preciosity

As precious and preciousness (of French précieux "noble," "precious," "campy" and préciosité " affectation ", "affectation") were in France since the mid-17th century life, sensations and expressions of extreme or exaggerated Sophistication ; these were previously attributed to the Parisian salon culture , and the terminology was used in particular in the negative name Preziöse for a female audience, which is said to have stood out in the aforementioned way in a most conspicuous manner.

A programmatically acting movement or group of certain women and men were not, however, Precious and Precious. The more recent research, which puts the concept of preciosity in an emancipatory environment, even understands "the precious" as a travesting creation of the literature and literary criticism of their time with Molière's play Les Précieuses ridicules ( The ridiculous prezios , first performed 1659, printed 1660) as a film and pivot. The social and cultural debates of the querelle des femmes and the querelle des anciens et des modern serve as the larger framework in which the term was coined .

Society and culture

Power politics and social change

The background for the concept of preciosity was formed by the civilizing countermovement in France after the brutalization of the Huguenot Wars and the profound change that absolutism under Louis XIII. and Louis XIV. brought with it. The new socio-political arrangement found expression in the formula la cour et la ville (“the court and the city”). While “the court” meant the old nobility who had been trimmed to a befitting appearance in the Louvre and later in Versailles , “the city” referred to the upper middle class and the noblesse de robe , the new type of official nobility. Since the beginning of the 17th century, the two social circles united to the extent that the royal bundling of power weakened their position, and they found an equivalent in cultural development for their political losses. The numerous savoir-vivre literature of the 17th century - for example Eustache de Refuge : Traité de la cour (1616), Nicolas Faret : L'Honnête Homme ou l'art de plaire à la cour (1630), Chevalier de Méré : Les Conversations (1668–1669) and Le Discours (1671–1677) - promoted the alignment of the circles by taming the warlike old nobility by means of instruction in fine manners and helping to ennoble the not yet socially acceptable new nobility.

Under the sign of these socio-educational treatises and the essays by Montaigne , moral discussions began in the 1630s, from which standards for a new social culture in the form of the honnêteté (“righteousness”, “respectability”) grew. Gallant Conduite was peculiar to the image of man that was associated with it : decency, education, propriety, inhibition of the emotions. The honnêteté was accompanied by the requirement to adapt to the most varied of milieus and to artfully please the respective counterpart so that every hurdle in interpersonal dealings had to be overcome. Descartes ' Traité sur les passions de l'âme (1649), in which the overcoming of passions was announced, had an important influence on this ideal . The unconditional renunciation of nature and self-interest should create the amiable and completely socialized person for whom the nobility of education and the nobility of soul and not only the nobility of birth counted.

Social culture and gender relations

In order to meet the obligation to be present at the king's court, the aristocracy was forced to leave its rural domains of rule in the province. This favored the development of aesthetic circles as an expression of the new sociability culture , because numerous aristocratic palaces were built in Paris and, in exchange with bourgeois lifestyles, were transformed into literary salons or ruelle ("Kämmerlein"). Here a cultural striving for refinement unfolded by means of a lot of fashionable pomp, some coquetry and artfully ritualized dances, but above all thanks to literary impromptu performances and witty conversation games. The boundaries of the “ educated nobility ” were drawn by bon sens (“common sense”), who, with a view to social usability, raised the pleasant chat and lightness of style beyond the classical rules above pedantic specialist knowledge. The bourgeois literary critic Jean Chapelain reported in 1638 on the Hôtel de Rambouillet , which set the tone in society until the Fronde in the middle of the 17th century: “ On n'y parle point savamment, mais on y parle raisonnablement, et il n'y a lieu du moons où il y ait plus de bon sens et moins de pedanterie. »(German:“ One does not speak at all taught, but with understanding, and nowhere else in the world is there more bon sens and less pedantry. ”) The Chevalier de Méré formulated this as:“ Ce qu'on appelle estre sçavant n 'y sert que bien peu. »(German:" What one describes as being learned helps very little here. ")

