August Johann Rösel from Rosenhof

August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof (born March 30, 1705 near Arnstadt , † March 27, 1759 in Nuremberg ) was a German naturalist , miniature painter and engraver . He was a contemporary of the Swedish naturalist Carl von Linné . With his precise, detailed insect depictions, he is considered a pioneer of modern entomology . His grave is in the Johannisfriedhof (Nuremberg) .

youth

Rösel came from an Austrian merchant family who settled in the Nuremberg area at the time of the Reformation . Because of her merits, she was raised again in 1628 by Emperor Ferdinand to the former baron class. Franz Rösel was a painter of animal and forest pieces, his son Pius, the father of August Johann, was a copper engraver and his brother Wilhelm was an animal painter . Pius was appointed administrator of the Augustenburg near Arnstadt by the princess Augusta Dorothea von Arnstadt-Schwarzburg , who also became the godmother of August Johann .

The princess recognized August Johann's talent and promoted his education in painting and science. He first learned in the Merseburg painting workshop of his uncle Wilhelm and then attended the painting academy in Nuremberg . The skills that he soon acquired in copperplate engraving and miniature painting enabled him to travel to Denmark for two years in 1726, where he was even offered a lifelong position at court. He refused this position and returned to Germany, where he got to know the work of Maria Sibylla Merian during a four-week stay in Hamburg . This moved him to deal with the native insect fauna from now on.

Researcher and painter

In 1737 in Nuremberg he married Elisabeth Maria, the daughter of the surgeon, physiologist and poet Michael Bertram Rosa. Rösel's craftsmanship was highly regarded, so that he had a secure income, especially through portraiture, and was also able to concentrate intensively on researching the insect world. He collected larvae and caterpillars, whose development and behavior he carefully studied and recorded in notes and drawings. In 1740 the first edition of his Insecten-Amustigung appeared , a kind of forerunner of today's specialist journals, in 1744 the two-volume edition, which was regularly continued with further deliveries in the following years. In the years 1746, 1749 and 1755 he brought out the previously published works in anthologies. After his death in 1761, a fourth volume was put together by his son-in-law Christian Friedrich Carl Kleemann, who, also a skilled miniature painter, made additions and additions in later editions, such as the nomenclature introduced by Linnaeus .

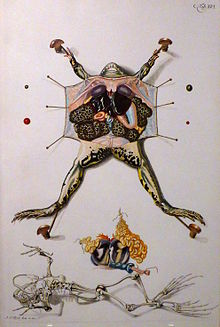

Other works by Rösel were Historia naturalis Ranarum nostratium / The natural history of the frogs in this country , a bilingual table work, the first part of which appeared in 1753 and which was completed in 1758 and for which Albrecht von Haller wrote the foreword. He was unable to complete a planned work on lizards and salamanders before his death. The specialty of August Johann Rösel's work lies on the one hand in the exactness of the representations, which are based on intensive and careful observation. Rösel even learned how to grind lenses in order to be able to make his own observation instruments. On the other hand, in contrast to his contemporaries, he did not depict animals in a purely morphological manner , but tried to describe the way of life and biological processes of his objects of study. His work achieved a very high reputation among other naturalists. Réaumur planned to have his work translated into French, but this was not realized.

At the beginning of 1759, Rösel von Rosenhof suffered a stroke that paralyzed him on one side and died of the consequences on March 27, 1759.

Importance to science

Rösel's representations are often so precise that insect species can be precisely identified using the images; So it is not surprising that one of the most common indigenous long -feeler terrors Roesel's bite-insect ( Metrioptera roeseli ) was named after him.

Even more important for the development of natural research than miniature painting was Rösel's ability to observe and - although he had not studied - his scientific talent: in causal research, he was epistemologically ahead of many scientists of his time. One example is a dispute regarding the origin of meat flies . In the middle of the 18th century, it was still believed that dead meat produced scavenging maggots "out of itself" . After Francesco Redi had already investigated the colonization of meat in 1668 and postulated the laying of eggs as a prerequisite for the larval development of flies, Rösel repeated this attempt.

Here is the original text from Volume II (1749) of his “Insecten-Amustigung”, which is interesting to read, but very typical for the expression of its time.

