost all over German-speaking Switzerland. The Dominican Order also made an important contribution to the pastoral care of women through the monasteries of Oetenbach and Töss and through the socially heterogeneous, purely urban women's communities of the Beguines . They lived in Zurich at the preachers' and barefoot monasteries in separate quarters outside the monasteries. The first printing works in Zurich worked in the preacher's monastery. The type caster and printer Sigmund Rot (around 1450 - after 1490) from Lorraine worked under the direction of the learned Dominican Albert von Weissenstein ( Albertus de Albo Lapide , around 1430 - around 1479) . Between 1479 and 1481 he printed 14 small publications here, mostly single-sheet prints (letters of indulgence, calendars and horoscopes) and a Latin explanation of the Salve Regina singing .

The appointment district of Zurich Dominican included after the establishment of monasteries in Basel, Constance and Lausanne the bishoprics customs and Chur , close to the border areas in the Black Forest and Klettgau and now located in Switzerland regions of the Bishopric of Constance, with the exception of today's cantons Schaffhausen, both Appenzell Thurgau as well as the areas of the Prince Abbey of St. Gallen and the Vogtei Rheintal. After the founding of the convents in Bern, Chur and Zofingen, the canton of Zurich, the county of Baden, the Freiamt, Obwalden, Nidwalden, Zug, the county of Uznach, parts of Glarus, Uri and the Gasterland as well as areas near the border in the Black Forest and Klettgau im Zurich Term District.

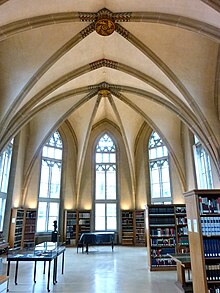

The monastery church was rebuilt in the first half of the 14th century and the choir was rebuilt between 1308 and 1350 at an unusual height for Zurich, so that it towers above the entire quarter. It is considered the most important high Gothic building in Zurich. In 1503 another organ was installed. Little is known about the interior of the monastery church before the Reformation. In Zurich, too, the rapid increase in power of the poverty movement led by the Dominicans soon led to conflicts with the city authorities, because the mendicant orders soon gave up their lack of property. As soon as the preachers in Zurich had their own property and income, they were just as competitive for the council as the established monasteries Fraumünster and Grossmünster. The influence of the Dominicans in Zurich dwindled as early as the 14th century, because the city itself set up social welfare. For this reason, the preachers within the city were soon reduced to the function of local pastors and on December 3, 1524, the preachers' convention was finally completely abolished in the course of the Zurich Reformation. The last monks moved to the barefoot monastery. The service in the church was discontinued, the buildings and income of the monastery were assigned to the neighboring Zurich Heilig-Geist-Spital.

The preacher's church after 1524

The monastery church was initially used as a trot by the hospital. Various modifications were made in 1541/1542, including a partition wall between the choir and the nave. The choir was then subdivided by moving in five intermediate floors so that from 1544-1607 services could be held again for the residents of the Niederdorf on the ground floor . The pastor of the "Preachers" was first placed under the Grossmünster parish and in 1571 was elevated to the rank of Grossmünster canon. In 1575 he was given permission to share the sacrament . The upper floors of the choir served as a grain chute.

On January 21, 1607, the Zurich council decided to move the church service to the separate nave and therefore had it rebuilt and renovated in the Baroque style. A wooden barrel vault was drawn in and the walls and vaults were covered with stucco. The Lichtgaden and the roof structure were raised and a magnificent portal with a vestibule was added on the south side. In 1614 the Predigerkirche was raised to an independent parish and formed the parish Predigern, to which the Neumarkt and Niederdorf guards within the city as well as the communities Oberstrass , Unterstrass and Fluntern were assigned. In 1648 the community had a new gallery built. Shortly afterwards, in 1663, large buttresses had to be added on the south side because the stability of the building seemed questionable due to the additional weight of the newly built barrel vault.

The choir was used for storage purposes in various ways in the 19th century and served as a cantonal and university library from 1803. In 1917 the canton library was moved from the choir and the floors torn out, but in 1919 it was pulled in again to make room for the state archive. Today the premises are used for the central library, especially its music department .

In 1799 the church was opened for Catholic worship, but was converted back into a reformed church on October 17, 1801. When the convent building burned down in 1887, part of the roof structure burned down, but the church was saved from the flames. The biggest structural changes during this time were new windows that were broken out in 1899, a new portal on the west side of the nave in the neo-Gothic style and the 97 m high tower, which was built by Friedrich Wehrli from 1898–1900 according to plans by Gustav Gull . It has a five-part bell that was cast by the company H. Rüetschi , Aarau in 1900. On October 11, 1900, the bells in the tower were raised.

