Trent Edwards and Prime number: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

m Reverted edits by 76.64.63.133 to last version by Soliloquial (HG) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Divisor classes}} |

|||

{{Infobox NFLactive |

|||

In [[mathematics]], a '''prime number''' (or a '''prime''') is a [[natural number]] which has exactly two '''distinct''' natural number [[divisor]]s: [[1 (number)|1]] and itself. An infinitude of prime numbers exists, as demonstrated by [[Euclid]] around 300 BC. The first twenty-five prime numbers are:<!--Do not add 1 to this list. Its exclusion from the list is addressed in the “History of prime numbers” section below.--> |

|||

|currentteam=Buffalo Bills |

|||

:[[2 (number)|2]], [[3 (number)|3]], [[5 (number)|5]], [[7 (number)|7]], [[11 (number)|11]], [[13 (number)|13]], [[17 (number)|17]], [[19 (number)|19]], [[23 (number)|23]], [[29 (number)|29]], [[31 (number)|31]], [[37 (number)|37]], [[41 (number)|41]], [[43 (number)|43]], [[47 (number)|47]], [[53 (number)|53]], [[59 (number)|59]], [[61 (number)|61]], [[67 (number)|67]], [[71 (number)|71]], [[73 (number)|73]], [[79 (number)|79]], [[83 (number)|83]], [[89 (number)|89]], [[97 (number)|97]] {{OEIS|id=A000040}}. |

|||

|image=Trent_Edwards_10_28_2007.jpg |

|||

See the [[list of prime numbers]] for a longer list. The number ''one'' is by definition not a prime number; see the discussion below under ''[[#Primality of one|Primality of one]]''. The [[Set (mathematics)|set]] of prime numbers is sometimes denoted by ℙ. |

|||

|width=200 |

|||

|caption=Trent Edwards in action against the New York Jets in 2007. |

|||

|currentnumber=5 |

|||

|currentposition=Quarterback |

|||

|birthdate={{birth date and age|1983|10|30}} |

|||

|birthplace=Los Gatos, California |

|||

|heightft=6 |

|||

|heightin=4 |

|||

|weight=231 |

|||

|debutyear=2007 |

|||

|debutteam=Buffalo Bills |

|||

|highlights=<nowiki></nowiki> |

|||

* ''[[Sporting News]]'' Freshman All-[[Pacific Ten Conference|Pac-10]] (2003) |

|||

* Stanford Cardinal Team MVP (2005) |

|||

* NFL All-Rookie Team (2007) |

|||

* [[San Jose Mercury News]] South Bay Sports POY (2007) |

|||

|college=[[Stanford Cardinal football|Stanford]] |

|||

|draftyear=2007 |

|||

|draftround=3 |

|||

|draftpick=92 |

|||

|pastteams=<nowiki></nowiki> |

|||

* [[Buffalo Bills]] (2007-present) |

|||

|statweek=4 |

|||

|statseason=2008 |

|||

|statlabel1=[[Touchdown|TD]]-[[Interception (football)|INT]] |

|||

|statvalue1=11-10 |

|||

|statlabel2=Passing yards |

|||

|statvalue2=2,560 |

|||

|statlabel3=[[Passer rating|QB Rating]] |

|||

|statvalue3=77.5 |

|||

|nfl=EDW720778 |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Trent Edwards''' (born [[October 30]], [[1983]], in [[Los Gatos, California]]) is a professional [[American football]] [[quarterback]] for the [[Buffalo Bills]] of the [[National Football League]]. He was drafted by the Bills in the third round of the [[2007 NFL Draft]]. He played [[college football]] at [[Stanford Cardinal football|Stanford]]. |

|||

The property of being a prime is called '''primality''', and the word '''prime''' is also used as an adjective. Since two is the only even prime number, the term '''odd prime''' refers to any prime number greater than two. |

|||

==High school career== |

|||

Edwards was a highly-rated recruit from [[Los Gatos High School]] and was ranked as the #1 pro-style quarterback by ''[[USA Today]]'' in 2001.<ref name="USAToday">{{cite web| last =Emfinger| first =Max| title =A midsummer look: A dandy dozen quarterbacks |

|||

| work =USA Today |

|||

| date =July 18, 2001 |

|||

| url =http://www.usatoday.com/sports/college/football/recruiting/2001-07-17-maxcol.htm |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-31 }}</ref> Rivals rated Edwards as the #2 pro-style quarterback and #20 player overall in its rankings. <ref>[http://rivals100.rivals.com/viewprospect.asp?Sport=1&pr_key=1949 Trent Edwards Profile - Football Recruiting<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> He was recruited by [[Michigan]], [[Florida]], [[Notre Dame]] and [[Tennessee]], but ultimately chose [[Stanford]]. In his junior and senior seasons at Los Gatos, he led the team to two undefeated seasons and back-to-back [[Central Coast Section]] Division III championships. In his senior year, he completed 154 of 213 passes for 2,535 yards, 29 touchdowns, and just three interceptions. |

|||

The study of prime numbers is part of [[number theory]], the branch of mathematics which encompasses the study of natural numbers. Prime numbers have been the subject of intense research, yet some fundamental questions, such as the [[Riemann hypothesis]] and the [[Goldbach's conjecture|Goldbach conjecture]], have been unresolved for more than a century. The problem of modelling the distribution of prime numbers is a popular subject of investigation for number theorists: when looking at individual numbers, the primes seem to be randomly distributed, but the “global” distribution of primes follows well-defined laws. |

|||

==College career== |

|||

At Stanford, Edwards sat out his freshman year in 2002, and began 2003 behind starter [[Chris Lewis (quarterback)|Chris Lewis]]. After an impressive showing as a back up, Edwards got the start for four games, but was then sidelined with a shoulder injury for the rest of the season. In 2004, Edwards was the starter, but again suffered injuries that knocked him out of two games and kept him out of two others entirely. Edwards' best year was 2005, where he started all 11 games, completed 168 of 268 passes for 1934 yards and 17 touchdowns, leading the Cardinal to a 5-6 record.<ref name="mediaguide06">{{cite web| title =Player Bio: Trent Edwards |

|||

| work =Stanford Football Media Guide |

|||

| date =2006 |

|||

| url =http://graphics.fansonly.com/photos/schools/stan/sports/m-footbl/auto_pdf/2006_Football_Media_Gd_37-100.pdf |

|||

| pages =pp. 56-57 |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-31 }}</ref> |

|||

The notion of prime number has been generalized in many different branches of mathematics. |

