Watch production in the Black Forest

The Black Forest clockmakers had until the late 20th century world of the second half of the 18th century meaning. Inexpensive large clocks from the Black Forest such as alarm clocks, grandfather clocks and wall clocks dominated domestic sales, but also exported to all over the world. Portable watches such as pocket and wristwatches only played a subordinate role. In terms of numbers, the pocket and wristwatches produced in the 20th century in the Pforzheim jewelery industry and by traditional clock manufacturers only play a subordinate role compared to the Swiss watch industry, which is the leader in this area. Therefore, only the development of the clock industry is described below.

history

First beginnings and development before 1730

The beginnings of the Black Forest watchmaking are in the dark. Although we find the names and places of residence of the first watchmakers in the Black Forest in the early chroniclers of local watch history, Father Franz Steyrer (1796) and Pastor Markus Fidelius Jäck (1810), the information provided by both of them is contradictory. It seems certain that the first Black Forest wooden clocks were made in the second half of the 17th century, after the end of the Thirty Years' War. However, due to renewed armed conflicts, watchmaking was only able to establish itself as an independent trade on a larger scale from around 1730.

Successful wooden clocks (1730 to 1840)

In the 18th and 19th centuries the manufacture of wooden clocks dominated. Wood was traditionally used in many rural areas of Central Europe as the basic material for making clocks. This is probably less due to the technical possibilities than to the legal requirements: The production of metal clocks was subject to the rules of the guild and was strictly limited to the city clockmakers. In contrast, wood watchmaking was a free trade. Everyone was allowed to build clocks out of wood. It is therefore not surprising that the first clocks in the Black Forest were made in the workshops of woodworkers. The reasons mentioned earlier for the emergence of watchmaking, the long, dreary winter evenings and the supposed inventive spirit of the Black Forest are consequently romantically transfigured ideal images.

The Black Forest wooden watches were successful worldwide. There are several reasons for this: On the one hand, wood was cheaper and easier to work with than metal, but this advantage also applied to other regions in which wooden watches were built. Another factor was decisive for the triumph of Black Forest clocks: the division of labor. A watchmaker was no longer solely responsible for the creation of the watches, but instead obtained prefabricated parts from suppliers. There were frame makers, foundries for bells and gear blanks, chain makers, sign makers and sign painters. These specialized craftsmen developed machines and tools with which series of similar blanks could be produced quickly and cheaply. This division of labor and new processes led to significantly higher productivity. As late as 1750, it took a watchmaker a whole week to make a watch. Thirty years later he was making one clock a day.

Until the second half of the 19th century, the wooden Black Forest clocks were made in many small workshops that were part of the residential buildings. Almost every owner employed a few journeymen and apprentices.

This development stagnated from the end of the 18th century. Despite improvements in the division of labor, the number of employees increased with the production figures (150,000 watches around 1800). Around 1840 there were around 1,000 watchmaker's houses with 5,000 employees in the area between Neustadt in the south and St. Georgen in the north. Every year around 600,000 wooden clocks are made - a large part of world production. Compared to other structurally weak low mountain ranges, there was no mass poverty in the Black Forest, which is why the "Black Forest watch production model" was considered successful among contemporaries.

Thanks to the inexpensive material wood, the use of machines and the division of labor, the Black Forest house industry achieved the worldwide price leadership for clocks. In the 19th century, the wooden clock with the brightly painted clock shield from the Black Forest was the cheapest clock on the world market.

Sales and export of Black Forest wooden watches

In addition to watchmaking, glassmaking was operated in the Black Forest and the products were sold at home and abroad by so-called glass carriers . Even the first Black Forest watchmakers used the distribution channels of the glass industry and gave their products to the trade. The watch dealers joined forces in several companies. The first Black Forest watch dealers appear from 1740. They settled in almost every country in Europe. They had the goods sent directly from the Black Forest and stored them centrally. After that, they wandered through the rural areas and markets, packed with a few watches. As a result, they also made a major contribution to the general spread of watches; the watch as a commodity changed its character from a luxury good to an everyday item.

