Töss Monastery

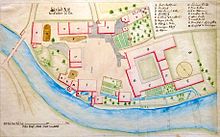

The töss monastery was a convent of Dominican nuns in the 13th century in the Winterthur district Töss . It was canceled at the beginning of the 19th century. The Rieter machine works now stands in its place .

history

Beginning

In the "In den Wyden" area there was a sister house and a mill as early as the 13th century. The Töss Monastery was founded on December 19, 1233 with the approval of the Bishop of Constance by Count Hartmann IV and V of Kyburg . In 1234 a house was first built for the sisters, in 1240 a chapel. Both buildings were consecrated in 1240 by Bishop Heinrich von Tanne .

The church, an elongated single-nave structure with a length of 44.5 meters, was consecrated in 1315. The large pointed arch window on the east wall was probably walled up in 1704. The long south side was pierced by two pointed arch windows, the north side by eight. On the west side, probably only since 1704, there was a small entrance chapel, above it three windows with high Gothic tracery . Nothing is known about the interior of the church; it was probably spanned by a flat wooden ceiling.

A mill by the former bridge over the Töss and a farm formed the first basis of its economic existence. In addition, the monastery was exempt from all taxes and duties. The nuns were given the right to choose their prioress freely.

The vows that the sisters had to take on entry differed only slightly from that of the Oetenbach monastery in Zurich; for both the rules of St. Augustine were authoritative .

After 1235, the monastery was under the orders of Pope Gregory IX. the supervision of the Zurich Dominicans . They preached on high holidays and made confession. In 1268 the Dominican scholar Albertus Magnus paid a visit to the monastery and consecrated the altars of the church. Also Meister Eckhart visited probably in 1324 the monastery. His student Heinrich Seuse often traveled to Töss.

Monastery life and mysticism

A description by Walter Muschg gives an insight into the life of the nuns in the monasteries Oetenbach and Töss :

“The seven canonical times of the day, the Horen , gave the days an unalterably uniform course. They consisted of common prayers with singing and readings in the church choir. The interim times were filled by domestic work in the Werkhaus, especially spinning, and just another type of worship. The more highly educated they spent copying books and sheet music for choral singing. During the meals, which, like the hours in the Werkhaus, went on in silence and were so meager that novices were sometimes disgusted with the food, the reading master read aloud. Heavy fasting commandments from time to time almost completely nullified this refreshment. Lay sisters and children sat at table next to young and very old nuns. Among the women in the Tösser sister book are those who entered the monastery at the age of three, four or six. There you can also find out the zeal with which the cruel regulations were exceeded in the 13th century. During the day, it is said, there was dead silence, no one drove special works, everyone sat in the Werkhaus as devoutly as in the mass. A peculiarity of the preacher's monasteries was still the Matutin , the nocturnal choir before dawn, whose punctual pause was a matter of the heart for the enthusiasts. Some of them can be seen watching through the hours until the prim , the next hour , in the dark choir of the monastery church. This is the time of their most secret experiences, the ecstatic exercises, temptations and visions: "

This atmosphere of great privation promoted the climate of mystical thought; Through long immersion in the world of faith, asceticism and physical mortification, a union with Christ was sought. In the 14th century, the Töss monastery was one of the strongholds of mysticism and the nuns of Oetenbach and Töss are considered to be masters of these exercises with which the soul should be led to God.

The Tösser sister book from around 1340 reports on this life , which in 34 Viten offers a far-reaching insight into the world of the Tösser women's mysticism . It was written by the nun Elsbeth Stagel , who was born shortly after 1300 in Zurich as the daughter of a Zurich councilor and came to Töss as a child , together with a number of sisters who are not known by name . In a mixture of short vitae and more detailed representations, the book draws on different source material, possibly also on some originally independent vitae of grace , for example in the vita of Mechthild von Stans. The book closes with the vita of the Hungarian king's daughter Elisabeth of Hungary , which was added later . Overall, like all sister books, the work conveys less a realistic depiction of everyday life than instruction in religious issues and in the ideals of monastic spirituality. In this sense, the reception took place in the 15th century, when the monastery reformer Johannes Meyer added a foreword to use the book for the objectives of the monastery reform.

Heyday

After the death of the founder of the monastery, who died in 1264 without a direct heir, his possessions came to Rudolf von Habsburg . In 1424 the county first came as a pledge, and in 1452 definitively to the city of Zurich.

The monastery was particularly popular with members of the landed aristocracy and the city council and patrician families. Admission presupposed a certain ability; as a result, the monastery acquired considerable property through donations and purchases. Around 1300 it was the richest monastery in the region. The monastery owned large parts of the village of Töss, the village of Dättlikon , the mills along the Töss as well as large properties in Neunforn , near Rorbas , Buch and Berg am Irchel . The property in the city of Zurich was administered by a separate bailiff. Numerous serfs were also subordinate to the monastery; its first documentary confirmation dates from 1274.

In its heyday in the late 13th and 14th centuries, over a hundred nuns lived in the monastery. Despite the strict regulations, the monastery was so attractive that the nuns' admission was temporarily restricted. The ties between the Töss monastery and the nobility were strengthened in the 14th century by Elisabeth of Hungary , who lived in Töss from 1309 until her death in 1336. In her honor, the monastery included the Hungarian double cross in its coat of arms, which is still part of the Töss municipal coat of arms.

From 1430, the monastery had castle rights with the city of Winterthur , which were renewed in 1488. In 1514, however, the castle rights no longer existed without a specific reason or decree. Causes could be disputes over the rights to the Eulach , the granted customs exemptions or the ownership rights to the Lindberg and in the Neuwiesen .