The church has been owned by the parish preachers since 1897. It was renovated in the 1960s and reopened in 1967. Today it is used as an open city church with an ecumenical profile.

The Prediger-Friedhof on Zähringerstrasse was closed in 1843 and exchanged for an area on the Hohen Promenade .

View from the Karlsturm of the Grossmünster

Organs

Main organ

The organ on the gallery was built in 1970 by Orgelbau Kuhn . The slider chest instrument has 46 stops on three manuals and a pedal . The action actions are mechanical, the stop actions are electro-pneumatic.

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coupling : I / II, III / I, III / II, I / P, II / P, III / P

Choir organ

In 2015, an English choir organ, built by James Conacher in Huddersfield in 1886 , was installed in the Methodist Church of Ingbirchworth (Northern England) until 2012 . After a few extensions it comprises 15 registers on two manuals and pedal.

Convent building

The former convent buildings were also used by the hospital after the monastery was closed. After the construction of the new canton hospital in 1842, they became a "supply institution", where the chronically ill, the elderly, the incurably insane, etc. were accommodated. Even contemporaries complained of untenable conditions, which could only be ended by moving into Burghölzli in 1870. The buildings were sold to the city of Zurich in 1873, which used them to accommodate poor citizens. On June 25, 1887, the old convent buildings burned down. Only the preacher church could be saved. The ruins were removed in 1887 and the meadow was used for local festivals in the following years. On June 28, 1914, the Zurich electorate approved the construction of the Zurich Central Library on the building site, which was completed by 1917 according to Hermann Fietz's plans .

See also

literature

- Walter Baumann: Zurich's churches, monasteries and chapels up to the Reformation. NZZ, Zurich 1994.

- Konrad Escher: The art monuments of the canton of Zurich. Vol. IV, The City of Zurich. First part . Birkhäuser, Basel 1939.

- Cordula M. Kessler, Christine Sauer: On book illumination in the vicinity of the Zurich Dominican monastery . - In: Mendicant Orders, Brotherhoods and Beguines in Zurich: Urban Culture and Salvation in the Middle Ages , ed. by Barbara Helbling u. a. - Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 2002, pp. 132–150. - ISBN 3-85823-970-4 .

- Fred Rihner: Illustrated history of Zurich's old town. Bosch, Aarau 1975.

- Martina Wehrli-Johns: History of the Zurich Preachers' Convention (1230–1524). Mendicantism between church, nobility and city. Hans Rohr, Zurich 1980.

- Martina Wehrli-Johns: Study and pastoral care in the preacher monastery . - In: Mendicant Orders, Brotherhoods and Beguines in Zurich: Urban Culture and Salvation in the Middle Ages , ed. by Barbara Helbling u. a. - Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 2002, pp. 106–119. - ISBN 3-85823-970-4 .

- Dölf Wild: On the building history of the Zurich Preachers' Convention . - In: Mendicant Orders, Brotherhoods and Beguines in Zurich: Urban Culture and Salvation in the Middle Ages , ed. by Barbara Helbling u. a. - Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 2002, pp. 91–105. - ISBN 3-85823-970-4 .

- Dölf Wild, Urs Jäggin: The Predigerkirche in Zurich. (Swiss Art Guide, No. 759, Series 76). Ed. Society for Swiss Art History GSK. Bern 2004, ISBN 978-3-85782-759-4 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Baumann: Zürichs Kirchen , p. 76f .; 82.

- ^ Wehrli-Johns: History of the Zürcher Predigerkonvents , p. 10f.

- ↑ a b c Escher: Kunstdenkmäler , p. 207.

- ^ Wehrli-Johns: History of the Zürcher Predigerkonvents , pp. 12, 229.

- ^ Baumann: Zürichs Kirchen , p. 78f .; 83.

- ^ Wehrli-Johns: History of the Zürcher Predigerkonvents , p. 229f.

- ↑ Martin Germann: Zurich's first print shop (1479-1481), Predigerkloster ; in: mendicant orders, brotherhoods and beguines in Zurich, urban culture and salvation in the Middle Ages ; ed. by Barbara Helbling u. a .; Verlag NZZ, Zurich 2002, pp. 151–157, ill., With a list of Zurich incunabula.

- ^ Wehrli-Johns: History of the Zürcher Predigerkonvents , p. 153 (map).

- ^ Rihner: Illustrierte Geschichte , pp. 145f.

- ^ Wehrli-Johns: History of the Zürcher Predigerkonvents , p. 230.

- ↑ Escher: Kunstdenkmäler , p. 208.

- ↑ Bells on YouTube. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- ↑ organ portrait on the website of Kuhn Organ Builders, accessed on May 9, 2014.

- ^ Conacher choir organ on the website of the Predigerkirche Zurich, accessed on January 14, 2016.

- ^ Rihner: Illustrierte Geschichte , pp. 143–150.