Second Vicksburg campaign

| date | March 29, 1863 to July 4, 1863 |

|---|---|

| place | western Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana |

| output | Union victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Major General

Ulysses S. Grant |

Lieutenant General

John C. Pemberton General Joseph E. Johnston |

| Troop strength | |

|

28,800 - 93,565

|

Pemberton: 46,500-29,500

Johnston: 5,900-36,300 |

| losses | |

|

9,300

|

Pemberton: 8,200 + 29,500

Johnston: 2,300 |

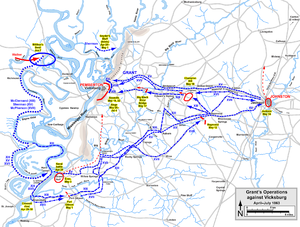

The Second Vicksburg Campaign (March 29 to July 4, 1863) was a military operation during the American Civil War in the western theater of war that took place on both sides of the Mississippi in the states of Mississippi , Arkansas and Louisiana . The goal of the campaign was to conquer the city of Vicksburg , Mississippi , in order to be able to use the Mississippi militarily and economically for the Union without restrictions. The Tennessee Army under Major General Ulysses S. Grant succeeded in taking the city after a series of marches, skirmishes and battles.

prehistory

Abraham Lincoln believed that the fortified city of Vicksburg was the key to victory in the American Civil War. Vicksburg and Port Hudson, Louisiana were the last Confederation bulwarks that prevented the Union from taking complete control of the Mississippi. The city was almost invulnerable to attacks from the river, as Admiral Farragut had found during the failed operations in May 1862 and Major General Grant during the first Vicksburg campaign in the winter of 1862/63.

Although Lincoln continued to put his trust in Grant, he allowed the War Department to send Charles A. Dana, an assistant Secretary of War, to the Tennessee Army as a special envoy to investigate the alleged failure of Grant and allegations of alcohol addiction.

For the Confederation, Vicksburg was the hinge that connected the western parts of the Confederation to the main area. The loss of the city meant not only the loss of secure communications with the west, but also the loss of control of traffic on the Mississippi and the loss of much of the state of Mississippi.

The commanders in chief and commanders

The major players on the Union side were Maj. General Grant, Commander in Chief of the Tennessee Army, and Maj . Generals Sherman, McClernand and McPherson as commanding generals .

- Commander-in-Chief and Commanding Generals of the Union

Major General

William T. ShermanMajor General

John A. McClernandMaj. Gen.

James B. McPherson

The review of the Tennessee Army was extremely satisfactory from both Lincoln and Grant's point of view. Special Envoy Dana praised Grant in his reports as "not a great man but morality" and as "not an original or brilliant person, but an honest, thoughtful and astute man who is endowed with never wavering confidence."

Confederation commanders were General Joseph E. Johnston , Commander West, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton , Commander in Chief of the Mississippi Army and Brigadier General John Stevens Bowen, Pemberton's division commander. The Mississippi Army was specially formed to defend Vicksburg on December 7, 1862. Brigadier General John Gregg led a reinforced brigade of troops directly subordinate to Johnston during the defense of Jackson .

- Supreme Commanders and Commanders of the Confederation

Terrain and operation plan

Vicksburg was situated on a raised plateau at a sharp bend in the river and was called the "Gibraltar of the Mississippi". Ten miles north of Vicksburg on the Yazoo were Confederate fortifications reinforced with artillery on the ridge. South of the city, the highlands continued up to Big Black and Bayou Pierre. The terrain east of Big Black was slightly undulating - the highest peaks were the hills around Champion Hill - the Big Black itself was up to 50 m wide with incised banks. It could only be crossed at crossing points or by boat. To the west followed the heights protruding up to 40 m above the plain, on which Vicksburg was also located.

The area west of the Mississippi in Louisiana intersected countless rivers and former arms of the Mississippi and only a few poor country roads. The weather had changed in early April, causing the Mississippi water level to drop rapidly and ruining all efforts to create navigable canals.

The Tennessee Army was to march south through Louisiana to the level of the mouth of the Big Black. At the same time, the Mississippi squadron was supposed to drive past the fortifications of Vicksburg at night and cross the Tennessee Army across the river, which was about a mile wide. The army's main supply base was to be established on the right bank and secured by gunboats.

After the Mississippi invasion, Grant had three courses of action:

- Attack to the south and capture of Port Hudson, then joint action with Banks on Vicksburg

- First capture of Jackson, then attack on Vicksburg

- Attack to the north and immediate capture of Vicksburg

President and Major General Henry W. Halleck wanted Grant to join Banks in conquering Vicksburg. Halleck once again made this point clear in a telegram dated April 2, but left the decision on how to proceed to Major General Grant - the main thing was the emphasis with which the operations on the Mississippi were pushed.

