Sharing economy

The term sharing economy , more rarely also share economy , is a collective term for companies, business models , platforms , online and offline communities and practices that enable the shared use of fully or partially unused resources .

In addition, the terms collaborative consumption and collaborative economy are used in English-speaking countries .

In its definition of the term, the French network OuiShare emphasizes the characteristics of communal consumption , collaborative production , collaborative finance, open and freely accessible knowledge and horizontal and open administrative structures.

Examples of professional “sharing” concepts have long been known from agriculture . A well-known legal form from this area is the cooperative .

The recent increase in interest in the sharing economy can be attributed in particular to the increased use of information technologies in social networks and electronic marketplaces . Information technology not only enables direct interaction between users and organizations, but also contributes significantly to the scalability and spread of the phenomenon. In addition, social aspects such as consumer behavior and habituation, the appreciation of property or the lack of it, also play a decisive role. Due to the growing interest and the social importance, the Cebit made “Shareconomy” 2013 its main theme.

definition

Different publicists, journalists, companies and protagonists of the sharing economy sometimes understand the term very differently. There is no generally accepted definition or delimitation of the sharing economy. The term is closely related to that of collaborative consumption , which was coined in the context of ride-sharing in the 1970s. The term share economy was used in 1984 by the Harvard economist Martin Weitzman for a book title. The term sharing economy is probably first found in 2008 by Lawrence Lessig , but in the sense of a new paradigm for shared consumption and exchange without money. The origin of the term is therefore controversial.

The publicist Rachel Botsman was one of the first to take a closer look at the phenomenon of the sharing economy as it is today and to popularize it with her book (together with co-author Roo Rogers) and a TED lecture . It distinguishes between three main concepts: redistribution markets (e.g. Ebay ), collaborative lifestyles (e.g. Taskrabbit , BlaBlaCar ) and product-service systems (e.g. Airbnb ). Common to these are the factors of critical mass , free resources, community spirit and trust between unknowns. Botsman defines the term sharing economy as follows:

"The Sharing Economy is an economy built on distributed networks of connected individuals and communities versus centralized institutions, transforming how we can produce, consume, finance, and learn."

Lisa Gansky considers the phenomenon of the sharing economy in the context of a network that is based on decentralized resources brought into a network ( mesh ) by companies and private individuals:

"The Mesh is a model in which consumers have more choices, more tools, more information and more power to guide those choices."

A distinction is made between full mesh and own-to-mesh models. Full meshes are business models in which a central organization offers and manages a resource that is used by many people, such as B. the car sharing providers Zipcar, Car2Go and Stadtmobil. Own-to-Mesh, on the other hand, describes business models in which a central entity only acts as an intermediary in a multi-sided platform market. Examples are Airbnb, Drivy or BlaBlaCar .

Alex Stephany defines the sharing economy as follows:

"The Sharing Economy is the value in underutilized assets and making them accessible online to a community, leading to a reduced need for ownership of those assets."

Interpretations

The allocation to the sharing economy is often not clear. The idea of access over ownership , which relates to ownership and ownership , has been discussed frequently in the literature. More recently, the term has been associated with the theses of the American sociologist Jeremy Rifkin .

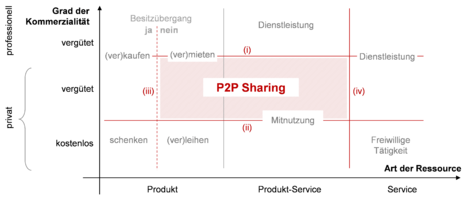

In the scientific literature, the dimensions of degree of commercialism and type of resource ( product / service character), or the criteria (i) non-professionalism , (ii) commercialism , (iii ) are used to classify and delimit sharing economy business models ) Temporality and (iv) Tangibility used. The diagram illustrates the space spanned by the demarcation criteria to which business models of the sharing economy are commonly assigned.

