Penuti languages

The Penutian , Penutian or Penutian languages , refers to a controversial macro language family , the many diverse once in the Pacific Northwest and California occurring indigenous American summarizing languages. The associated tribes lived in the area of today's Washington , Oregon and California in the western United States ; there are also isolated representatives in the south of Alaska and in the north-west of British Columbia in Canada .

Their existence was and is still controversial among linguists ; even the individual language groups or subgroups and the affiliation of individual languages were questioned. The problems of comparative linguistics to prove a genetic relationship of the individual languages and thus to summarize them as a maximum genetic unit in a language family are in particular that most of the individual languages in question died out early and / or are poorly documented.

After a conference of American linguists at the University of Oregon in 1994, the classification according to Voegelin & Voegelin (1965), which was also the result of a meeting of several experts at Indiana University Bloomington in 1964, was generally recognized with some extensions and the following language groups or subgroups were classified as genetically related to one another : California-Penuti (also: Core-Penuti) , Coast Oregon-Penuti (sometimes expanded to: Oregon-Penuti), Plateau-Penuti and Chinook .

In the standard classifications (Campbell 1997, Mithun 1999), however, the Penuti language family is rejected.

The Canadian linguist Marie-Lucie Tarpent re-examined the Tsimshian , a geographically isolated language family in northern British Columbia, and concluded that their membership of the Penuti - as already postulated by Edward Sapir - is possible and very likely; however, this is still controversial.

Some of the recently proposed language or subgroups of Penuti - such as Miwok and Ohlone (formerly: Costanoan) - have been convincingly proven to belong; both were also combined in a so-called Utian language family. Catherine Callaghan recently submitted material for a grouping of the Utian languages and the Yokut languages into a Yok Utian (Hotian) language family . In addition, there seems to be convincing evidence of the Plateau Penuti grouping (formerly Shahapwailutan or Lepitan ).

Development of the classification

The hypothetical macro-language family called Penuti or Penutian was originally limited to only five closely related languages in the historic cultural area of California and is therefore now also called Core-Penuti (an), California Penuti (an) or Penuti (an) Kernel . First proposed in 1913 by Roland B. Dixon and Alfred Kroeber , it was established again in 1919 by these two researchers on the basis of the language typology , although such proof of genetic relationship is controversial in linguistics.

- Maidu languages

- Miwok (also: Moquelumnan)

- Costanoan (today: Ohlone)

- Wintu languages

- Yokuts (also: Yokutsan or Mariposa)

Albert Samuel Gatschet had already grouped Miwok and Costanoan together in 1877 in a language family he named Mutsun . Today this language group is known as the Utian languages . With the inclusion of the Yokut , this was expanded by Catherine Callaghan to the so-called Yok-Utian language family .

The term Penutian for this language family is based on two words with the meaning of two in Wintu, Maidu and Yokuts (English pronunciation for example [pen] ) and in Miwok and Ohlone, the so-called Utian languages (English pronunciation for example [uti] ) . Although the pronunciation of Penutian , as some dictionaries suggest, was originally pɛn. imuːtiən in English , it is now pronounced pəˈnuːʃən by most, if not all, linguists . In German, the term penuti is common.

Sapir's extension

In 1916 Edward Sapir expanded Dixons and Kroebers' California Penuti or another branch - the so-called Oregon Penuti , which includes the Coos (Coosan or Kusan) languages as well as the isolated languages called Siuslaw (Šáayušła) and Takelma (Taakelmàʔn) :

-

Oregon Penuti

- Coos (Coosan or Kusan)

- Siuslaw (Šáayušła) (formerly: Lower Umpqua)

- Takelma (Taakelmàʔn)

Later, Sapir and Leo Frachtenberg added the Kalapuya languages as well as the Chinook (Tsinúk) and then the Alsea (Yakonan) and Tsimshian language groups, resulting in Sapir's classification into four branches, published in 1921:

-

I. California Penuti or Core Penuti Branch

- Maidu languages

- Utian (Miwok – Costanoan)

- Wintu languages

- Yokutsan (Yokuts or Mariposa)

-

II. Oregon Penuti Branch

- Coos (Coosan or Kusan)

- Siuslaw (Šáayušła, formerly: Lower Umpqua)

- Takelma (Taakelmàʔn)

- Kalapuya

- Alsea (Yakonan)