Grant chose the second option. With Jackson's conquest, he was able to cut off Vicksburg from almost all connection and supply lines. Then the Tennessee Army was to take Vicksburg from the east attacking. When that did not succeed, Grant's troops besieged the city until it surrendered on July 4, 1863. The march through Louisiana and the crossing over the Mississippi was followed by diversionary attacks by the XV. Corps north of Vicksburg and Colonel Grierson's raid . This was to prevent Pemberton from moving troops south.

The campaign

preparation

March through Louisiana

Grant ordered Major General McClernand on March 29, 1863, with the XIII. Corps to march to New Carthage, Louisiana. The XV. and XVII. Corps should follow. McClernand took Richmond, Louisiana - 12 miles from Millikens Bend - on March 31st. During the further march, crossings over bayous had to be made and the poor roads repaired or rebuilt. Because of this, and because of constant fire attacks by Confederate cavalry units, the march lasted until mid-April. These Confederate units were part of Brigadier General Bowens' division, the bulk of which was deployed at Grand Gulf, Mississippi. On April 17, Pemberton gave Bowen permission to withdraw all troops from the west bank.

New Carthage turned out to be unsuitable for the establishment of the army's main supply depot because of the risk of flooding. The new location was set to Hard Times, Louisiana - about 70 miles - the equivalent of three days' march - from Millikens Bend, Louisiana.

Breakthrough of the Mississippi Squadron

Admiral Porter, in consultation with Major General Grant, ordered the Mississippi flotilla on April 16 with eight gunboats and three steamers with twelve barges in tow, and on April 22 with three transport ships manned exclusively by Army volunteers Driving past the fortifications of Vicksburg at night. The steamers were “armored” with water-soaked hay and cotton bales and barrels filled with beef. In addition, barges were attached alongside to prevent hits below the waterline. A transport ship was lost in both actions; two sailors were seriously injured and six were slightly injured. Later on, gunboats and steamers repeatedly managed to steam past Vicksburg at night despite heavy defensive fire.

With the first transport supplies for the supply of the XIII. Corps shipped down the Mississippi, the second was used to increase the transport volume for the Mississippi invasion. Few means of translation were brought to New Carthage via the newly dug Duckport Canal and the various bayous as the water level fell rapidly.

Grierson's raid

Grant had given the commanding general of the XVI. Corps, Major General Hurlbut , ordered a diversionary operation in the Mississippi Army's hinterland to coincide with the Tennessee Army's march south. Hurlbut commissioned Colonel Grierson with a brigade consisting of 1,700 cavalrymen and an artillery battery, the rear connections of the Mississippi Army from Tennessee to the south wherever possible to interrupt and destroy. The raid began on April 17th in La Grange, Tennessee. On April 19, Grierson sent parts of the brigade back to La Grange with prisoners and looted supplies. He hired a regiment to mislead the Confederates about the brigade's intentions through a diversionary maneuver on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad . With the remaining 1,000 men, he rode more than 600 miles through the enemy hinterland, destroyed railroad lines and depots, and reached Baton Rouge , Louisiana on May 2nd .

General Pemberton had little cavalry as Major General Van Dorn was tied up in central Tennessee and Brigadier General Forrest had to fend off Colonel Abel Streights raid in Alabama. The unexpected actions of Grierson led to confused reactions on the part of the Confederate, which is clear from the fact that the army commander-in-chief directed individual regiments. Pemberton tried by all means to fend off the threat to its connection and supply lines. For the protection of the Vicksburg-Jackson railway line, which was vital to the Mississippi Army, he deployed an infantry division that he lacked in defending against Grant after the Mississippi invasion.

Transition attempt at Grand Gulf

Grant ordered the passage at Grand Gulf, Mississippi, to be carried out on April 29 after the gunboats had prepared for fire. Despite five and a half hours of fire fighting, the seven gunboats only managed to turn off the Confederate batteries that were deeper. The gunboats did no damage to the higher ones. The transport ships could therefore not cross over. The gunboat USS Tuscumbia was put out of action during the fire fight. Another attack by the gunboats at night was also unsuccessful, but the transport ships used the tie-up of the Confederate batteries to steam down the Mississippi. Grant moved the XIII. McClernand's Corps on the overland route to Coffee Point, about five miles south of the first planned crossing point.

Lieutenant General Pemberton ordered the troops at Grand Gulf to be reinforced and additional ammunition to be brought there without the defensive efforts north of Vicksburg against Sherman's XV. To neglect Corps and without weakening the units deployed to defend against Grierson's raid.

Attack at Snyders Mill

Admiral Porter had parts of the Mississippi flotilla on April 27 to work with Sherman's XV. Corps instructed. Grant did not intend to undertake a large-scale diversion north of Vicksburg, because he feared for the morale of the soldiers and the public lack of understanding for such an undertaking. He therefore left the decision to Sherman to deploy a diversionary maneuver. Grant merely ordered that if it was carried out it would have to be coordinated with the Mississippi landing. Sherman decided on a diversionary operation that could eventually be turned into an attack. He carried out the diversionary maneuver with ten regiments and with fire support from gunboats on April 30 and May 1. The Confederates did not recognize the deception as such and therefore could not move as many troops south as they could have.