The watch dealers noticed very quickly which types of watch were selling better than others in the various sales markets. In England, for example, watches with a date display and lacquer plates with little decoration were popular. Colorful dials sold best in France. And clocks with a black rim and typical motifs such as bullfighting were made for the Mediterranean region.

Structural Change and Industrialization (1840 to 1880)

House watchmakers and small workshops, who after all produced around 15 million watches in the first half of the 19th century, complained about their economic situation around 1840 and saw the causes in tariff increases and trade restrictions. In addition, many were dependent on the local wholesalers, the so-called “packers”, who took the finished watches from them and in return supplied them with components and everyday necessities - at sometimes higher prices, as the home traders complained. However, watch development had stagnated for a long time, and the lacquer shield watch, which had previously been well sold , no longer met the demands of customers.

As part of structural funding, the Baden state government founded the first German watchmaking school (1850–1863) in Furtwangen in 1850 in order to guarantee the smaller craftsmen a good education and thus to increase sales opportunities. Attempts were also made there to guide watchmakers to a greater division of labor and to establish a certain standardization of dimensions and shapes. But the school was not accepted by watchmakers in particular.

In the second half of the 19th century there were first signs of structural change, which was followed by a rapid transition to industrial watchmaking from 1880. In the years between 1850 a few small businesses developed on the threshold of a watch factory, manageable watch workshops with quality awareness that employed between 10 and 35 people. Well-known examples are Johann Baptist Beha , Lorenz Bob or Emilian Wehrle . These entrepreneurs set the tone in the trade associations that were gradually founded after 1850 , where they were involved, among other things, in railway construction and uniform work and workshop regulations.

The first actual watch factories were also built in the Baden part of the Black Forest. These include the Lenzkirch Aktiengesellschaft für Uhrenfabrikation , founded in 1851 , or L. Furtwängler Sons in Furtwangen (founded in 1868), which initially manufactured table and wall clocks such as regulators based on the French model. But the house trade continued to play a certain role, especially in the area of component manufacturing.

As a result, watch production was concentrated around a few centers. Even before the railway age began , advantages such as good traffic conditions and hydropower determined the choice of location in the Baden part of the Black Forest. The cities of St. Georgen, Triberg , Furtwangen , Titisee-Neustadt and Lenzkirch were able to benefit from this and grew. Rural commercial centers such as Eisenbach are developing again.

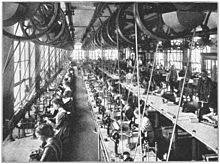

The heyday of the watch industry (1880 to 1914)

From 1880 there was a relocation to the Württemberg part of the Black Forest and the neighboring Baar plateau. Schramberg and Schwenningen developed into world centers for the watch industry. Well-known names in Schramberg were the Junghans company and the Hamburg-American watch factory , in Schwenningen the Kienzle and Mauthe companies . Schwenningen developed with companies such as the Württemberg watch factory Bürk or ISGUS to the production center of the control clock construction . The small businesses now lost much of their importance.

The main reason for the rapid rise of the Württemberg watch industry compared to the traditional production area in the Baden part of the Black Forest is to be seen in the innovative production method of new watch shapes. The alarm clock in a metal case developed into the parade horse of the Black Forest watch industry around 1900. While the first watch companies in the Baden Black Forest were still committed to making the solidity of traditional watch movements affordable through series production, the construction of the alarm clocks was entirely geared towards industrial mass production based on the American model. These new "American watches" were created using special machines to save material. The individual parts were optimized for the fastest possible assembly. The robust W10 alarm clock mechanism from Junghans, developed in the early 1880s, set new standards. It enabled Junghans to become "the largest watch factory in the world", as the Schramberg manufacturer called itself after 1900. The W10 alarm clock was produced in huge quantities until the 1930s and was only slightly modified by numerous other companies in the Black Forest. The alarm clock from the Black Forest became the cheapest clock on the market - like the wooden clock of the 19th century. Thanks to the alarm clock, the Black Forest already covered 60% of world exports of clocks before the First World War. The fact that there was no longer just one clock in every apartment - as was the case in the heyday of the wooden clock - but also "the right clock for every room" (according to an advertising poster from the 1930s) also contributed to the strong sales of the clocks became: clocks with washable housings for the kitchen, elegant wall and grandfather clocks, in wood to match the furniture of the “parlor”, or the alarm clocks for the bedrooms.

