Conscription in Australia

The conscription in Australia ( English: Conscription ) existed in the past repeatedly rise to political conflicts. There were two armies in Australia from 1903 to 1980. There was the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), which consisted of volunteers who could be deployed anywhere in the world. This army fought in the First and Second World War outside Australia overseas. There was also the Commonwealth Military Force (CMF), also called Militia , which was only allowed to be used in an attack on Australian territory and consisted of conscripts . In the political disputes since 1903 it was about using the Commonwealth Military Force outside of Australian territory. To this day, the Australians prevented the army from being used outside their state.

Before 1914

In the wake of the Crimean War (1853-1856), the colonial government of South Australia passed the Militia Act 1854 , which empowered men to take part in military exercises over four weeks. For many years until the Defense Act 1894 was passed, it was unclear whether it would be permissible to use them outside of South Australia. It was only after this law came into force in 1894 that those obliged to exercise could be ordered to serve in other Australian colonies. In 1896, compulsory national self-defense became legally binding in South Australia. In the Second Boer War (1899-1902) in South Africa , which was characterized by brutal warfare and the introduction of the first concentration camps by Great Britain , Australia provided 16,400 soldiers, of whom 533 were killed and 583 wounded. With this experience, Australia, which became an independent state in 1901, passed the Defense Acts of 1903 and 1904. The 1903 law stipulated that conscripts could only be used within Australian territory. The Australian Freedom League , in which Quaker and several Christian religious groups were organized, was vehemently opposed to compulsory military service . A peacetime military service law was passed by the Australian Parliament during the reign of Prime Minister Alfred Deakin in 1909. In the wake of the international conflicts before World War I, the commitment found broad support from all parliamentary forces, including the opposition Labor Party.

When the Australian Labor Party was elected the ruling party, it made conscription for young men aged 12 to 26 years from January 1, 1911. This arrangement was circumvented in reality, because although around 350,000 young Australians between the ages of 10 and 17 were affected in 1911–1915, only around 175,000 took up this service.

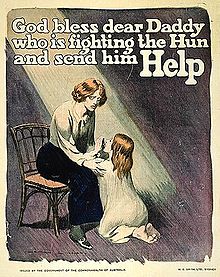

First World War

When the First World War began, so many Australian volunteers volunteered that not all of them could be accepted. The export-dependent economy of Australia, especially the sale of wood and raw materials for European markets, declined during the war and workers were made redundant. These workers formed the military's recruiting potential. Unemployment and inflation in Australia continued to rise during the war.

Reports of rising war casualties and details of the Battle of Gallipoli (the invasion began on April 25, 1915; a bloody stalemate developed in the trench warfare until the end of August) and the further course of the war became known. The war euphoria sank and there were hardly any volunteers. As early as July 1915, tens of thousands of young men refused to register for service in the Commonwealth Military Force.

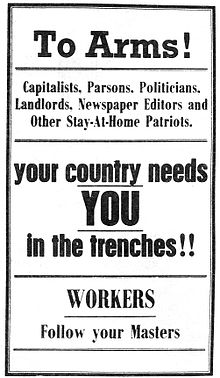

In this situation, the government of Prime Minister Billy Hughes , a member of the Australian Labor Party, decided to hold a referendum (popular vote) to enforce compulsory military service for all men aged 18 to 60. This political proposition sparked heated debates in Australia. The majority of the Australian Labor Party opposed it. Frank Tudor , leader of the Labor Party, resigned from the Hughes administration because of these policies. James Scullin , a later Prime Minister of Australia, called for all Labor Party members who are for conscription to be expelled. Chris Watson , a former Prime Minister and co-founder of the Labor Party, has been expelled for his supportive stance on conscription.

The referendum took place on October 28, 1916 and ended with 1,087,557 votes in favor and 1,160,033 against. With this result, it was not possible for conscripts outside Australia to participate in the war. After Hughes was expelled from the Labor Party on November 14, 1916, he founded the National Labor Party with other expelled Labor Party members and thereby remained Prime Minister in a minority government . The National Labor Party merged with the Commonwealth Liberal Party on February 17, 1917 to form the Nationalist Party of Australia, led by Hughes.