Crossing at Bruinsburg

After the failed transition attempt at Grand Gulf and after Grant had received information about a good route from a landing site at Bruinsburg, Mississippi to Port Gibson, Mississippi, he ordered the transition across the river to be carried out on April 30 and May 1. The XIII. Corps forced the Mississippi at dawn on April 30th without interference from Confederate troops, the XVII. Corps followed immediately. To secure the bridgehead, the soldiers of the XIII. Corps fed for three days and marched off towards Port Gibson. The landing site itself was protected by the gunboats.

The landing had not gone unnoticed by the Confederates. Brigadier General Bowen reported the arrival of the XIII at 3:00 p.m. on April 30. Corps in the direction of Port Gibson and that more troops were landed. Lt. Gen. Pemberton reported to President Jefferson Davis a day later that he urgently needed reinforcements from other areas of the defense because the entire Tennessee Army could cross the river and the character of the defense of Vicksburg had changed.

Confederate reactions

The Grant's diversionary measures had worked. Although Pemberton knew by April 17 at the latest that the Tennessee Army had marched south with a large part of its forces and that the breakthrough of the Mississippi flotilla had not gone unnoticed, he fell again into the mistake of many high-ranking southerners to defend everything want. Pemberton ordered formations in Vicksburg and northern Mississippi on April 28 and 29 to prepare for marching readiness, but sent only small reinforcements to Grand Gulf. Johnston, headquartered in Tullahoma, Tennessee, on May 1, instructed Pemberton on the same day to regroup all of his forces and beat Grant upon landing in Mississippi. Johnston repeated this order the next day, stating that success was worth the risk. Pemberton tried to comply with this instruction and on May 1st ordered a large number of troops to assemble in Jackson or Vicksburg in order to then proceed against the landed parts of the Tennessee Army. At the same time he left units of regimental strength in all other hot spots in Mississippi. When President Davis urged Pemberton on May 7 to hold Vicksburg and Port Hudson, the latter broke off these efforts and concentrated on defending Vicksburg. Johnston himself did not intervene immediately for three reasons:

- He was about 500 miles from the scene.

- Immediately at this point in time, he had no troops under his control.

- Grant's attack took place in the defined area of Pemberton's command, which was responsible not only for Vicksburg, but for all of Mississippi and northeastern Louisiana. The direct intervention of the next higher troop leader only made sense when he was there and could assess the situation there.

Approach to the northeast

Port Gibson

About four miles southwest of Port Gibson met the XIII. Corps to Bowen's first units. Major General McClernand attacked immediately and, having received reinforcements from McPherson's Corps, succeeded in forcing the Confederates to evade to Grand Gulf. The Confederates destroyed the bridges over Bayou Pierre, which were quickly restored by Union forces. The Tennessee Army's bridgehead was secured.

Raymond

The Tennessee Army's supply base was on the west bank of the Mississippi. Grant therefore ordered that the regiments' supply columns should not cross over to the eastern bank until all combat units had crossed over. Transporting ammunition had absolute priority and so the Tennessee Army requisitioned anything that could transport ammunition on the east bank. For the march to Jackson, Grant ordered the army to feed on the land. This led to this bizarre incident: a farmer complained to a division commander that the soldiers had stolen everything he owned. He rode a mule. The division commander replied: If they had been soldiers from his division, he would no longer be sitting on the mule.

General Pemberton expected that the Tennessee Army would attack Vicksburg from the south over the Big Black after the victory at Port Gibson. He therefore deployed 20,000 men at the crossings of the Big Black and left 10,000 men as crew and reserves in Vicksburg. At the same time he ordered Brigadier General Gregg with a brigade from Port Hudson, Louisiana to Raymond. There Gregg was supposed to prepare to attack the Tennessee Army advancing on Vicksburg in the rear. However, should the enemy be superior, Lieutenant General Pemberton ordered the evacuation to Jackson. Gregg reached Raymond unnoticed by Union troops on the afternoon of May 11th.

After the success at Port Gibson, the two corps of the Tennessee Army marched northeast on two streets. The XV. Shermans Corps had meanwhile crossed the Mississippi at Bruinsburg and followed. Because of the Pemberton's assessment of the situation on May 11th, Gregg assessed the foremost parts of the XVII. Corps McPhersons as a marauding brigade and attacked the approximately 10,000-strong corps at Raymond on May 12 with 2,500 men . After initial success, the Union soldiers fended off the attack. To avoid total annihilation, Gregg evaded Jackson.

Jackson

Secretary of War Seddon had ordered General Johnston on May 9th to personally take the lead in Mississippi. After a four-day train ride, Johnston, who was still disabled due to illness, reached Jackson on May 13th. That same evening he ordered Pemberton to attack Union forces on the Vicksburg-Jackson railroad and to unite with him north of Clinton, Mississippi.