- III. Chinook branch (Tsinúk)

- IV. Tsimshian branch

When Sapir published his findings in the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1929 , he had added two more branches:

-

Plateau Penuti Branch

- Klamath – Modoc (also: Modoc, formerly: Lutuami)

-

Waiilatpuan

- Cayuse (now considered an isolated language)

- Molala

- Shahapwailutan or Sahaptian languages (often incorrectly: Sahaptin)

-

Mexico Penuti Branch

- Mixe – Zoque (Mije – Soke)

- Huave (Ombeayiiüts, Umbeyajts)

-

Plateau Penuti Branch

This then resulted in a classification of the Penuti language family into six branches:

- California Penuti or Core Penuti

- Oregon Penuti

- Chinook

- Tsimshian

- Plateau Penuti

- Mexico Penuti

Further extensions

There have also been attempts by other linguists to incorporate other languages into the Penuti language family ( Benjamin Whorf ).

Some proponents have also suggested further connections to other indigenous language families in the so-called Amerind hypothesis - in particular between the Penuti and the likewise hypothetical Hoka (Hokan) and Gulf language families (see: Mary Haas 1951, 1952) ( Joseph Greenberg : Language in the Americas from 1987).

The Amerind , Amerindian or Amerind languages includes, according to the classification of the indigenous languages of the Americas by Greenberg (1987) , all indigenous languages, in addition to the Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dene and heute as isolated language applicable Haida (Xaat KIL) . The Amerindian hypothesis is not accepted by the majority of Americanists and in some contributions it is downright opposed.

Problem of enlargement of the penuti

Using two language examples - the Yuki-Wappo (Yukian) and the Zuñi (Shiwi'ma) - the problem is presented, which arises in the different evaluation of individual languages and their genetic relationship and grouping in language families on the basis of two linguistic schools - the so-called lumpers and splinters (see: Amerindian languages ) - occur:

The small Yuki-Wappo (Yukian) language family, which was once spoken in California and consisted of the Yuki and the Wappo , was also - by Edward Sapir - as part of the Penuti with special kinship to the Yokutsan and the California-Penuti (Core-Penuti) Branch , sometimes considered as part of the Hoka (n) under Sapir's Hokan – Siouan branch or even as geographically isolated Sioux languages . The famous linguist Morris Swadesh (briefly married to the linguist Mary Haas) and creator of the Swadesh list, however, grouped them in his Hokogian language family (together with the Hoka (n) and Gulf languages), including the also highly controversial - mostly used today as a geographical collective name - Coahuilteco (Coahuitecan) language family as well as Chitimacha (Sitimaxa), which is regarded as an isolated language .

In particular, the Zuñi (Zuni or Shiwi'ma) was also proposed as part of the Penuti by Stanley Newman in 1964 (the Penuti hypothesis in relation to the Zuñi was first proposed by Alfred Kroeber and Roland B. Dixon ). Edward Sapir classified it, however, in his famous article in the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1929 as the third branch of his so-called Aztec – Tanoan language family (allegedly consisting of the Kiowa-Tano (Tanoan) and uto-Aztec languages ), which is also not considered convincing later the Zuñi (Shiwi'ma) was removed from the Aztec tanoan (Foster 1996). In addition, it is classified in the current classification of Amerind (see: Joseph Greenberg, Merritt Ruhlen: An Amerind Etymological Dictionary, Stanford University, 2007) as a language that belongs to the Penuti within the Penutian – Hokan branch . In addition, it was either included in the Kiowa-Tano (Tanoan) , Hoka (Hokan) (JP Harrington: "Zuñi Discovered to be Hokan") or the Keres (Keresan) languages (Karl-Heinz Gursky). Today, the Zuni (Shiwi'ma) is usually as isolated language within the historical Pueblo - sprachbund considered that through intensive language contact (which in turn with the local languages five belonged to families) much of its vocabulary borrowed or linguistic structures adopted or passed on; bilingual or multilingualism was widespread among the Pueblo (see: Jane Hill 2002, Campbell and Poser 2008).

Doubt in the middle of the 20th century

Some scholars feared that the similarities between the individual languages within the Penuti or Penutian language family were only due to the adoption of loan words and linguistic structures based on areal language contacts of neighboring tribes and peoples (see: Zuñi (Shiwi'ma) and Tlingit (Lingít Yoo X̲'atángi) and Haida (X̲aat Kíl) ) and were not based on a common original language or proto-language ; In addition, due to the limited available source material (since many languages were or are already extinct), incorrect language analyzes may have been carried out in early comparative linguistics.