In addition to the mainly microeconomic definitions of the term, the sharing economy is also considered from a macroeconomic point of view. In this context, the sharing economy is seen as a decisive factor in hybrid market models. These are based on the coexistence of classic, transaction-based markets alongside non-market-based models. The subject of research is why consumers participate in the sharing economy, which is located at the interface of both models, and why they may prefer it to conventional models.

One example is the free software movement , which produces and distributes free software . Free software is software that programmers share with the whole world, and everyone has the right to use, inspect, change and redistribute changed versions free of charge. Even open source software is free to use most, with now also business models for open source software developed.

Bookcrossing and public bookshelf are two terms that originally only refer to the exchange of books. In the meantime, other media such as CDs and DVDs are also exchanged in this way. As a library of things borrowed are designated for various objects, such as those offered by other public libraries.

Due to the different definitions, the following five criteria are specified for a sharing economy:

- Online platforms generate added value or have the potential to do so.

- Unused capacities of unused or only partially used resources can be marketed.

- These capacities are generally accessible or can be made accessible.

- The system is operated by an organization, e.g. B. also supported an active and committed community.

- The resource usage in the Community ( access ) changed consumer behavior away from traditional ownership models ( ownership ).

Economic importance of the sharing economy

The sharing economy in the current sense has experienced steadily growing economic importance since its emergence. A study by PwC estimates that global sales for the sharing economy segments travel , car sharing , finance , staffing and music & video streaming will increase from $ 15 billion in 2015 to around US $ 335 billion by 2025 . For the mobility sector, the consulting firm Roland Berger estimates the following global sales potential by 2020: car sharing 3.7–5.6 billion euros, ride sharing 3.5–5.2 billion euros, bike sharing 3.6–5.3 Billion euros and shared parking 1.3–1.9 billion euros.

A common example is Airbnb. The platform has already placed over 200 million guests worldwide. It lists over 3 million advertisements in 65,000 cities or 191 countries worldwide. Based on the latest funding rounds, Airbnb is valued at around $ 25.5 billion. A study for the US state of Texas estimates that a 1% increase in the number of Airbnb listings there causes a 0.05% decrease in hotel sales.

Sharing economy services and platforms now also play a significant role in Germany. In 2015, 14.6 million overnight stays in German cities were brokered via services such as Airbnb, Wimdu and 9flats, which makes up around 9% of all overnight stays in the 46,400 apartments that are permanently rented to tourists. However, there are more Airbnb advertisements listed in Paris alone than in the whole of Germany. In Germany there are around 40,000 in total. This development also prompted many established companies to offer sharing economy services themselves.

However, the numbers for Germany are increasing. The number of Airbnb listings in Germany increased by 49% between September 2013 and 2014. The number of guests who stay overnight with Airbnb in Germany has increased by 124% and 133% more Germans have stayed with Airbnb abroad.

The ride-sharing platform BlaBlaCar is active in 22 countries, has around 65 million registered users worldwide and arranges 20 million travelers per quarter (as of 2019). The BlaBlaCar app ( iOS and Android ) was downloaded more than 15 million times.

However, other trends can also be observed. There was a shift from the originally very popular auctions to fixed prices on Ebay, the company is listed on the stock exchange and offers one of the largest online marketplaces. On the other hand, many sharing economy models fail to establish themselves on the market. Examples are the rental apps Whyownit and SnapGoods. It is also noteworthy that only 44% of consumers in the USA are familiar with the offers of the sharing economy and only 19% have ever actively used one offer. This is why people often speak of unjustified ( media ) hype or a sharing economy bubble .