Johnston had the Greggs and Walkers Brigades in Jackson, about 6,000 men in all; Reinforcements from other parts of the Confederation were on their way. Johnston realized that he was unable to hold Jackson with his strength and evacuated as much people and material as he could.

After five hours, Johnston broke off the engagement and dodged north on the Canton, Mississippi road. From there he intended to march southwest and unite with Pemberton. The XV. Major General Sherman's Corps occupied Jackson and burned the city to the ground. The occupiers then named the city "Chimneyville". The railway lines were permanently destroyed in all directions; Pemberton's Mississippi Army was cut off from reinforcements and supplies.

Attack on Vicksburg

Champion Hill

In the meantime, McClernand's and McPherson's corps had turned west and were preparing to attack Vicksburg.

Pemberton reported to Davis on May 12th that he wanted to beat the opponent at Edward's station . To do this, he intended to carry out a raid against the lines of the Tennessee Army between Raymond and Port Gibson with two divisions, and to get Grant to then pursue him and attack at Edwards Station. On May 14th, he marched south with 17,000 men. After the march began, Pemberton was commissioned by Johnstons, the XV. Tennessee Army Corps on the Vicksburg - Jackson Railway Line. Reluctantly, he carried it out and marched north. The Mississippi Army occupied the positions on Champion Hill with three divisions.

The XIII. Corps proceeded cautiously in the south against the positions of the southerners on May 16, as ordered. After the Confederate positions had been clearly identified, Grant asked McClernand several times to accelerate his approach without any change in the behavior of the troops of the XIII. Corps to achieve. Therefore, the burden of the attack in the north was on the XVII. McPherson Corps attacking Pemberton's left flank. A counterattack by Brigadier General Bowens' division remained after initial success. In order to avoid an overflank in the north, Pemberton had to give up the good positions and move in the direction of Vicksburg. The soldiers of the Mississippi Army were demoralized by the senseless marching movements and the fighting, so that avoiding them was sometimes equivalent to fleeing.

Major General Loring, division commander of the right-wing division, carried out Pemberton's orders so idiosyncratically that contact with the other two divisions of the Mississippi Army was lost. Loring dodged south, then turned north.

On May 16, General Johnston's troops, which had meanwhile increased to around 11,000 men and were later reinforced by Loring's division, were near Cantons. The defeat at Champion Hill and the evasion in the direction of Vicksburg made a union of the two armed forces of Pembertons and Johnstons north of the railway line and a joint attack against the Tennessee Army obsolete.

Defense on Big Black

Pemberton definitely wanted to use Loring's division to defend Vicksburg. He therefore ordered Brigadier General Bowen to hold the railway bridge over the Big Black until Loring's division had evaded it. The XIII. McClernand's Corps attacked Confederate forces head-on at the bridge on May 17. The Union troops were vastly superior. After the first exchanges of fire between the local security forces, the Confederates left their positions and fled to Vicksburg without any serious defense efforts. Loring's division united with Johnston's troops north of Jackson.

Attacks against Vicksburg

The remaining parts of the Mississippi Army, about 20,000 men, assembled at Vicksburg and set up on the heights for defense. General Grant believed, spurred on by the successes of the Tennessee Army, he could take the city in one last rush. He scheduled the start of the attack at 2:00 p.m. on May 19. However, only the XV. Shermans Corps because it was the only corps to have reached the storm starting positions. The city's defenders repelled the attack.

Johnston was then in Canton, Mississippi, about 50 miles northeast of Vicksburg. It was reinforced daily. Grant wanted to keep Johnston from interfering with Vicksburg. Therefore, after all three corps had been assembled, he ordered another attack on the positions of the southerners on May 22nd. After taking Vicksburg, he wanted to turn east and beat Johnston. The Mississippi Army fended off the attack with great losses for the Tennessee Army. Grant later said of the attack that he regretted ordering it. The Tennessee Army lost 4,141 soldiers.

Siege of Vicksburg and relief attacks

The siege of Vicksburg lasted from May 22nd to July 4th. The Tennessee Army tried with the means available at the time, such as undermining the positions, artillery bombardment from land and by gunboats from the Mississippi and the Yazoo, and repeated attacks on individual Confederate positions, to break into the defense. All attempts by the Tennessee Army to take Vicksburg failed. It was only when the Confederate troops and residents of Vicksburg were starving to death that Lieutenant General Pemberton Grant offered to surrender on July 3. Major General Grant initially insisted on unconditional surrender, later reconsidered and allowed the Mississippi Army to be released on parole . Even if this seemed to run diametrically against his principles, this 'human' decision arose from a very simple rational consideration - how should he feed more than 20,000 prisoners of war or transport them to the north? It was much easier to leave them to their own devices, even if they should then fight again in one of the Confederate armies. During the siege, the Tennessee Army mourned 111 fallen or missing soldiers and over 400 wounded, but almost all of them recovered during the siege. The losses of the Confederates amounted to 2,872 soldiers by the surrender.