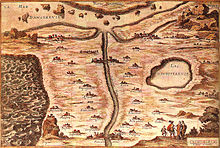

The noble ladies were often the focus of attention in the salons. Catherine de Vivonne in the Hôtel de Rambouillet , then Madeleine de Scudéry with her Samedis (“Saturday receptions ”), the Marquise de Sévigné or Madame de La Fayette brought together the various aristocratic circles with bourgeois authors in the dozen of Parisian circles. The spiritualization of gender relations, cultivated there according to the honnêteté , converted contemporary fantasy maps into images; The Pays de Tendre ("Land of tender affairs") from de Scudéry's novel Clélie, histoire romaine (1654–1660), became famous in its outlines of France . A "kingdom of the precious" is described as follows in the 1650s:

"On s'embarque sur la Rivière de Confidence pour arriver at Port de Chuchoter. De là on passe par Adorable, par Divine, et par Ma Chère, qui sont trois villes sur le grand chemin de Façonnerie qui est la capitale du Royaume. A une lieue de cette ville est un château bien fortifié qu'on appelle gallantry. Ce Château est très noble, ayant pour dépendances plusieurs fiefs, comme Feux cachés, Sentiments tendres et passionnés et Amitiés amoureuses. Il ya auprès deux grandes plaines de Coquetterie, qui sont toutes couvertes d'un côté par les Montagnes de Minauderie et de l'autre par celles de Pruderie. Derrière tout cela est le lac d'Abandon, qui est l'extrémité du Royaume. »

“You embark on the River of Confidence and arrive at the Port of Secrecy. From there, on the way to Überhöflich, the capital of the kingdom, you pass the three cities of Adorable, Divine and My Love. A mile from this town is the well-fortified castle called Galanterie. This castle is very noble and has several outer forts for fiefdoms such as Hidden Fire, Tender Feelings and Flirtatious Friendship. Right next to it are two great levels of coquetry, which are completely enclosed by the mountains of ornament and prudery. Behind all of this is the lake of abandonment at the far end of the kingdom. "

Overall, there was an appreciation of everything feminine in social life, and women achieved a cultural prestige as never before; the number of femmes de lettres was impressive. This development was able to build on an emancipatory debate about the position of women towards men ( querelle des femmes ), which had been going on since the 16th century , in which the same education or the end of forced marriages were demanded on natural law grounds. For the numerous women-friendly pamphlets of this time - as Pierre Le Moyne : Galerie des femmes fortes (1647), Marie de Gournay : Égalité des hommes et de femmes (1662), François Poullain de La Barre : De l'égalité des deux sexes (1673 ) - were the godfathers of the regents Maria de 'Medici and Anna of Austria . The Neoplatonic transfiguration of women as the guardian of order made them the authority on questions of good taste in the salons and allowed them to be associated with preciousness in a special way.

Linguistic and literary developments

Writers and linguists regularly visited the salons. In addition to an artful culture of conversation that produced subtle reflections on aesthetics or love, the salons were also of great importance in view of poetological and linguistic discussions and for the literary culture of France in general. From a circle of the 1620s / 30s, that of Valentin Conrart , the Académie Française emerged in 1635 . The legacy of the time includes both spelling rules and simplifications, as well as under the influence of and in exchange with analogous tendencies in other European countries (marinism in Italy, Gorgonism in Spain or euphuism in England) as well as word creations that aimed for a highly stylized peculiarity. The entertainment requests and interests of the salon visitors contributed to the development of new and to the further development of existing literary genres and genres. Non-canonical small genres are particularly suitable for the demanding conversation game. In addition to the light poetry that Vincent Voiture stood for, there are character portraits , epigrams , aphorisms , maxims , doctrinal conversations , and epistles . A natural, colloquial expression should make it possible to represent the sublime without aplomb and the everyday without platitudes . Paul Pellisson , secretary to the finance minister and patron of Nicolas Fouquet, developed the main idea behind this écriture galante (“gallant style”) . An important representative of this style is Isaac de Benserade .

