Ešnunna

Ešnunna or Eschnunna (today's Tell Asmar ) was a Sumerian city-state. It was the central city on the lower Diyala in Sumer and had existed as early as the 3rd millennium BC. Trade relations with the then undeveloped Elam area . The Sumerian influence of this city on Elam was relatively significant, since submission to Sumerian rule was also considered there for a time. However, this submission did not occur.

Another name for the city and its surrounding area known from inscriptions is “Land Tupliaš ” or Ašnunnak .

history

The origins of Eschnunnas go back to a non-Sumerian or non-Semitic population. The original name was Ischnun , from which Eschnunna (Sumerian for sanctuary of the prince ) was formed in the Sumerian language . It is interesting that obviously Babylon (originally Babilla , then Bab-ilim , Greek Babylon ) is not of Sumerian or Semitic origin. After all, Eschnunna was also one of the first cities to be established during the III. Ur Dynasty seceded from central government. This is documented by the lack of documents from the Ensi (possibly Ituria ) in Ur (in year 3 of King Ibbi-Sin of Ur, around 2000 BC). Iturias son, Ilschuilija , called himself "Mighty King of the Land Warium" (the Diyala area, which was ruled by Eschnunna). The names of kings seem immensely exaggerated and did not correspond to the actual political conditions of the time. Eschnunna could not succeed Ur.

Babylonian Empire

Eschnunna also existed as an independent state in the old Babylonian period. He gained power over large parts of central Mesopotamia under the government of Naram-Sins . It is possible that the so-called Codex Eschnunna , a collection of price regulations and legal ordinances , arose during Narām-Sin's reign . Dāduša fought successfully against Šamši-Adad I. After his death, Ibâl-pî-El II won important victories against Assur and Mari .

After a lost war, Eschnunna finally sided with the Elamites (with whom it formed coalitions), the Guteans , Subartus and Malgiums in 1763 BC. BC and 1761 BC Under the rule of Hammurabi of Babylon (30th - 32nd year of his rule).

End of the 18th century BC There were rebellions of the conquered cities among the successors of Hammurapis, in which Esnunna was also involved. In his 20th year of reign, Šamšu-iluna of Babylon defeated the warriors from Esnunna. A little later there were bitter defensive battles of the Babylonians against the Kassites , which penetrated unstoppably into the Babylonian territories. Eschnunna continued to exist as a city, but it completely lost its political independence and thus no longer played a role on the (world) political stage.

building

Šusîn temple

The Šusîn Temple (referred to as the Gimilsin Temple in earlier publications) was probably started by the governor of Ešnunna, Ituria, and completed by his son and successor Ilushuilia. Ituria built the temple for his lord, King Su-Sin of Ur, who was deified. A palace building was later built west of the temple, in front of which it stood vacant. To the west of the palace is a smaller temple called the "palace chapel", whose dedicated deity is unclear. The Šusîn temple is built on the principle of the hurdle house. One axis can be drawn from the cella, vestibule and gate. The temple has exceptionally thick walls and is decorated with signs of dignity on the gate and walls, while the "palace chapel" has thinner walls, but a higher number of rooms. It can be assumed that the "palace chapel" was used for everyday purposes and that the Šusîn temple was only used on certain occasions and only by a few people. After the Ur-III period and the various phases of renovation of the palace and temple, the temple walls still stood, but the premises were used for other purposes.

Abu temple

The name Abu Temple suggests that the place of worship with this name was dedicated to the deity Abu. The assignment is due to a hoard found during excavations in the 20th century near the temple. In a brick hiding place, archaeologists were able to safely store copper vessels that had been used in ritual acts. On one of the vessels they discovered the name of the god Abu. They suspected that the objects belonged to the temple and named the complex Abu Temple. However, the correctness of the assignment is not guaranteed.

Henri Frankfort divides the building history of the cult site into three phases:

- Archaic shrine,

- square temple and

- single shrine.

Archaic shrine

The first building of a temple at this point took place in the late Oemdet Nasr period around 3000 BC. Chr. And had an irregular floor plan, which was probably due to the densely built-up area. With the first renovation, the place of worship took on the structure customary for these buildings: an elongated room with an elevated altar on the narrow side far from the entrance. In front of it was a low altar in a round or square shape. A side extension with a sacristy and a front cell was part of it, as was an altar in the area of the forecourt.