Controversy and criticism

The sharing economy is a controversial topic that has been criticized on several levels. An important point is that there are different views or variants of a "sharing economy" and that some business models or concepts are often incorrectly assigned. The central criticism that is often cited is that sharing economy providers can offer their products and services without any regulatory requirements and controls and thus have an unjustified advantage over traditional, regulated offers (e.g. hotels, taxis, restaurants). However, the increasing professionalization raises the question of whether the occasional and z. Partly remunerated parts of one's own apartment or other resources should be seen as commercial competition to local hotels or rather as a private business. For example, although Airbnb emphasizes that most providers only advertise one apartment, around 40 percent of sales in Berlin come from offers from providers with more than one advertisement. It can therefore be assumed that in many cases there is a commercial activity. As a catchphrase for this criticism, based on “ greenwashing ”, so-called “sharewashing” is increasingly being used, which describes the abuse of “sharing” for the economic benefit of individual actors.

On the other hand, sharing may result in a legal need for change: At Airbnb, these changes affect, for example, tenancy law, the registration law, insurance law, trade regulations or security standards.

Beyond the regulatory aspects, it is criticized that the sharing economy, contrary to the actual objective, often leads to unsustainable solutions. It is reported that concepts like Airbnb's are exacerbating the emergency on the housing market in urban areas, as apartments are being offered to tourists. In rural areas, however, rentals through Airbnb should make a positive contribution to maintaining rural structures by drawing additional guests' attention to the region. The potential negative influences on the environment are also discussed. For the New York taxi market, for example, it was determined that the number of registered taxi rides has risen sharply since Uber entered the market, resulting in increased CO 2 emissions.

It is also pointed out that platforms of the sharing economy pose a significant risk potential for privacy, as the data available there (especially on the provider side) can be very informative with regard to personal aspects (whereabouts, preferences, interests, etc.). This includes data provided by the users themselves (e.g. name, place of residence, profile pictures, interior photos of the apartment on Airbnb, travel plans on BlaBlaCar), as well as information generated by third parties (e.g. mutual review texts).

Another issue is discrimination, e.g. B. based on skin color or origin. Studies on Airbnb show that white apartment providers can get 12% higher prices than African-American providers. Queries from users with typically Afro-American names are also accepted 16% less often than identical queries from users with typically Caucasian names.

It is also criticized that the sharing economy used to transform things that were offered free of charge, rather out of friendship or based on social norms, into marketable goods and thus - contrary to its otherwise alleged objective - ensures an increasing commercialization of many areas of life. The criticism is also directed at the fact that the sharing economy - like other Internet-based business models - is subject to the laws of the free market. The sociologist Harald Welzer calls it "platform capitalism". The tendency for large providers to prevail while small providers do not achieve critical mass and are pushed out of the market can also be observed in this case. The possible cause for this are network effects that lead to so-called winner-takes-all markets for platforms.

Some researchers see a connection with the change in public institutions and criticize the optimistic expectations, according to the London-based consumer historian Frank Trentmann :

“Modern societies have long had forms of sharing. Libraries , municipal swimming pools , trams - these are just not perceived as sharing. Many visionary texts proclaim a golden age of sharing, but I go down the street in London and the local library is closed. Due to the squeezing of public funds , there is less sharing. "

The Berlin cultural scientist Byung-Chul Han criticizes the terms “sharing economy” and the idea of community. These are only a pretext for “ techno-capitalism ”.

Tax problems

It is further argued that providers of private services and products are taxable, even if rentals are only occasional. So the rental z. B. via Airbnb generally lead to taxable income according to the Income Tax Act (EStG). As a rule, income is not declared and taxed. With regard to taxes and duties, it is criticized that the respective authorities are unable to carry out their control activities to the full extent due to data protection barriers. The politicians therefore demand a proper taxation of the income. In the Netherlands, for example, Airbnb pays a tax directly.

Labor law problems

In addition, platform operators such as Uber are accused of earning from agency fees (20%) and thus unduly enriching themselves from the services provided by others, but at the same time rejecting any responsibility for their drivers with the argument that they are only acting as an intermediary. Important aspects in this context are protection against dismissal, minimum wages, occupational health and safety and working time rules. Providers such as Uber or Helpling are accused of promoting the emergence of new forms of self-employment, which DGB boss Reiner Hoffmann called “modern slavery”. A survey by the McKinsey Global Institute of 8,000 participants from the USA, Great Britain, Germany, Sweden, France and Spain found that 30% of those surveyed are self-employed that they had not chosen voluntarily.

