Steinvikholmen

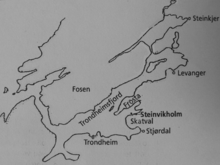

Steinvikholmen is a late medieval island and archiepiscopal church castle with a fortress or fort-like appearance on the island of the same name in the municipality of Stjørdal in Åsenfjord , a north-eastern branch of the Trondheimsfjord in Norway .

start of building

The construction of the fortress was started by the last Archbishop of Norway, Olav Engelbrektsson of Nidaros, in 1525. The fortress was very modern for the time. It was built of stone walled with mortar .

Choice of location

Much has been speculated about the location of the fortress. It is actually not optimally placed for a defense: deep in a fjord, which limits the escape possibilities, and with regard to the transport connections at the time, rather peripheral. From this point of view, Munkholmen , which is closer to town, would have been a better choice. Sverresborg near Trondheim would also have been better fortified: it is also closer to the city, offers better observation possibilities and is more difficult to access.

Olav Engelbrektson was not very communicative about his legacy either, so that he left historians a lot of leeway for speculation about his motives. In a note dated December 10, 1531, he simply wrote: " The fortress Steinvikholm is to serve the gracious king and his successors in Norway and by his grace and to ward off damage and destruction from Norway. " From this it can be seen that the fortress is an instrument in the The power struggle of that time was. The symbolic character of a practically impregnable fortress was also important.

The political situation

There had always been tensions between the royal power and the Church, which had been the subject of many negotiations. The most significant is the agreement between Magnus lagabøte and Archbishop Jon Raude in Tønsberg in 1277. Archbishop Aslak Bolt succeeded in 1458 in persuading King Christian I to essentially recognize this agreement in his electoral surrender, which has hardly been adopted in the meantime King recognized. In this election surrender it was determined that Norway was an electoral monarchy and was governed by the Imperial Council and by Norwegian officials. The feudal lords and the members of the Imperial Council had to be Norwegians or at least have married into Norwegian families.

In 1483 King John I had to sign a similar election surrender in Halmstad in order to be recognized as King in Norway. But in the following years he tried to strengthen his position, especially so as not to lose Norway to Sweden. He tried to achieve this by appointing archbishops loyal to the king.

As early as 1475 the Archbishop of Nidaros was enfeoffed with Trøndelag, so that a similar development had taken place as with the prince-bishops on the mainland. So it came about that the Danish chancellor and provost in Roskilde , Erik Valkendorf , from a Danish noble family, was appointed archbishop. Apparently Erik Valkendorf did not want this office and was also concerned about the king's policy towards the church. The king had to promise him a lot to get him to take over the office. Christian II did not keep these promises, however, but continued his anti-church policy. Erik Valkendorf, for his part, tried to defend the position of the church. There was a conflict between the two. The interests of the king were represented in Norway by Hans Mule and Jørgen Hanssøn against the church. Gradually, Erik Valkendorf gave the king a right of codecision in the election of the bishops, and Christian II brought the church to its knees. In the end, the situation became untenable for the archbishop. Erik went to the king, who tried to take him prisoner, but failed. Then he went to the Pope to present the matter to him. He died in Rome in 1522.

Christian II continued his policy against the Church and the Norwegian nobility. In the meantime he also had the Swedish nobility against him. Here the battle of the Reich Administrator Sten Sture was directed against the Swedish Archbishop Gustav Trolle and against the king. After his death, the Stockholm bloodbath followed . In the general uprising that followed - also in Denmark - Christian II was deposed and fled to the Netherlands .

Frederick I followed in 1523 and Gustav Vasa became King of Sweden. Gustav Vasa sent troops to Skåne and Norway in January and April . That spring, Olav Engelbrektsson was on his way to Rome to get the pallium. This meant a weakening of the Norwegian government, since he was also head of the Norwegian Imperial Council. On the way to Rome he met Christian II in the Netherlands, who had been deposed in Denmark but was still formally King of Norway, and pledged his allegiance to him. On the way back from Rome he pledged allegiance to Frederick I in Denmark. But there was an interregnum in Norway, as no king had yet been elected for this country. Frederick's proposal to recognize him as king by virtue of inheritance law was rejected. It was not until the Lord's Day on August 5, 1524 that allegiance to Christian II was formally revoked. On August 23, 1524 Friedrich was elected King of Norway. In his election surrender, which was very similar to the Danish one, he had to promise not to accept Lutheran teaching. In these turbulent conflicts between the royal power on the one hand and the church and the nobility on the other, which had forced Erik Valkendorf to travel to Rome, to the Stockholm bloodbath and to the overthrow of Christian II, Olav Engelbrektson was elected archbishop.