The domestic political climate worsened after the lost referendum and the War Precautions Act 1914 was applied. This law made it possible to arrest those who opposed the “defenselessness of Australia” in word and in writing. This resulted in the arrests of journalists and members of socialist parties, such as John Curtin , who at the end of 1916 did not register for possible military service and was therefore briefly imprisoned. Curtin became Prime Minister of Australia in the fall of 1941. The opponents of conscripts abroad were actively supported by the Archbishop of Melbourne Daniel Mannix , the Prime Minister of Queensland Thomas Joseph Ryan and by most of Australia's trade unionists .

The soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were used for the first time in combat on the Western Front (Belgium / Northern France) in July 1916 and experienced a very bloody “ baptism of fire ” in Fromelles and Pozières on the Somme . The enormous losses - 28,000 men in seven weeks - stirred up Australian society and, a few months later, led to the failure of a referendum to introduce compulsory military service.

In the course of 1917, in addition to the harsh winter and difficult living conditions in the trenches, the Australians suffered other victims: first on the Bapaume-Bullecourt section and then in the “Mudhole of Passchendaele” in Belgium.

During the retreat of the Germans to the Siegfried Line on March 19, 1917, the advancing Australians reached the burned-out city of Bapaume. They tried to catch up with the retreating Germans and took the villages of Vaulx-Vraucourt, Morchies and Beaumetz, which were now in ruins. In doing so, they repeatedly came across the enemy rearguard , with whom they fought bloody delayed battles in Lagnicourt, Noreuil and Hermies. Finally, on April 9, 1917, they reached the Siegfried Line with its dense barbed wire belts, deep trenches, concrete shelters, machine-gun nests and tunnels.

In 1917 Hughes intended to set up a 7th Australian Division, for which he needed 7,000 men. He put another referendum on December 20, 1917. The goal of this vote was to force all Australians aged 20 to 44 to serve in arms outside of Australia. A heated debate ensued that again split the country into two camps. This referendum ended with 1,015,159 votes in favor and 1,181,747 against. The rejection was more pronounced than on the occasion of the first vote. This made Australia, along with South Africa, a nation during the First World War that could not send any conscripts to war.

Second World War

After the start of World War II, the Conservative Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced on October 2, 1939 that all unmarried men under the age of 21 would be called up for three months of military training with the Commonwealth Military Force starting January 1, 1940. The men could only be used on Australian territory due to the prevailing legal situation. On November 15, 1939, Menzies announced that Australia would need an active force of 75,000 men in World War II.

Under the influence of the war, a law was passed in mid-1942 that allowed all men between the ages of 18 and 35 and all unmarried men between the ages of 35 and 45 to be drafted into the Commonwealth Military Force. Another law was passed in February 1943, called "Australia", which opened up the possibility of deploying military forces of the Commonwealth Military Force outside the continent of Australia. However, only in an area that was defined as the Southwest Pacific Area . They were areas southwest of the equator of Australia. Since New Guinea was part of Australian territory at the time and Japanese combat units attacked there, the Commonwealth Military Force could be used. There was high Australian loss of life in New Guinea. Under the impression of the bombing of Australia by Japanese air fleets and 20,000 captured Australian soldiers in 1943, the passage of this law led to only isolated protests. The Australians accepted this legal regulation in their majority until the end of the Second World War.

Post-war development

After the war ended, the Australian military personnel were demobilized until the end of November 1946. The government of Robert Menzies issued the National Service Act 1951 against the backdrop of the Korean War . All men born in Australia after November 1, 1950, were required to do 176 days of military service by the age of 18 and to be on reserve for five years. They could not be used in combat missions overseas. The regular army continued to consist only of volunteers. From 1951 to 1959, 500,000 young men were registered as draftees and only 227,000 men served in the Commonwealth Military Force. The National Service Act of 1951 was repealed in 1959.