|||

In 2006, Edwards was the starter for the first seven games, but suffered a season-ending broken foot against [[University of Arizona|Arizona]] and relinquished the starting role to [[T. C. Ostrander]]. Despite Stanford's poor performance during his tenure as starting quarterback (the Cardinal was just 10-20 in games he started), Edwards was a highly-touted quarterback prospect in the [[2007 NFL Draft]] due to his arm strength, accuracy, and intelligence.<ref name="ScottWright">{{cite web|title=Trent Edwards Scouting Report |

|||

* In [[ring theory]], a branch of [[abstract algebra]], the term “[[prime element]]” has a specific meaning. Here, a non-zero, non-unit ring element ''a'' is defined to be prime if whenever ''a'' divides ''bc'' for ring elements ''b'' and ''c'', then ''a'' divides at least one of ''b'' or ''c''. With this meaning, the additive inverse of any prime number is also prime. In other words, when considering the set of [[integer]]s as a [[ring (mathematics)|ring]], −7 is a prime element. Without further specification, however, “prime number” always means a positive integer prime. Among rings of [[complex number|complex]] [[algebraic integer]]s, [[Eisenstein prime]]s and [[Gaussian prime]]s may also be of interest. |

|||

| work =Scott Wright's NFL Draft Countdown |

|||

* In [[knot theory]], a [[prime knot]] is a [[knot (mathematics)|knot]] which can not be written as the knot sum of two lesser nontrivial knots. |

|||

| date =2007 |

|||

| url =http://www.nfldraftcountdown.com/scoutingreports/qb/trentedwards.html |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-31 }}</ref> Prior to the draft, [[Mel Kiper]] projected Edwards as the third-best [[quarterback]] in the draft, behind [[JaMarcus Russell]] and [[Brady Quinn]]. <ref name="USA Today">{{cite web| work =USA Today |

|||

| date =April 25, 2007 |

|||

| title =Third QB? Why Not Trent Edwards? |

|||

| url =http://www.usatoday.com/sports/football/draft/2007-04-25-trent-edwards_N.htm |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-10-09 }}</ref> |

|||

== |

==History== |

||

[[Image:Animation Sieve of Eratosth-2.gif|thumb|300px|The '''[[Sieve of Eratosthenes]]''' is a simple, ancient [[algorithm]] for finding all prime numbers up to a specified integer. It is the predecessor to the modern [[Sieve of Atkin]], which is faster but more complex. The eponymous Sieve of Eratosthenes was created in the 3rd century BC by [[Eratosthenes]], an [[ancient Greece|ancient Greek]] [[mathematician]].]] |

|||

Edwards was drafted by the [[Buffalo Bills]] in the third round with the 92nd overall pick. Edwards was a part of the [[Willis McGahee]] trade that sent him to the [[Baltimore Ravens]] for the third round pick in March 2007. After the draft, [[Bill Walsh]], the [[NFL Hall of Fame|Hall of Fame]] head coach contacted Bills General Manager [[Marv Levy]] to express his confidence in Edwards' abilities. <ref name="espn2007">{{cite web|url=http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/wire?section=nfl&id=3038418|publisher=ESPN|title=Rookie QB Trent Edwards gets chance to spark Bills offense in 1st start|date=[[September 27]] [[2007]]|accessdate=2008-02-18}}</ref> |

|||

There are hints in the surviving records of the [[ancient Egypt]]ians that they had some knowledge of prime numbers: the [[Egyptian fraction]] expansions in the [[Rhind papyrus]], for instance, have quite different forms for primes and for composites. However, the earliest surviving records of the explicit study of prime numbers come from the [[Ancient Greece|Ancient Greeks]]. [[Euclid's Elements]] (circa 300 BC) contain important theorems about primes, including the infinitude of primes and the [[fundamental theorem of arithmetic]]. Euclid also showed how to construct a [[perfect number]] from a [[Mersenne prime]]. The [[Sieve of Eratosthenes]], attributed to [[Eratosthenes]], is a simple method to compute primes, although the large primes found today with computers are not generated this way. |

|||

After the Greeks, little happened with the study of prime numbers until the 17th century. In 1640 [[Pierre de Fermat]] stated (without proof) [[Fermat's little theorem]] (later proved by [[Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz|Leibniz]] and [[Leonhard Euler|Euler]]). A special case of Fermat's theorem may have been known much earlier by the Chinese. Fermat conjectured that all numbers of the form 2<sup>2<sup>''n''</sup></sup> + 1 are prime (they are called [[Fermat number]]s) and he verified this up to ''n'' = 4 (or 2<sup>16</sup>+1). However, the very next Fermat number 2<sup>32</sup>+1 is composite (one of its prime factors is 641), as Euler discovered later, and in fact no further Fermat numbers are known to be prime. The French monk [[Marin Mersenne]] looked at primes of the form 2<sup>''p''</sup> - 1, with ''p'' a prime. They are called [[Mersenne prime]]s in his honor. |

|||

He made his [[NFL]] debut on [[September 23]] [[2007]] in a game against the [[New England Patriots]], after the Bills' starter [[J. P. Losman]] was injured in the first quarter. He was the first quarterback from the draft class of 2007 to play in the [[NFL]]. |

|||

Euler's work in number theory included many results about primes. He [[Proof that the sum of the reciprocals of the primes diverges|showed]] the [[infinite sum|infinite series]] <sup>1</sup>/<sub>2</sub> + <sup>1</sup>/<sub>3</sub> + <sup>1</sup>/<sub>5</sub> + <sup>1</sup>/<sub>7</sub> + <sup>1</sup>/<sub>11</sub> + … is divergent. |

|||

In his first game, Edwards was 10 of 20 for 97 yards with no touchdowns and one interception. In his first [[NFL]] start on [[September 30]] [[2007]] against the [[New York Jets]], he went 22-28 with 234 yards with 1 touchdown and 1 interception and led the Bills to their first win in the 2007 season. His first NFL touchdown was a 1 yard play action pass on fourth and goal to [[Michael Gaines]]. In his second start, against the [[Dallas Cowboys]] on the following week's [[Monday Night Football]], Edwards completed 23 of 31 pass attempts for 176 yards and 1 interception. |

|||

In 1747 he showed that the even perfect numbers are precisely the integers of the form 2<sup>''p''-1</sup>(2<sup>''p''</sup>-1) where the second factor is a Mersenne prime. It is believed no odd perfect numbers exist, but there is still no proof. |

|||

At the start of the 19th century, Legendre and Gauss independently conjectured that as ''x'' tends to infinity, the number of primes up to ''x'' is asymptotic to ''x''/log(''x''), where log(''x'') is the natural logarithm of ''x''. Ideas of Riemann in his 1859 paper on the zeta-function sketched a program which would lead to a proof of the prime number theorem. This outline was completed by [[Jacques Hadamard|Hadamard]] and [[Charles de la Vallée-Poussin|de la Vallée Poussin]], who independently proved the prime number theorem in 1896. |

