Weather anomalies of the 1430s

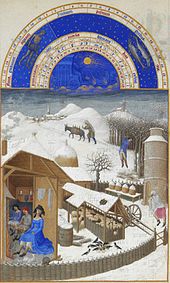

The winters of 1431 to 1440 during the Hundred Years' War were probably the coldest in north-western and central Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries. The weather anomalies of the 1430s with very cold and extremely long winters were interrupted by warm, rainy summers. It was probably random fluctuations in the weather system that led to this marked deterioration in the climate. The consequence of the weather anomaly was the famine of 1437–1440 , which claimed hundreds of thousands of deaths in the unprepared population.

Cold, long winters and summers with a lot of rain

At the beginning of the 15th century, life in Europe had improved after epidemics had decimated the population. One hoped for work and a livelihood. But the 1430s turned into one of the toughest decades.

On November 20, 1431, all rivers in Northern and Central Europe were frozen, including the Danube , Rhine and Lake Constance (→ Seegfrörnen des Lake Constance ). Wolves migrated from Norway to Denmark and further south across the frozen Baltic Sea . Even the Venetian lagoon could be crossed on foot from January 6th to February 22nd, 1432. In France the vines froze to death. Since hardly any snow had fallen during the winter, the sown seeds were exposed to extreme cold due to the lack of an insulating snow cover and most of them spoiled. In many places, winter lasted until March or April. The meltwater in the rivers accumulated into high water that flooded the cities. Places along the Danube were particularly hard hit. For Hungary , it is assumed that this decade was the second most flooded in the entire Middle Ages. The prolonged rain in the summer of 1432 caused the remaining harvest to rot. The famine began in Bohemia in 1432 . In other places in Europe the storages were still full. One year later, however, after another hard winter, all trade chronicles from Dublin to Cologne and Magdeburg to Prague are recording sharply rising prices for grain. In the winter of 1432/33 in Scotland the wine had to be thawed in order to be able to drink it. Other unusually cold and long winters followed. In Central Europe, rivers like the Rhine and large lakes like Lake Constance and Lake Zurich froze over in 1435 . In 1435, the lack of grain forced bread to be made from tree bark. Even in northern Italy and southern France the winter weather lasted until April, only the south of the continent was partially spared.

Consequences of ten-year weather anomalies

The consequences of the harsh weather for almost a decade were devastating for the people in Europe who were completely unprepared for such an event. Poor harvests and hunger contributed to the development of epidemics. The low temperatures and repeated frosts during the late spring impaired the growth of grain, and vineyards and other agricultural goods also suffered from the cold. Harvest failures occurred in England, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Bohemia and Switzerland. As a result, food prices rose significantly, leading to the worst European famine of the 15th century between 1437 and 1440. The weakened people became susceptible to illnesses and the damp summer weather provided the best conditions for dangerous germs. Hunger and epidemics killed hundreds of thousands of people and farm animals. The population in Europe fell to its lowest level in the 15th century. In the city of Bern, which has 5,000 inhabitants, more than 1,100 deaths were recorded from August to Christmas 1439.

It is no longer possible to reconstruct which diseases and epidemics were the main causes of death. In the chronicles every disease was referred to as "pestis" ( epidemic ). However, it can be assumed that the population suffered from respiratory diseases, among other things. However, some of the deaths may not be due to an infection of the respiratory tract, but to poisoning with ergot fungus ( Claviceps purpurea ). Ergot fungus attacks grain when the weather is too humid. The symptoms of this poisoning were known as the Antonius fire in the Middle Ages .

In their distress, the desperate population turned to the Church, where they found support and consolation in faith. It made minorities and outsiders guilty. The vernacular said that the gypsies who had just immigrated had the magical power to influence the weather. Fear and aggression erupted in pogroms against Jews and women who were persecuted as witches .

The struggle for food caused clans who were friends in the Scottish Highlands to go to war against each other and in the Old Confederation , Zurich imposed a grain ban on Schwyz and Glarus in the spring of 1438 , which was particularly difficult in the famine year 1438. This dispute eventually led to the Old Zurich War .