Lasting effect had the literary experiments and preferences in the salons, not least on the novelistic narrative . Despite the fact that they were subject to learned contempt, exuberant, multi-volume novels found many fans, especially in the aristocratic sphere. There were genres for every taste, such as the shepherd novel of youthful love, the picaresque novel of everyday life or the gallant novel about distant times and countries. The high point of this development was La Princesse de Clèves (1678) by Madame de Lafayette. In a decisive reorientation and in contrast to the pure story novel, the novel of inner sensitivities was created. In the absence of any important social activity, it reflected the nobility's increasingly sensitive self-examination in its reduit, which was formed by the salon and human relationships. The actual textbook of the honnêtes gens (“honorable society”) was created by Honoré d'Urfé in his five thousand page shepherd novel Astrée (1607–1627), which - interspersed with dialogues, letters and poems - was an exuberant arrangement of gallant behavior. However, Madeleine de Scudéry with her novel cycles Clélie and Artamène, ou le grand Cyrus (1649–1653) would later be regarded as the unmistakable author of the preciousness .

Preciousness and Preciousness

Abbé de Pure, Molière and Somaize

|

Summary of the play Les précieuses ridicules

The despotic patriarch Gorgibus wants to finally marry off daughter Magdelon and niece Cathos. Having moved to Paris for this purpose, Magdelon and Cathos want their lives to be like in a gallant novel. Gorgibus doesn't understand a word of what the young women are trying to explain to him verbatim and says in frustration: “ Quel diable de jargon entends-je ici? Voici bien du skin style. »(German:" Devil too, what kind of own talk is that supposed to be? It's probably the high style. ") The first two suitors have already been turned away because they did not advertise for affection after the presentation of the Carte de Tendre , but with the Fell into the house and immediately proposed marriage. Cathos explains to her uncle: “ Je treuve le marriage une chose tout à fait choquante. Comment est-ce qu'on peut souffrir la pensée de coucher contre un homme vraiment nu? »(German:" I find marital status an utterly offensive thing. How can one bear the thought of sleeping side by side with a completely naked man? ") Deeply offended, the spurned disguise their servants as extravagant nobles. They turn the tables in a game of confusion and give the " pecques provinciales " (German: "stupid provincial geese ") to the laughter. The piece ends with a raging Gorgibus who, after all the anger and expenses that Magdelon and Cathos caused him through their coquetry, beats up a group of hired violinists and wishes all the novel-like literature to hell. |

The numerous manifestations of social and cultural refinement and distinction were perceived until the second half of the 17th century without the public baptizing them with a defined term called “Preziosität”. From 1654 women were first described as "precious"; the word had the meaning of socially "respected" or "important". But it remained with individual names, which were mostly appreciative and in the abundance of the printed matter did not attract attention. Among all the short and hardly informative texts, only Abbé Michel de Pures La Précieuse, ou le Mystère des ruelles (1656–1658) stands out. The four-volume novel takes place in the thematic world of the querelle des femmes and describes its fictional, spiritualized heroines as “precious”, but without defining this word à la mode in the course of a winding plot and at the end of a utopian life plan. The work evidently failed and found only a few readers.

Molière's play Les Précieuses ridicules ("The ridiculous precious"), which was first performed on November 18, 1659, was a turning point for public attention . The one-act prosafarce was extremely well received by the audience and was played over forty times within a year. It was so successful that the author Antoine Baudeau de Somaize rolled out the subject in several works and appropriated it for himself, while he accused Molière of having copied from de Pure. Somaize published Le grand dictionnaire des pretieuses (“The great dictionary of the precious”) in 1661 , which also contained a clef de la langue des ruelles (“key to the language of the little chambers ”) that had already been published in the previous year . The Dictionnaire , which is written in the manner of a popular lexicon, designated around four hundred French personalities as agents of preciosity and declared them to be a mass phenomenon. This who's who of social and cultural life is encrypted and follows the world of names and concepts of antiquity. France becomes “Greece”, Paris becomes “Athens”, the Hôtel de Rambouillet becomes the “Palace of the Roselinde”, the Marquise de Sévigné appears as “Sophronie”, Mademoiselle de Scudéry as “Sophie”.