|||

{{Externalimage |

|||

|align=right |

|||

|width=300px |

|||

|image1=[http://assets.buffalobills.com/uploads/players/F21D8212FE2E4900A66265B6A159E2E7.jpg Faceshot] |

|||

}} |

|||

Proving a number is prime is not done (for large numbers) by trial division. Many mathematicians have worked on [[primality test]]s for large numbers, often restricted to specific number forms. This includes [[Pépin's test]] for Fermat numbers (1877), [[Proth's theorem]] (around 1878), the [[Lucas–Lehmer test for Mersenne numbers]] (originated 1856),<ref>[http://primes.utm.edu/notes/by_year.html The Largest Known Prime by Year: A Brief History] [http://primes.utm.edu/curios/page.php?number_id=135 Prime Curios!: 17014…05727 (39-digits)]</ref> and the generalized [[Lucas–Lehmer test]]. More recent algorithms like [[Adleman-Pomerance-Rumely primality test|APRT-CL]], [[Elliptic curve primality proving|ECPP]] and [[AKS primality test|AKS]] work on arbitrary numbers but remain much slower. |

|||

In October, Edwards injured his wrist during a game against the [[New York Jets]] and Losman regained the starting position. Following some poor performances by Losman, particularly in a division contest against New England and a conference game against the Jaguars, on [[November 26]] [[2007]], Bills coach [[Dick Jauron]] again named Edwards the starter against the [[Washington Redskins]].<ref name=tsn>{{cite web|url=http://www.sportsnetwork.com/default.asp?c=sportsnetwork&page=/nfl/news/ABN4114579.htm|publisher=The Sports Network|title=Bills Name Edwards Starter|date=[[November 26]] [[2007]]|accessdate=2007-11-26}}</ref> Edwards led the Bills to victory over the Redskins, throwing no interceptions and leading his first fourth-quarter comeback, completing three passes to set up the game-winning field goal, for which he was named the NFL Rookie of the Week.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.buffalonews.com/sports/story/220527.html |title=Emotional rescue for Bills}}</ref> The following week against |

|||

the winless [[Miami Dolphins]], he passed for 165 yards and a career high four touchdown passes with no interceptions to lead the Bills to a 38-17 win. Despite losing the last three games of the season, Edwards was named to the all-rookie team after the season was completed. |

|||

For a long time, prime numbers were thought to have no possible application outside of [[pure mathematics]];{{Fact|date=August 2008}} this changed in the 1970s when the concepts of [[public-key cryptography]] were invented, in which prime numbers formed the basis of the first algorithms such as the [[RSA]] cryptosystem algorithm. |

|||

In 2008 Trent Edwards currently has completed 67 percent of his passes with a quarterback rating of 96.6. He has thrown three touchdowns to one interception and has led two consecutive fourth quarter comebacks against the Jacksonville Jaguars on the road and the Oakland Raiders at home. The 2008 Buffalo Bills are 4-0 under his tenure. On Sunday October 5th 2008 when the Bills Played the Cardinals Trent Edwards was hit hard into the ground on the third play of the game. He did not return. Trent Edward suffered a concussion from the hit. |

|||

Since 1951 all the [[largest known prime]]s have been found by [[computer]]s. The search for ever larger primes has generated interest outside mathematical circles. The [[Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search]] and other [[distributed computing]] projects to find large primes have become popular in the last ten to fifteen years, while mathematicians continue to struggle with the theory of primes. |

|||

==Personal life== |

|||

Edwards lives in a house in the [[South Towns]] with his older sister Shelby. |

|||

== |

===Primality of one=== |

||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

|||

Until the 19th century, most mathematicians considered the number 1 a prime, with the definition being just that a prime is divisible only by 1 and itself but not requiring a specific number of distinct divisors. There is still a large body of mathematical work that is valid despite labelling 1 a prime, such as the work of [[Moritz Abraham Stern|Stern]] and Zeisel. [[Derrick Norman Lehmer]]'s list of primes up to 10,006,721, reprinted as late as 1956,<ref>Hans Riesel, ''Prime Numbers and Computer Methods for Factorization''. New York: Springer (1994): 36</ref> started with 1 as its first prime.<ref>Richard K. Guy & John Horton Conway, ''The Book of Numbers''. New York: Springer (1996): 129 - 130</ref> [[Henri Lebesgue]] is said to be the last professional mathematician to call 1 prime.{{Fact|date=September 2008}} The change in label occurred so that the [[fundamental theorem of arithmetic]], as stated, is valid, ''i.e.'', “each number has a unique factorization into primes.”<ref>{{cite book|last=Gowers|first=T|authorlink=William Timothy Gowers|year=2002|pages=118|quote=The seemingly arbitrary exclusion of 1 from the definition of a prime … does not express some deep fact about numbers: it just happens to be a useful convention, adopted so there is only one way of factorizing any given number into primes|title=Mathematics: A Very Short Introduction|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|id=ISBN 0-19-285361-9}}</ref><ref>"[http://primes.utm.edu/notes/faq/one.html "Why is the number one not prime?"]". Retrieved 2007-10-02.</ref> Furthermore, the prime numbers have several properties that the number 1 lacks, such as the relationship of the number to its corresponding value of [[Euler's totient function]] or the sum of divisors function.<ref>"[http://www.geocities.com/primefan/Prime1ProCon.html "Arguments for and against the primality of 1]".</ref> |

|||

|- bgcolor="#ffffff |

|||

! colspan="2" bgcolor="#ffffff" | |

|||

==Prime divisors== |

|||

! rowspan="99" bgcolor="#ffffff" | |

|||

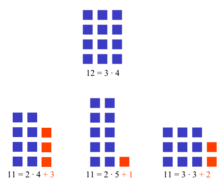

[[Image:Prime rectangles.png|thumb|Illustration showing that 11 is a prime number while 12 is not.]] |

|||

! colspan="9" | Passing |

|||

! rowspan="99" bgcolor="#ffffff" | |

|||

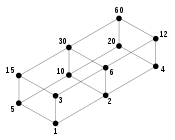

The [[fundamental theorem of arithmetic]] states that every positive integer larger than 1 can be written as a product of one or more primes in a way which is [[unique]] except possibly for the order of the prime [[divisor|factors]]. The same prime factor may occur multiple times. Primes can thus be considered the “basic building blocks” of the natural numbers. For example, we can write |

|||

! colspan="3" | Rushing |

|||

|- bgcolor="#e0e0e0" |

|||

: <math>23244 = 2^2 \times 3 \times 13 \times 149</math> |

|||

! Season |

|||

! Team |

|||

and any other factorization of 23244 as the product of primes will be identical except for the order of the factors. There are many [[Integer factorization|prime factorization]] algorithms to do this in practice for larger numbers. |