Mary Haas commented on this mutual takeover by neighboring tribes and peoples:

“Even where genetic relationship is clearly indicated… the evidence of diffusion of traits from neighboring tribes, related or not, is seen on every hand. This makes the task of determining the validity of the various alleged Hoka (n) languages and the various alleged Penutian languages all the more difficult […] [and] point [s] up once again that diffusional studies are just as important for prehistory as genetic studies and what is even more in need of emphasis, it points up the desirability of pursuing diffusional studies along with genetic studies. This is nowhere more necessary than in the case of the Hokan and Penutian languages wherever they may be found, but particularly in California where they may very well have existed side by side for many millennia. ”

Despite the concerns of Haas and others, at the aforementioned 1964 conference at the University of Indiana at Bloomington, all of Sapir's proposed branches north of Mexico within the Penuti or Penutian language family were retained.

An opposite approach was taken after a conference in 1976 at the State University of New York at Oswego in Oswego by Campbell and Mithun when they rejected Penuti as a language family because they felt it was not sufficiently and convincingly documented; thus Penuti is not listed as a separate language family in their respective standard classifications and is rejected as such by them. (Campbell 1997, Mithun 1999).

Current hypothesis

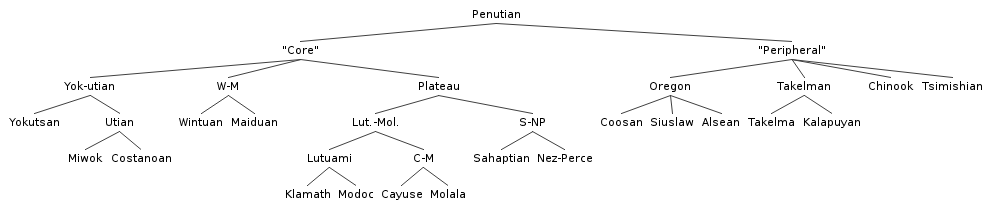

Many penuti linguists no longer accept California-Penuti as well as Takelma-Kalapuya or Takelman as valid terms for regional branches (see California-Penuti) or closely related branches of language (see Takelman). However, the names Plateau-Penuti , Oregon Coast-Penuti and Yok-Utian are increasingly supported. Scott DeLancey therefore suggests the following relationships between and within the individual language families, which are typically included in the Penuti language family.

The Wintu languages, as well as Takelma and Kalapuya , are still regarded by most scholars as Penuti languages, but are often grouped together in an increasingly controversial so-called Oregon Penuti branch ; in addition, it is no longer assumed that Takelma and Kalapuya form a separate Takelma branch of Penuti.

Maritime / Coastal Penuti

I. Tsimshian (Tsmksian) languages (with four varieties )

-

Tsimshian variety (the Tsimshian (Ts'msyan) ) (also: Ts'imsanimḵ, Maritimes Tsimshian, Lower / Northern Tsimshian; formerly: Coastal Tsimshian)

- Coastal Tsimshian or Sm'álgyax / Sm'algax (also: actually Tsimshian)

- Southern Tsimshian or Sgüüx̣s (†)

-

Wet Gitksan variety (also: Binnen-Tsimshian, Inland Tsimshian)

- Nisga'a or Nisg̱a'amḵ (the Nisga'a ) (also: Nisga'a Ts'amiks, Nass, Nisgha, Nisg̱a'a, Nishka, Niska, Nishga, Nisqa'a, sometimes Sim'algax - "True Language" not to be confused with the coastal tsimshian of the same name)

- Gitxsan or Gitxsanimaax (the Gitxsan (Gitksan) ) (also: Gitksanimḵ, Giklsan, Gitksan, Gityskyan)

- Western Gitxsan or Gitsken / Gitsenimx̱

- Eastern Gitxsan or Gitxsanimax̱

II. Chinook (Tsinúk) languages (of the different Chinook peoples)

- Lower Chinook or Tsinúk (also: coastal Chinook, Lower Tsinúk, aka Chinook)

- Clatsop or Tlatsop / Latcap (†)

- Shoalwater or Willapa Chinook (also: Lower Chinook, aka Chinook) (†)

