Constitution of Thailand

Thailand has had a constitution since the end of absolute monarchy in 1932 . It has often been revised or replaced by a new one since then , especially in connection with the numerous military coups in recent Thai history . Twenty constitutions (including provisional constitutional documents) were promulgated from 1932 to April 2017.

Since 1968 the constitutions have designated Thailand in Article 1 as “a single and indivisible kingdom” and in Article 2 its form of government as “democracy with the king as head of state”. The sovereign is the people, not the monarch.

Constitutional history

Before 1932

Until 1932 there was no constitution in the modern sense. The king was seen as "master of the life" of his subjects. However, traditional regulations such as the Thammasat (the Thai version of the Indian Manusmriti ), the three-seal law and the law of civil, military and provincial hierarchies of 1454 ( Sakdina system) defined the roles of political actors. Until the end of the 19th century, Siam (forerunner of today's Thailand) was not really an absolute monarchy , as the power of the king was restricted by traditions, religious law and, in fact, by the prerogatives of other aristocratic actors. For example, the king was not allowed to pass laws, but only to issue temporary regulations.

It was only Rama V. (Chulalongkorn, r. 1868-1910) who disempowered the provincial princes and converted the ministries from traditional, independent domains of power to modern, subordinate departments. On the one hand this served to modernize the administration, but on the other it led to a strengthening of absolutism. The proposal made by eleven princes in 1887 to enact a democratic constitution based on the European model (while maintaining the monarchy) was rejected by the king on the grounds that his subjects were not yet ready to participate in a parliamentary system.

Chulalongkorn's son Vajiravudh (Rama VI., R. 1910-1925) strictly rejected the adoption of a constitution. In 1912, a coup with the aim of establishing a republic failed. Vajiravudh's brother and successor Prajadhipok (Rama VII., R. 1925–1935), who had studied in Great Britain and was considered to be comparatively liberal, intended to enact a constitution, but the “radical” idea could not go against the powerful Enforce princes in the Supreme State Council.

1932

Thailand, which was then still called Siam, received its first, temporary constitutional document on June 27, 1932, three days after the coup d'état by the Khana Ratsadon (“People's Party”), which ended the absolute monarchy in the country and is also known as the “Siamese Revolution” . These interim statutes for the administration of Siam were intended to facilitate the transition from absolute to constitutional monarchy. She had 39 items. The National Assembly was introduced as a central body as a unicameral parliament with extensive powers. Its members were appointed by the “People's Party”, which mainly consisted of middle-class middle-class officers and state officials.

This document was superseded by the first permanent constitution of December 10, 1932. December 10 is a public holiday to this day as Constitution Day. It was drawn up by an editorial committee, which in turn was set up by the “People's Party” and was intended to institutionalize the exercise of power. The Basic Law had 68 articles, including a provision introducing women's suffrage . Only half of the members of the still single camera National Assembly were to be elected, the rest to be appointed. As long as the majority of the population had not even finished primary school, the “People's Party” did not see the Thai people ripe for full democracy. She herself wanted to exercise its sovereignty in a kind of trust for this. Political parties were not allowed (the khana ratsadon did not see itself as a party in the strict sense). Real power remained in the hands of the military and bureaucrats. The text remained in force for fourteen years.

After Major General Plaek Phibunsongkhram (Phibun) took over government in 1938 and especially after his success in the French-Thai War in 1941, it was increasingly eroded. Phibun gradually eliminated not only the opposition, but also former comrades-in-arms from the “People's Party” and ruled by decrees. He presented himself as a defender of constitutionalism and democracy against the monarchists and had the democracy monument built in 1939 . In view of the looming defeat of the Japanese, with whom Phibun had allied itself in World War II, the parliament reconsidered its powers and removed the prime minister in July 1944.

1946

After the end of the war, a new constitution was drawn up with the aim of modernizing the constitutional framework. It came into force on May 9, 1946 without a coup, which is an exception in Thai history and is considered to be one of the most democratic basic laws the country has ever had. The House of Representatives has now been fully elected. A Senate was set up aside, the members of which were elected by the House of Representatives. For the first time, a large number of political parties were able to form, which were largely responsible for forming a government.

After a year and a half, the constitution was overturned by a military coup . The idea of constitutional statehood was permanently damaged in Thailand. 25 years of almost uninterrupted, sometimes more, sometimes less concealed military dictatorship followed. A transitional constitution was signed and put into effect just two days after the coup by Prince Rangsit Prayurasakdi , who as regent represented the young King Bhumibol Adulyadej . Among other things, this reintroduced the Privy Council , which was abolished after the revolution of 1932 .

