Richard Lewontin

Richard Charles "Dick" Lewontin (born March 29, 1929 in New York City , † July 4, 2021 in Cambridge , Massachusetts ) was an American evolutionary biologist , geneticist and social critic.

Lewontin was instrumental in developing the mathematical foundations of population genetics and the theory of evolution . He was one of the first to use molecular biology techniques, such as gel electrophoresis , to clarify problems of mutation and evolution. In two essays from 1966, which he published together with JL Hubby (1932-1996) in the journal Genetics , he laid the foundation for modern molecular evolution .

biography

Lewontin attended Forest Hills High School and the Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes in New York. In 1951 he received his BA in biology from Harvard University and a year later his MA in mathematical statistics from Columbia University , followed by a doctorate in zoology . He worked at North Carolina State University , the University of Rochester, and the University of Chicago . In 1965 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

In 1973 he taught as Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology and until 1998 as Professor of Biology at Harvard University and was the Alexander Agassiz Research Professor in 2003.

Lewontin had a great influence on many philosophers of biology such as William C. Wimsatt (* 1941), who taught with him in Chicago, his fellow students Robert Brandon and Elliott Sober , Philip Kitcher and Peter Godfrey-Smith (* 1965). He often invited her to work in his laboratory. Jerry Coyne is one of his most famous students . In 2015 Lewontin was awarded the Crafoord Prize for Life Sciences and in 2017 he was awarded the Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal .

job

Lewontin and his Harvard colleague Stephen Jay Gould criticized the scientific program of "adaptationism" in evolutionary biology in an extremely influential paper. Your writing The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossion paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist program (1979) alludes in the title to the architectural word “spandrel” (“Spandrille”, the gusset between the arches of a vault). Although one might think that these were invented as image carriers for mosaics, they simply inevitably result from the construction method. In the same way, many characteristics of organisms did not exist as the result of a particular, directed adaptation , but would just as easily have emerged as a by-product of other processes. The resulting technical debate about the importance of adaptation for evolution remained fruitful for over 30 years. Together with André Ariew, he later criticized the evolutionary theoretical concept of fitness

Lewontin was an early advocate of a hierarchy of levels of natural selection in his article The Units of Selection . He also emphasized the importance of historicity , i.e. the sequence of past events on evolution, as he wrote in Is Nature Probable or Capricious .

In Organism and Environment in Scientia, and more popularly in the last chapter of Biology as Ideology , Lewontin said that in contrast to the traditional Darwinian representation of the organism as a passive recipient of environmental influences, one should view the organism as the active creator of the environment. Niches are not pre-formed, empty containers into which the organisms are inserted, but are defined and created by the organisms. The relationship between organism and environment is reciprocal and dialectical . MW Feldman, KN Laland and FJ Odling-Smee have developed more detailed models from Lewontin's concept.

Together with other researchers such as Stephen Jay Gould , Lewontin repeatedly criticized sociobiologists such as Edward O. Wilson or Richard Dawkins . For example, a letter from the collective “Science for the People” in the New York Review of Books , which was probably largely authored by Lewontin, was very influential and sparked a debate in the US public about sociobiology that lasted for over 10 years; this became (somewhat pathetically) famous as the “sociobiology wars”. Lewontin's main allegations of sociobiology were a misguided methodology, in particular an exaggerated reductionism and wide-ranging theorizing beyond an empirical, fact-based basis. The debate was also a bitter personal quarrel between Lewontin and EOWilson, which Lewontin had previously encouraged at Harvard University in the early 1970s.

Such concerns about allegedly oversimplification of genetics prompted Lewontin to comment on debates again and again, and he gave many lectures to spread his views on evolutionary biology and science. In his books such as Not in Our Genes (with Steven Rose and Leon J. Kamin ) and numerous articles, he questioned the inheritance of human behavior and intelligence measured in IQ tests , such as those in The Bell Curve by Charles Murray is described.

Some academics criticized Lewontin for his rejection of sociobiology and ascribed this to his political views (Lewontin identified himself at times as a Marxist or at least left-wing; cf. Wilson 1995). Others (such as Kitcher 1985) replied that Lewontin's criticism was based on concerns about discipline. Steven Pinker (2002) thinks that Lewontin attacks a straw man version of sociobiology (or its modern incarnation as evolutionary psychology ) and thus misses the mark. Lewontin's genetic justification for rejecting the concept of race in humans (1972) was criticized professionally and morally by the geneticist and statistician AWF Edwards in 2003 .

Parable of the two fields

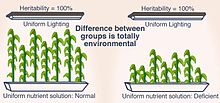

In order to explain why, methodologically correct, measurements of heritability ("heredity") within a group are worthless if one wants to compare two different groups, Lewontin introduced the often cited parable of the two fields: you have a sack full of grains of wheat. Divide this sack in half at random. One half would be sown on fertile soil that was well watered and fertilized. The other half is thrown into a barren field.