|||

! GP |

|||

! ALIGH="center" | GS |

|||

The importance of this theorem is one of the reasons for the exclusion of 1 from the set of prime numbers. If 1 were admitted as a prime, the precise statement of the theorem would require additional qualifications. |

|||

! Comp |

|||

! Att |

|||

==Properties== |

|||

! Pct |

|||

* When written in [[base 10]], all prime numbers except 2 and 5 end in 1, 3, 7 or 9. (Numbers ending in 0, 2, 4, 6 or 8 represent multiples of 2 and numbers ending in 0 or 5 represent multiples of 5.) |

|||

! Yds |

|||

* If ''p'' is a prime number and ''p'' divides a product ''ab'' of integers, then ''p'' divides ''a'' or ''p'' divides ''b''. This proposition was proved by Euclid and is known as [[Euclid's lemma]]. It is used in some proofs of the uniqueness of prime factorizations. |

|||

! Rating |

|||

* The [[ring (algebra)|ring]] '''Z'''/''n'''''Z''' (see [[modular arithmetic]]) is a [[field (mathematics)|field]] [[if and only if]] ''n'' is a prime. Put another way: ''n'' is prime if and only if [[Euler's totient function|φ(''n'')]] = ''n'' − 1. |

|||

! TD |

|||

* If ''p'' is prime and ''a'' is any integer, then ''a''<sup>''p''</sup> − ''a'' is divisible by ''p'' ([[Fermat's little theorem]]). |

|||

! INT |

|||

* If ''p'' is a prime number other than 2 and 5, <sup>1</sup>/<sub>''p''</sub> is always a [[recurring decimal]], whose period is ''p'' − 1 or a divisor of ''p'' − 1. This can be deduced directly from [[Fermat's little theorem]]. <sup>1</sup>/<sub>''p''</sub> expressed likewise in base ''q'' (other than base 10) has similar effect, provided that ''p'' is not a prime factor of ''q''. The article on [[recurring decimal]]s shows some of the interesting properties. |

|||

! Att |

|||

* An integer ''p'' > 1 is prime if and only if the [[factorial]] (''p'' − 1)! + 1 is divisible by ''p'' ([[Wilson's theorem]]). Conversely, an integer ''n'' > 4 is composite if and only if (''n'' − 1)! is divisible by ''n''. |

|||

! Yds |

|||

* If ''n'' is a positive integer greater than 1, then there is always a prime number ''p'' with ''n'' < ''p'' < 2''n'' ([[Bertrand's postulate]]). |

|||

! TD |

|||

* Adding the reciprocals of all primes together results in a divergent [[infinite series]] ([[Proof that the sum of the reciprocals of the primes diverges|proof]]). More precisely, if ''S''(''x'') denotes the sum of the reciprocals of all prime numbers ''p'' with ''p'' ≤ ''x'', then ''S''(''x'') = ln ln ''x'' + [[Big O notation|O]](1) for ''x'' → ∞. |

|||

|- bgcolor="#f0f0f0" |

|||

* In every arithmetic progression ''a'', ''a'' + ''q'', ''a'' + 2''q'', ''a'' + 3''q'', … where the positive integers ''a'' and ''q'' are [[coprime]], there are infinitely many primes ([[Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions]]). |

|||

| 2007 |

|||

* The [[Characteristic (algebra)|characteristic]] of every field is either zero or a prime number. |

|||

| [[Buffalo Bills|Buffalo]] |

|||

* If ''G'' is a finite [[group (mathematics)|group]] and ''p''<sup>''n''</sup> is the [[p-adic order|highest power of the prime ''p'' which divides]] the order of ''G'', then ''G'' has a subgroup of order ''p''<sup>''n''</sup>. ([[Sylow theorems]].) |

|||

| 10 |

|||

* If ''G'' is a finite group and ''p'' is a prime number dividing the order of ''G'', then ''G'' contains an element of order ''p''. ([[Cauchy's theorem (group theory)|Cauchy Theorem]]) |

|||

| 9 |

|||

* The [[prime number theorem]] says that the proportion of primes less than ''x'' is asymptotic to <sup>1</sup>/<sub>ln ''x''</sub> (in other words, as ''x'' gets very large, the likelihood that a number less than ''x'' is prime is inversely proportional to the number of digits in ''x''). |

|||

| 151 |

|||

* The [[Copeland-Erdős constant]] 0.235711131719232931374143…, obtained by concatenating the prime numbers in [[Decimal|base ten]], is known to be an [[irrational number]]. |

|||

| 269 |

|||

* The value of the [[Riemann zeta function]] at each point in the complex plane is given as a meromorphic continuation of a function, defined by a product over the set of all primes for Re(''s'') > 1: |

|||

| 56.1 |

|||

::<math>\zeta(s)= |

|||

| 1630 |

|||

\sum_{n=1}^\infin \frac{1}{n^s} = \prod_{p} \frac{1}{1-p^{-s}}.</math> |

|||

| 70.4 |

|||

:Evaluating this identity at different integers provides an infinite number of products over the primes whose values can be calculated, the first two being |

|||

| 8 |

|||

::<math>\prod_{p} \frac{1}{1-p^{-1}} = \infty</math> |

|||

| 8 |

|||

::<math>\prod_{p} \frac{1}{1-p^{-2}}= \frac{\pi^2}{6}.</math> |

|||

| 14 |

|||

* If ''p'' > 1, the polynomial <math> x^{p-1}+x^{p-2}+ \cdots + 1 </math> is irreducible over '''Z'''/''p'''''Z''' if and only if ''p'' is prime. |

|||

| 49 |

|||

* An integer n is prime if and only if the <math> nth </math> [[Chebyshev polynomial]] of the first kind <math> T_{n}(x) </math>, divided by <math> x </math> is irreducible in <math> Z[x] </math>. Also <math> T_{n}(x) \equiv x^n </math> if and only if <math> n </math> is prime. |

|||

| 0 |

|||

* All prime numbers above 3 are of the form 6''n'' − 1 or 6''n'' + 1, because all other numbers are divisible by 2 or 3. Generalizing this, all prime numbers above ''q'' are of form [[primorial|''q''#]]·''n'' + ''m'', where 0 < ''m'' < ''q'', and ''m'' has no prime factor ≤ ''q''. |

|||

|} |

|||

===Classification=== |

|||

Two ways of classifying prime numbers, class ''n''+ and class ''n''−, were studied by [[Paul Erdős]] and [[John Selfridge]]. |