1949

The 1949 constitution was largely drawn up by conservative and royalist lawyers. It significantly strengthened the role of the king. Since then, he has been able to appoint his privy councilor at will. The President of the Privy Council got the right to countersign all laws . The National Assembly continued to consist of two chambers, but only the House of Representatives was elected, while the 100-member Senate was appointed by the monarch. In addition, the king was given a right of veto, which required a two-thirds majority in parliament to overcome. He was also able to issue decrees with legal force and call a referendum . The rule of succession to the throne was also changed. Unlike since 1932, it was henceforth the right of the Privy Council and no longer of Parliament to determine who the heir to the throne was. The constitution of 1949 also contained a largely liberal section on the civil rights and obligations of Thais. In addition, the government was dependent on the confidence of the House of Representatives, which it could remove with a vote of no confidence. Officials and active members of the military were again excluded from government offices.

The constitution was rejected from the start by influential sections of the elite, including a substantial number of the 1947 coup plotters and Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram . Dissatisfaction with the constitution is believed to be one of the reasons for the three attempts to overthrow in the following two years. While the palace revolt of 1949 and the Manhattan revolt in June 1951 were crushed, the "silent coup" in December 1951 was successful. The most powerful military officers radioed the 1949 Constitution and announced a return to the (slightly amended) 1932 Constitution.

1952

After the constitution of 1952, which was very similar to that of 1932, there was again a unicameral parliament , half elected and half appointed by the people. The appointed MPs were mostly military, they were allowed to take over government offices again. Parties were initially banned, but were re-allowed in 1955. In 1957 elections were held with a variety of parties, but were manipulated in favor of the Seri Manangkhasila party founded by those in power around Phibunsongkhram . After the coup in September 1957 , the constitution initially remained in force and new elections were soon held. However, since these did not bring the result desired by the putschists around Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat , he seized unrestricted power as part of an authoritarian "revolution" in October 1958, suspended the constitution, dissolved parliament and banned all parties.

1959

For the next ten years, Thailand was left without a real constitution. In January 1959, Sarit had the king put a "statute on the administration of the kingdom" (deliberately not called a constitution ) into force. This had only 20 articles, the most important of which was Article 17, which gave the head of government practically unlimited powers and laid the basis for his dictatorial rule. According to this, the Prime Minister could "whenever he deems it appropriate to prevent acts that undermine the security of the kingdom or the throne", enact decrees with the force of law. These were automatically considered lawful, no one could appeal against them, and no institution was allowed to review them. Among other things, Sarit issued a number of death sentences, citing Article 17. The prime minister thus united legislative, executive and judicial powers in his person. This made the Basic Law of 1959 the most repressive in Thai constitutional history. Although a “constituent assembly” was set up in order to get a real constitution again at some point, it remained in fact inactive. Rather, the appointment to this body was an honor by which Sarit secured the loyalty of subordinate military personnel and bureaucrats.

The “statutes” of 1959 remained in force even after Sarit's death; his successor Thanom Kittikachorn also made use of the dictatorial power of Article 17.

1968

After this nine-year “interim” (which was actually more permanent than most “permanent” constitutional documents), a regular constitution came into force again on June 20, 1968. Although this provided for a house of representatives elected by the people with a multi-party system (17 political parties registered), this was accompanied by a senate with far-reaching powers, whose members were selected by the previous military junta. So the previous rulers were able to keep in office. Nothing changed in the actual balance of power.

However, the head of government and Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn repealed the constitution after only three years, referring to the alleged communist threat. The subsequently adopted interim statute of 1972 was just as authoritarian and repressive as the one of 1959. The process of drafting a new permanent constitution was delayed again and again until the popular uprising broke out in October 1973 , which overthrew the military junta.

1997

The 1997 constitution was exceptional because it was drawn up with the intensive participation of the population and civil society. It was therefore referred to as the “people's constitution”, was considered the most democratic in Thai history and one of the most liberal and modern in Asia. The constitution, which came into force on October 11th when King Bhumibol Adulyadej signed it , introduced a number of so-called independent constitutional organizations which, as “guardian institutions”, watch over the political organs and prevent the abuse of power by elected politicians. The most famous and influential of these is the Constitutional Court . It was repealed after the 2006 coup .

2007

The constitution, which came into force in 2007, was again drawn up under the aegis of the military, but was approved by the people in a referendum .

Like its predecessors, the constitution described Thailand's form of government as “democracy with the king as head of state”. State power was exercised by the executive, legislative and judicial branches ( separation of powers ). Its most important organs were the government, the two-chamber national assembly and the courts. The 2007 constitution strengthened the role of the “independent”, not directly elected guardian institutions and that of the half-elected, half-appointed Senate, while the positions of the executive (particularly the head of government) and political parties were weakened. This has been cited as the lesson from the accumulation of power under Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra that sparked the previous political crisis in 2006.