- Chinuk Wawa (Chinook Jargon) (also: Chinook Pidgin, Chinook Lelang; mostly however: called wawa or lelang; a pidgin - commercial language , today partly developed into a Creole language )

- Middle Chinook or Kathlamet (also: Katlamat, Cathlamet, Cathlamette, Cathlamah) (†)

- Kathlamet

- Wahkiakum or Wackiakum (also: Wac-ki-cum, Wahkiaku)

- Upper Chinook or Kiksht (also: Upper Tsinuk, Columbia Chinook or Wasco-Wishram)

- Multnomah or Wapato Chinook (also: Wappato Chinook) (†)

- Kiksht

- Watlalla / Watlala or Cascades (†)

- Clackamas (†)

- Clackamas

- Clowwewalla (also: (Willamette) Falls Indians, Tumwater Falls Indians)

- Hood River (also: Ninuhltidih [Curtis] or Kwikwulit [Mooney]) (†)

- Skilloot or skillot

- Wasco wishram

- Wasco

- Wishram

- White Salmon River or Chilluckittequaw (also: Chiluktkwa) (†)

III. Coast Oregon Penuti / Coast Oregon Penuti languages

-

Alsea or Alsea-Yaquina (also: Alcea, Alse, Yaquina, Yakona, Yakonan) (†)

- Alsea or Alséya

- Yaquina / Yakwina or Yakona

-

Siuslaw (Šáayušła) or Lower Umpqua (†)

- Siuslaw or Šáayušła (also: actually Siuslaw)

- Lower Umpqua or Kuitsh / Quuiič

-

Coos languages (also: Coosan or Kusan) (†)

- Hanis or Coos (also: Kusan, actually Coos, several dialects)

- Miluk or Lower Coquille (two dialects)

IV. Oregon Penuti languages (controversial to this day) (?)

-

Kalapuya languages (with several regional dialect continua ) (†)

-

Northern Kalapuya or Tualatin-Yamhill

- Tualatin or Tfalati / Atfalati

- Yamhill or Yamell / Yamhala

-

Central Kalapuya or Santiam

- Ahantchuyuk

- Chelamela

- Chemapho

- Chepenafa

- Luckiamute

- Santiam

- Tsankupi

- Winefelly-Mohawk (multiple dialects)

- Southern Kalapuya or Yoncalla / Yonkalla

-

Northern Kalapuya or Tualatin-Yamhill

-

Takelma language or Taakelmàʔn (†)

- Upper Takelma or Latgawa

- Lower Takelma or Takelma / Dagelma (also: Lowland Takelma, Tiefland Takelma)

-

Wintu languages or Copeh (also: Wintuan, Wintun, Wintoon, Copehan) (†)

-

Northern Wintu

- Wintu or Wintʰuːh / Wintʰu: h (also: Nördliches Wintu, actually Wintun)

- Nomlaki or Wintun (also: Noamlakee, Central Wintu)

-

Southern Wintu

- Patwin or Southern Wintu (also: Patween)

- River Patwin or Valley Patwin (also: River / Valley Patween)

- Hill Patwin (also: Hill Patween)

- Southern Patwin (also: Southern Patween, considered either as the third dialect of "Patwin / Southern Wintu" or as a separate Wintu language)

- Patwin or Southern Wintu (also: Patween)

-

Northern Wintu

Inland / Inland Penuti

I. Yok Utian languages (also: Hotian, consisting of Yokuts languages and Utian languages, from the Great Basin )

-

Yokuts languages (also: Mariposa, Yokutsan, with several regional dialect continua )

- Poso Creek

- Poso Creek Yokuts or Palewyami Yokuts (also: Altinin) (†)

- Yokuts (also: actually Yokuts)

-

Buena Vista Yokuts (†)

- Tulamni

- Hometwali or Humetwadi

- Tuhohi or Tohohai (also: Tuhohayi)

- Loasau (?)