Crisis and Stagnation (1914 to 1945)

With the First World War , watch production largely came to a standstill. However, some watch companies such as Junghans or Kienzle continued to do good business with armaments such as time fuses .

The permanent economic crisis of the 1920s made life difficult for watch companies. Above all, the manufacturers of the Black Forest in Baden, who are oriented towards quality craftsmanship and consequently rather expensive and strongly export-oriented, had problems with the isolation of the foreign market by customs borders as early as the early 1920s. Domestic demand for high-priced clocks such as wall and grandfather clocks also fell sharply, while low-priced products such as alarm clocks continued to sell well. At the latest with the Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s, most Baden watch factories had to file for bankruptcy. These included the public limited company for watch manufacturing in Lenzkirch , Philipp Haas & Sons in St. Georgen or L. Furtwängler Sons and the Badische watch factory in Furtwangen.

Up until the beginning of the Second World War, the effects of the economic crisis were palpable. In 1935, domestic watchmaking sales were just 76% of the 1928 level; foreign demand remained at 50%.

The Second World War interrupted watch production again. It is known that in addition Junghans and Kienzle other companies in the watch industry as the Villinger watchmaker Emperor acquired Badische watch factory in Furtwangen, Müller & Schlenker (= EMES) and Jäckle in Schwenningen, Bäuerle in St. Georgen and Schatz & Sons in Triberg detonator buildings.

The decline of the watch industry (1945 to 2000)

The clock industry at the locations in the central Black Forest and on the Baar had survived the Second World War largely unscathed. The equipment of the companies with machines and material was usually excellent. The reparation demands of the French occupying power soon led to the evacuation of machines and a shortage of materials. But by 1949 85% of pre-war production had already been reached.

Despite this rapid recovery, the watch industry did not benefit from the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s to the same extent as the economy as a whole. Between 1954 and 1963 sales increased significantly from 428 million DM to 584 million DM. In relative terms, however, the share in the turnover of all industrial companies halved from 1.9% (1954) to 1.1% (1963).

Due to the high proportion of labor costs in watchmaking compared to other industries, the sharp rise in real wages in the decade between 1962 and 1972 had a negative effect on the earnings of the watch industry. All the more so since the mature technology no longer offered any fundamental scope for rationalization in order to make watch production cheaper. If you disregard the electronic components of battery clocks from the early 1960s onwards, gears and plates around 1970 were usually still manufactured according to principles that came from the pioneering phase of the clock industry in the late 19th century.

But within a decade, the manufacture of watch movements changed fundamentally. The traditional mechanical watch movements for everyday use were swept from the market by two waves of innovation in the 1970s. Plastic took the place of metal, electromechanics and then the microelectronics of quartz watches took the place of mechanics. Anyone who, as a watch manufacturer, stayed with conventional precision mechanics and did not manage to switch to the new materials and technologies had to file for bankruptcy within a few years. In the mid-1970s, it was primarily watch companies that went bankrupt that for the most part still built mechanical watch movements in the traditional manner: 1974 the Josef Kaiser alarm clock factory in Villingen, 1975 Blessing in Waldkirch, 1976 Mauthe in Schwenningen.

The realization that the production of mechanical clockworks will come to an end developed as early as the 1960s through the construction of battery-powered first motor-lift, then rotary oscillator clockworks. Several larger, but also small German watch manufacturers with only a few employees developed battery works for table and wall clocks of all styles. The longest mechanical works could keep up with alarm clocks until the 1990s. B. from Adolf Jerger in Niedereschach .

The state of Baden-Württemberg directly and indirectly supported the conversion of manufacturers such as the Kienzle company in Schwenningen. With the support of the Fraunhofer Institute, several manufacturers have been able to mass-produce quartz movements for alarm clocks, table clocks and wall clocks. The only manufacturers who went from mechanical to electromechanical to quartz clocks were Junghans, EMES, Andreas Haller and (with a significant delay) Kienzle. Smaller and previously insignificant manufacturers such as the Staiger brothers and Andreas Haller in St. Georgen were particularly successful in developing quartz watches, who consistently used plastic quartz watches in fully automatic production and were thus able to gain a decisive advantage in terms of experience. Together with the local competitor Kundo, Staiger financed the UTS company with the aim of inexpensive manufacture of quartz movements. In 1985 the watch production was fully automated for the first time. It allowed an unrivaled low-cost production. But other manufacturers, such as EMES in Schwenningen, succeeded in mass production of quartz movements.