After the May 22, 2014 coup, the constitution was repealed, with the exception of the section on the monarch.

Transitional constitution 2014 and adoption of a new constitution in 2016

King Bhumibol Adulyadej approved an interim constitution drawn up by the junta on July 22nd. The 48-article text contained an amnesty for those involved in the coup and gave the military rulers practically unlimited opportunities to counter a possible threat to national security.

Article 44 stipulated that instructions given by the junta's leadership were automatically given a legal status that could not be challenged.

According to the document, the interim parliament consisted of 220 MPs, all appointed by the military leadership. This parliament should elect a head of government and up to 35 ministers.

Goals for a permanent constitution were also given. So - as in the previous constitutions - a “democratic system with the king as head of state” should be sought.

A first draft for a new permanent constitution, developed after the coup, was rejected by a majority by the National Reform Council in early September 2015. The majority of the military representatives represented on the body voted against the document, which is why observers assumed that this vote was in line with the wishes of the military junta (although the junta had previously expressed a positive opinion on the draft).

Then the constitutional process began again, which set back the promised return to democracy by several months. The second constitutional committee was chaired by Meechai Ruchuphan (one of the few civilians in the "National Council for the Maintenance of Peace"). According to this draft, the elected House of Representatives is assigned a 250-member Senate, whose members are determined by a selection committee, which in turn is determined by the military junta. Six seats are also reserved for the commanders of the three branches of the armed forces, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, the general director of the police and the state secretary in the Ministry of Defense (traditionally also a general). The appointed Senate can overthrow a future elected government through a vote of no confidence. The referendum on the draft constitution was linked to a cumbersome additional question as to whether the elected House of Representatives and the appointed Senate should jointly determine the Prime Minister in the first five years after the next elected parliament met in order to continue the "reforms in accordance with the national strategic plan" . Critics warned that the military government wants to cement its power with the draft.

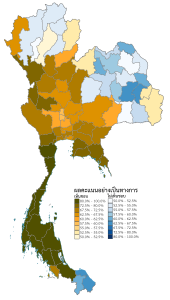

On August 7, 2016, the majority of the Thai population adopted the draft constitution drawn up by the military government in a referendum. Any election campaign before the referendum had been banned beforehand, while criticism of the draft could be punished with up to ten years in prison. With a turnout of around 55%, 61.4% voted for the draft constitution and 58.1% for the supplementary question. However, there was a majority against the text in 23 provinces in north, northeast and extreme southern Thailand.

King Maha Vajiralongkorn initially refused to support the version that was being voted on. Only after various changes - the exact wording not yet known - did he sign the adjusted text on April 6, 2017 in a television broadcast ceremony.

See also

Web links

- Texts of the 2007 , 1997 and 2006 Interim Constitutions online on the Asian Legal Information Institute website.

- Draft Constitution 2016 , unofficial English translation

literature

- Marco Bünte: Constitutional Reforms and Securing Power in Southeast Asia. GIGA Focus No. 1, 2012, ISSN 1862-359X .

- Tom Ginsburg: Constitutional afterlife. The continuing impact of Thailand's postpolitical constitution. In: ICON - International Journal of Constitutional Law , Volume 7, No. 1, January 2009, pp. 83-105, doi : 10.1093 / icon / mon031 .

- Henning Glaser: Setting the course for Thai constitutionalism? - The interim constitution 2014. In: The public administration , No. 2/2015, pp. 60–69.

- Andrew Harding, Peter Leyland: The Constitutional System of Thailand. A contextual analysis. Hart, Oxford 2011, ISBN 9781841139722 . Draft of the 1st chapter by Harding online.

- James Klein: The Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, 1997. A Blueprint for Participatory Democracy. The Asia Foundation Working Paper Series, 1998.

- Eugénie Mérieau: Thailand's Deep State, Royal Power and the Constitutional Court (1997-2015). In: Journal of Contemporary Asia , Volume 46, No. 3, pp. 445-466, doi : 10.1080 / 00472336.2016.1151917

- Pornsakol Panikabutara Coorey: The evolution of the rule of law in Thailand. The Thai constitutions. University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series 2008, Working Paper 45, July 2008.

- Wolfram Schaffar: Constitution in crisis. The 1997 Thai 'Constitution of the People'. Southeast Asian Studies Working Paper No. 23, 2005, ISSN 1437-854X .

- Kobkua Suwannathat-Pian: Kings, Country and Constitutions. Thailand's Political Development, 1932-2000. Routledge Shorton, Oxford / New York 2003, ISBN 0-7007-1473-1 .

