Vinča sign

Vinča signs or Vinča symbols are prehistoric signs of the Vinča culture that were found in south-eastern Europe . They are dated from around 5300 to 3200 BC. Dated.

The assumption that these are characters is questioned due to the shortness of the character series (85% of the finds consist of only a single character) and the lack of repeated symbols . Most experts assume that the Vinča characters represent a kind of script forerunner, ie that they contained a message, but did not yet depict any linguistic utterances. A minority, such as Harald Haarmann or Marija Gimbutas, consider it an old European script and classify it as a variant of a " Danube script ".

The discovery

In 1875 archaeologists discovered many objects with previously unknown symbols during excavations in Turdaș (now Romania ). A similar find was made in 1908 in Vinča , a suburb of Belgrade , about 120 km from Turda . Later other finds were made in Banjica near Belgrade. To date, more than 1000 pieces with such symbols have been found on various archaeological sites in Southeast Europe, especially in Greece , Bulgaria , Romania, the Republic of Moldova , in eastern Hungary , in southern Ukraine and in Serbia .

The finds

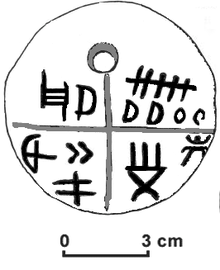

Most of the signs were found on ceramic vessels and small figures; few on other carrier objects. The characters consist of abstract symbols (crosses, lines, etc.), pictograms (e.g. animal-like images) and comb or brush patterns. Some of the objects contain several symbols that are not arranged according to any recognizable principle. Individual symbols are mostly found on pottery, while groups of symbols are on whorls .

Significance of the finds for the history of writing

In general, the knowledge or use of a script is assigned to the high cultures . This is done on the reliable assumption that only complex societies etc. a. Had to record administrative files and invented drawing systems for this purpose. According to current knowledge, this does not apply to the Vinča culture.

The significance of the finds is that they are dated to around 1000 years before the emergence of the oldest sign systems identified as writing systems (such as that of the Sumerians ). A comparison with characters from the Middle East shows that the characters originated independently of the Sumerian civilization. Some similarities can be noted to symbols of other Neolithic sign systems found in Egypt, Crete, and even China. However, Chinese scholars suggest that different cultures produced such characters independently. Accordingly, they represented at best a development leading to what could be called a forerunner of writing. In Sumer, calculi (counting stones) with symbols are the forerunners of the characters.

Although a large number of symbols have been found overall, most finds consist of very few symbols standing together, making them very unlikely to represent complex text. The only exception is a stone found near Sitowo (Northeast Bulgaria) with about 50 characters. Apart from the controversial dating, it cannot be determined whether the signs represent written information at all.

Interpretation of symbols

The meaning and purpose of the symbols are unclear. Whether it is a script system is debatable. If so, the question would be whether it logograms , syllables sign or alphabetical are signs. Attempts to decipher the symbols did not lead to generally accepted results.

At first it was assumed that the characters were nothing more than owner symbols (like branding). A prominent proponent of this opinion is the archaeologist Peter F. Biehl. This theory has been largely abandoned because the same symbols have been found throughout the area of the Vinča culture, sometimes hundreds of kilometers apart and separated by centuries. The prevailing theory assumes that the symbols in a farming society served religious purposes, i.e. were hierograms . The symbols were used for centuries with minor changes. The culture and rites that the symbols represent have therefore also remained constant for a very long time, apparently without any reason for development.

The use of the signs seems to have been abandoned at the beginning of the Bronze Age (along with the objects on which they appeared). The new technology probably brought about far-reaching social and religious changes.

One argument against a cultic meaning of the sign bearers is that the objects on which they are located are usually found in waste places, so that they should not have had any lasting meaning for their owner.

Certain items, mostly small statues, were often found buried under houses. This suggests that they were made for religious ceremonies pertaining to the house . By incising characters, the characters were assigned to a specific deity in the polytheistic pantheon , to whom wishes and hopes were directed. At the ceremony, the items were ritually buried (which some interpret as sacrifice).

