Siegburg stoneware

Siegburg stoneware is a type of ceramic product that was produced in the Rhineland pottery town of Siegburg- Aulgasse in the late Middle Ages and early modern times . The Siegburg pottery was traded in large quantities throughout Europe in the 14th to 17th centuries and, in addition to its importance in art history, is an important marker for dating archaeological sites from this time. It is one of the dominant types of goods among German stoneware .

Historical development

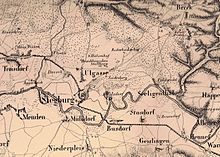

The establishment of a pottery site in Siegburg-Aulgasse in the late Middle Ages was favored by the existence of high-quality clay deposits and rich forests for firewood near the city.

Another favorable factor was the location's proximity to the Sieg . The river was navigable between Siegburg and its confluence with the Rhine until modern times , so that the pottery site was connected to the trade routes of the Rhine and Maas .

Despite innovative shapes, such as the funnel neck beaker typical of Siegburg stoneware , which was developed here in the 14th century, Siegburg pottery products lagged behind Cologne stoneware for a long time . Only when the Cologne potters were driven out of the city in the middle of the 16th century did the Siegburg location reach its heyday. The Anno Knütgen workshop plays a particularly important role . It is possible that former Cologne workmen, such as Franz Trac , found new jobs in Siegburg at that time and brought with them the knowledge of new techniques of the Cologne master potters. With the Truchsessian War , in which the city of Siegburg was involved, stoneware production in Aulgasse experienced its first slump. In 1586/87 Spanish troops under the command of Don Fabion Gonzago besieged the city. Since the Aulgasse pottery settlement was right in front of the protective city wall, the soldiers took quarters here during the siege. When they retreated, the Spaniards set the houses on Aulgasse on fire.

Another siege of Siegburg was less severe for the people of Ulm in 1615, when Brandenburg troops tried to take the city in the course of the Jülich-Klevian succession dispute. The belongings of the pottery families in the Aulgasse were largely spared.

During the Thirty Years War , the distance selling of Siegburg stoneware initially declined. In the Aulgasse, however, stoneware production continued at a high level of craftsmanship until the town was sacked and destroyed by Swedish troops under General Baudissin in 1632 . The houses and workshops in Aulgasse were also burned down. The Swedes held Siegburg for three years. During this time the left-wing citizens became impoverished and stoneware production almost came to a standstill.

In addition to the consequences of the war, there were legal reprisals at the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century. The rich pottery families saw themselves increasingly exposed to the witch hunt of their family members and gradually left the city to settle in Troisdorf-Altenrath and in the Kannenbäckerland . Here they started again an important stoneware production. Only three master potters remained in Aulgasse in the middle of the 17th century, but they hardly produced any significant quantities of stoneware. From the 17th century, the importance of Siegburg production fell far behind that of the Westerwald ceramics .

Ulner and Ulner guild

The Siegburg potters called themselves "Ulner" or "Eulner". These expressions are derived from the Latin "olla" = pot. The potters' settlement northeast of the gates of Siegburg was named after the residents Ulgasse or Aulgasse, which is also the current place name.

Before 1429, the Siegburg potters formed a guild under the control of the Siegburg abbot. The guild regulations were rewritten in 1516, 1532, 1552 and 1706 and were followed into the 18th century. This still-preserved guild order regulated the manufacture and trade of Siegburg stoneware in 42 articles. In the closed guild, the knowledge of the Siegburg potters was only allowed to be passed on to sons born in wedlock. The apprenticeship lasted six years. If a potter died without a successor, his widow was allowed to continue the business.

A master potter was given the number of ovens he was allowed to drive in a year. Normally there were nine to sixteen ovens that could be filled between Ash Wednesday and St. Martin's Day . During the frosty period in winter, the production of stoneware was prohibited for quality reasons. Stoneware orders from the Cologne gentlemen, which could also be served in the winter months, were an exception. Four selected masters (kerbmasters), two of whom were newly elected every year, monitored compliance with the guild rules. They set production quantities and prices and represented the Ulner guild in all matters to the outside world. Their judgments could only be appealed to the abbot.