Germany's technological lead in the manufacture of quartz movements was lost in a very short time. After the bankruptcy of EMES and Kienzle, the production facilities for quartz watch movements were sold to China by the bankruptcy administrators and rebuilt there. By importing the cheapest quartz movements from China, other manufacturers in Germany came under considerable pressure: Junghans brought its quartz movement production into the joint UTS-Junghans GmbH in 1996; Kienzle went bankrupt that same year. The Kundo and Staiger companies (merged to Kundo-Staiger in 1992) could no longer keep up in terms of price. In 2000 Kundo-Staiger also had to file for bankruptcy. UTS also had to downsize considerably and was relocated to Dunningen near Rottweil.

In 2009, of the original 32,000 jobs in the Black Forest watch industry (1970), just 1,369 employees were left.

Except for a few remains, the once so proud watch industry has disappeared today (as of 2016): In 2016, one of the last manufacturers of mechanical watch movements in southern Germany, with around 40 employees, was the Josef Kieninger company in Aldingen near Rottweil, as well as the Hermle watch factory in Gosheim , which also manufactures clocks for living room clocks (both not in the Black Forest, but in the Swabian Alb ). The last manufacturer of quartz movements is also in 2016 the company Uhrentechnik Schwarzwald Montagetechnik (formerly UTS) with around 15 employees in Dunningen near Rottweil. The last manufacturer of mechanical movements for cuckoo clocks is the company SBS-Feintechnik (formerly Josef Burger Söhne) in Schonach .

Watch manufacturer in the Black Forest

The German Clock Museum in Furtwangen probably houses the most comprehensive collection on the history of Black Forest clocks from early wooden clocks to electromechanical clocks to quartz and radio clocks from the last decades of the 20th century.

The touristic circular route German Clock Route connects memorial sites on the history of the Black Forest clock and places of clock production in the Black Forest and on the Baar.

Former major German watch manufacturers

- Aktiengesellschaft für Uhrenfabrikation Lenzkirch

- Andreas Haller GmbH & Co. KG (1925 - 2004)

- Gustav Becker

- Badische Uhrenfabrik Furtwangen AG (BADUF)

- Johann Baptist Beha (1815–1898)

- Tobias Bäuerle & Sons (1864–2001)

- Lorenz Furtwängler sons

- Thomas Haller

- Thomas E. Haller

- Hamburg-American watch factory (HAU)

- Mauthe

- Watch factory Villingen AG

- Winterhalder & Hofmeier

- Alois Duffner Sons cuckoo clock factory, Schönwald

Other manufacturers names: Hans Heinrich Schmid: Lexicon of the German watch industry. 1850–1980, 3rd expanded edition, 2 volumes, Berlin 2017.

Active watch manufacturer in 2016

- AMS-Uhrenfabrik A. Mayer GmbH, Furtwangen (living room clocks)

- Engstler e. G. (cuckoo and Black Forest clocks)

- Hanhart , Gütenbach (stopwatches and wristwatches)

- Hermle clocks, Gosheim (living room clocks)

- Hubert Herr, Triberg (cuckoo and Black Forest clocks)

- Robert Herr, Schonach (cuckoo and Black Forest clocks)

- Hönes GmbH, Titisee-Neustadt (cuckoo clocks and Black Forest clocks)

- ISGUS GmbH , Villingen-Schwenningen (time recording systems)

- Junghans (wristwatches and designer watches)

- Helmut Kammerer, Schonach (cuckoo and Black Forest clocks)

- Kieninger clocks, Aldingen (living room clocks)

- Lehmann precision clocks, Schramberg (wristwatches)

- Rombach & Haas , Schonach (cuckoo and Black Forest clocks)