Millikens Bend

As early as May 1st, Lieutenant General Pemberton asked the commander of the Trans-Mississippi Defense Area, Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith , to relieve him by attacking the bases and troops of the Tennessee Army on the right bank of the Mississippi. This invitation was repeated by Pemberton on May 9th and Johnston on May 15th. Even the War Department asked Smith to exonerate Vicksburg.

In early June, Smith commissioned a reinforced division under Maj. General Taylor to destroy the Tennessee Army's supply bases on the right bank of the Mississippi. The Confederates had missed the fact that Grant had moved the supply bases north of Vicksburg to the east bank. The facilities that still existed at Richmond and Millikens Bend were protected by African American regiments made up of freed former slaves. They were poorly trained and poorly equipped.

On June 6th, Confederate troops had taken Richmond and were detected by Northerners forcibly. On June 7th, the Southerners attacked the Northerners at Millikens Bend, Grant's headquarters during the first Vicksburg campaign. When two gunboats intervened in the battle, the Confederates had to stop their attack. Grant wrote in his report that the African American Union soldiers fought very bravely and with dedication.

Captured colored people posed a particular problem. The southern commanders did not know how to treat them. Reports that evasive Confederate units had killed colored soldiers who surrendered beforehand were untrue, according to eyewitnesses. However, some of the prisoners of war were sold as slaves again.

Goodrich's Landing

After conquering the counties in northeastern Louisiana, the Union troops had begun to cultivate agricultural produce with the freed slaves on the leased land. To get troops free for the siege of Vicksburg, Grant had entrusted African-American troops with securing the area west of the Mississippi. The Confederates wanted above all to stop the use of the former slaves and at the same time destroy supply facilities of the Tennessee Army. On June 29, they and a cavalry brigade captured a fort in the Lake Providence, Louisiana area, about 50 miles northwest of Vicksburg up the Mississippi, without a fight. The Confederates then burned and destroyed the surrounding plantations and fields.

The Mississippi Flotilla landed at dawn on June 30, the Mississippi Marines Brigade and some African-American units. The Confederates had to evade after fierce fighting and broke off the fight in the evening.

Despite the considerable destruction by the Confederates, the Union suffered no lasting damage. The Union troops also had no problems with replacing large quantities of booty.

Helena

General Johnston asked Lieutenant General Smith to take offensive action against Port Hudson on May 31, and Helena, Arkansas on June 3. The small town of Helena was an important Union base on the right bank of the Mississippi and had a crew of 20,000 men. At the beginning of July Grant had ordered 16,000 soldiers from the city to reinforce the siege ring in Vicksburg. A crew of about 4,000 men and the wood-clad gunboat USS Tyler remained in Helena.

Lieutenant General Theophilus H. Holmes , commander of the Confederate Defense District of Arkansas, decided in late June to relieve the Mississippi Army trapped in Vicksburg. On July 4, Holmes attacked Helena from three sides with 6,000 men. The attack was characterized by poor coordination. Even so, the Confederates managed to take the hills surrounding the city. Holmes, unable to decide how to proceed with the attack, gave conflicting and confusing orders, and the Confederate advantage was given away in the increasingly violent Union defensive fire. Holmes realized that the situation was changing to the disadvantage of the Confederates and broke off the attack around 10:30.

Pursuit of Johnston East

On May 18, the Mississippi Army gave up the key site at Haynes Bluff , which had been bitterly fought over at the turn of the year. The Tennessee Army could now use the Mississippi and Yazoo to transport soldiers for reinforcement in front of Vicksburg and for supplies without being able to be disturbed by Confederates or geography. Grant moved all utilities from the west bank of the Mississippi to the Yazoo near Haynes Bluff. With the reinforcements, the Tennessee Army secured itself from there to the southeast as far as the Big Black in order to be prepared against an attack by Johnston. At the end of the siege, about 70,000 Union soldiers were gathered at Vicksburg, about half of whom were used for the siege and to repel a possible attack from the east. The focus of the defense to the east was the key area at Haynes Bluff, which Grant had fortified and occupied with 13,000 men.

After Vicksburg's surrender, the campaign was not over. In the rear of the Tennessee Army were Johnston's units, which had grown to 28,000 men by June 25. He had not intervened during the siege because it was clear to him that he could not attack the Tennessee Army with any prospect of success. On the other hand, Grant could not allow such a large, if clearly inferior, Confederate force to reside in his hinterland. Grant commissioned Sherman on July 4th with three corps, approximately 55,000 men, to attack Johnston, who had increased his troop strength to approximately 31,000 men, and to drive him out of the western Mississippi.

The Confederate units were pursued eastwards after fighting on the Big Black. Johnston intended to lure Sherman into an attack on his troops dug into Jackson. Sherman did not attack, however, possibly in memory of the unsuccessful attacks on Vicksburg on May 19 and 22, but prepared to besiege Jackson. To save the troops, the Confederates gave up Jackson again on July 16 and dodged behind the Pearl. Grant's goal of being able to use the Mississippi as far as Vicksburg for the Union without threat was achieved.