Regulation of the sharing economy

Various groups and interest groups are calling for greater regulation of the sharing economy by national legislators and the European Union. Numerous points of criticism such as the complete abolition of employee protection, lack of insurance and liability regulation as well as distortion of competition and tax loopholes are given as reasons for enforcing the regulation or even a ban on such offers.

In March 2015, for example, the Frankfurt Regional Court banned UberPop from operating in Germany. The private drivers lack the license necessary for commercial passenger transport. Uber incites drivers to break the law by allowing private individuals to offer driving without the need for a taxi or chauffeur license. The German taxi industry had sued in Frankfurt. In other countries such as Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Thailand and France, Uber has been completely or partially banned.

Accommodation providers such as Airbnb, Wimdu and 9Flats are in conflict with the authorities in Berlin, for example. In June 2016, for example, the Berlin Administrative Court prohibited the rental of normal apartments to tourists. Some landlords and the Wimdu platform failed with their lawsuits against the judgment.

New York City passed a law in 2010 that banned the rental of apartments for less than 30 days. A specification of the facts (advertising is already forbidden) and a tightening of the penalties to up to US $ 7,500 per violation should improve the so far moderate enforcement success. For the largest local provider - Airbnb - New York City is one of the most important markets in the USA with more than 40,000 advertisements. However, the passage of the law has been delayed several times due to appeals and lawsuits. New information on the procedure is expected on November 18, 2016.

Due to the different legal situation in different countries or cities, many consumers are not clear about which service is allowed or prohibited in which form. The European Union would therefore like to provide clarity with new, uniform guidelines and contribute to a balanced development of the economy. The European Sharing Economy Coalition (EURO-SHE), founded in September 2013, is committed to giving the sharing economy a unified voice. In June 2016, the EU Commission warned national governments against blanket bans on sharing offers.

Individual focuses

With the term car sharing , a business model has been established internationally. The global market for car sharing amounts to one billion euros. A study from 2013 expected growth to ten billion euros by 2016. In 2012, Stiftung Warentest came up with a model calculation with 5,000 annual kilometers at a cost of 138 euros per month, with its own car, however, 206 euros per month.

Under the term foodsharing , a social movement has emerged that is dedicated to the distribution of surplus food . There are various methods of doing this: some organizations distribute food that is no longer used to those in need before the best-before date has expired , others also use food after the best-before date has expired. The focus of the aid organization Tafel , which is organized in local associations in Germany, is on documented determination of need. Since the food associations mostly only cooperate structurally with sufficiently large companies such as supermarkets, numerous smaller groups and organizations have also formed, in Berlin alone more than 25 different projects.

As a nationwide association called Bündnis Lebensmittelrettung, an attempt is made to persuade the federal government to create a legal regulation based on the French model, which obliges supermarkets above a certain size to pass on all food that is still safe to use.

While food thrown away from waste containers is taken away with so-called “ containers ” , the concept of “food sharing” should start beforehand and the food should be passed on for further use instead of being disposed of. The association Foodsharing.de has since 2012 in the Internet a platform for Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Hawlitschek, F., Teubner, T., Gimpel, H. (2018). Consumer motives for peer-to-peer sharing . Journal of Cleaner Production 204, pp. 144-157

- ↑ a b Manuel Trenz, Alexander Frey, Daniel Veit: Disentangling the facets of sharing . In: Internet Research . August 6, 2018, ISSN 1066-2243 , doi : 10.1108 / IntR-11-2017-0441 ( emerald.com [accessed August 16, 2019]).

- ↑ Frey, A., Trenz, M., and Veit, D. 2019. “A Service-Dominant Logic Perspective on the Roles of Technology in Service Innovation: Uncovering Four Archetypes in the Sharing Economy,” Journal of Business Economics (89: 8-9), pp. 1149-1189. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-019-00948-z).