In addition to the master potter and his family, a guild company owned by an Ulner also included workmen, dependent potters with completed apprenticeships. Numerous craftsmen were also employed. So-called Dagräber (Tongäber, Da = clay), who mined clay in the open-cast mine and Damächer who prepared the raw clay for pottery, oathsmen , assistants in the workshops who had to swear not to disclose the company secrets of their employer, and Holzer who did what was necessary Firewood was cut and workers were provided for ancillary activities such as building the stoves, transport work, etc. No worker was allowed to leave his company during the production period. Was a worker in the following year for another Ulnermeister work, he had to go to St. John's notice.

The strict order of the blocked Ulner guild meant that Siegburg's stoneware production was in the hands of a few families for centuries. The most important pottery families were the Knütgen , Vlach (Flach), Omian and Simons (Zeiman) families.

After the emigration of the master potters at the beginning of the 17th century, only three master potters remained in Siegburg from these families. In order to prevent the threat of extinction of the Ulner guild, Abbot Johann von Bock zu Pattern took Eberhard Lutz from Koblenz-Ehrenbreitstein into the guild for the first time in 1654 .

regional customs

In Siegburg it was a cultivated custom to let the poor share in the prosperity of the people of Ulner. On the day before the feast of St. Anno (December 5), every resident in need of help in Aulgasse was allowed to pick up a mug from one of the local Ulner residents. The needy in the monastery got this filled with beer (Annonis beer). The custom stipulated that the jug was only filled as far as the recipient could still lift with one hand. The needy person received a white pfennig and a pound of barley for the beer donation .

trade

Siegburger Steinzeug was very popular all over Europe due to its quality and craftsmanship. Trade in the large Hanseatic cities and the North Sea area was mostly done by Cologne merchants. In this way, Siegburg stoneware products became known abroad as "Cologne stoneware". In Cologne itself, stoneware production (jug bakery) was banned by a council decision after 1542, but Cologne traders were among the largest buyers of Siegburg Ulner. At the same time, Siegburg merchants in Cologne enjoyed a great reputation and the privilege of being exempt from customs duties. They were allowed to stay in the city of Cologne for up to two years without having to join one of the gaffs , as is usually the case .

The Siegburg master potters usually concluded long-term contracts with a fixed minimum sales and an exclusive clause with a dealer who was supposed to supply a certain area. With regard to the allocated quantities, the Cologne merchants were clearly preferred. But the wine regions of southern Germany were also a priority sales area.

Raw clay export

Despite the excellent quality of the Siegburger clay, which is well suited for filigree ceramic products, clay pipes or pipe figures were never made in Siegburg. However, the raw pipe clay from the Siegburg clay pits was exported. In the 17th to 19th centuries, clay pipes made of Siegburg clay were made in Cologne, on the Lower Rhine and in the Netherlands. For example, in 1687 the pipe bakers from Gouda , Wesel and Duisburg secured Siegburger clay from the dealer Christoffel Horningh.

technology

The Siegburg in the so-called Dakaule pending tertiary refractory clay is of a uniform fine grain size and low in iron oxide. The lack of iron means that the Siegburg clay burns to a light, almost white body. It has been dismantled since Roman times and used for the production of earthenware . The clay for the stoneware production was primarily obtained between Siegburg and Lohmar in the Klinkenberg brands and in the Lohmar forest.

The stoneware production begins in Siegburg around 1400. The first vessel types already show the light shards typical of Siegburg. They are flamed red and have a wave base. The first, small circular editions appear as decor.