Somaize gave the following description of a precious woman:

«Je suis certain que la premiere partie d'une pretieuse est l'esprit, et que pour porter ce nom il est absolument necessaire qu'une personne en ait ou affecte de paroistre en avoir, ou du moins qu'elle soit persuadée qu ' elle en a. »

"I am certain that the mind is at the forefront of a precious person, and in order to be called a precious person it is absolutely necessary that a person possesses spirit or is able to work spiritually, or at least is convinced of it himself, To possess spirit. "

However, he restricted that not every woman of spirit is also precious:

«Ce sont seulement celles qui se meslent d'escrire ou de corriger ce que les autres escrivent, celles qui font leur principal de la lecture des romans, et surtout cells qui inventent des façons de parler bizarres par leur nouveauté et extraordinaires dans leurs significations. »

“These are only those who care about writing or improving what others write; those for whom the reading of novels is paramount, and especially those who invent strange new idioms that are extraordinary in their importance. "

The clef offered itself as a translation aid for these sayings . It contains many of the expressions and phrases that are typically precious because of their tightness and puffiness, their linguistic artistry and bizarre metaphor, such as les commodités de la conversation (“convenience of conversation”) for the armchair and le conseiller des grâces (“counselor the Graces ”) for the mirror or the salutation ma chère (“ my love ”) and the hyperbolic and stylistically striking adverbs on -ment ( effroyablement, furieusement ).

Formation of literary and literary critical terms

Somaize's Dictionnaire has a literary character and his clef is quoted from Molière's satirical stage prose (as well as from the works of other authors); Nevertheless, these publications became reference works for the subsequently handed down image of a historically effective preciousness in Paris and the French provincial cities. The contemporaries initially made a distinction between the respectable and the ridiculous precious. Molière himself wrote: « … les véritables précieuses auraient tort de se piquer lorsqu'on joue les ridicules qui les imitent mal. »(German:" ... the real precious would be wrongly indignant if you play your game with the ridiculous ones they badly imitate. ") According to Gilles Ménage , the performance met with the approval of high society:

«J'étais à la première représentation le November 18, 1659 des Précieuses ridicules de Molière au Petit-Bourbon . Mademoiselle de Rambouillet y était, Mme de Grignan, tout l'hôtel de Rambouillet, M. Chapelain et plusieurs autres de ma connaissance. La pièce fut jouée avec un applaudissement général… »

“I attended the premiere of Molière's Précieuses ridicules on November 18, 1659 in the Petit-Bourbon . Mademoiselle de Rambouillet was there, Madame de Grignan, the whole Hotel de Rambouillet , Monsieur Chapelain and several others I knew. The performed piece met with general approval ... "

The audience, which might have been offended, apparently recognized the reassuring hint with the names of the two protagonists: Magdelon and Cathos wear pet forms of the first names of Madeleine de Scudéry and Catherine de Vivonne, but they don't want to be like them exemplary salon ladies, but rather “Polyxène” and “Aminte”. In 1690, in his Dictionnaire universel, Antoine Furetière analyzed the term Précieuse in a similar way to Molière:

«Précieuse, est aussi une epithete qu'on a donné cydevant à des filles de grand merite & de grande vertu, qui sçavoient bien le monde & la langue: mais parce que d'autres ont affecté & outré leurs manieres, cela a descrié le mot, & on les a appellées fausses precieuses, ou precieuses ridicules, dont Moliere a fait une Comedie, & de Pures un Roman. On a appellé aussi un mot precieux, un mot factice & affecté, une manner extraordinaire de s'exprimer. »