- ↑ a b Puschmann, T., Alt, R. (2016). Sharing economy . In: Business & Information Systems Engineering, Vol. 58 (2016). Pp. 93-99.

- ↑ CeBIT 2013: The main theme is "Shareconomy" . heise online. September 11, 2012.

- ↑ Infographic: The German Shareconomy Landscape .

- ^ The Sharing Economy Lacks A Shared Definition . November 21st 2013.

- ↑ Teubner, T., 2014, Thoughts on the Sharing Economy . Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Commerce. Vol. 11. pp. 322-326.

- ^ Felson, M., Spaeth, JL (1978). Community Structure and Collaborative Consumption: A Routine Activity Approach . In: American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 21, No. 4. pp. 614-624.

- ^ Martin Weitzman: The Share Economy: Conquering Stagflation. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 1984.

- ↑ Lawrence Lessig: Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy . Penguin, 2008, ISBN 978-0-14-311613-4 , pp. 143-154 .

- ↑ Alex Stephany: The Business of Sharing: Making it in the New Sharing Economy . Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, ISBN 978-1-137-37617-6 .

- ↑ Homestayin.com: Homestay is the origin of the sharing economy. March 11, 2014, accessed June 23, 2019 .

- ↑ Botsman, R., Rogers, R. (2010). What's Mine is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption is Changing the Way We Live . Collins London.

- ^ The case for collaborative consumption .

- ↑ The topic of "online ridesharing" in the context of the sharing economy is exemplified in: Maximilian Lukesch: Sharing Economy in Logistics: A theory-based concept for online ridesharing . SpringerGabler, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-27416-0 .

- ↑ Hawlitschek, F., Teubner, T., & Gimpel, H. (2016). Understanding the Sharing Economy — Drivers and Impediments for Participation in Peer-to-Peer Rental . In: Proceedings of the 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), pp. 4782-4791.

- ↑ Hawlitschek, F., Teubner, T., Weinhardt, C. 2016, Trust in the Sharing Economy . The company - Swiss Journal of Business Research and Practice 70 (1), pp. 26–44.

- ↑ Gansky, L. (2010). The Mesh: Why the Future of Business is Sharing . Penguin.

- ↑ Stephany, A. (2015). The Business of Sharing: Making It in the New Sharing Economy . Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online . Journal of Business Research, 67 (8), 1595-1600.

- ↑ Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., and Ukkonen, A. (2016). The Sharing Economy: Why People Participate in Collaborative Consumption . Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 67 (9), 2047-2059.

- ^ Moeller, S., Wittkowski, K. (2010). The Burdens of Ownership: Reasons for Preferring Renting . In: Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, Vol. 20, No. 2. pp. 176-191.

- ↑ https://www.zeit.de/wirtschaft/2016-07/sharing-economy-teile-tauschen-airbnb-uber-trend

- ↑ a b PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (2015). The sharing economy . Consumer Intelligence Series. Paper retrieved from www.pwc.com

- ^ Roland Berger Strategy Consultants GmbH (2014). Shared Mobility: How New Businesses Are Rewriting the Rules of the Private Transportation Game . Think Act. Paper retrieved from www.rolandberger.com/

- ↑ About Us - Airbnb .

- ↑ Ranking of the most valuable digital start-ups worldwide 2016 - statistics .

- ↑ Proserpio, D., Zervas, G. (2016). The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry . Paper retrieved from cs-people.bu.edu ( Memento of the original from November 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Approximately every eleventh city travelers in Germany sleeping Co. to Airbnb & .

- ↑ Airbnb: Housing brokerage is booming .

- ↑ Alexander Frey, Manuel Trenz, Daniel Veit: Three Differentiation Strategies for Competing in the Sharing Economy . In: MIS Quarterly Executive . tape 18 , no. 2 , May 29, 2019, ISSN 1540-1960 , doi : 10.17705 / 2msqe.00013 ( aisnet.org [accessed August 16, 2019]).

