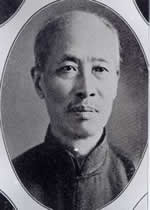

Zheng Xiaoxu

Zheng Xiaoxu ( Chinese 鄭 孝 胥 / 郑 孝 胥 , Pinyin Zhèng Xiàoxū , W.-G. Cheng 4 Hsiao 4 -hsu 1 ; Japanese after Hepburn Tei Kōsho ; * April 2, 1860 in Suzhou , Chinese Empire ; † March 28, 1938 in Xinjing , Manchukuo ) was a Chinese and Manchurian politician, diplomat, and calligrapher, and the first prime minister of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo.

Early life and diplomatic career

The Zheng family's roots were in Minhou near Fuzhou , but Zheng Xiaoxu was born in Suzhou. In 1882 he reached the middle of the Chinese civil service and three years later got a job in Li Hongzhang's secretariat . In 1891 he got a job at the Chinese mission in Tokyo and in the following years took over consular services at the consulates in Tsukiji , Osaka and Kobe . During his time in Kobe, he worked closely with the local Chinese community and helped found a Kongsi , a kind of artisan guild. He also made ties with influential Japanese scholars and politicians such as Itō Hirobumi , Mutsu Munemitsu and Naitō Torajirō .

Government service

After the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, Zheng had to leave Japan and return to China, where he found a job in the secretariat of the reform-oriented politician Zhang Zhidong in Nanking . Zheng later followed him to Beijing when he took up a post at Zongli Yamen , the Qing Foreign Ministry. After the failed Hundred-Day Reform , Zheng left Beijing and took on administrative posts in central and southern China. After the fall of the Qing government in the course of the Xinhai Revolution in late 1911, Zheng remained loyal to the imperial dynasty and refused to serve under the new republican government . He retired into private life and moved into a comfortable house in Shanghai where he turned to calligraphy, poetry and art. In extensive articles he criticized the republican forces, in particular the leadership of the Kuomintang, sharply at this time and described them as thieves.

Qing loyalty and collaboration with Japan

In 1923 the last Qing emperor called Puyi Zheng to Beijing to help him reorganize his imperial household. He became a close advisor to Puyi and helped him escape to the foreign concession in Tianjin after he was evicted from the Forbidden City . Zheng remained loyal to Puyi and established secret contacts with Japanese diplomats and groups such as the Amur Bund . These contacts regularly concerned a restoration of the Qing rule in their home region of Manchuria . After the Mukden incident and the occupation of Manchuria by the Japanese Kwantung Army in 1931, he played an important role in the establishment of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuos in 1932 and became the new state's first prime minister on March 9. Zheng also wrote the lyrics of Manchukuo's first national anthem , Tiandi nai, you le xin Manzhou . Zheng hoped the establishment of a Qing rule in Manchukuo would serve as a stepping stone to reclaim all of China for the Qing, but soon realized that the real masters of the country, the officers of the Kwantung Army, did not share these goals. During his time as Prime Minister there were repeated differences with the Japanese, which is why he resigned from his office in May 1935. He died three years later under unexplained circumstances and received a state funeral in April 1938. He was a member of the Concordia Society, which was increasingly becoming a state party .

heritage

Zheng is remembered mainly for his collaboration with the Japanese, but is also considered an important poet and calligrapher. He is considered one of the most respected and influential Chinese calligraphers of the early 20th century. Already during his lifetime his calligraphy achieved high prices, which allowed him to enjoy a high standard of living. His calligraphy is still known today in China and is used in the logos of various modern Chinese companies.

He kept a comprehensive diary that historians consider to be an important contemporary document.

literature

- Howard L. Boorman, Richard C. Howard, and Joseph KH Cheng (Eds.): Biographical Dictionary of Republican China. Columbia University Press, New York 1967, OCLC 431642652 .

- Jon Eugene von Kowallis: The Subtle Revolution. Poets of the 'Old Schools' during late Qing and early Republican China (= China Research Monographs. 60). Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley 2006, ISBN 1-55729-083-0 .

- Rana Mitter: The Manchurian Myth. Nationalism, Resistance, and Collaboration in Modern China. University of California Press, Berkeley 2000, ISBN 0-520-22111-7 .

- Aisin Gioro Puyi with Lao She : From Emperor to Citizen. The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi. Translated from the Chinese by WJF Jenner. Beijing Foreign Languages Press, Beijing 2002, ISBN 7-119-00772-6 .

- Shin'ichi Yamamuro: Manchuria under Japanese Dominion (= Encounters with Asia. ). University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia 2006, ISBN 0-8122-3912-1 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zheng, Xiaoxu |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 鄭 孝 胥 (Chinese); 郑 孝 胥 (Chinese); Zhèng Xiàoxū (Pinyin Romanization); Cheng4 Hsiao4-hsu1 (Wade-Giles Romanization); Tei Kōsho (Hepburn Romanization) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Chinese and Manchurian politicians |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 2, 1860 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Suzhou (Jiangsu) , Qing Dynasty |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 28, 1938 |

| Place of death | Xinjing , Manchukuo |