The fortress

Steinvikholmen lies in the middle of the most fertile part of the Trondheimfjord, where the bishopric of Nidaros owned the most productive estates. In 1435 he owned around 40% of the land there. The land ownership had decreased by Olav Engelbrektson, but he was still the largest landowner in the area. Steinvikholmen was the only fortified place between Vardø and Bergen in its time .

At that time the high water level was 2 m higher than today. Along with the fortress, a bridge was also built across the sound to the mainland. Over time, this led to the silting up of the sound. The island was also smaller then than it is today. A path led to the bridge with a fortified gate, the first of a total of four gates before you came to the bridge. This access was such that right-handers could only come to the bridge with the so-called "open side", i.e. with the shield on the opposite side, and were thus exposed to arrow fire from the defenders.

There were also two palisades at a distance of 25 m abeam from the bridge. The outer palisade ran parallel to the island's shoreline and was probably on the shoreline at low tide in 1525. The palisades had no function unless they were connected to the gates. On the island there was still a gate at the bridge, the remains of the post in the form of a fort. There was a portcullis in front of the gate. In addition, cannons were set up on both sides, one in the tower and one on the east wing.

The castle was almost square with round cannon towers at the corners. It had external dimensions of 50 x 52.5 m. The outer walls were 4 m thick. The outer wall was also the wall for the main building, so it was not actually a curtain wall. The wall of the largest tower in the southwest was 5 m thick. Two cannon towers stood outside at two corners. The tower in the southwest had a diameter of 20 m, the one in the northwest of 17 m in external dimensions. The northeast tower had a secret exit to a good anchorage in the north. This escape route was hidden from view from the mainland. The main building had at least two floors and a cellar in the northwest. The courtyard was very small and measured only 17x24 m.

meaning

Even at the time of construction, Steinvikholmen was referred to in the archbishop's account books as "Castle" ( Steinvikholm slott ). Bishop Johann von Oslo wrote in a letter dated October 20, 1525 that it would never be regretted that Steinvikholmen had been fortified as quickly as possible, because built in peace it is safer in strife. With this he clearly expressed the military meaning, not for a current but for a presumed impending danger. Olav Engelbrektson also referred to Steinvikholmen as "festivals". Steinvikholmen was later often referred to as the "castle". But this word seems to have been a loan word and to have denoted a fortified place.

Nonetheless, the question remains what Olav Engelbrektson thought when choosing this unfavorable location. After all, such a fortress needed a certain hinterland to supply it. Olav Engelbrektson had several tax-free properties in the area. Steinvikholmen probably belonged to him too, at least to the church. From the year 1531 a letter from King Frederick I has been received, in which he confirms that Olav has tax-free ownership of Steinvikholm, among others. Christian II also confirmed his ownership of the island. A letter from the Archbishop of Uppsala , Gustav Trolle, on December 12, 1531 shows that the fortress was built on the land of the church at the expense of the church and the monastery. The church had built the fortress with royal privileges. The archbishop acted as feudal lord in this context.

The archaeological finds show that the fortress was essentially intended to defend itself using powder weapons. Olav Engelbrektson also started to get a fleet. To do this, he needed a safe haven.

The lack of drinking water can certainly be a given reason for the embarrassing abandonment of the fortress in 1564, because the well was deepened considerably in 1542 and has never dried up again. Nevertheless, the castle was abandoned in 1564 after only six days of siege.

In addition to defense, the castle apparently also served representational purposes. The archbishop received the royal negotiators there and not at the bishopric in Nidaros in 1532 on the question of his allegiance to the king. However, by this time the bishop's court in Nidaros had already burned down. Steinviksholmen was also apparently the safest place to keep treasures, and the archbishop was given such treasures to be kept at Steinvikholmen.

The fortress in operation

- In 1532 the army of the Danish king under Otte Stigsen, Nils Clausen and Tord Roed burned the bishop's court in Trondheim and two estates in Hamre. But Steinvikholmen was not attacked.

- In 1537 the Archbishop manned Steinvikholmen and the monastery on Nidarholmen . After a short time he himself fled to Sweden to Gustav Trolle and from there to the Netherlands, where he died in Lier . Before he fled, he ordered the crew to defend the fortress. Apparently he thought he could return later. Christian III troops besieged the monastery on Nidarholmen from the sea and at the same time Steinvikholmen from the land. After a month there were negotiations and the handover without a fight.

