Ignition hole

The ignition hole is a small opening in the barrel of a muzzle-loading weapon . It can be on the side or on top of the barrel, e.g. B. guns .

The propellant charge is ignited through the ignition hole with the fuse or the ignition iron . There is also a small indentation at the ignition hole, the so-called pan . On top of it lies the ignition herb used to ignite the charge.

Later guns used propellant bags or cartridges instead of loose powder . After the propellant bag was loaded into the tube, a cartridge needle was pushed through the ignition hole deep into the bag. Then the beater tube or stoppine was driven through the ignition hole into the cartridge.

In guns, the diameter of the ignition hole was 4-6 mm. It was usually perpendicular (90 °) or at a slightly smaller angle of up to 80 ° to the soul axis. The acute angle points backwards. In many cases, the ignition hole is not located right at the edge of the chamber, but is slightly offset to the front. This ensures ignition even if the propellant charge bag has not been pushed all the way down to the chamber floor. Leaning holes had the same purpose. Axial attachment such as B. with the leather cannon .

Until the middle of the 18th century, the ignition hole was drilled directly into the gun barrel. The ignition hole was burnt out a little with every shot, ie widened by the hot and aggressive powder arc. If the pressure loss was too great due to the burned-out ignition hole, the gun became unusable. Of the gun materials used, bronze withstood the process the shortest, cast steel a little longer and cast iron the longest . In the case of pipes made of cast steel and cast iron, however, increasingly cracks appeared, which could lead to the catastrophic bursting of the pipe. Craggy ignition holes also harbored the risk that smoldering powder residues could stick there. Unintentional ignition could occur when loading the next charge.

In Prussia around 1730 attempts were made to close the ignition holes with cast bronze and re-drill them. The new firing holes held only a few shots in comparison. Florent-Jean de Vallière introduced guns to France in 1732 with a core made of forged copper cast into the ignition hole . When the gun was poured, however, the metal around the ignition core cooled too quickly and was therefore more porous. Therefore, in 1774 , the Frenchman Gribeauval developed a threaded ignition hole for bronze guns into which the ignition core was screwed cold. This procedure prevailed for the next few decades.

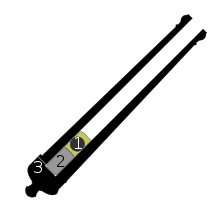

The ignition hole core or ignition hole stud was made of forged copper, was first drilled through and then provided with a thread . The ignition hole core was screwed into the core bearing using a gun screwing machine. The square head served as a screw drive . If the old core was burned out, it was removed and a new one screwed in. As a rule, the old ignition hole core had to be drilled out and the core bearing of the gun had to be supplied with a new thread. The new ignition hole core thus had a larger diameter than the previous one. In the Prussian Army, ignition hole cores with 7 diameter sizes were kept. The screwing again was time-consuming; It took 6 men 10–12 hours. Ignition cores were sometimes used in rifles.

Gold from the lining of the primer hole was also used in luxury handguns. Gold has the advantage that the sulphurous acid does not attack it. The disadvantage of gold is that it has a low melting point , which made it difficult to manufacture the pipe, since the last step in the process of hardening the pipe was to heat it up again. In 1803, gunsmiths in London began using platinum . Platinum has a higher melting point and was cheaper than gold at the time. In the 1860s, some guns were made with ignition cores made of the very tough alloy of platinum / iridium . As this material was very expensive, it was only used in special guns.

In percussion arms which with a percussion cap be ignited in the ignition kernel Zündlochkern as is Piston screwed.

Heavy artillery could not be taken along when escaping quickly because of their weight. In order to make them unusable for the enemy at least temporarily, they were nailed up. To do this, a nail was driven into the ignition hole, which blocked the ignition channel to the main pipe.

Individual evidence

- ^ The perfect Prussian soldier in war and in peace: a paperback for officers and the crew of all weapons , edition 2, Verlag Nauck, 1836 p. 409 [1]

- ↑ a b c d Otto Maresch: Waffenlehre for officers of all weapons. Verlag LW Seidel & Sohn, 1880, p. 230 [2]

- ↑ a b Karl Theodor von Sauer : Plan of the weapon theory , Cotta'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung , 1876 p. 351 [3]

- ↑ John Hodges: A cannon to beat all comers in: New Scientist , February 5, 1987, Volume 113, No. 1546 ISSN 0262-4079 [4]

- ↑ a b c d'Appies, Bluntschli, Bleuler: Use of platinum-iridium as a material for ignition cores of gun tubes in: Zeitschrift für die Schweizerische Artillerie , March 1868, pp. 37–42 [5]

- ↑ a b Handbook for the officers of the royal Prussian artillery Verlag Voss, 1860 p. 215 [6]

- ↑ Alexander I Wilhelmi: Attempt to a Guide for Teaching in Marine Artillery, Volume 3 , Gerold Verlag , 1872, p. 661 [7]

- ↑ Extract from the commission protocols on the experiments carried out in the KK Osterreichische Artillerie since 1820 , 1841, p. 19 [8]

- ↑ Pierer's Universal-Lexikon , Volume 26, 1836, p. 765. [9]

- ↑ Melvyn C. Usselman: Pure Intelligence: The Life of William Hyde Wollaston , University of Chicago Press , 2015, ISBN 9780226245737 , p. 167 [10]

- ↑ Pierer's Universal-Lexikon , Volume 13, 1861, p. 163. [11]