Some of the so-called comb and brush symbols, which make up about a sixth of all symbols discovered so far, could represent numbers. Scientists point out that a quarter of the characters are on the bottom of ceramic vessels, a place that is not exactly obvious in our way of thinking for religious symbols.

The Vinča culture seems to have spread its ceramics through bartering. The vessels drawn were found in an extensive area. Early cultures such as the Minoan or Sumerian originally used their scripts for accounting purposes. The Vinča symbols could have served a similar purpose.

Other symbols, mainly those that are only found on the bottom of the vessel, are unique. Such symbols may indicate the manufacturer of the vessels.

The controversy

The Vinča characters did not attract as much attention from linguists as other well-known, undeciphered scripts, for example Linear-A or the Rongorongo of Easter Island . Even so, the material was likely to spark controversy.

The archaeologist Marija Gimbutas (1921–1994), who also coined the term “old European writing”, was one of the main proponents of the opinion that the characters were written. Harald Haarmann also represents this in his Universal Geschichte der Schrift (1990) and in his more recent works.

Most archaeologists and linguists disagree with the interpretation given by Gimbutas and Haarmann. A theory that is only occasionally discussed controversially comes from Radivoje Pešić, Belgrade. In his book The Vinca Alphabet he states that all Vinča symbols are contained in the Etruscan alphabet and vice versa, that all Etruscan characters can be found under the Vinča symbols. This thesis is hardly discussed, however, since the Etruscan alphabet is derived from the West Greek and the latter from the Phoenician writing system. This, in turn, is compatible with Pešić's point of view, since part of his theory of continuity says that the Phoenician system descended from that of the Vinča culture. Pešić has been accused by critics that his support for the continuity theory has nationalist motives.

literature

- John Chadwick : Linear B and related scripts . 3rd pressure. British Museum Press, London 1995, ISBN 0-7141-8068-8 , ( Reading the past ).

- JL Chapman: The Vinča culture of South-East Europe. Studies in chronology, economy and society . British Archaeological Reports, Oxford 1981, ISBN 0-860-54139-8 , ( British Archaeological Reports (BAR), International series 117, ISSN 0143-3067 ).

- Christa Dürscheid: Introduction to handwriting linguistics. 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, pages 104-106: The old European script . ISBN 3-525-26516-6 .

- Marija Gimbutas: The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, 6500 to 3500 BCE. Myths and Cult Images. 2nd ed. University of California Press, Berkeley 1974, ISBN 0-500-27238-7 , p. 17.

- Harald Haarmann : Early civilization and literacy in Europe: an inquiry into cultural continuity in the Mediterranean world , Berlin [u. a.]: Mouton de Gruyter, 1996, ISBN 3-11-014651-7 .

- Harald Haarmann: History of the Flood. On the trail of the early civilizations . CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49465-X , pp. 95ff.

- Harald Haarmann: Introduction to the Danube script . Buske, Hamburg 2010. ISBN 978-3-87548-555-4 .

- Martin Kuckenburg: Who spoke the first word? The emergence of language and writing . Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1852-8 , p. 122ff.

- Radivoje Pešić: Vinčansko pismo i drugi gramatološki ogledi . 6th edition. Pešić i Sinovi, Beograd 2003, ISBN 86-7540006-3 , ( Biblioteka Tragom Slovena 1), (Before: The Vincha Script . Pešić, Beograd 2001, ISBN 86-7540-006-3 ).

- Shan MM Winn: Pre-writing in Southeastern Europe. The sign system of the Vinča culture, approx. 4000 BC . Western Publishers, Calgary 1981, ISBN 0-919119-09-3 .

Web links

- Vinca symbols at omniglot.com, including font

- Eric Lewin Altschuler: The Number System of the Old European Script

Individual evidence

- ↑ Haarmann 2010, p. 10.

- ↑ Gheorghe Lazarovici, Marco Merlini: New archaeological data referring to Tărtăria tablets , in: Documenta Praehistorica XXXII, Ljubljana 2005, online (PDF) here ( Memento of the original from July 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Erika Qasim: The Tărtăria tablets - a reassessment . In: Das Altertum , ISSN 0002-6646 , Vol. 58, 4 (2013), pp. 307-318.