|||

Determining the class ''n''+ of a prime number ''p'' involves looking at the largest prime factor of ''p'' + 1. If that largest prime factor is 2 or 3, then ''p'' is class 1+. But if that largest prime factor is another prime ''q'', then the class ''n''+ of ''p'' is one more than the class ''n''+ of ''q''. Sequences {{OEIS2C|id=A005105}} through {{OEIS2C|id=A005108}} list class 1+ through class 4+ primes. |

|||

The class ''n''− is almost the same as class ''n''+, except that the factorization of ''p'' − 1 is looked at instead. |

|||

==The number of prime numbers== |

|||

===There are infinitely many prime numbers=== |

|||

The oldest known proof for the statement that there are [[infinitely]] many prime numbers is given by the Greek mathematician Euclid in his ''Elements'' (Book IX, Proposition 20). Euclid states the result as "there are more than any given [finite] number of primes", and his proof is essentially the following: |

|||

<blockquote>Consider any finite set of primes. Multiply all of them together and add one (see [[Euclid number]]). The resulting number is not divisible by any of the primes in the finite set we considered, because dividing by any of these would give a remainder of one. Because all non-prime numbers can be decomposed into a product of underlying primes, then either this resultant number is prime itself, or there is a prime number or prime numbers which the resultant number could be decomposed into but are not in the original finite set of primes. Either way, there is at least one more prime that was not in the finite set we started with. This argument applies no matter what finite set we began with. So there are more primes than any given finite number.</blockquote> |

|||

This previous argument explains why the product ''P'' of finitely many primes plus 1 must be divisible by some prime not among those finitely many primes (possibly itself). |

|||

The proof is sometimes phrased in a way that falsely leads some readers to think that ''P'' + 1 must itself be prime, and think that Euclid's proof says the prime product plus 1 is always prime. This confusion especially arises when ''P'' is assumed to be the [[primorial|product of the first primes]]. The smallest counterexample with composite ''P'' + 1 is (2 × 3 × 5 × 7 × 11 × 13) + 1 = 30,031 = 59 × 509 (both primes). See also [[Euclid's theorem]]. |

|||

Other mathematicians have given other proofs. One of these (due to [[Leonhard Euler|Euler]]) shows that [[proof that the sum of the reciprocals of the primes diverges|the sum of the reciprocals of all prime numbers diverges]]. |

|||

Another [[Fermat number#Basic properties| proof]] based on [[Fermat number]]s was given by [[Christian Goldbach|Goldbach]].<ref>[http://www.math.dartmouth.edu/~euler/correspondence/letters/OO0722.pdf Letter] in [[Latin]] from Goldbach to Euler, July 1730.</ref> |

|||

[[Ernst Kummer|Kummer]]'s is particularly elegant<ref>P. Ribenboim: ''The Little Book of Bigger Primes'', second edition, Springer, 2004, p. 4.</ref> and [[Harry Furstenberg]] provides [[Furstenberg's proof of the infinitude of primes|one using general topology]].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Furstenberg, Harry.|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/2307043|title=On the infinitude of primes|journal=[[American Mathematical Monthly|Amer. Math. Monthly]]|volume=62|issue=5|year=1955|pages=353|doi=10.2307/2307043}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Furstenberg's proof that there are infinitely many prime numbers|url=http://www.everything2.com/index.pl?node_id=1460203|accessdate=2006-11-26|work=[[Everything2]]}}</ref> |

|||

===Counting the number of prime numbers below a given number=== |

|||

Even though the total number of primes is infinite, one could still ask "Approximately how many primes are there below 100,000?", or "How likely is a random 20-digit number to be prime?". |

|||

The [[prime-counting function]] π(''x'') is defined as the number of primes up to ''x''. There are known [[algorithm]]s to compute exact values of π(''x'') faster than it would be possible to compute each prime up to ''x''. Values as large as π(10<sup>20</sup>) can be calculated quickly and accurately with modern computers. Thus, e.g., π(100,000) = 9592, and π(10<sup>20</sup>) = 2,220,819,602,560,918,840. |

|||

For larger values of ''x'', beyond the reach of modern equipment, the [[prime number theorem]] provides a good estimate: π(''x'') is approximately ''x''/ln(''x''). Even better estimates are known. |

|||

==Location of prime numbers== |

|||

===Finding prime numbers=== |

|||

The ancient [[sieve of Eratosthenes]] is a simple way to compute all prime numbers up to a given limit, by making a list of all integers and repeatedly striking out multiples of already found primes. The modern [[sieve of Atkin]] is more complicated, but faster when properly optimized. |

|||

In practice one often wants to check whether a given number is prime, rather than generate a list of primes. Further, it is often satisfactory to know the answer with a high [[probability]]. It is possible to quickly check whether a given large number (say, up to a few thousand digits) is prime using probabilistic [[primality test]]s. These typically pick a random number called a "witness" and check some formula involving the witness and the potential prime ''N''. After several iterations, they declare ''N'' to be "definitely composite" or "probably prime". Some of these tests are not perfect: there may be some composite numbers, called [[pseudoprime]]s for the respective test, that will be declared "probably prime" no matter what witness is chosen. However, the most popular probabilistic tests do not suffer from this drawback. |

|||

One method for determining whether a number is prime is to divide by all primes less than or equal to the square root of that number. If any of the divisions come out as an integer, then the original number is not a prime. Otherwise, it is a prime. One need not actually calculate the square root; once one sees that the [[quotient]] is less than the divisor, one can stop. More precisely, the last prime factor possibility for some number ''N'' would be Prime(''m'') where Prime(''m'' + 1) squared exceeds ''N''. This is known as trial division; it is the simplest primality test and it quickly becomes impractical for testing large integers because the number of possible factors grows too rapidly as the number-to-be-tested increases. |

|||

The number of prime numbers less than ''N'' is near |

|||

: <math>\frac {N}{\ln N - 1}.</math> |

|||

So, to check ''N'' for primality the largest prime factor needed is just less than <math>\scriptstyle\sqrt{N}</math>, and so the number of such prime factor candidates would be close to |

|||

: <math>\frac {\sqrt{N}}{\ln\sqrt{N} - 1}.</math> |

|||

This increases ever more slowly with ''N'', but, because there is interest in large values for ''N'', the count is large also: for ''N'' = 10<sup> 20</sup> it is 450 million. |

|||

===Primality tests=== |

|||

{{main|primality test}} |

|||

A [[primality test|primality test algorithm]] is an algorithm which tests a number for primality, i.e. whether the number is a prime number. |

|||

* [[AKS primality test]] |

|||

* [[Fermat primality test]] |

|||

* [[Lucas-Lehmer test]] |

|||

* [[Solovay-Strassen primality test]] |

|||

* [[Miller-Rabin primality test]] |

|||

* [[Elliptic curve primality proving]] |

|||

A [[probable prime]] is an integer which, by virtue of having passed a certain test, is considered to be probably prime. Probable primes which are in fact composite (such as [[Carmichael number]]s) are called [[pseudoprime]]s. |