“'Precious' is also an epithet that used to be given to women of great merit and great virtue, who understood a lot about society and language. But because others adopted an affected and exaggerated demeanor, the word became offensive and they were given the name 'false' or 'ridiculously precious', about which Molière wrote a comedy and de Pure wrote a novel. 'Precious' has also been called a word that is artificial and affected, an unusual way of expressing itself. "

The intensive literary and journalistic preoccupation with the precious lasted until the mid-1660s, Molière's pieces from 1661 to 1663, L'École des maris , L'École des femmes and La Critique de l'École des femmes , held up like the Précieuses ridicules continue to focus on self-determined female education and partner choice. But even after that, precision remained an issue, and its negative typology solidified and simplified with the literary critic and writer Nicolas Boileau . Artificial, inappropriate behavior, screwy choice of words, fashion folly and prudery - all of which were already hinted at or spread out in Molière's mockery - became the main accusations made against the precious. Boileau was a member of the Académie française and had spun a far-reaching network of relationships that he successfully played for his recognition as an aesthetic authority. In the querelle des anciens et des modern , the debate on the exemplary nature of antiquity, he uncompromisingly took sides in favor of the anciens . He judged the novel, which was not intended at all in classical genre poetics , and in particular Madeleine de Scudéry's Le grand Cyrus and Clélie , with malice, calling them “childish” works ( Dialogue des héros de roman , 1668). In exchange with Boileau's literary criticism were his hostile statements about women and the female reading public, the majority of whom preferred the unclassical works of the modern . ( Charles Sorel noted in his Bibliothèque françoise (1664) that predominantly women, courtiers as well as Parisian lawyers and financiers resorted to novels.) His tenth satire (1694), contre les femmes ("against women"), finally broke the Staff over the precious. Boileau declared it survived at the end of the 17th century and Molière was responsible for it.

«…

Une précieuse, leftovers de ces esprits jadis si renowned,

Que d'un coup de son art Molière a diffamés.

De tous leurs sentiments cette noble héritière

Maintient encore ici leur secte façonnière.

C'est chez elle toujours que les fades auteurs

S'en vont se consoler du mépris des lecteurs. »

“.… A precious one,

a relic of these once so well-known figures who brought

Molière's art into disrepute with one blow.

This soulful, noble heiress

preserves her flatterer suite here.

It is to her where all stale authors always

go to find consolation for the scorn of the readers. "

In retrospect, Gilles Ménage also interpreted the premiere of the Précieuses ridicules as a turning point:

“J'en fus si satisfait en mon particulier que je vis dès lors l'effet qu'elle allait produire. […] Au sortir de la Comédie, prenant M. Chapelain par la main: Monsieur, lui dis-je, nous approuvions vous et moi toutes les sottises qui viennent d'être critiquées si finement, et avec tant de bon sens; corn croyez-moi, pour me servir de ce que S. Rémi dit à Clovis; il nous faudra brûler ce que nous avons adoré et adorer ce que nous avons brûlé. Cela arriva comme je l'avais prédit, et dès cette première représentation, l'on revint du galimatias et du style forcé. »

“Personally, I was so satisfied [with the piece] that I immediately saw its effects. […] When I left the comedy, I took Monsieur Chapelain by the hand and said to him: 'Monsieur, you and I, we liked the foolishness that has been criticized with just such sensitivity and good sense; but believe me, to paraphrase the words of St. Remigius to say to Clovis : In the future we must burn what we have worshiped so far and worship what we have burned so far. ' It turned out as I had predicted, and since that first performance one got away from the confusion of words and the screwy style. "

Nicolas Boileau was the last style theorist of the age of Louis XIV and rigorously determined for the following period what belonged to the narrow canon of the grand siècle of French literature and what belonged outside of reception. Since the French Classical period it has been established as a cultural and historical commonplace that after the glamorous times of the unique Hôtel de Rambouillet, preciousness - now without distinguishing between "real" and "false" precious ones - was a ridiculous appearance of provincial-bourgeois self-overestimation and blue-stocked mannerism.