- ↑ Airbnb accommodations: Growth in Germany 2015 - Statistics .

- ↑ Maximilian Lukesch: Sharing Economy in Logistics: A theory-based concept for online ridesharing services . SpringerGabler, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-27416-0 , pp. 13-15 u. 20-21 .

- ↑ About us - BlaBlaCar .

- ↑ Kai Biermann: Ebay auctions: Customers don't like buying anything anymore - ZEIT ONLINE . May 29, 2013.

- ↑ Sales Mechanisms in Online Markets: What Happened to Internet Auctions?

- ↑ Start-up Whyownit has failed - WiWo founder . February 25, 2015.

- ^ The "Sharing Economy" Is Dead, And We Killed It . September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Don't buy the 'sharing economy' hype: Airbnb and Uber are facilitating rip-offs . May 27, 2014.

- ↑ Malhotra, A., Van Alstyne, M. (2014). The Dark Side of the Sharing Economy ... and How to Lighten It . In: Communications of the ACM, Vol. 57, No. 11. pp. 24-27.

- ↑ Defining The Sharing Economy: What Is Collaborative Consumption – And What Isn't?

- ^ A b Koen Frenken, Toon Meelen, Martijn Arets, Pieter van de Glind: Smarter regulation for the sharing economy . May 20, 2015.

- ^ Julian Dörr, Nils Goldschmidt: Share Economy: From the value of sharing . 2nd January 2016.

- ↑ a b "Sharing Economy" - the curse and blessing of the sharing economy .

- ↑ Slee, T. (2016). What's Yours is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy. Or Books.

- ↑ Share Washing - P2P Foundation .

- ↑ https://www.zeit.de/wirtschaft/2019-08/wohnungsmarkt-airbnb-berlin-verwaltung-ferienwohnung-illegal- Zweckentfremdung

- ^ The dark side of Uber: why the sharing economy needs tougher rules . 17th April 2016.

- ↑ Frey, A., v. Welck, M., Trenz, M., Veit, D. 2018. “A Stakeholders' Perspective on the Effects of the Sharing Economy in Tourism and Potential Remedies,” in Proceedings of the Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik (MKWI) , Lüneburg, Germany.

- ↑ Share Economy - sharing alone is not enough for the environment

- ↑ Teubner, T., Flath, CM (2019). Privacy in the sharing economy . Journal of the Association for Information Systems 20 (3), pp. 213-242

- ↑ HBS Working Knowledge: Racial Discrimination In The Sharing Economy .

- ^ Edelman, B., Luca, M. (2014). Digital Discrimination: The Case of Airbnb.com . Working paper. Paper retrieved from www.hbs.edu

- ^ Edelman, B., Luca, M., Svirsky, D. (2016). Racial Discrimination in the Sharing Economy: Evidence from a Field Experiment . Forthcoming, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. Paper retrieved from www.benedelman.org

- ↑ Sharing Economy: Curse or Blessing? .

- ↑ Don't believe the hype, the 'sharing economy' masks a failing economy . September 27, 2014.

- ↑ platform economy . In: Mike Weber (Ed.): ÖFIT trend show: Public information technology in the digitized society. Competence Center Public IT, 2017, accessed on July 13, 2017 ( ISBN 978-3-9816025-2-4 ).

- ↑ Jan Pfaff: “Consumption is not just acquisition”. taz , December 14, 2017, accessed December 15, 2017 .

- ↑ https://www.wiwo.de/politik/ausland/tauchsieder-was-kom-nach-dem-liberalismus/25234600.html

- ↑ Maximilian Krämer: Tax law when renting via Airbnb & Co. In: lto.de. lto.de, September 9, 2019, accessed on September 10, 2019 .

- ^ Joachim Jahn, Manfred Schäfers: Online mediation exchanges: The tax authorities are on the trail of Airbnb and Uber . October 30, 2014.