|||

In 2002, Indian scientists at [[IIT Kanpur]] discovered a new deterministic algorithm known as the [[AKS primality test|AKS algorithm]]. The amount of time that this algorithm takes to check whether a number N is prime depends on a [[P (complexity)|polynomial function of the number of digits of ''N'']] (i.e. of the logarithm of ''N''). |

|||

===Formulas yielding prime numbers=== |

|||

{{main|formula for primes}} |

|||

There is no known [[formula for primes]] which is more efficient at finding primes than the methods mentioned above under “Finding prime numbers”. |

|||

There is a set of [[Diophantine equations]] in 9 variables and one parameter with the following property: the parameter is prime if and only if the resulting system of equations has a solution over the natural numbers. This can be used to obtain a single formula with the property that all its ''positive'' values are prime. |

|||

There is no [[polynomial]], even in several variables, that takes only prime values. For example, the curious polynomial in one variable ''f''(''n'') = ''n''<sup>2</sup> − ''n'' + 41 yields primes for ''n'' = 0,…, 40,43 but ''f''(41) and ''f''(42) are composite. However, there are polynomials in several variables, whose positive values (as the variables take all positive integer values) are exactly the primes. |

|||

Another formula is based on Wilson's theorem mentioned above, and generates the number two many times and all other primes exactly once. There are other similar formulas which also produce primes. |

|||

====Special types of primes from formulas for primes==== |

|||

A prime ''p'' is called ''[[primorial prime|primorial]]'' or ''prime-factorial'' if it has the form ''p'' = ''n''# ± 1 for some number ''n'', where [[primorial|''n''#]] stands for the product 2 · 3 · 5 · 7 · 11 · … of all the primes ≤ n. A prime is called ''[[factorial prime|factorial]]'' if it is of the form [[factorial|''n''!]] ± 1. The first factorial primes are: |

|||

: n! − 1 is prime for n = 3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 14, 30, 32, 33, 38, 94, 166, 324, … {{OEIS2C | id=A002982}} |

|||

: n! + 1 is prime for n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 11, 27, 37, 41, 73, 77, 116, 154, 320, … {{OEIS2C | id=A002981}} |

|||

The largest known primorial prime is Π(392113) + 1, found by Heuer in 2001.<ref>[http://primes.utm.edu/top20/page.php?id=5 The Top Twenty: Primorial]</ref> The largest known factorial prime is 34790! − 1, found by Marchal, Carmody and Kuosa in 2002.<ref>[http://primes.utm.edu/top20/page.php?id=30 The Top Twenty: Factorial]</ref> It is not known whether there are infinitely many primorial or factorial primes. |

|||

Primes of the form 2<sup>''p''</sup> − 1, where ''p'' is a prime number, are known as [[Mersenne prime]]s, while primes of the form <math>2^{2^n} + 1</math> are known as [[Fermat prime]]s. Prime numbers ''p'' where 2''p'' + 1 is also prime are known as [[Sophie Germain prime]]s. The following list is of other special types of prime numbers that come from formulas: |

|||

<div style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> |

|||

* [[Wieferich prime]]s, |

|||

* [[Wilson prime]]s, |

|||

* [[Wall-Sun-Sun prime]]s, |

|||

* [[Wolstenholme prime]]s, |

|||

* [[Unique prime]]s, |

|||

* [[Newman-Shanks-Williams prime]]s (NSW primes), |

|||

* [[Smarandache-Wellin prime]]s, |

|||

* [[Wagstaff prime]]s, and |

|||

* [[Supersingular prime]]s. |

|||

</div> |

|||

Some primes are classified according to the properties of their digits in decimal or other bases. For example, numbers whose digits form a [[palindrome|palindromic]] sequence are called [[palindromic prime]]s, and a prime number is called a [[truncatable prime]] if successively removing the first digit at the left or the right yields only new prime numbers. |

|||

* For a list of special classes of prime numbers see [[List of prime numbers]] |

|||

===Distribution=== |

|||

{{further|[[Prime number theorem]]}} |

|||

[[Image:PrimeNumbersSmall.png|frame|right|The distribution of all the prime numbers in the range of 1 to 76,800, from left to right and top to bottom, where each pixel represents a number. Black pixels mean that number is prime and white means it is not prime.]] |

|||

The problem of modelling the distribution of prime numbers is a popular subject of investigation for number theorists. The occurrence of individual prime numbers among the [[natural number]]s is (so far) unpredictable, even though there are laws (such as the [[prime number theorem]] and [[Bertrand's postulate]]) that govern their average distribution. [[Leonhard Euler]] commented |

|||

:Mathematicians have tried in vain to this day to discover some order in the sequence of prime numbers, and we have reason to believe that it is a mystery into which the mind will never penetrate.<ref>Julian Havil, ''Gamma: Exploring Euler's Constant (Hardcover)''. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2003): 163</ref> |

|||

In a 1975 lecture, [[Don Zagier]] commented |

|||

<blockquote>There are two facts about the distribution of prime numbers of which I hope to convince you so overwhelmingly that they will be permanently engraved in your hearts. The first is that, despite their simple definition and role as the building blocks of the natural numbers, the prime numbers grow like weeds among the natural numbers, seeming to obey no other law than that of chance, and nobody can predict where the next one will sprout. The second fact is even more astonishing, for it states just the opposite: that the prime numbers exhibit stunning regularity, that there are laws governing their behavior, and that they obey these laws with almost military precision.</blockquote><ref>Havil (2003): 171</ref> |

|||

Additional image with [[:Image:Primenumbers2310inv.png|2310 columns]] is linked here, preserving multiples of 2, 3, 5, 7, 11 in respective columns. Predictably, prime numbers fall into columns if the numbers are arranged from left to right and the width is a multiple of a prime number. More surprisingly, when arranged in a spiral such as the [[Ulam spiral]], prime numbers cluster on certain diagonals and not others. |

|||

===Gaps between primes=== |

|||

{{main|Prime gap}} |

|||

Let ''p''<sub>''n''</sub> denote the ''n''th prime number (i.e. ''p''<sub>1</sub> = 2, ''p''<sub>2</sub> = 3, etc.). The ''gap'' ''g''<sub>''n''</sub> between the consecutive primes ''p''<sub>''n''</sub> and ''p''<sub>''n'' + 1</sub> is the difference between them, i.e. |