If you now look at the first field, you will notice that the ears of wheat are of different sizes. One can trace this back to the genes, because the environment was the same for all ears. If you look at the second field, you will be able to attribute the variation within the field to the genes as well. But it will also be noticeable that there are big differences between the first field and the second field. In the first field the differences are 100% genetic, in the second field the differences are 100% genetic, but that does not mean that the differences between field 1 and field 2 are also genetic.

Lewontin looks at the relationship between social classes in an analogous way. According to Lewontin, a certain percentage of the IQ differences within a stratum could be genetic, but this would not mean that the differences between two strata would also have to be genetic.

Other areas of interest

Lewontin also dealt with the economics of industrial agriculture . He believed that hybrid grain was not developed and promoted because of its better quality, but because it allowed companies to force farmers to buy new seeds each year instead of planting seeds from the previous harvest. He testified in an unsuccessful lawsuit in California that opposed government funding for research to develop automatic tomato harvesters that favored the profit of industrial agriculture over hiring farm workers.

Works

- Is Nature Probable or Capricious? In: Bio Science. Vol. 16, 1966, pp. 25-27.

- The Units of Selection. In: Annual Reviews of Ecology and Systematics. Vol. 1, 1970, pp. 1-18.

- The Apportionment of Human Diversity. In: Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 6, 1972, pp. 391-398.

- The Genetic Basis of Evolutionary Change. Columbia University Press, 1974, ISBN 0-231-03392-3

- Adattamento. In: Enciclopedia Einnaudi. Vol. 1, 1977, pp. 198-214.

- Adaptation. In: Scientific American. Vol. 239, 1978, pp. 212-228.

- The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossion paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist program. In: Proc R Soc Lond B. 205, 1979, pp 581-598 (with SJ Gould).

- Human diversity. 2nd ed. Scientific American Library, 1995, ISBN 0-7167-6013-4 .

- The Organism as Subject and Object of Evolution. In: Scientia. Vol. 188, 1983, pp. 65-82.

- Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology and Human Nature 1984, ISBN 0-394-72888-2 (with Steven Rose and Leon J. Kamin).

- The Dialectical Biologist. Harvard University Press, 1985, ISBN 0-674-20283-X (with Richard Levins).

- Biology as Ideology: The Doctrine of DNA. 1991, ISBN 0-06-097519-9 .

- The Triple Helix: Gene, Organism, and Environment. Harvard University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-674-00159-1 .

literature

- Philip Kitcher: Vaulting Ambition: Sociobiology and the Quest for Human Nature. MIT Press, 1985, ISBN 0-262-11109-8 .

- Steven Pinker : The Blank Slate. The Modern Denial of Human Nature . Penguin, New York 2002, ISBN 0-670-03151-8

- Rama S. Singh, Costas Krimbas, Diane Paul, John Beattie: Thinking about Evolution. Cambridge University Press, 2001 (a two-volume commemorative publication for Lewontin with a complete bibliography).

- Edward O. Wilson : Science and ideology. In: Academic Questions. 8, 1995 ( download ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jerry Coyne: Dick Lewontin, 1929-2021. In: Why Evolution Is True. July 5, 2021, accessed July 5, 2021 .

- ^ Rasmus Nielsen (2009): Adaptionism - 30 years after Gould and Lewontin. Evolution 63 (10): 2487-2490. doi: 10.1111 / j.1558-5646.2009.00799.x

- ↑ Massimo Pigliucci and Jonathan Kaplan (2000): The fall and rise of Dr Pangloss: adaptationism and the Spandrels paper 20 years later. TREE Trends in Ecology and Evolution 15 (2): 66-70.

- ↑ Steven Hecht Orzack & Patrick Forber: Adaptationism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , First published July 22, 2010.

- ↑ André Ariew, RC Lewontin (2004): The Confusions of fitness. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 55 (2): 347-363. doi: 10.1093 / bjps / 55.2.347

- ↑ Allen, E. et al. (1975): 'Against Sociobiology', The New York Review of Books, Nov. 13.

- ↑ Catherine Driscoll: Sociobiology. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy First published November 11, 2013; substantive revision January 16, 2018.

- ↑ Ullica Segerstrale (1986): Colleagues in Conflict: An 'In Vivo' Analysis of the Controversy Sociobiology. Biology and Philosophy 1: 53-87.

- ↑ AWF Edwards, 'Lewontin's Fallacy'

- ↑ How Heritability Misleads about race. The Boston Review, XX, no 6, January, 1996, pp. 30–35 [1]

- ^ Richard C. Lewontin (1970): Race and Intelligence. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 26 (3): 2-8. doi: 10.1080 / 00963402.1970.11457774

Web links

- Interview in Berkeley 2003

- Profile and bibliography

- Hitchcock lecture Gene, Organism and Environment: Bad Metaphors and Good Biology (RealAudio-Stream at UCTV)

- Hitchcock lecture The Concept of Race: The Confusion of Social and Biological Reality (RealAudio-Stream at UCTV)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lewontin, Richard |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lewontin, Richard Charles (full name); Lewontin, Dick (nickname) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American evolutionary biologist and geneticist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 29, 1929 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New York City , USA |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th July 2021 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Cambridge , Massachusetts , USA |