During the 15th and early 16th centuries, Siegburg mainly copied models from Cologne, despite some of its own developments. From the middle of the 16th century onwards, artistically pronounced, large circular editions with allegorical-religious and ornamental motifs appeared in Siegburg. Probably under the influence of Cologne derived work of the men are in Siegburg pottery elements High Renaissance introduced into the hitherto still Gothic embossed type spectrum. From 1559 the designs by Franz Trac in the workshop of Anno Knütgen seem to have been decisive.

The technique of salt glaze , which is common in other Rhenish pottery locations , was only rarely used in Siegburger Steinzeug. The shine of the stoneware vessels was achieved by a flash of ash during the firing process. In the second half of the 16th century, the Anno Knütgen workshop experimented with a blue salt glaze, but was unable to achieve the desired success in Siegburg. Only after his migration to Troisdorf-Altenrath did Knütgen establish this technique in the Kannenbäckerland, where he created the blue-gray stoneware typical of the Westerwald.

Form spectrum

The range of shapes of the stoneware produced in Siegburg consists primarily of functional ceramics such as jugs, jugs, canteens and drinking utensils. Siegburger stoneware was rather unsuitable for use as cookware, as it can burst with high temperature fluctuations. The décor and design of the goods reached their artisanal climax in the second half of the 16th century.

The Ulner guild regulations stipulated in detail which types of vessels were allowed to be produced and finally also regulated the price at which they had to be sold. The guild letter of 1552, for example, lists 32 different types of vessels.

Funnel neck mug and jug

Siegburg stoneware gained its first supraregional importance from the second half of the 14th century, when the funnel neck beaker was developed here . The first cups of this late Gothic type had a red-flamed surface and were equipped with wave feet. From the 15th century the flamed surface changes to a pure white-gray. The wave base of this drinking cup, which is characteristic of Siegburg, was retained until the beginning of the 16th century and was then replaced by a baroque twisted base with a profile. However, some Siegburg pottery workshops continue to use the wave base with the later forms of the funnel neck cups.

Siegburger speed

One of the best-known types of vessels of the High Renaissance is the fast one . Schnellen are slim, cylindrical jugs that tapers slightly towards the top. They are designed as drinking vessels and have a handle. The floor consists of an often triple profiled plate.

The modern cultural studies today have a slightly different understanding of the term speed than the contemporary use of the term. The vessel type, which is known as fast according to today's conception, was first developed in Cologne before the middle of the 16th century and soon afterwards was adopted by other Rhenish pottery centers, including Siegburg. These richly decorated jugs were intended for an upscale, aristocratic or upper-class group of buyers.

However, the use of the term speedy is proven from traditional Siegburg guild documents as early as the first half of the 16th century. Here, however, the term was used for mass-produced, simple jugs without decoration.

The Siegburger Schnelle achieved art-historical importance in today's sense precisely because of its high-quality decorative editions. The steep wall was initially divided into three image fields, mostly depicting religious or mythological scenes. Likewise popular motifs were allegorical depictions of Christian virtues and cardinal virtues. In addition, coats of arms or floral motifs are known. From the 1560s onwards, Franz Trac was the first to manufacture Patrizen in the workshop of Anno Knütgen, which, based on the Cologne model, combined the entire wall surface into a single image field.

The patrixes made in Siegburg were based on artistic models of their time. Allusions to the copperplate engravings by Virgil Solis and Heinrich Aldegrevers can often be found. Likewise also provided Jost Amman , Hans Sebald Beham , Jörg Breu , Peter Flötner and Anton Woensam suggestions for Siegburger trimmer. Combinations of several motifs from different works of art are also known. For use on the cylindrical outer surface of the rapid, however, the templates could not be adopted one-to-one, but had to be adjusted in perspective, which requires an artistic understanding of the form cutter.

Many Siegburger Schnellen are signed, whereby a simple monogram was usually used as the signature. The signature is always to be found on the decoration, never on the vessel itself. In research, these monograms have mostly been assigned to workmen and master potters since Otto von Falke's investigations . The monograms FT (Franz Trac), LW (unknown), CM (unknown), HH ( Hans Hilgers ), PK (Peter Knütgen) and CK ( Christian Knütgen ) occur most frequently .