Square temple

In order to be able to pay homage to various deities - including at least one goddess - at this place, Heinrich suspects that three sanctuaries with additional rooms were arranged so that the buildings surrounded a courtyard. This ensemble of buildings was known under the name "square temple". Under the floor of the temple, the archaeologists discovered several early dynastic round sculptures of various sizes, which they dated between 2800 and 2600 BC. Dated. This included a male, 72 cm high and a female, 59 cm high consecrated figure with extremely large eyes and very simplified bodies.

Single shrine

It has not yet been clarified why around 2400 BC. BC - in early dynastic times - the construction method of the "square temple" was abandoned and returned to a sanctuary, which consisted of a room and an attached sacristy. Later - in Akkadian times - the architecture known as the hearth house was changed again and the cult room was separated into anteroom and cella by an unusually thick wall with a central passage. As soon as the believer walked towards the cella from the anteroom, he was directly across from the cult image.

Ruler's palace

The palace of the rulers of Ešnunna was built by Ilušuilia, Ituria's son, next to the temple of Šusîn. It is probably not a residence, but served administrative purposes; there is no such thing as a clearly identifiable apartment. The main house of the palace consisted of a three-part system with a central hall, a "throne room" or reception room in front of it, a square courtyard and several side rooms. Clay tablets were found in the central hall and the adjoining rooms, which is why Lloyd interprets the side rooms as "government offices". The reception room has no furnishings, but can be interpreted as such due to its location between the courtyard and the central hall. To the north of the reception room there is a staircase built in later that led to the roof or an upper floor. To the west of the courtyard is the so-called "palace chapel", to which cleaning facilities are attached. Lloyd interprets the west corner of the palace and the north-west side of the courtyard as the royal quarters, which Heinrich considers unlikely due to the small size. What is striking about the palace is that it only has the most necessary facilities for normal business operations and a modest representation and is at the same time connected and designed with a richly furnished "palace chapel".

The palace was rebuilt several times over the years, so that among other things the "palace chapel" disappeared. At the time of Bilalama, the great state temple was secularized and absorbed into the palace, so that the buildings were connected. In addition to a few changes in the floor plan, most of the walls were still there, but the space is used for workshops. The staircase north of the "throne room" has disappeared, but there is a new residential area on the west corner of the palace complex, which is partly above the walls of the former "palace chapel". Not much of the latter has survived, in its place there is now a courtyard that leads into the main courtyard, although the meaning of the complex cannot be recognized. The residential complex is located on a terrace that can be reached by stairs. It is relatively clear that this is an apartment, but whether it is that of the ruler is doubtful. Heinrich suspects that the building was increasingly being misused and could have been used as a commercial building.

The north palace

In the north of Ešnunna, adjacent to a structure known as the city wall to the south, there is a building that, due to its size (approx. 75 m length) and time, was initially referred to by the excavators as the Akkadian Palace , later as the Northern Palace . However, it should not be a ruler's palace, as there is no throne room. The building was more likely to have housed a type of commercial enterprise in which stone and ceramic objects were made or fabrics were dyed. It should also have served as the owner's apartment. In contrast, however, it is perhaps interesting to observe that along the eastern row of rooms there were no less than 5 rooms with a connection to an elaborate sewage system - Heinrich calls them abortions - and a few other places where you could wash and that an Akkadian clay tablet, which was found in the rubble above the ruins of the house and whose text speaks of a 'women's shelter', could give an indication of the nature of this commercial facility.

Esikil Temple

The main sanctuary of the city was the temple called Esikil , which was originally dedicated to the god Ninazu . In the old Babylonian period Tišpak rose instead to become the main god of the city.

Early Dynastic Homes

An area (JK 18 - 21) in Ešnunna that did not contain any public buildings, but private houses from the early Dynastic period , is called a “private house area” . It is crossed by a main street, the so-called "Middle Road", on which the largest (and probably most affluent) of the houses were located. The smaller, poorer houses were built in the remaining spaces. The early dynastic strata (strata Va and Vbc) begin under the decadent strata of the Akkad period . They are marked by the occurrence of plano-convex bricks. Almost all house floor plans were shaped by two factors: the existence of earlier walls and the space that was left between existing buildings and streets. Existing walls were used as foundations for new buildings, in contrast to public buildings, for which “fresh” foundations were always laid. There are four types of houses that build on each other:

- The “single-flanked mainroom” type, consisting of one large room, flanked at the end by two smaller rooms (all examples from Layer Va).

- The “double-flanked main room” type, which is created by adding an area to the front (“front room”) (layers Va and IVb).