-

Buena Vista Yokuts (†)

- Nim

-

Tule-Kaweah Yokuts

- Bokninuwad

- Yawdanchi or Nutaa

- Wikchamni or Wukchumni

-

Northern Yokuts

- Gashowu Yokuts or Casson Yokuts

- Kings River Yokuts

- Ayitcha or Kocheyali (also: Aiticha)

- Choynimni or Choinimni

- Chukaymina or Chukaimina

- Michahay or Michahai

- Valley Yokuts (sometimes considered to be three languages)

- Far Northern Valley Yokuts or Delta Yokuts (†)

- Yachikumne or Chulamni

- Chalostaca

- Lakisamni

- Tawalimni or Tawalimnu

- Northern Valley Yokuts (the following dialects are also known as "Northern Hill Dialects": Kechayi, Dumna, Dalinchi, Toltichi and Chukchansi)

- Chawchila or Chauchila

- Chukchansi (the only dialect still spoken)

- Dalinchi

- Dumb

- Kechayi

- Nopṭinṭe

- Toltichi

- Southern Valley Yokuts (†)

- Wechihit

- Nutunutu-Tachi

- Nutunutu

- Tachi

- Chunut or Sumtache

- Wo'lasi – Choynok

- Wo'lasi

- Choynok or Choinok

- Wowol

- Telamni

- Koyeti-Yawelmani

- Koyeti

- Yawelmani or Yowlumne (also: Yowlumni, Yauelmani or Inyana Yaw'lamnin ṭeexil)

- Far Northern Valley Yokuts or Delta Yokuts (†)

-

Tule-Kaweah Yokuts

- Poso Creek

-

Utian languages

-

Miwok languages or Miw yk (also: Miwokan, earlier: Moquelumnan, with two regional dialect continua)

-

Eastern Miwok

- Plains Miwok or Valley Miwok (†)

- Bay Miwok or Saclan / Saklan Miwok (†)

- Sierra Miwok or Plains and Sierra Miwok

- Northern Sierra Miwok or Saclan

- Camanche

- Fiddletown

- Ion

- West Point

- Central Sierra Miwok or Saclan

- East Central Sierra Miwok

- West Central Sierra Miwok

- Southern Sierra Miwok or Yosemite Miwok (also: Meewoc, Mewoc, Me-Wuk, Miwoc, Miwokan, Mokélumne, Moquelumnan, San Raphael, Talatui, Talutu)

- Yosemite

- Mariposa

- Southern dialects

- Northern Sierra Miwok or Saclan

-

Western Miwok

- Coast Miwok or Coast Miwok (†)

- Bodega

- Marin

- Lake Miwok (almost † )

- Coast Miwok or Coast Miwok (†)

-

Eastern Miwok

-

Ohlone languages (formerly: Costanoan)

- Karkin or Carquin Ohlone (also: Los Carquines) (†)

-

Northern Ohlone (also: Northern Costanoan)

- San Francisco Bay Ohlone dialect group

- Chochenyo or East Bay Ohlone (also: Chocheño, Nördliches Ohlone, East Bay Costanoan)

- Ramaytush or San Francisco Ohlone

- Tamyen or Santa Clara Ohlone (also: Tamien, Thamien, Santa Clara Costanoan)

- Awaswas or Santa Cruz Ohlone (possibly several variants)

- Chalon or Soledad Ohlone (also: Cholon, possibly a transit form of Northern and Southern Ohlone)

- San Francisco Bay Ohlone dialect group

-

Southern Ohlone

- Mutsun or San Juan Bautista Ohlone (also: San Juan Bautista Costanoan)

- Rumsen or San Carlos Ohlone (also: Rumsien, Carmel Ohlone, Carmeleno, San Carlos Costanoan)

-

Northern Ohlone (also: Northern Costanoan)

- Karkin or Carquin Ohlone (also: Los Carquines) (†)

-

Miwok languages or Miw yk (also: Miwokan, earlier: Moquelumnan, with two regional dialect continua)

II. Maidu languages (also: Maidun, Maiduan, Pujunan, Meidoo, Holólupai, Michopdo, Nákum, Secumne, Sekumne, Tsamak, Yuba, from the Great Basin or from Oregon )

- Maidu or Májdy (also: Yamonee Maidu, Northeast Maidu, Mountain Maidu, actually Maidu) (possibly † )

- Chico or Valley Maidu (†)

-

Konkow or Koyoomk'awi (also: Nordwestliches Maidu, Concow-Maidu, according to a source at least nine dialects) (almost † )

- Otaki

- Mikchopdo

- Cherokee

- Eskeni

- Pulga

- Nemsu

- Feather Falls

- Challenge

- Bidwell Bar

-

Nisenan or Southern Maidu (also: Neeshenam, Nishinam, Pujuni or Wapumni) (almost † )