Historical existence

The few descriptions of historical women or men as precious personalities that existed before Molière and Somaize, and the lack of any self-designation in this way, allow neither a typology of the precious or the designation of a precious group of people. Text-critical analyzes of Madeleine Scudéry's works, which are described as precious, even show that her novels also criticized the same distorted will to style that was commonly imagined in the antiprecious distorted images. Due to the limited number of sources, it is impossible to find a really precious literary current; In other words, publications that were aimed at a special audience and clearly differed from the usual écriture galante in terms of form and choice of material . On the contrary, what appeared in antiprecious texts was fictional, precious literature, such as the grotesque quatrain in Les Précieuses ridicules , scene 9:

«Oh! Oh! je n'y prenais pas garde:

Tandis que, sans songer à mal, je vous regarde,

Votre œil en tapinois me dérobe mon cœur.

Au voleur, au voleur, au voleur! »

"Oh! Oh! I no longer

paid attention : When I looked at you without suspicion,

your eyes silently stole my heart from me.

After the thief, after, after! "

This bogus literature was most closely related to the continuations of the bagatelle and impromptu poetry in the Hôtel de Rambouillet . This had lost much of its polish due to its transplantation into epigonal circles. As in the case of the bouts-rimés ( sonnets that had to be completed according to given end rhymes and put on everyone's lips by Ménage), it threatened to degenerate into shallow, merely entertaining verse forging. The best-known bout-rimé , imitated umpteen times in the mid-1650s, dealt with the grief over a dead domestic parrot and everything that has to happen before it is forgotten:

"Plutôt le procureur maudira la chicane,

Le joueur de piquet voudra se voir capot,

Le buveur altéré s'éloignera du pot

Et tout le parlement jugera sans soutane [...]"

"The public prosecutor is more likely to condemn the legal

trick , the card player want to be

muddy , the drunkard stay away from the bottle

and judge the court without official dress [...]"

There were highly refined ways of life, feeling and expression in language use and lifestyle, which are called precious, but could also count as coquetry and poetic gallantry of salon culture; However, there was not the kind of sophistication and exaggeration that Molière and the other authors first appeared or claimed to be writing about from the mid-1650s to the mid-1660s. The two ridiculous provincial women Magdelon and Cathos and their follies served Molière as a starting point for a fundamental criticism, which at the same time also La Rochefoucauld in relation to amour propre (“self-love”) and hypocrisie (“untruthfulness”) as the main driving force behind the decadence of the honnêtes gens developed. Molière's attack on a society caught in the surface and self-sufficient took the way through a social travesty and allusions to the stylistic and thematic work of Gilles Ménage and Paul Pellisson; which ultimately even attacked the patronage of the finance minister Nicolas Fouquet, who surrounded himself in a kind of second royal court with writers and artists like the two mentioned. Molière thus wrote himself in the benevolence of the king, who protected him for the next few years. His play took up a nascent argument between the ruler and his rivals within the government and in the salons. The word “precious”, which was not yet clearly defined by society around 1659, and the emphasis that there were genuine and ludicrous precious things, made the poets innocuous; they dealt with what the French elite had long and broadly concerned about: a number of power struggles as well as disputes over the position of women and the valuation of literary genres. Due to the increasingly important culture, the circles around the femmes de lettres increasingly vied with the court for influence and reputation in society. The royal cultural policy therefore endeavored to eliminate them. This competition is mirrored in the final scene of the Précieuses ridicules ; the once undisputed gentleman in the Gorgibus house rejects the feminine pleasure in reading in a fluff because it has brought his regulated world into complete disorder and his omnipotence has been demystified. The year 1661, when Louis XIV himself took over the rule and eliminated Fouquet, is considered in the French historical division to be the border year between the baroque and classical periods and the, albeit simplistic, ideas contained in these terms of colorful irregularity on the one hand and flawless regularity on the other other.