- Anton Schneider & Sons, Schonach (cuckoo and Black Forest clocks)

- August Schwer, Schönwald (cuckoo and Black Forest clocks)

- Uhrentechnik Schwarzwald Montagetechnik GmbH, Dunningen (quartz clockworks)

literature

- Hans Heinrich Schmid : Lexicon of the German Watch Industry 1850 - 1980 , 3rd expanded edition, 2 volumes, Berlin 2017 ISBN 978-3-941539-92-1

- Gerd Bender: The watchmakers of the high Black Forest and their works. Volume 1, Villingen 1976, ISBN 3-920662-00-8 , Volume 2, Villingen 1978, ISBN 3-920662-01-6 .

- Johannes Graf, Eduard C. Saluz: Black Forest clocks - good and cheap. Furtwangen 2013, ISBN 978-3-922673-32-3 .

- Herbert Jüttemann: The Black Forest Clock . Badenia-Verlag, Karlsruhe 2000, ISBN 978-3-89735-360-2 .

- Helmut Kahlert: 300 years of the Black Forest clock industry , Gernsbach 2007, ISBN 978-3-938047-15-6 .

- (en) Rick Ortenburger: Black Forest Clocks. Schiffer Publications, Ltd, Atglen, Pennsylvania, USA, 1991. ISBN 0-88740-300-X .

- Berthold Schaaf: Black Forest clocks. Karlsruhe 2008. ISBN 978-3-7650-8391-4 .

Web links

- The German Clock Museum in Furtwangen in the Black Forest

- Inventor times - clock museum in Schramberg

- (en) Private collection of historical Black Forest clocks in the USA

- (cz) Private collection of historical Black Forest clocks in Bohemia

Individual evidence

- ↑ Helmut Kahlert: 300 years of the Black Forest clock industry, 2nd completely revised and updated edition, Gernsbach 2007, pp. 22-25.

- ^ Berthold Schaaf: Holzräderuhren, Munich 1986, pp. 9-14.

- ↑ Helmut Kahlert: 300 years of the Black Forest clock industry, 2nd completely revised and updated edition, Gernsbach 2007, pp. 59–70.

- ↑ Helmut Kahlert: 300 years of the Black Forest clock industry, 2nd completely revised and updated edition, Gernsbach 2007, p. 43.

- ↑ From house trade to watch factory. Romulus Kreuzer (1856) and Franz Reuleaux (1875) on the state of Black Forest watchmaking. Introduced and commented by Franz Herz and Helmut Kahlert, Furtwangen 1989, p. 7.

- ^ Berthold Schaaf: Schwarzwalduhren, Karlsruhe 2008, p. 126.

- ↑ Helmut Kahlert: 300 years of the Black Forest clock industry, 2nd completely revised and updated edition, Gernsbach 2007, p. 114.

- ↑ Helmut Kahlert: The Grand Ducal Badische Uhrmacherschule zu Furtwangen 1850–1863, in: Ders .: "For the sake of the clock friend. Scattered contributions to the history of the clock, edited by Johannes Graf, Furtwangen 2012, pp. 56–75.

- ^ Johannes Graf, Eduard C. Saluz: Black Forest Clocks - good and cheap, Furtwangen 2013, p. 33.

- ↑ Helmut Kahlert: 300 years of the Black Forest clock industry, 2nd completely revised and updated edition, Gernsbach 2007, p. 273.

- ↑ Helmut Kahlert: 300 years of the Black Forest clock industry, 2nd completely revised and updated edition, Gernsbach 2007, p. 274.

- ↑ Helmut Kahlert: 300 years of the Black Forest clock industry, 2nd completely revised and updated edition, Gernsbach 2007, p. 278.

- ↑ Like the following: Johannes Graf: From one hundred to zero in 40 years. The German clock industry in the post-war period, in: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie. Jahresschrift Vol. 50, 2011, pp. 241–262.

- ^ Hans-Heinrich Schmid: Lexicon of the German Watch Industry 1850-1980, Volume 2, Pages 342 and 609 .

- ^ Hans-Heinrich Schmid: Lexicon of the German Watch Industry 1850-1980, Volume 2, page 91 .