However, people also adapted to the cold weather. Newly built granaries helped cities such as Basel, Strasbourg, Cologne and London to survive poor harvests better. Emergency plans were also drawn up, including the import of food from distant countries. Nevertheless, the consequences of the disaster decade remained noticeable for a long time.

Cause of the weather anomalies

Historians and climate researchers from all over Europe have investigated the question of why the decade after 1430 was perhaps the coldest decade of the past millennium in north-western and central Europe. A comprehensive climate model was created on the basis of representative data from climate archives , tree ring , lake sediment and stalactite analyzes as well as historical documents from all over Europe . The models confirmed that the climatic conditions at the time were "very special". In the examined period from 1300 to 1700 there was therefore nothing comparable. Whether the 1430s was actually the coldest period in the past millennium could not be proven. Possible reasons for this anomaly would be dust particles that got into the atmosphere through volcanic eruptions and kept the sun's rays from hitting the earth, similar to the 1815 eruption of the Tambora volcano, which led to the year without a summer in 1816 . A generally reduced solar activity at this time, the Spörminimum , could also come into question. But neither the volcanic eruptions of that time nor the changes in solar activity could explain the cooling in the computer simulations. The analyzes showed that the cooling was much more likely to be caused by an unfavorable random combination of complex natural processes in the interplay of the atmosphere, the oceans and land masses. According to published results, the catastrophe of the 1430s can be explained by random fluctuations in the weather, which resulted in one extremely long winter following the next, interrupted by warm summers with a lot of rain.

See also

literature

- Chantal Camenisch, Kathrin M. Keller, Melanie Salvisberg, Benjamin Amann, Martin Bauch, et al .: The 1430s: a cold period of extraordinary internal climate variability during the early Spörer Minimum with social and economic impacts in north-western and central Europe. In: Climate of the Past . 12, 2016, pp. 2107-2126, doi : 10.5194 / cp-12-2107-2016 .

- Chantal Camenisch: Endless cold: a seasonal reconstruction of temperature and precipitation in the Burgundian Low Countries during the 15th century based on documentary evidence. In: Climate of the Past. 15, 2015, pp. 1049-1066, doi : 10.5194 / cp-11-1049-2015 .

- Chantal Camenisch: Endless cold. Weather conditions and grain prices in the Burgundian Netherlands in the 15th century (= economic, social and environmental history. 5). Schwabe, Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-7965-3468-3 ( doi : 10.24894 / 978-3-7965-3474-4 ; also: Bern, University, dissertation, 2011).

- Christian Jörg: Expensive people, hunger, great dying. Famine and supply crises in the cities of the empire during the 15th century (= monographs on the history of the Middle Ages. 55). Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-7772-0800-8 (At the same time: Trier, University, dissertation, 2006; table of contents ; review ).

- Christian Jörg: "So we should warm up, so come celt." Climate, weather extremes and their relevance for the European famine years around 1438. In: Rolf Kießling , Wolfgang Scheffknecht (Ed.): Environmental history in the region (= Forum Suevicum. 9 ). UVK, Konstanz 2011, ISBN 978-3-86764-321-4 , pp. 111-138.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Chantal Camenisch, et al .: The 1430s: a cold period of extraordinary internal climate variability during the early Spörer Minimum with social and economic impacts in north-western and central Europe. In: Climate of the Past. 12, 2016, pp. 2107-2126.

- ↑ Sven Titz: Climate history: When it was extremely cold in Europe. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung , from December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Axel Bojanowski : Climate catastrophe in the Middle Ages - Europe's toughest decade. In: Spiegel online , December 28, 2016.

- ↑ Chantal Camenisch: Endless cold. Weather conditions and grain prices in the Burgundian Netherlands in the 15th century. 2015.

- ↑ Christian Jörg: Expensive, hungry, great dying. 2008.

- ^ Document of the grain barrier photo series in: Spiegel online

- ↑ Austria Press Agency : The cold 1430s were probably "natural weather variation" In: Science.apa.at of December 2, 2016