Siegburger Pulle

The Siegburger Pullen are very bulbous jugs with a bottle-like, narrow neck and a high lip. The transition from the neck to the shoulder is usually defined by a single circumferential rotating groove. A ribbon handle is attached to the shoulder and neck. The floor consists of a simple flattened stand without a foot. Pulls are decorated on the stomach and shoulders with similar round supports as the funnel cups.

This type of vessel is widespread towards the end of the heyday of Siegburg stoneware production in the second half of the 16th century. After the decline of the Siegburger Ulner, the shape of the Pulle was handed down in the Kannenbäckerland until the end of the 17th century.

Council jug

The term Ratskanne is used to describe a special shape of a can that was obtained in large numbers from the city council of Cologne from the Siegburger Ulners at the end of the 14th century and at the beginning of the 16th century . The shape is still in the late Gothic tradition. The actual oval body of the vessel is tapered at the base to a cylindrical stem that rests on a broad wave base. The neck is usually short and narrow, similar to a pulp. A ribbon handle is attached to the shoulder and neck.

Siegburger Bartmann mug

In the second half of the 16th century, Bartmann mugs also added to the range of shapes in Siegburg stoneware production. Pear-shaped drinking and serving mugs are referred to as Bartmann, which wear a single bearded male face mask on the neck and shoulder of the vessel. This type of vessel based on the Cologne model can be found in almost all Rhenish pottery centers in the 16th century. In the 17th and 18th centuries, they are the most prominent type in Frechen's stoneware range. Bearded men appeared in Siegburg around 1550/1560, but disappeared again from the inventory at the beginning of the 17th century.

In contrast to the Cologne models, stylized but naturalistic male faces with full beards are usually shown on the Siegburg mask pads. Grimace masks, like those used by some Cologne beard men, can only be found sporadically in Siegburg among the very early vessels. The well-known Bartmann mugs are usually between 16 cm and 26 cm high. In addition to the mask, Siegburg Bartmann mugs are often decorated with two friezes over the shoulder of the vessel. In addition, there are floral decorative elements such as arkanthus tendrils or rosette patterns . Opposite the mask pad is a ribbon handle that starts at the neck and ends in a rectangular smear on the shoulder. Occasionally, the decorative overlay, including the beard mask, is colored cobalt blue. Individual Bartmann mugs can be covered with a pattern of blue dots. Cobalt blue colors suggest that the vessels in question came from the workshop of Anno Knütgen, who experimented with cobalt blue in Siegburg. After his migration to Kannenbäckerland, Knütgen did not produce any more Bartmann mugs according to the current state of knowledge.

A typological development of the Siegburg beard men can be seen from the scientific evaluation of the finds presented so far.

The bottom of early Bartmann mugs consists of a simple base plate. After 1570, the soil is profiled higher and stronger. The later Bartmann mugs are also more bulbous as a whole.

With later types of jugs, it was common to mount a tin lid.

A special form of the Siegburger beard men are mugs of the same shape that have a single coat of arms instead of a beard mask. In addition to the coat of arms, these coat of arms mugs can be more richly decorated than ordinary Bartmann mugs. The handcrafted heraldic jugs also come from the workshop of Anno Knütgen. In contrast to the simple Bartmann mugs, potter's signatures are known for the coat of arms mugs. These also refer to the workshops of the Knütgen family. The signatures obtained are HH (Hans Hilgers) and CK (Christian Knütgen).

Jakobakanne

Jacoba jugs are an early Siegburg vessel shape. The tall, slender jugs have a slightly oval body that tapers towards the base. The foot is designed as a wide wave foot. The high, conical neck is set off from the shoulder by a circumferential rotating groove. It opens into a wide, often slightly curved lip. A short ribbon handle is attached to the neck. Jakobak jugs were produced in Siegburg from the end of the 14th century to the end of the 15th century.