- Valley Nisenan

- Northern Hill Nisenan

- Central Hill Nisenan

- Southern Hill Nisenan

III. Plateau Penuti languages

-

Sahaptian (also: Shahapwailutan, formerly incorrectly: Sahaptin)

-

Nez Percé or Niimiipuutímt (also: Nez Perce, Nimipuutímt, Nimiipuutímt, Niimi'ipuutímt)

- Upper Nez Perce or Upper Niimiipuutímt (also: Upriver Nez Perce, Eastern Nez Perce)

- Lower Nez Perce or Lower Niimiipuutímt (also: Downriver Nez Perce, Westliches Nez Perce)

- Weyíiletpuu or Waiilatpu (a variety of the Lower Nez Perce / Lower Niimiipuutímt)

-

Sahaptin languages or Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwit (forms a dialect continuum )

-

Northern Sahaptin

- Northwestern dialect group

- Yakama or Lower Yakama (also: Yakima, actually Yakama, Mámachatpam)

- Kittitas or Upper Yakama (also: Pshwánapam, Pshwanpawam)

- Klickitat or Klikitat (also: Xwálxwaypam)

- Taidnapam or Upper Cowlitz (also: Táytnapam, Taitnapam, Táitinpam, Cowlitz Klickitat, Lewis River Klickitat, often incorrectly: Lewis River Cowlitz, Lewis River Chinook)

- Meshal or Upper Nisqually (also: Me-Schal, Mashel, Mica'l, Mishalpam, Upper Mountain Nisqually)

- Northeastern dialect group

- Wanapum or Wanapam / Wánapam

- Palouse or Palus (also: Pelúuspem)

- Lower Snake River (†)

- Chamnapam

- Wauyukma

- Naxiyampam

- Walla Walla or Waluulapan

- Northwestern dialect group

-

Southern Sahaptin or Columbia River Sahaptin

- Umatilla or Rock Creek (also: Imatalam)

- Skin-pah / Skin or Sawpaw

- Tenino or Warm Springs dialect

- Tygh Valley or Upper Deschutes

- Celilo or Lower Deschutes

- Tenino or Dalles Tenino

- John Day or Dock-Spus / Tukspush

-

Northern Sahaptin

-

Nez Percé or Niimiipuutímt (also: Nez Perce, Nimipuutímt, Nimiipuutímt, Niimi'ipuutímt)

-

Molala or Molele (also: Molalla) (†)

- Northern Molala

- Upper Santiam Molala

- Southern Molala

-

Klamath or Maqlaqsyals (also: Klamath-Modoc, formerly: Lutuamian, Lutuami) (†)

- Klamath or? Ewksiknii

- Modoc or Moowat'aakknii

literature

- H. Aoki. Nez Perce Grammar. Berkeley 1970.

- Berman, Howard (1996). The position of Molala in Plateau Penutian. International Journal of American Linguistics , 62 , 1-30.

- Callaghan, Catherine A. (1967). Miwok-Costanoan as a subfield of Penutian. International Journal of American Linguistics , 33 , 224-227.

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America . New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1 .

- DeLancey, Scott; & Golla, Victor (1997). The Penutian hypothesis: Retrospect and prospect. International Journal of American Linguistics , 63 , 171-202.

- Dixon, Roland R .; & Kroeber, Alfred L. (1903). The native languages of California. American Anthropologist , 5 , 1-26.

- Dixon, Roland R .; & Kroeber, Alfred L. (1913). Relationship of the Indian languages of California. Science , 37 , 225.

- Dixon, Roland R .; & Kroeber, Alfred L. (1913). New linguistic families in California. American Anthropologist , 15 , 647-655.

- Dixon, Roland R .; & Kroeber, Alfred L. (1919). Linguistic families of California (pp. 47-118) Berkeley: University of California.

- Ernst Kausen, The Language Families of the World. Part 2: Africa - Indo-Pacific - Australia - America. Buske, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-87548-656-8 . (Chapter 12)

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1910). The Chumash and Costanoan languages. University of California Publications in American Archeology and Ethnology , 9 , 259-263.

- Mithun, Marianne (1999). The languages of Native North America . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7 (hbk); ISBN 0-521-29875-X .

- B. Rigsby & N. Rude, Sketch of Sahaptin, a Sahaptian Language. Handbook of North American Indians; vol. 17: I. Goddard (ed.), Languages. Washington 1996, 666-692.