Starting from the earliest phase of the mention of preciousness, the popular assumption of historical preciousness or its degeneration has persisted to this day despite the corrective research results. Since the mid-1960s at the latest, scientific literature has been denying real existence to the “ridiculous precious ones” and declaring them to be a grotesque caricature of facts; even the “real precious” (at least as a culturally and socially identifiable movement or group with programmatic goals) are now being questioned. In contrast, “precious” and “preciousness” continue to appear as historical scientific terms, but not in the sense handed down from tradition. The accent of the term has shifted away from aesthetic self-stylization towards its emancipatory and early enlightenment environment within French society and literature of the 17th century.

literature

- Renate Baader (Ed.): Molière: Les Précieuses ridicules - The ridiculous precious. Reclam, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-15-000461-6 . (Molière's play in the original language with translation and annotations. In the appendix there are detailed references, an anthology of text excerpts from the works of Madeleine de Scudéry and an afterword on “Molière and the Préciosité”. Scudéry's texts are described as precious in the sense of their extensive emancipatory potential.)

- Roger Duchêne: Les Précieuses ou comment l'esprit vint aux femmes. Fayard, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-213-60702-8 . (Conceptual history of the precious up to the mid-1660s. Several texts by Somaize in the appendix. Preciousness is understood as an awareness of the equality of man and woman.)

- Winfried Engler : History of French Literature at a Glance. Reclam, Stuttgart 2000, pp. 111-177, ISBN 3-15-018032-5 . (Brief remarks on the preciousness, cultural and literary historical background, brief biographies.)

- Jürgen Grimm (ed.): French literary history. JB Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 2006, pp. 162-210, ISBN 978-3-476-02148-9 . (Brief remarks on the preciousness, cultural and literary historical background, brief biographies.)

Web links

The re-evaluation of the preciousness and the questioning of the historical existence of the precious has hardly penetrated the world wide web from the specialist literature. Information available there should therefore be used with due caution.

- Le grand dictionnaire des précieuses ou la clef de la langue des ruelles : Volume 1 , Volume 2 (The dictionary of precious expressions by Antoine Baudeau de Somaize, 1661.)

- Précieuses: L'acte de décès d'une géniale invention (Book review by: Roger Duchêne: Les Précieuses ou comment l'esprit vint aux femmes. )

- Sandrine Aragon: Les images de lectrices dans les textes de fiction français du milieu du XVIIe siècle au milieu du XIXe siècle. (Depiction of the female reading public of the early modern period with a focus on the era of preciousness.)

- La Préciosité en France au XVIIème s. (Website with the traditional representation of the precious and the precious.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ph. Tamizey de Larroque: Lettres de Jean Chapelain de l'Académie française , Imprimerie nationale, Paris 1880-1883, Letter CLI, Volume I, pp. 215-216 (modernized spelling).

- ↑ Winfried Engler: History of French Literature at a Glance . Reclam, Stuttgart 2000, p. 126.

- ^ Marquis de Maulévrier: La Carte du Royaume des Précieuses , written 1654, published in: Charles de Sercy : Recueil des pièces en prose les plus agréables de ce temps , Paris 1658. French quotation from: miscellanees.com, accessed on May 20, 2007 .

- ^ Les précieuses ridicules. Scene 4.

- ^ Les précieuses ridicules. Scene 4.

- ^ Les précieuses ridicules. Scene 1.

- ↑ Antoine Baudeau de Somaize: Le grand dictionnaire des pretieuses - historique, poetique, geographique, cosmographique, cronologique, armoirique où l'on verra leur antiquité, coustumes, devises, eloges, etudes, guerres, heresies, jeux, loix, langage, moeurs , mariages, morale, noblesse; avec leur politique, predictions, questions, richesses, reduits et victoires, comme aussi les noms de ceux et de celles qui ont jusqu'icy inventé des mots précieux. Paris 1661.

- ^ Les précieuses ridicules. Preface.

- ^ Roger Duchêne: Les Précieuses ou comment l'esprit vint aux femmes. P. 204.