The Jacoba jugs probably received their common name today in Holland in the 17th century. Vessels of this type were exported here in large numbers at the end of the Middle Ages. After the Dutch found shards frequently, the assumption spread among them that this jug shape goes back to Jacoba von Bayern . According to legend, the Countess of Holland and Brabant spent her retirement at Teylingen Castle hunting songbirds. After the hunt, she is said to have drank beer from such mugs and then threw them out of the window into the moat.

Siegburger jug

Bar cans are spout cans in which the pouring spout is connected to the neck of the vessel by a web. These jugs, which are already in the Baroque style, have an egg-shaped body that rests on a strongly profiled base. A wide curved strap handle attaches to the neck and shoulder. The neck and belly are decorated with a surrounding picture frieze. The eponymous spout bridge is curved in an S-shape in Siegburg.

Research and museums

Siegburg stoneware is the subject of numerous archaeological and art history publications. A final template, especially the ceramics from the 17th century, is still pending.

As early as 1873, the Catholic clergyman Johann Baptist Dornbusch, chaplain to St. Ursula in Cologne, published a fundamental chronicle on the history and development of Siegburg stoneware.

In 1975, Bernhard Beckmann proposed a first typological classification of the goods on the basis of studies carried out from 1961 to 1966 on a cullet store in Siegburg. He divided Siegburg ceramics from the 12th to 15th centuries into four periods. Beckmann disregarded later goods.

In 1987 Elsa Hähnel published the first part of a two-volume catalog on the Siegburg stoneware inventory from the LVR open-air museum in Kommern . In it, Hähnel takes a critical look at Beckmann's proposals and presents the results of various scientific studies. The second volume was published in 1992.

In 1989/90 the LVR Office for Ground Monument Preservation in the Rhineland under the direction of Thomas Ruppel carried out extensive archaeological investigations in Siegburger Aulgasse number 8. Ruppel excavated a pottery workshop of the Knütgen family, which was probably destroyed in the Truchsessian War on April 11, 1588. Apart from individual essays, a final submission of the excavation results and a full evaluation of the finds are still pending.

Laurenz Heinrich Hetjens compiled the first significant private collection of Siegburg stoneware in the late 19th century. It formed the basis for the German Ceramics Museum and is now open to the public in Düsseldorf. The Museum of Applied Arts Cologne also maintains another extensive collection . In addition, individual pieces of Siegburg ceramics can be found in museums and collections around the world.

Remarks

- ↑ Bock 1986, p. 51.

- ↑ Ursula Francke : Kannenbäcker in Altenrath. Early modern stoneware production in Troisdorf-Altenrath. Rheinlandia, Siegburg 1999, p. 38f.

- ↑ Other derivatives of this expression are known in documents. Until 1530: Ulner or Uyner; up to 1600: Oilner, Oelner, Oulner, Eulner, Euler, Aueler or Aulner; after 1600 mainly Eulner and Aulner occur.

- ↑ Dornbusch 1873, p. 14.

- ↑ Dornbusch 1873, p. 48.

- ↑ Dornbusch 1873, p. 29.

- ↑ Dornbusch 1873, p. 28f.

- ↑ Martin Kügler: clay pipes . Hanusch & Ecker Verlag, Höhr-Grenzhausen 1987, p. 114.

- ↑ Bock 1986, p. 51f.

- ↑ Dornbusch 1873, p. 21.

- ↑ Dornbusch 1873, p. 21f.

- ↑ To this: Heidi Gansohr: Die Siegburger Schnelle. In: Hähnel 1992, Volume 1, pp. 53-62.

- ↑ Barbara Lipperheide: The Rhenish stoneware and the graphics of the Renaissance. Berlin 1961, p. 25ff.

- ^ Falcon 1908.

- ↑ The assignment of the monograms to workmen and master potters is often doubted in the specialist literature. Instead, it is proposed to assign the monograms to specialized mold cutters, who have been proven for other pottery centers, but not yet for Siegburg.