Vietnam War

On November 5, 1964, at the time of the Vietnam War , the Conservative government of Robert Menzies issued the National Service Act (1964) . All 20-year-old men were to serve in the Commonwealth Military Force for 24 months, followed by three years of available reserve. In 1971 this service was shortened to 18 months.

According to the Defense Act of May 1965, the conscripts could be obliged to serve overseas (again limited to the so-called South-West Pacific Area - which did not include Vietnam). In March 1966, the government announced that the Commonwealth Military Force conscripts could fight in the regular Australian Army or serve in support of the US Armed Forces in Vietnam and were free to serve in the Commonwealth Military Force within Australia to choose. Between 1965 and December 1972 over 800,000 Australians served in the Commonwealth Military Force, of which only 19,450 volunteers chose to serve in Vietnam. Of them, 200 were killed and 1,279 were wounded.

Against conscription and the use of Australians in the Vietnam War, the movement developed Save Our Sons (: German Save our sons ) in the late 1960s. It originated first in Sydney , later in Melbourne , Brisbane , Perth , Newcastle and Adelaide . In 1970 five members of this movement were arrested in Melbourne for distributing leaflets against conscription. Young men formed an anti-conscription organization, the Youth Campaign Against Conscription . The nation was divided. A staunch opponent of Australia's participation in the Vietnam War and conscription was Jim Cairns . He was the most dedicated organizer of the campaigns against the Vietnam War and was attacked for his stance in his home and was ill for months afterwards. Around 1969, Australian public opinion turned against the Vietnam War. Individual young Australians, such as John Zarb, who was sentenced to prison for refusing to do military service, and actions against the Vietnam War with the participation of Australian unions, especially the Maritime Unions , raised public awareness. On May 18, 1970, 150,000 to 200,000 people protested against Australia's participation in the Vietnam War, 100,000 of whom protested in Melbourne alone.

In October 1970, opposition leader Gough Whitlam declared that he would withdraw all Australian troops from Vietnam if he is elected. When Whitlam was elected Prime Minister, the new Labor government under him revoked conscription to the Commonwealth Military Force in late December 1972.

Since 1980

The Commonwealth Military Force was renamed the Army Reserve in 1980 and adapted to the structures of the Australian Army. Today's Australian Army, the Australian Defense Force , comprises around 53,000 soldiers.

Web links

- Conscription during the First World War, 1914-18, on Australian War Memorial

- and Vietnam War

- The Homefront on john.curtin.edu.au

- Conscription on Anzac.org.au ( Memento from March 16, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Pouyan Vahabi-Shekarlooh: The South African Boer War and the English responses. Grin-Verlag 2005. ISBN 978-3-640-11646-1 , p. 8 f.

- ^ Fact sheet 160 - Universal military training in Australia, 1911-29 , accessed February 21, 2010

- ^ John Barrett (1979): Falling in: Australians and 'boy conscription', 1911-1915 , Hale & Iremonger, ISBN 0-908094-56-6

- ↑ Fact sheet 161 - Conscription referendums, 1916 and 1917 , accessed on February 22, 2010

- ↑ www.wegedererinnerung-nordfrankreich.com The two battles of Bullecourt ( Memento of October 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Fact sheet 162 - National service and war, 1939–45 , accessed February 21, 2010

- ↑ Information on diggerhistory.info , accessed on February 20, 2010

- ^ A b Conscripton on Australian War Memorial , accessed February 24, 2010

- ^ Encyclopedia Appendix: The national service scheme, 1964-72 Sue Langford: Australian War Memorial , accessed February 21, 2010

- ^ Fact sheet 163 - National Service, 1951-59 , accessed February 21, 2010

- ^ Fact sheet 164 - National service, 1965-72 , accessed February 21, 2010

- ↑ Save Our Sons: Information on womenaustralia.info , accessed on February 21, 2010

- ^ Australian Draft Resistance and the Vietnam War - statements by Michael Matteson and Geoff Mullen , accessed February 23, 2010

- ^ Tony Duras: Trade unions and the Vietnam war , accessed February 23, 2010