- Sapir, Edward (1921). A bird's-eye view of American languages north of Mexico. Science , 54 , 408.

- Sapir, Edward (1929). Central and North American languages. Encyclopaedia Britannica (14th ed .; Vol. 5; pp. 138-141).

- M. Silverstein, Penutian: An Assessment. L. Campbell & M. Mithun (eds.), The Languages of Native America. Austin, Texas 1979, 650-691.

See also

Web links

- Indian languages

- North and Mesoamerican languages

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World English

- First Voices - data and dictionaries for individual languages: Sm'algyax, Sgüüx̱s, Nisg̱a'amḵ, Gitsenimx̱

- Sm'algyax Living Legacy Talking Dictionary

- Sealaska Heritage - Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian Language Dictionaries, Workbooks and Databases

- Gitxsan Language Resources - Dictionaries

- Gitksan Mother Tongues Dictionary

- Gitksan / English ONLINE DICTIONARY (BETA)

- The University of British Columbia - First Nations Languages of British Columbia: Tsimshianic including Sm'algyax (Coast Tsimshian), Nisga'a, and Gitxsan

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dixon & Kroeber 1913A, 1913b

- ^ Joseph Greenberg: Language in the Americas, Publisher: Stanford University Press, June 30, 1987, ISBN 978-0-8047-1315-3 , 456 pages

- ^ Lyle Campbell, William J. Poser: Language Classification: History and Method. Cambridge University Press, June 26, 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-88005-3 .

- ↑ Goddard 1996: 317-320

- ↑ Delancey and Golla 1997

- ↑ Tarpent & Kendall 1998

- ↑ First Voices - Nisgaa language

- ↑ Here Is the Story of GalksiGabin - A Modern Auto-Ethnography of a Nisga'a Man

- ↑ "Columbia Chinook" refers to the language area along the river of the same name and "Wasco-Wishram" to the last dialect still spoken today

- ↑ "Kuitsh / Quuiič (Lower Umpqua)" should not be confused with the "Upper Umpqua language" belonging to the Pacific coast Athapaskan

- ↑ "Miluk (Lower Coquille)" should not be confused with the Tututni dialect "Upper Coquille", which belongs to the Pacific Coast Athapaskan.

- ↑ sometimes the Ohlone languages are only divided into a "Northern branch (including the Karkin)" and a "Southern branch (including the Chalon)"; some linguists classify the eight Ohlone languages only as dialects of a common language

- ↑ Attention: the terms Sahap tian and Sahap tin must be distinguished: "Sahap tin " (denotes the "Sahaptin" languages and the "Sahaptin" peoples who speak them - excluding the Nez Percé) and "Sahap tian " (stands for the language family from Sahaptin languages and the Nez Percé language)

- ↑ the original language of the Cayuse (Liksiyu) is considered an isolated language and is now extinct; the Cayuse had already in the early 19th century by language shift their mother tongue abandoned and the Lower / Downriver Nez Perce adopted

- ↑ the designation as "Upper Cowlitz" often led to confusion or identification with the "Lower Cowlitz" who spoke Cowlitz (Sƛ̕púlmš) - a Southwestern Coast Salish (Tsamosan) language; earlier the "Taidnapam" were considered to be originally ethnic and linguistic "Cowlitz", who would have spoken a variant of this Salish language, but would have given it up in favor of a variant of the Klickitat Sahaptin at the beginning of the 19th century; today the ethnic identity as a Sahaptin-speaking people has been clarified

- ↑ the "Mishalpam (Upper Nisqually)" often married into the downstream Southern Lushootseed (Twulshootseed) -speaking Nisqually (Squalli-Absh / Sqʷaliʼabš) , who belong to the coastal Salish , and began the Sahaptin (their Mother tongue) in favor of Nisqually / Sqʷaliʼabš , at Leschi's time they were partly still bilingual; However, there is also the doctrine that the Mishalpam were originally ethnically and linguistically "Nisqually" and had adopted a variant of the Klickitat Sahaptins by the 19th century at the latest

- ↑ the Skin-pah / Sk'in or Sawpaw are also known as Fall Bridge People and Rock Creek People under the name K'milláma among the Yakama, possibly another name for the Umatilla, also known as the "Rock Creek Indians" were; but often viewed as a Tenino band