- ↑ Simon Schumich: Sharing Economy, The economy of sharing from the point of view of employees . ÖGB Verlag, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-99046-248-5 .

- ^ A b SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg Germany: Online companies: DGB warns of new models of exploitation .

- ↑ USA-Netherlands-company-hospitality-Internet: Airbnb online portal will soon levy taxes on tourists in Amsterdam - WELT .

- ↑ Sharing Economy: Earning money with money . July 10, 2014.

- ↑ Thorsten Schröder: Taxi Alternative: The Uber Flyer . 12th of February 2014.

- ↑ Julia Wadhawan: "In the end, Uber always wins " . Time online. June 22, 2016.

- ^ Exploding myths about the gig economy. Retrieved September 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Nightmare Share Economy - All content - DW.COM - 08/27/2014 .

- ↑ Dietmar H. Lamparter, Götz Hamann: Uber: Battle for the passenger . September 27, 2014.

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg Germany: Verdict on the driving service: UberPop banned in Germany - that's good .

- ↑ Court bans UberPop in Germany

- ↑ Jon Russell: Uber Suspends Its Uber Pop Ride-Sharing Service In Spain Following A Court Ruling .

- ↑ Ingrid Lunden: More Woe For Uber As Ride Sharing Service UberPop Ban Upheld In The Netherlands [Updated ] .

- ↑ Startup Uber: Private taxi service Uberpop prohibited - Golem.de .

- ↑ Thailand suspends Uber and Grab motorcycle taxi service . 19th May 2016.

- ↑ Natasha Lomas: France Bans UberPop Starting January 1 .

- ↑ AirBnB, Wimdu & Co. - Misappropriation of apartments in Berlin remains prohibited .

- ↑ This website is currently unavailable. . Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg Germany: AirBnB and Co .: Court confirms holiday apartment ban in Berlin .

- ^ Nils Röper: New law: Airbnb in New York before the end . October 27, 2016.

- ↑ Josh Barbanel: The Enforcement of Airbnb Law Postponed Again . 5th November 2016.

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg Germany: New York: Airbnb landlords face trouble with the law .

- ^ LTO: guidelines of the European Commission .

- ↑ Reuters Editorial: EU Commission warns governments about banning Airbnb and Uber .

- ↑ Markus Fasse, Silke Kersting: The new pleasure in the rental car . In: Handelsblatt . July 9, 2013, p. 20 .

- ↑ Stiftung Warentest: Car sharing - for whom car sharing is worthwhile February 14, 2012.

- ↑ Breakfast TV Article about food sharing on Sat.1 Breakfast TV, as of May 21, 2014, accessed on September 11, 2019

- ↑ Anja Nehls: Grocery rescuers in Berlin: Recycling instead of throwing away , deutschlandfunkkultur.de from November 7, 2019, accessed November 8, 2019

- ↑ Web presence of the Alliance for Food Rescue , accessed November 8, 2019

literature

- Don Tapscott, Anthony D. Williams: Wikinomics: The Revolution on the Net. 1st edition. Hanser, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-446-41219-4 .

- Clay Shirky: Here comes everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. 1st edition. Penguin Press, New York 2008, ISBN 978-1-59420-153-0 .

- Kurt Matzler, Viktoria Veider, Wolfgang Kathan: Adapting to the Sharing Economy , MIT Sloan Management Review, 56 (2), 2015, pp. 71–77.

- Daniel Schläppi and Malte-Christian Gruber (eds.): From the commons to the share economy. Common property and collective resources from a historical and legal perspective . Series of contributions to legal, social and cultural criticism, vol. 15. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, ibid. 2018, ISBN 978-3830538332 .

Web links

- Sharing as a billion dollar business - the sharing economy - contribution by Jeanette Seifert with additional material in the Funkkolleg Wirtschaft

- Who shares, loses . A feature about the opportunities and risks of the “sharing economy” - ARD radio feature by Caroline Michel, June 24, 2015

- Swap instead of buy - how does technology change consumption? - future.arte.tv