|||

: ''g''<sub>''n''</sub> = ''p''<sub>''n'' + 1</sub> − ''p''<sub>''n''</sub>. |

|||

We have ''g''<sub>1</sub> = 3 − 2 = 1, ''g''<sub>2</sub> = 5 − 3 = 2, ''g''<sub>3</sub> = 7 − 5 = 2, ''g''<sub>4</sub> = 11 − 7 = 4, and so on. The sequence (''g''<sub>''n''</sub>) of prime gaps has been extensively studied. |

|||

For any natural number ''N'' larger than 1, the sequence (for the notation ''N''! read [[factorial]]) |

|||

: ''N''! + 2, ''N''! + 3, …, ''N''! + ''N'' |

|||

is a sequence of ''N'' − 1 consecutive composite integers. Therefore, there exist gaps between primes which are arbitrarily large, i.e. for any natural number ''N'', there is an integer ''n'' with ''g''<sub>''n''</sub> > ''N''. (Choose ''n'' so that ''p''<sub>''n''</sub> is the greatest prime number less than ''N''! + 2.) |

|||

On the other hand, the gaps get arbitrarily small in proportion to the primes: the quotient ''g''<sub>''n''</sub>/''p''<sub>''n''</sub> [[limit (mathematics)|approaches]] zero as ''n'' approaches infinity. Note also that the [[twin prime conjecture]] asserts that ''g''<sub>''n''</sub> = 2 for infinitely many integers ''n''. |

|||

===Location of the largest known prime=== |

|||

{{main|Largest known prime|Mersenne prime}} |

|||

{{wikinews|CMSU computing team discovers another record size prime}} |

|||

{{wikinews|Distributed computing discovers largest known prime}} |

|||

{{Asof|2008|September}}, the largest known prime was discovered by the [[distributed computing]] project [[Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search]] (GIMPS): |

|||

:2<sup>43,112,609</sup> − 1. |

|||

This was found to be a prime number on August 23, 2008. This number is 12,978,189 digits long and is (chronologically) the 45th known Mersenne prime. The 46th known Mersenne prime, 2<sup>37,156,667</sup> − 1, was discovered two weeks later, but it is smaller. |

|||

Historically, the largest known prime has almost always been a Mersenne prime since the dawn of electronic computers, because there exists a particularly fast primality test for numbers of this form, the [[Lucas–Lehmer test for Mersenne numbers]]. |

|||

The largest known prime that is ''not'' a Mersenne prime is 19,249 × 2<sup>13,018,586</sup> + 1 (3,918,990 digits), a [[Proth's theorem|Proth number]]. This is also the seventh largest known prime of any form. It was found on March 26, 2007 by the [[Seventeen or Bust]] project and it brings them one step closer to solving the [[Sierpinski number|Sierpiński problem]]. |

|||

Some of the largest primes not known to have any particular form (that is, no simple formula such as that of Mersenne primes) have been found by taking a piece of semi-random binary data, converting it to a number <var>n</var>, multiplying it by 256<sup><var>k</var></sup> for some positive integer <var>k</var>, and searching for possible primes within the interval [256<sup>''k''</sup>''n'' + 1, 256<sup>''k''</sup>(''n'' + 1) − 1]. |

|||

==Awards for finding primes== |

|||

The [[Electronic Frontier Foundation]] (EFF) has offered a US$100,000 prize to the first discoverers of a prime with at least 10 million digits. They also offer $150,000 for 100 million digits, and $250,000 for 1 billion digits. In 2000 they paid out $50,000 for 1 million digits. They may pay out $100,000 to GIMPS and the [[UCLA]] mathematics department for discovering a 13 million digit prime number in August 2008.[http://www.allheadlinenews.com/articles/7012470624][http://www.tgdaily.com/content/view/39527/113/] |

|||

The [[RSA Factoring Challenge]] offered prizes up to US$200,000 for finding the prime factors of certain [[semiprime]]s of up to 2048 bits. However, the challenge was closed in 2007 after much smaller prizes for smaller semiprimes had been paid out.<ref>[http://www.rsa.com/rsalabs/node.asp?id=2092 The RSA Factoring Challenge — RSA Laboratories]</ref> |

|||

==Generalizations of the prime concept== |

|||

The concept of prime number is so important that it has been generalized in different ways in various branches of mathematics. |

|||

===Prime elements in rings=== |

|||

One can define [[prime element]]s and [[irreducible element]]s in any [[integral domain]]. For any [[unique factorization domain]], such as the ring '''Z''' of integers, the set of prime elements equals the set of irreducible elements, which for '''Z''' is {…, −11, −7, −5, −3, −2, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, …}. |

|||

As an example, we consider the [[Gaussian integer]]s '''Z'''[''i''], that is, complex numbers of the form ''a'' + ''bi'' with ''a'' and ''b'' in '''Z'''. This is an integral domain, and its prime elements are the [[Gaussian prime]]s. Note that 2 is ''not'' a Gaussian prime, because it factors into the product of the two Gaussian primes (1 + ''i'') and (1 − ''i''). The element 3, however, remains prime in the Gaussian integers. In general, rational primes (i.e. prime elements in the ring '''Z''' of integers) of the form 4''k'' + 3 are Gaussian primes, whereas rational primes of the form 4''k'' + 1 are not. |

|||

===Prime ideals=== |

|||

In [[ring theory]], one generally replaces the notion of number with that of [[ideal (ring theory)|ideal]]. ''[[Prime ideal]]s'' are an important tool and object of study in [[commutative algebra]], [[number theory|algebraic number theory]] and [[algebraic geometry]]. |

|||

The prime ideals of the ring of integers are the ideals (0), (2), (3), (5), (7), (11), … |

|||

A central problem in algebraic number theory is how a prime ideal factors when it is ''lifted'' to an extension field. For example, in the Gaussian integer example above, (2) ''ramifies'' into a prime power (1 + ''i'' and 1 − ''i'' generate the same prime ideal), prime ideals of the form (4''k'' + 3) are ''inert'' (remain prime), and prime ideals of the form (4''k'' + 1) ''split'' (are the product of 2 distinct prime ideals). |

|||

===Primes in valuation theory=== |

|||

In algebraic number theory, yet another generalization is used. Given an arbitrary [[field (mathematics)|field]] ''K'', one considers [[valuation]]s on ''K'', certain functions from ''K'' to the real numbers '''R'''. Every such valuation yields a [[topological field|topology on ''K'']], and two valuations are called ''equivalent'' if they yield the same topology. A ''prime of K'' (sometimes called a ''place of K'') is an [[equivalence class]] of valuations. With this definition, the primes of the field '''Q''' of [[rational number]]s are represented by the standard [[absolute value]] function (known as the [[infinite prime]]) as well as by the [[p-adic number|''p''-adic valuations]] on '''Q''', for every prime number ''p''. |