- 1564 During the Northern Seven Years' War , Swedish troops came to Steinvikholmen fortress on February 28, 1564. The fortress was abandoned on March 5th at 11 a.m. The liege of the fortress, Evert Bille, soon realized that he would not be able to withstand the siege in the long term. Therefore, he began early negotiations with the French general of the Danish army, Claudius Carolus in Bergen , knowing full well that he would also have to give up the fortress again as soon as the situation changed. On May 22nd of the same year the fortress, which the Swedes had occupied with 500 men, was recaptured. The attempt to retake it again by the Swedes in the same year failed.

- In 1565 the Swedish army tried a third time to take the fortress, but this also failed. That was the last military attack on the fortress.

The further fate of the fortress

The fortress then fell into disrepair and funds for its restoration have only recently been approved. At the end of the 19th century, the first archaeological excavations took place there on the occasion of the 900th anniversary of the Archdiocese of Nidaros. From today's perspective, the results are insufficiently documented. The information about the stratigraphic allocation of the finds is not sufficient, so that dating based on the layers of the find is not possible and therefore no history of construction and use can be made.

Since 1992, an opera about Archbishop Olav Engelbrektson has been performed almost every year on the open-air stage of the fortress at Steinvikholm Music Theater.

The Steinvikholmen fortress is owned and operated by the "fortidsminneforeningen" (antiquity association) today.

Footnotes

- ↑ a b Diplomatarium Norvegicum VIII No. 659

- ↑ Nordeide p. 8 f.

- ↑ In the Scandinavian languages, as in English, there is usually no distinction between a castle or a palace.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norwegicum Vol. 7 No. 612

- ↑ This is why it is not recorded in Norrøn Ordbok , which only contains words from before 1350.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norvegicum XI No. 571

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norvegicum VIII, No. 660

- ↑ Nordeide p. 30

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norwegicum XII, No. 525.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norvegicum V, No. 1077.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norvegicum XII, No. 576 and 577

- ↑ Nordeide p. 29

- ↑ Nordeide p. 23

literature

- Arne Bergsgård: 1955. "Olav Engelbriktsson,". In: A. Fjellbu (ed.): Nidaroserkebispestol og bispesete 1153-1953, Vol. 1: Nidaroserkebispestol og bispesete 1153-1953, pp. 533-567. Trondheim 1955.

- Halvard Bjørkvik: Folketap og sammenbrudd 1350–1520. In: Aschehougs Norges Historie Bd. 4. Oslo 1996. ISBN 82-03-22017-7

- Grethe Authén Blom: Hellig Olavs by. Middelalder til 1537 . In: Trondheims historie 997–1997. Oslo 1997.

- Diplomatarium Norvegicum

- P. Gravbrøt: Steinvikholm. - "Det lå en borg i Åsenfjord ...". hovedoppgave, University of Trondheim 1993.

- A. Hahr, Två norska renässansborgar, Östraat och Steinvikholm. Nordisk tidsskrift 1919, pp. 272-283.

- D. Johnson: Leonardo da Vinci and Steinvikholm slott. Volund 1957 pp. 117-123.

- G. Kavli: Norges festninger. Fra Fredriksten til Vardøhus. Oslo 1987.

- A. Krefting: Undersøgelser i Steinviksholms ruiner 1886. Foreningen til Norske Fortidsmindesmerkers Bevaring. Aarsberetning for 1886, Kristiania 1887.

- A. Krefting: Beretning om udgravninger paa Stenviksholm 1893. Foreningen til Norske Fortidsminnesmerkers Bevaring Årsberetning. Kristiania 1894 pp. 1-14.

- J. Leirfall: Steinvikholm . Borrowers and builders: Foreningen Steinvikholms venner. 1969.

- Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide: Steinvikholm slott - on transition from the middle to the next time. Temahefte 23, Norsk institutt for kulturminneforskning pp. 1–82. Trondheim 2000. ISBN 82-426-1120-3

- T. Lysaker: Erkebispegården som residences for lords and the første foundation offices. Trondhjemske Samlinger 1989. Trondheim 1990.

- JA Seip (ed.): Olav Engelbriktssons rekneskapsbøker 1532-1538. Oslo 1936.

- FC Skaar: Steinvikholm slott . Hærmuseet Akershus Årbok 1951-52. Oslo 1953, pp. 22-95.

- FB Wallem: Steinvikholm . Trondheim 1917.

Web links

- Steinvikholm slott gives an impression of how the original castle is imagined today. See also p. 13. On p. 7 is a photo of the current condition.

Coordinates: 63 ° 32 ′ 37.6 " N , 10 ° 48 ′ 47.5" E