"Just as there are quite a number of mosquitoes in general to whom this name applies: so the meanest and most well-known among them, which I also often use, is those who want to deny me the natural production of insects, evidently convicting the contrary. These defenders of the old fable that insects arise from putrefaction often used the maggots that are in the old cheese and rotten meat as proof against me, without knowing that they were offering me the right weapons for this very reason to dispute their unfounded opinion. Once I made a bet with some of them that I would not only make myself ambitious to defend their opinion, but also willingly and happily pay the price that was set, if I would not convict them that the rot was too the origin of these maggots would have nothing to do with.

For we chose two completely empty and pure sugar glasses, in each of which a fresh piece of meat, from a four-footed animal, was placed, and then one of them was precisely tied and sealed with delicate parchment or paper; but the other remained open. Now that this had happened, we put both glasses on a closed arbor, in a sunny place, in the open air, and then I claimed that the meat in the closed glass should remain unopened for so long, whole and no maggots could arise; on the other hand everything in the other would soon swarm with them.

When we looked at our glasses the next day, nothing changeable was to be noticed in the closed glass, in the open one, however, we saw not only many eyes lying in layers on the flesh, but also a piece of music that was just busy laying them. On the same day a lot of maggots crept out of these eyes, and in the days that followed, both this and the eyer became more and more numerous, so that they finally covered the flesh completely. The meat in the closed jar, on the other hand, was constantly freed from maggots, whether it was already beginning to rot and finally melted away in murky water.

And therefore at the same time I had the opportunity to show my opponents that the smell arising from the rotten meat lured the mosquitoes, one of which they had already seen in the open glass: then, whether they could not get to the meat itself, let it go they see themselves constantly on the paper with which the glass was closed; yes, even some of them even laid their eyes on it, which, however, had to spoil from lack of necessary food; since, on the other hand, the maggots in the other glass grew larger and larger and completely consumed the meat.

But when my opponents saw this, they gave me the game I had already won, whether I promised them straight away that I wanted to lose the weather too, when I would not convince them further that these maggots were turning into mosquitos like those out of whose eyes they came: only one person would not let go of his old opinion, and objected to me that because of the lack of Lufft, no maggots could have developed from the flesh in the closed glass because nothing could live without Lufft. I alone gave him the freedom to pierce the paper over the glass with a pin at will, so that Lufft would have free access with the assurance that no maggots would arise from it; but without waiting any longer he had to admit to me that the glass itself was still filled with air, and also the same, if not through the paper itself, but through the folds that were there where it was tied, freyen would have access. And so he finally gave himself up as well. "

literature

- Symposium on the 250th anniversary of August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof's death on March 27, 2009, organized by the Natural History Society of Nuremberg and the German Society for Herpetology and Terrarium Studies . Secretary , contributions to the literature and history of herpetology and terrarium science. Vol. 9, issue 2 (2009).

- Armin Geus : Rösel von Rosenhof, August Johann. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 21, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-428-11202-4 , p. 738 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Wilhelm Hess : Rösel von Rosenhof, August Johann . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 29, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1889, p. 188 f.

- Manfred Niekisch: August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof: artist, natural scientist and pioneer of herpetology, an introduction to the reprint of the "Historia naturalis ranarum nostratium - The natural history of the frogs in this country" , 2009 (Historia naturalis ranarum nostratium; vol. 1).

Web links

- Literature by and about August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof in the catalog of the German National Library

- Online version of: Historia Natvralis Ranarvm Nostrativm in qua omnes earum proprietates / The natural history of the frogs here in the region (1758) of the Heidelberg University Library

- Online version of: Insect amusement published monthly by the Heidelberg University Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rösels, AJ Insekten = Amusements, 2 vols. With illum. Image. Nuremberg 1744. in: Directory of the collection of books, oil paintings, copperplate engravings, water and enamel paintings, ... of the postmaster Schustern, who died in Nuremberg, which ... Google Books, online, p. 32, items 35 and 36 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rösel von Rosenhof, August Johann |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German naturalist, miniature painter and engraver |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 30, 1705 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Arnstadt |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 27, 1759 |

| Place of death | Nuremberg |