- The “fully-flanked main room” type, in which additional rooms are built on the sides that are still exposed (layer V-III).

- And the so-called “composite house”, which is created by enlarging by “adding” another house (e.g. Arch House layer Vc-a).

The houses consisted almost entirely of unfired bricks of various sizes and shapes. The thickness of the walls could also vary. In layer Vc-a, planoconvex bricks of various sizes were used, laid in a typical herringbone pattern. The floors were usually made of rammed earth, more rarely it was covered with plaster.

Based on the house size, three different ways of using the rooms can be determined:

- The entire complex measures less than 40 m² and consists of one or a maximum of two rooms with a stable-like character. These rooms probably served as a shop or stable rather than as apartments.

- This type measures between 40–100 m². Families lived here in a "single suite" with freely interconnected rooms.

- This house measures over 130–140 m² and was used for two purposes a) as large “single-suite” houses for wealthy families and b) as large “multi-suite” apartments for large families.

While these “multi-suite” apartments of extended families were located near temples or public buildings, poor families lived far away from these affluent districts in cramped neighborhoods. As a result, large families had considerable wealth and a certain status in their community.

Cooking took place in two places in the house a) in rooms with doorways or windows to the outside and b) in large central uncovered courtyards, as there was adequate ventilation. Cooking vessels and heat producing devices (such as a stove and oven) have been found in these locations. As well as serving and eating bowls. Cooking, serving and eating took place in the same areas of the house. Since there were no graves in the house, a burial outside the city walls is suspected. Isolated valuables (such as semi-precious stones, metal jewelry, vessels, stone sculptures) were found scattered across all room types. Seals and seal impressions, on the other hand, were mainly found in centrally located rooms. In Layer Va they were only found in "front rooms" and central rooms. One explanation for this would be receiving unrelated people and business deals in these same rooms. The first sanitary facilities were also found in particularly large houses.

Arched House

A door arch and a window have been preserved in the particularly well-preserved “Arched House”. The house is northwest of Mittelstrasse and was one of the wealthier houses. It existed in almost all of the epochs recorded there in only a slightly different form. It takes its name from some well-preserved arched doorways. The door dimensions vary from 0.45 to 1.50 m wide, the average is approx. 70 cm. The windows were rather narrow (about 25 cm). Not much can be said about the type of roofing as no meaningful remains have been preserved. Typical fireplaces were e.g. B. an open stove in a hollow in the floor or a V-shaped construction made of fired bricks, but also small closed ovens.

Finds

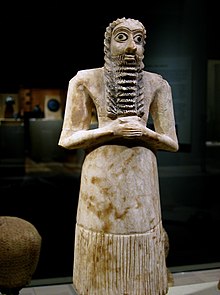

The finds in Ešnunna include stone sculptures of men, women and animals. They were found, partly in fragments, in the Singel Shrine Temple and Square Temple of the Abu Temple. In their immediate vicinity there was a deep bench, set in the temple wall. This suggests, as parallel finds in Aššur show that the sculptures were placed on it. However, the bank could also have been a kind of storage space for statues that were stored due to lack of space and differences in rank. The exact use of the statues could be determined by means of inscriptions on the shoulders of some almost completely preserved sculptures. They identified the statues as personified offerings by people to their god. In return, the makers of the statues asked for happiness and a healthy life. In addition to these personified statues, those with a mounting device were also found (Mythological Figures). These were probably temple inventory on or in which offerings were placed or placed. The personalized sculptures can be divided into two periods:

- Early Dynastic Period II.

- Early Dynastic Period III.

Early Dynastic Period II

The bodies were very abstract and geometrical, as the finer craft of stone and metal processing was not yet known. The torso is square with muscles slightly engraved and a straight line down the back to represent the structure. The hair is parted in the middle and falls on the shoulders. The beard is structured and painted in a black or brown color to clearly distinguish it from the rest of the face. The eyes were large and highlighted by an engraving of the eye sockets. Depending on the sculpture, there were individual differences and characteristics that should describe the owner and the person represented with it more precisely.

Early Dynastic Period III

The shapes became more fluid with smoother transitions. In addition to the already existing and drawn chest muscles, the collarbones and the approach on the neck to the head have now been worked out and displayed. The hair and the beard became more delicate and were given more natural gradients. The eyes were more smoothly connected to the face. The artists and sculptors also attached much more importance to the individual characteristics of their models. Similar finds could also be made in other cities. In addition to Hafagi, sculptures from the early Dynastic III period were also found in Lagasch and Aššur, as were the two statues of Lugalkisalsi from Uruk.