Between 1469 and 1491 the good economic conditions allowed the nuns to build a new two-story cloister building and to have the new cloister painted by Hans Haggenberg among others . The rear walls of the cloister were around 40 meters, the inner walls 30 meters. Gerold Meyer von Knonau wrote in his handbook «The Canton of Zurich» in 1844: The cloister with 61 pointed arches adorned with 80 fresco paintings [...], of which in 1837 35 were still well preserved. The founder of the cloister is the nun Clara Egghart , who comes from a patrician family in Constance and who also made it possible for Töss Monastery to purchase land.

Stories from the Old and New Testament were depicted on 160 meters of wall space. The coats of arms and names of nuns and their relatives were recorded in the base zone. The wall paintings were destroyed together with the building in the 19th century, but have survived thanks to traces by Paul Julius Arter (1797–1839), August Corrodi and Johann Conrad Werdmüller .

- Pictures by Johann Conrad Werdmüller from the cloister

Decline

At the beginning, the monastery rules in Töss were designed in such a way that the social differences between the origin of the women were balanced out. During the 15th century, as wealth increased, the rules were relaxed. In 1514 a bull allowed more comfortable clothing to be worn. Individual nuns managed their private assets independently, lived in the monastery as if in a boarding house and kept servants. Some of them recovered from monotonous everyday life in the monastery with relatives or during a “spa stay” in Baden and were apparently not averse to supplementing the cure with “earthly joys”. Nuns left the monastery without permission and the bathing room was also used by non-residents. In addition, the morning mass should no longer be sung, but only read. As in the Oetenbach monastery in Zurich, there was also a gradual decline in customs in the Töss monastery; the rules of the retreat were only observed to a limited extent and piety was lost. But until the Reformation, Töss remained a respected and wealthy monastery.

resolution

Even before the Reformation , the monastery no longer made any major purchases. Under the influence of new ideas, the first nuns left the monastery and asked for the goods they had brought back.

After the Reformation, in Holy Week 1525, the Zurich Council abolished Mass at Zwingli's instigation and replaced it with the Lord's Supper. In June of the same year, angry farmers gathered at the gates of the monastery. They made numerous demands on the Zurich authorities and threatened to destroy the monastery. Looting could be avoided, but Zurich decided to close the monastery. In June an overseer appointed by the council removed pictures and statues of saints. On December 9th, 1525, after almost 300 years of existence, the monastery became the property of the state and became an office. His property was confiscated by the Zurich government and a bailiff was appointed to manage it . In the following years the buildings were used as office buildings.

Some nuns converted to the Reformed faith, some married or were taken in by relatives. Others received some kind of pension from the government. The sister community remained, however, because the sisters of the Töss monastery still documented in 1527. In 1532 over thirty former nuns and around twenty lay sisters are mentioned. The last nun of the Töss Monastery, Katharina von Ulm , died in 1572. From then on, the monastery church served as a parish church .

After the French Revolution around 1800 the monastery buildings were empty. In 1833, 600 years after it was founded, the canton of Zurich abolished all offices and the monastery was auctioned. The entrepreneur Heinrich Rieter (1788–1851) bought the system on July 30, 1833 for 103,000 francs and built his machine factory on the site , most of the buildings were demolished. Rieter bought the church in 1834. It remained there until 1916 and was used as a factory hall because of its height. A former mill building has been preserved between the motorway and the factory, which is now used as a transit center for asylum seekers. In addition, in Töss only the monastery street leading along the machine factory reminds of the former Töss monastery.

See also

literature

- Emanuel Dejung, Richard Zürcher: Art Monuments of Switzerland, Canton of Zurich Volume VI. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel 1952.

- Christian Folini: Katharinental and Töss: Two mystical centers from a socio-historical perspective . Chronos , Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-0340-0841-9 (also dissertation at the University of Freiburg / Schw. 2004).

- Klaus Grubmüller: The vitae of the sisters von Töß and Elsbeth Stagel. Tradition and literary unity. ZfdA 98 (1969), pp. 171-204.

- Heinrich Sulzer, Johann Rudolf Rahn : The Dominican convent Töss . Zurich 1903/1904

- Silvia Volkart: The world of images of the late Middle Ages. The wall paintings in Töss Abbey. With contributions by Heinz Hinrikson and Peter Niederhäuser and drawings by Beat Scheffold. Chronos, Zurich 2011, ISBN 978-3-0340-1059-7 / ISBN 978-3-908050-33-9 (= Winterthur City Library (ed.): New Year's Gazette of the Winterthur City Library , Volume 345).

- Sigmund Widmer : Zurich - a cultural history , volume 3; Artemis Verlag, Zurich 1976.

Web links

- Article in «Tössemer»

- Töss Monastery at Happes.net

- Alfred Häberle: Töss (monastery). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Blog of the Cantonal Archeology Zurich on the excavation of the Töss Monastery

- Wikisource - sister books: Tösser sister book

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans Stadler: Kyburg, Hartmann IV. Von (the elder). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Art Monuments of Switzerland, Canton Zurich Vol. VI .; Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel 1952.

- ^ Sigmund Widmer: Zurich - a cultural history , volume 3; Artemis Verlag, Zurich 1976; P. 54

- ↑ Martina Wehrli-Johns: Mechthild von Stans. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Martina Wehrli-Johns: Elisabeth of Hungary. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Werner Ganz : History of the City of Winterthur . Introduction to its history from the beginning to 1798. In: 292nd New Year's sheet of the Winterthur City Library . Winterthur 1960, p. 236-237 .

- ^ Martin Rohde: Haggenberg, Hans. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Chronos-Verlag

- ^ Henry Müller: From the monastery to the machine factory . In: De Tössemer . June 2009, p. 12 & 13 ( toess.ch [PDF; 2.6 MB ; accessed on August 28, 2017]).