- Chaowana Traimas, Jochen Hoerth: Thailand. Another New Constitution as a Way Out of the Vicious Cycle? In: Constitutionalism in Southeast Asia. Volume 2, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore 2008, pp. 301–325.

- Borwornsak Uwanno, Wayne D. Burns: The Thai Constitution of 1997. Sources and Process. In: University of British Columbia Law Review , Volume 32, 1998, pp. 227-247.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Current background - Thailand votes on a new constitution. Federal Agency for Civic Education, August 8, 2016.

- ↑ On this concept, Michael Kelly Connors: Democracy and National Identity in Thailand , 2nd edition, NIAS Press, Copenhagen 2007, Chapter 6, pp. 128 ff .

- ↑ James Ockey: Making Democracy: Leadership, Class, Gender, and Political Participation in Thailand. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 2004, p. 1.

- ↑ Andrew Harding, Peter Leyland: The Constitutional System of Thailand. A contextual analysis. Hart Publishing, Oxford / Portland (OR) 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Harding, Leyland: The Constitutional System of Thailand. 2011, p. 10.

- ↑ Kullada Kesboonchoo Mead: The Rise and Decline of Thai Absolutism. Routledge Shorton, London / New York 2004.

- ^ A b Harding, Leyland: The Constitutional System of Thailand. 2011, p. 10.

- ↑ Kobkua Suwannathat-Pian: Kings, Country and Constitutions. Thailand's Political Development, 1932-2000. Routledge Shorton, London / New York 2003, ISBN 0-7007-1473-1 , p. 23.

- ↑ Kobkua Suwannathat-Pian: Kings, Country and Constitutions. 2003, pp. 79-80.

- ↑ Chaowana, Hoerth: Thailand. 2008, p. 309.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 437

- ↑ a b Chaowana, Hoerth: Thailand. 2008, p. 310.

- ↑ a b Kobkua Suwannathat-Pian: Kings, Country and Constitutions. 2003, p. 51.

- ↑ Thak Chaloemtiarana: Thailand. The Politics of Despotic Paternalism. Cornell Southeast Asia Program, Ithaca (NY) 2007, ISBN 978-0-8772-7742-2 , pp. Xi, 127-128.

- ↑ Tyrell Haberkorn: In Plain Sight. Impunity and Human Rights in Thailand. Pp. 55-57.

- ↑ Tyrell Haberkorn: In Plain Sight. Impunity and Human Rights in Thailand. Pp. 66-70.

- ↑ Parichart Siwaraksa, Chaowana Traimas, Ratha Vayagool: Thai Constitutions in letter. Institute of Public Policy Studies, Bangkok 1997, p. 12.

- ↑ Thak Chaloemtiarana: Thailand. The Politics of Despotic Paternalism. Cornell Southeast Asia Program, Ithaca (NY) 2007, pp. 186-187.

- ↑ Tyrell Haberkorn: In Plain Sight. Impunity and Human Rights in Thailand. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison (WI) / London 2018, ISBN 978-0299314408 , p. 73.

- ^ Schaffar: Constitution in crisis. 2005.

- ↑ Peter Leyland: Thailand's Constitutional Watchdogs. Dobermans, Bloodhounds or Lapdogs? In: Journal of Comparative Law , Vol. 2, No. 2, 2007, pp. 151-177.

- ↑ a b Ginsburg: Constitutional after life. 2009, p. 83 ff.

- ↑ Thailand Law Forum: The Thai Constitution of 1997 Sources and Process (Part 2)

- ^ Tom Ginsburg: The Politics of Courts in Democratization. Four Juctures in Asia. In: Consequential Courts. Judicial Roles in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press, New York 2013, pp. 58-60.

- ^ Ginsburg: Constitutional afterlife. 2009, p. 100.

- ↑ Art. 2, Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand from 2007. ( Online ( Memento of the original from May 15, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. )

- ↑ Art. 3, Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand from 2007. ( Online ( Memento of the original from May 15, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. )

- ↑ Junta secures unlimited power

- ↑ a b c Lots of leeway for the generals

- ^ Mathias Peer: No new constitution for Thailand. In: Handelsblatt (online), September 6, 2015.

- ↑ Thailand's Reform Council rejects the draft constitution. In: Zeit Online , September 6, 2015.

- ↑ Christoph Hein: The generals in Bangkok cement their power. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . August 7, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016 .

- ^ New constitution for Thailand. In: tagesschau.de . August 7, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016 .

- ↑ Nicola Glass: Changes only for the king. In: the daily newspaper . April 6, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017 .