Women

These were a little easier for the sculptors to shape, as most of the body was covered with a cloth, so that one only had to partially show the structure of this cloth. The hair and jewelry of these statues were therefore sometimes more elaborate and detailed than those of the male ones. But here too the differences between II. And III. Period clearly visible because in the III. During the period the figure of women was also more clearly emphasized.

See also

literature

- Pinhas Delougaz, Harold D. Hill, Seton Lloyd: Private Houses and Graves in the Diyala Region (= Oriental Institute Publications . Volume 88 ). University of Chicago, Chicago 1967, p. 143-261 . on-line

- Henri Frankfort: Tell Asmar, Khafaje and Khorsabad: second preliminary report of the Iraq Expedition. Oriental Institute Communications, Volume 16 (OIC 16), Chicago 1933. online

- Henri Frankfort: Tell Asmar, Khafaje and Khorsabad: third preliminary report of the Iraq expedition. Oriental Institute Communications, Volume 17 (OIC 17), Chicago 1934. online

- Henri Frankfort: Sculpture of the Third Millennium BC from Tell Asmar and Khafājah . Oriental Institute publications, Volume 44 (OIP 44), Chicago, Illinois 1939.

- Ernst Heinrich: The temples and sanctuaries in ancient Mesopotamia: typology, morphology and history (= monuments of ancient architecture . Volume 14). de Gruyter, Berlin 1982.

- Ernst Heinrich: The palaces in ancient Mesopotamia (= monuments of ancient architecture . Volume 15). de Gruyter, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-11-009979-9 .

- Elizabeth F. Henrickson: Elite Residences in the Diyala Region . In: Mesopotamia. Rivista di archeologia, epigrafia e storia orientale antica. Volume 16, 1981, pp. 43-140.

- Elizabeth F. Henrickson: Elite Residences in the Diyala Region . In: Mesopotamia. Rivista di archeologia, epigrafia e storia orientale antica. Volume 17, 1982, pp. 5-33.

- Jason Ur: Southern Mesopotamia. In: Daniel T. Potts (Ed.) A Companion to the Archeology of the Ancient Near East. , Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester 2012, ISBN 978-1-4051-8988-0 , pp. 533-555.

- Robert M. Whiting: Old Babylonian Letters from Tell Asmar (Assyriological Studies 22). Chicago 1987. ISBN 0-918986-47-8 ( online ; PDF; 13.0 MB)

- Wu Yuhong: A political history of Eshnunna, Mari and Assyria during the early old Babylonian period: (from the end of Ur III to the death of Šamši-Adad). (= Journal of Ancient Civilizations , Supplement 1. ) Northeast Normal University, Changchun 1994.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Eduard Meyer : History of antiquity . Darmstadt 1965, 8th edition, Vol. 1/2, p. 554. Digitized

- ↑ Heinrich: The palaces in ancient Mesopotamia . 1984, p. 45

- ↑ Ernst Heinrich: The temples and sanctuaries in ancient Mesopotamia . Berlin 1982.

- ↑ Ur: Southern Mesopotamia . 2012, pp. 542-543

- ^ Frankfort: Tell Asmar, Khafaje and Khorsabad: third preliminary report of the Iraq expedition . 1934, p. 23 ff. Fig. 20

- ↑ Heinrich: The palaces in ancient Mesopotamia . 1984, p. 31 f.

- ^ Henrickson: Elite Residences in the Diyala Region . 1982, pp. 24-32

- ↑ Heinrich: The palaces in ancient Mesopotamia . 1984, p. 31

- ↑ Delougaz: Private Houses and Graves in the Diyala region . 1967, Pl. 37, 40

- ^ Henri Frankfort: Sculpture of the Third Millennium BC from Tell Asmar and Khafājah . 1939, p. 10

- ^ Henri Frankfort: Sculpture of the Third Millennium BC from Tell Asmar and Khafājah . 1939, p. 11

- ^ Henri Frankfort: Sculpture of the Third Millennium BC from Tell Asmar and Khafājah . 1939, pp. 20-22

- ^ Henri Frankfort: Sculpture of the Third Millennium BC from Tell Asmar and Khafājah . 1939, pp. 28-30

- ^ Henri Frankfort: Sculpture of the Third Millennium BC from Tell Asmar and Khafājah . 1939, pp. 30-33