- ↑ Gisela von Bock: The development of the beard mask on Rhenish stoneware. In: KERAMOS. Journal of the Society of Ceramic Friends V., Düsseldorf. Issue 34, October 1966, pp. 30-43.

- ↑ Hahnel 1992, Volume 2, p. 89.

- ↑ Elsa Hähnel, Joseph Halm: Siegburger Bartmann jugs. In: Hähnel 1992, Volume 2, pp. 66-132.

- ↑ Dornbusch 1873.

- ↑ Beckmann 1975.

- ↑ Hahnel 1987.

- ↑ Thomas Ruppel: Siegburg, Aulgasse No. 8 - An overview of the excavation results. In: Korte-Böger 1991, p. 15ff.

literature

- Bernhard Beckmann: The shard hill in the Siegburger Aulgasse. Rheinland Verlag, Bonn 1975.

- Johann Baptist Dornbusch: The art guild of potters in the abteilichen city of Siegburg and their products. With consideration of other important Rhenish pottery branches, especially Raeren, Titfeld, Neudorf, Merols, Frechen, Höhr and Grenzhausen. A contribution to the history of handicrafts on the Lower Rhine. Heberle, Cologne 1873.

- David RM Gaimster: German Stoneware, 1200-1900: Archeology and Cultural History. British Museum Press, London 1997, p. 163ff.

- Elsa Hähnel: Siegburg stoneware. Inventory catalog in 2 volumes, guides and publications from the Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum and Landesmuseum für Volkskunde in Kommern, No. 31. Cologne 1987 (Volume 1).

- Elsa Hähnel: Siegburg stoneware. Inventory catalog in 2 volumes, guides and publications from the Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum and Landesmuseum für Volkskunde in Kommern, No. 37. Cologne 1992 (Volume 2).

- Wolfgang Herborn: The economic and social importance and the political position of the Siegburger potters. In: Bärbel Kerkhoff-Hader: Pottery. (= Rheinisches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 24), Bonn 1982, ISBN 3-427-88251-9 , pp. 127–162.

- Hans L. Janssen: The dating and typology of the earliest Siegburg Stoneware in the Netherlands. In: David RM Gaimster, Marc Redknap, H.-H. Wegner (ed.): On ceramics of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern era in the Rhineland. BAR International Series 440, Oxford 1988, pp. 311-333.

- Otto von Falke: The Rhenish stoneware. 2 volumes. Berlin 1908. (Reprinted in Osnabrück 1977)

- Ursula Francke : Kannenbaker in Altenrath. Early modern stoneware production in Troisdorf-Altenrath. Rheinlandia, Siegburg 1999.

- Ekkart blade: Siegburg stoneware. Catalogs of the Hetjensmuseum Düsseldorf. Düsseldorf 1972.

- Karl Koetschau : Rhenish stoneware. Munich 1924.

- Andrea Korte-Böger, Gisela Hellenkemper Salies: A Siegburg pottery workshop of the Knütgen family. New archaeological and historical research on the Lower Aulgasse. Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1991.

- Andrea Korte-Böger: The Siegburg potters. Siegburger Blätter No. 12, January 2007. digitized PDF (413 kB)

- Gisela Reineking von Bock: stoneware. Decorative Arts Museum of the City of Cologne. Cologne 1986.

- Marion Roehmer : Siegburger Steinzeug. The Schulte Collection in Meschede. Preservation of monuments and research in Westphalia, Volume 46, Zabern Verlag, Mainz 2007, ISBN 978-3-8053-3453-2 .

- Marion Roehmer, Sally Schöne (ed.): Cosmos of forms Siegburger Steinzeug. The collection in the Hetjens Museum. Nünnerich-Asmus-Verlag, Mainz 2014, ISBN 978-3-943904-69-7 .

- Johann Schmitz: The end of the Siegburg pottery guild in Altenrath. In: Heimatblätter des Siegkreises 1 (1925), Issue 1, pp. 14-16.