Personal details and strategic assessment

Replacement of McClernand

Major General McClernand was a political general and fellow party member of Lincoln. Grant released McClernand from leading the campaign during the first Vicksburg campaign. Even before that, there were always differences between the two generals, especially because McClernand repeatedly described himself in public as more far-sighted and better suited to leading the Tennessee Army. This face-to-face public relations was not uncommon during the Civil War - McClellan and Hooker were two examples.

Grant's reluctance was heightened by McClernand's disobedience during the campaign. For example, the embarkation of the XIII was delayed. Corps by half a day because McClernand had his bride and her belongings shipped, even though Grant had forbidden all officers to ship any personal effects.

During the second attack on Vicksburg on May 22nd, McClernand reported that he had already captured two Confederate forts and that he now needed support from McPherson forces. Indeed, McClernand's troops were insufficient to break into Confederate positions. He wanted to force the break-in with additional troops and have the success credited personally to him. Special Envoy Charles A. Dana reported War Secretary Stanton on May 24 that Grant had toyed with the idea of replacing McClernand because of this action. Grant only wanted to believe McClernand's reports if they had been confirmed by others. Dana himself found McClernand absolutely unsuitable, he even denied him any ability to lead a regiment.

McClernand issued an order on May 30, in which he gave the members of the XIII. Corps thanked for the performance shown. He sent this order to the press against Grant's express order. On June 17, McPherson and Sherman complained to Grant about press coverage that the Tennessee Army's successes were exclusive to the XIII. Attributed to Corps and McClernand. Major General Grant relieved McClernand of command on June 18, replacing Major General OC Ord . McClernand pointed out in his reply that he had been installed by the president, but he complied with the order.

Confederate commanders

The two Confederate generals played a major role in the defeat at Vicksburg. Both are accused of wrong and hesitant behavior, with the critics assigning the one more and the other less responsibility for the defeat, and vice versa.

Pemberton was from the north and had entered the Confederation for the sake of his wife. He was a favorite of President Davis and was allowed to report to the President without notifying his commander. At the same time he received direct instructions from the President.

Johnston, a short, impeccably dressed, ambitious man with penetrating eyes and a great sense of reputation, believed that the Confederation could win the war if it only lost it. His relationship with the President was marked by Johnston's aversion to the Richmond politicians, whose goal in his eyes was to defend everything with far too little strength. Davis saw in Johnston a loner who put obstacles in his way because Johnston was friends with an opponent of Davis' in the Senate. Because of Johnston's excellent skills as a leader, Davis was forced to use him in a responsible position.

- Pemberton

On May 1st, Lieutenant General Pemberton ordered individual regiments from many large formations in his command area to support Brigadier General Bowen at Grand Gulf and inevitably led them personally. He reported to President Davis on May 2 that nearly all of the enemy’s troops had landed in Mississippi and that he was concentrating all the forces he could use - not all he had - north of the Big Black. That was about 3,500 men compared to a total strength of the available troops of about 20,000 soldiers. Probably in response to General Johnston's instruction to hit the enemy with everything he had at his disposal, he ordered all troops from the north to Vicksburg beginning on May 2 and reported to the President that he would manage to deal with the situation. The difficulties in returning the individual regiments to their large formations were so great that Pemberton stayed with his staff on May 3 to create order. On the morning of May 5th, all units were with their respective brigades and divisions. In the days that followed, Pemberton built a line of defense from Warrenton, Mississippi, ten miles south of Vicksburg, along the Big Black to north Edwards Station on the Southern Railroad and on to Haynes Bluff. On May 7, he ordered all of Jackson's utilities to be evacuated to the east because he expected a raid on Jackson and a simultaneous attack on the railway bridge over the Big Black. Pemberton, who had meanwhile been ordered by the President to hold Vicksburg and Port Hudson at all costs, ordered parts of the reinforcements already on the march from Port Hudson. After the defeats at Champion Hill and at the railway bridge over the Big Black and the victorious defense against Grant's attacks on Vicksburg, Pemberton informed Johnston on May 29 about the situation. He pointed out that he advised against attempting relief with fewer than 30 or 35,000 men. In the further course of communication with Johnston, Pemberton repeatedly demanded an attempt at relief and reinforcements for Vicksburg. It was not until June 21, after constant demands by Johnston, that Pemberton proposed a joint plan of operations.

- Johnston

Johnston's instruction to Pemberton on May 2nd to attack the Tennessee Army with all its might and at the greatest risk contained nothing more than a military truism, but it was apparently necessary since Pemberton did not begin to muster all forces until May 3rd. On May 8, Johnston expressed satisfaction with the division of the Mississippi Army, which could so quickly be concentrated against Grant's army.

Johnston only wanted to attack the enemy if he was clearly superior to him. Since the Confederates were almost exclusively outnumbered in the West, he always tried to compensate for the inferiority by skillfully selecting the terrain. When Pemberton announced on May 17 that he had ordered the abandonment of Snyder's Bluff, Johnston saw the abandonment of the key site for the defense of Vicksburg: The following siege of the city would end with the loss of Vicksburg and the enclosed Mississippi Army. He therefore ordered Pemberton to break out to the northeast for the first time on the same day, if it was not already too late.

Johnston kept Pemberton informed of his efforts to appall him. Johnston's troops had grown to about 15,000 men by the end of May. An attack to Vicksburg was ruled out for him, however, since Grant's troops, which were used exclusively to repel such an attack, were initially equally strong, later even superior. Johnston asked Pemberton for the first time on May 29th to meet him. On June 21, Pemberton responded to his repetitive demands for a joint plan of operations. Johnston promised Pemberton on June 22nd that he would compete in two to three days, even if his strength was only two-thirds of the minimum strength proposed by Pemberton. In fact, on July 3rd, Johnston announced to Pemberton that he would attack on July 7th. The first movements started the same day and reached the Big Black on July 4th. The aim of this attack was solely to save the combat-strong parts - around 20,000 men - of the garrison. After the surrender, further action against a superior opponent was pointless and Johnston avoided fighting on positions at Jackson.

Strategic evaluation

Major General Grant had decided to cross the Mississippi south of Vicksburg after the failures during the first Vicksburg campaign against the advice of Generals Sherman and McPherson. After crossing the Mississippi, he had left all alternatives open. His favored planning was to seal off relief attacks for Vicksburg from the east and take Vicksburg with the Tennessee Army. Grant was right that Banks was unable to follow his own pace - if both armies had acted together, as the President would have liked, he would have been the junior and Banks would have been in command of the campaign.

The Tennessee Army marched more than 180 miles in 17 days, supported by the successful diversionary maneuvers Griersons and Sherman, and fought and won five skirmishes and battles against individual sections of the Mississippi Army. Merging the Confederate troops would have brought Pemberton and later Johnston to roughly the same strength as the Union. With his own casualties of 4,300 dead, wounded and missing, Grant inflicted losses on the Confederate 7,200 soldiers.

Johnston had asked the President in 1862 to decide which state - Tennessee or Mississippi - to hold. Since the forces were too small to defend both states, no soldier could make this decision. Jefferson Davis also rejected Johnston's proposal to subordinate parts of the more than 50,000-strong army west of the Mississippi to Pemberton and thus first defeat Grant and then retake Missouri.

General Lee's categorical refusal to surrender troops from the eastern theater of war to reinforce the Mississippi Army, and General Beauregard's hesitant resignation of troops, show that a possible loss of Vicksburg was not considered to be so decisive compared to the other projects. Davis' constant promises to Pemberton that he would send reinforcements were counterproductive to Johnston's efforts to at least save the garrison, because they led Pemberton to believe that the city was up for grabs. The accusation against Johnston that an earlier attempt at relief, even with strongly inferior forces, would have saved Vicksburg, is purely speculative. According to the prevailing military teaching of Jomini , Johnston did the right thing. Certainly there were many mistakes local commanders made that collectively led to the fall of Vicksburg, but one of the biggest mistakes was the belief by Confederate leaders that the Mississippi would be closed to the Union by holding some fortified sites can. As a result, the crews of these fortified places were inferior to the Tennessee Army and were easy to defeat by siege operations. Another decisive factor in the Confederate defeat was the Commander-in-Chief of the Tennessee Army - who surpassed his opponent Johnston in leadership.

Despite the supposed importance of Vicksburg as the hinge of the Confederation, the Confederation did not fall apart after the fall of Vicksburg. After the Vicksburg campaign, the Confederation had lost half of Mississippi, and significant agricultural land was no longer used to supply the population. There was no connection with the defeat of the Confederates at Gettysburg . In the opinion of many historians, the successful conclusion of the second Vicksburg campaign was the Union's most important strategic victory, less militarily than psychologically. Even if peace had been made, the confederation would have been a divided country. And with Lee's defeat at Gettysburg the day before, the Confederation had suffered a moral blow. With the defeat it was clear that the hope of recognition of the confederation by European states had been given the coup de grace.

Militarily, the victory was meaningless - the victors were on the remote periphery with no worthwhile targets within reach. While the Confederate losses were substantial, they were not critical. Many of the sacked southerners later fought again at Chattanooga against the same soldiers of the Tennessee Army as before Vicksburg. In addition, the permanent interruption of communication and trade across the Mississippi was not feasible. For Major General Grant, Vicksburg was the springboard for his career as Commander in Chief of the US Army in 1864 and led to the relocation of the focus to the eastern theater of war.

The national holiday on which the surrender fell was not celebrated again in Vicksburg until 1944. On July 8, Banks finally succeeded in taking Port Hudson, the last remaining base of the Confederation on the Mississippi. Only then was control of the Mississippi complete and the strategic benefit of the victory at Vicksburg secured.

Film adaptations

- The Last Command (1959)

literature

- United States. War Dept .: The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies . Govt. Print. Off., Washington 1880-1901.

- Ulysses Simpson Grant: Personal Memoirs of US Grant . New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86, ISBN 1-58734-091-7 ( Online Edition: Published April 2000 )

- Robert Underwood Johnson, Clarence Clough Buell: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War . New York 1887.

- Bernd G. Längin : The American Civil War - A chronicle in pictures day by day . Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1998, ISBN 3-86047-900-8 .

- James M. McPherson : Battle Cry of Freedom . Oxford University Press, New York 2003, ISBN 0-19-516895-X .

- James M. McPherson (Editor): The Atlas of the Civil War . Philadelphia 2005, ISBN 0-7624-2356-0

- Bearss, Edwin Cole: The Campaign for Vicksburg . 3 Vols. Dayton, OH 1985-86.

- Ballard, Michael B .: Vicksburg: The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi . Chapel Hill, NC 2005.

- Dr. Christopher R. Gabel: Battle Command Incompetencies: John C. Pemberton in the Vicksburg Campaign . Studies in Battle Command, Combat Studies Institute, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. here online

- Dr. Christopher R. Gabel: Staff Ride Handbook for the Vicksburg Campaign . Combat Studies Institute, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2001 online here

Web links

- The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies

- Vicksburg National Military Park

- Animation of both campaigns

References and comments

- ↑ a b Dr. Christopher R. Gabel: Staff Ride Handbook for The Vicksburg Campaign December 1862 - July 1863, chap. II p. 11. Combat Studies Institute US Army Command and General Staff College, June 2001, accessed September 22, 2014 . average strengths during the campaign

- ↑ a b Dr. Christopher R. Gabel: Staff Ride Handbook for The Vicksburg Campaign December 1862 - July 1863, chap. II p. 11. Combat Studies Institute US Army Command and General Staff College, June 2001, accessed September 22, 2014 (29,500 soldiers have surrendered). average casualties during the campaign

- ↑ The naming is analogous to the classification of the National Park Service Operations Against Vicksburg

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 590

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 25: Use your own judgment

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, pp. 46f: March through Louisiana

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, pp. 139f: March through Louisiana

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 755: Dodging to the east bank

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 75: 1st breakthrough at Vicksburg

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 78: 2nd breakthrough at Vicksburg

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 521ff: Reports Griersons

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, pp. 781-802: Pemberton's Reactions

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 48: Grant's report

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, pp. 803ff: Reinforcements for Grand Gulf

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 240: Commissioned by Sherman

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 658: Advance Detected

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 807: Request for reinforcements

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 752: Grant is in New Carthage

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 800: Prepare to march

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, pp. 803/805: Prepare to march

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 808: Attack Grant immediately

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 815: Success is worth the risk

- ↑ Greg Goebel, The American Civil War: You wouldn't have the mule either! Also in James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 629

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 855f: Depending on the situation: attack or evade

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, pp. 737f: Greggs report on the battle at Raymond

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 215: Personally Take Over

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 870: Attack to the North

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 787: Duration and intensity of the battle

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 630

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 859: There is the battlefield

- ↑ Personal Memoirs of US Grant, chap. 35, section 27ff: Operation plan

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 267: You have failed your duty.

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 54: The opponent is demoralized

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 329: Attack order for May 19

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 333f: attack order for May 22nd

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part II, p. 167: Losses During the Attacks

- ↑ When Fort Donelson surrendered in 1862, Grant had insisted on unconditional surrender. According to his initials - US = Unconditional Surrender - this became his nickname

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 636

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part II, p. 328: Confederate losses during the siege

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 808: Request to Smith

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part II, p. 459: Treatment of Prisoners

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 998: Johnston to Smith

- ↑ Dr. Christopher R. Gabel: Staff Ride Handbook for The Vicksburg Campaign December 1862 - July 1863, chap. II p. 79. Combat Studies Institute US Army Command and General Staff College, June 2001, accessed March 27, 2018 . Key site

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, pp. 42f: Attachment of Haynes Bluff

- ↑ According to the classification of the NPS, Sherman's attack on Johnston's Confederate troops is not part of the campaign

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 978: Strength of Johnston on June 25th

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, pp. 80f: McClernand's Bride

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Dana: Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 27: Two forts taken

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 87: McClernand is incompetent

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, pp. 159ff: Congratulations

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, pp. 163f Complaint

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part I, p. 103: Detachment

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 336

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, P. 809ff: Individual commands

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 814: I draw forces together

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 817: Gathering in Vicksburg

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 821: Mr. President, I can do it

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 824: The OB brings order to the staff

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 842: Defense Positions

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 929f: Relief only with sufficient strength

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 969: Plan of Operations

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 844: agree to the division of troops

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 887: Snyder's Bluff is abandoned

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 888: immediate outbreak

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 929: Joint Operation

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XXIV, Part III, p. 971: I'm attacking soon

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 631

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 637

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 664

- ↑ Dr. Christopher R. Gabel: Evaluation. Combat Studies Institute US Army Command and General Staff College, June 2001, accessed January 25, 2016 (pp. 81 ff).