|||

===Prime knots=== |

|||

In [[knot theory]], a '''prime knot''' is a [[knot (mathematics)|knot]] which is, in a certain sense, indecomposable. Specifically, it is one which cannot be written as the [[knot sum]] of two nontrivial knots. |

|||

==Open questions== |

|||

There are many open questions about prime numbers. A very significant one is the [[Riemann hypothesis]], which essentially says that the primes are as regularly distributed as possible. From a physical viewpoint, it roughly states that the irregularity in the distribution of primes only comes from random noise. From a mathematical viewpoint, it roughly states that the asymptotic distribution of primes (about 1/ log ''x'' of numbers less than ''x'' are primes, the [[prime number theorem]]) also holds for much shorter intervals of length about the square root of ''x'' (for intervals near ''x''). This hypothesis is generally believed to be correct, in particular, the simplest assumption is that primes should have no significant irregularities without good reason. |

|||

Many famous conjectures appear to have a very high probability of being true (in a formal sense, many of them follow from simple heuristic probabilistic arguments): |

|||

* Prime [[Euclid number]]s: It is not known whether or not there are an infinite number of prime Euclid numbers. |

|||

* [[Goldbach's conjecture|Strong Goldbach conjecture]]: Every even integer greater than 2 can be written as a sum of two primes. |

|||

* [[Goldbach's weak conjecture|Weak Goldbach conjecture]]: Every odd integer greater than 5 can be written as a sum of three primes. |

|||

* [[Twin prime conjecture]]: There are infinitely many [[twin prime]]s, pairs of primes with difference 2. |

|||

* [[Polignac's conjecture]]: For every positive integer n, there are infinitely many pairs of consecutive primes which differ by 2''n''. When ''n'' = 1 this is the twin prime conjecture. |

|||

* A weaker form of Polignac's conjecture: Every [[even number]] is the difference of two primes. |

|||

* It is widely believed there are infinitely many [[Mersenne prime]]s, but not [[Fermat prime]]s.<ref>E.g., see {{citation|last=Guy|first=Richard K.|title=Unsolved Problems in Number Theory|publisher=Springer-Verlag|year=1981}}, problem A3, pp. 7–8.</ref> |

|||

* It is conjectured there are infinitely many primes of the form ''n''<sup>2</sup> + 1.<ref>{{MathWorld|urlname=LandausProblems|title=Landau's Problems}}</ref> |

|||

* Many well-known conjectures are special cases of the broad [[Schinzel's hypothesis H]]. |

|||

* It is conjectured that there are infinitely many [[Fibonacci prime]]s.<ref>Caldwell, Chris, [http://primes.utm.edu/top20/page.php?id=48 ''The Top Twenty: Lucas Number''] at The [[Prime Pages]].</ref> |

|||

* [[Legendre's conjecture]]: There is a prime number between ''n''<sup>2</sup> and (''n'' + 1)<sup>2</sup> for every positive integer ''n''. |

|||

* [[Cramér's conjecture]]: <math>\limsup_{n\rightarrow\infty} \frac{p_{n+1}-p_n}{(\log p_n)^2} = 1</math>. This conjecture implies Legendre's, but its status is more unsure. |

|||

* [[Brocard's conjecture]]: There are always at least four primes between the squares of consecutive primes greater than 2. |

|||

All four of [[Landau's problems]] from 1912 are listed above and still unsolved: Goldbach, twin primes, Legendre, ''n''<sup>2</sup>+1 primes. |

|||

==Applications== |

|||

For a long time, number theory in general, and the study of prime numbers in particular, was seen as the canonical example of pure mathematics, with no applications outside of the self-interest of studying the topic. In particular, number theorists such as [[United Kingdom|British]] mathematician [[G. H. Hardy]] prided themselves on doing work that had absolutely no military significance.<ref>{{cite book|quote = No one has yet discovered any warlike purpose to be served by the theory of numbers or relativity, and it seems unlikely that anyone will do so for many years | last = Hardy | first = G.H. | authorlink = G. H. Hardy | title = [[A Mathematician's Apology]] | publisher = [[Cambridge University Press]] | year = 1940 | id = ISBN 0-521-42706-1 }}</ref> However, this vision was shattered in the 1970s, when it was publicly announced that prime numbers could be used as the basis for the creation of [[public key cryptography]] algorithms. Prime numbers are also used for [[hash table]]s and [[pseudorandom number generator]]s. |

|||

Some [[rotor machine]]s were designed with a different number of pins on each rotor, with the number of pins on any one rotor either prime, or [[coprime]] to the number of pins on any other rotor. |

|||

This helped generate the [[full cycle]] of possible rotor positions before repeating any position. |

|||

===Public-key cryptography=== |

|||

{{main|public key cryptography}} |

|||

Several public-key cryptography algorithms, such as [[RSA]], are based on large prime numbers (for example with 512 [[bit]]s). |

|||

===Prime numbers in nature=== |

|||

Many numbers occur in nature, and inevitably some of these are prime. There are, however, relatively few examples of numbers that appear in nature ''because'' they are prime. For example, most [[starfish]] have 5 arms, and 5 is a prime number. However there is no evidence to suggest that starfish have 5 arms ''because'' 5 is a prime number. Indeed, some starfish have different numbers of arms. ''Echinaster luzonicus'' normally has six arms, ''Luidia senegalensis'' has nine arms, and ''Solaster endeca'' can have as many as twenty arms. Why the majority of starfish (and most other [[echinoderms]]) have [[Symmetry (biology)#Pentamerism|five-fold symmetry]] remains a mystery. |

|||

One example of the use of prime numbers in nature is as an evolutionary strategy used by [[cicada]]s of the genus ''[[Magicicada]]''.<ref>Goles, E., Schulz, O. and M. Markus (2001). "Prime number selection of cycles in a predator-prey model", Complexity 6(4): 33-38</ref> These insects spend most of their lives as [[larva|grubs]] underground. They only pupate and then emerge from their burrows after 13 or 17 years, at which point they fly about, breed, and then die after a few weeks at most. The logic for this is believed to be that the prime number intervals between emergences makes it very difficult for predators to evolve that could specialise as predators on ''Magicicadas''.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Paulo R. A. Campos, Viviane M. de Oliveira, Ronaldo Giro, and Douglas S. Galvão. | url = http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v93/e098107 | title = Emergence of Prime Numbers as the Result of Evolutionary Strategy | journal = [[Physical Review Letters|Phys. Rev. Lett.]] | volume = 93 | doi = 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.098107 | year = 2004 | accessdate = 2006-11-26 | pages = 098107 }}</ref> If ''Magicicadas'' appeared at a non-prime number intervals, say every 12 years, then predators appearing every 2, 3, 4, 6, or 12 years would be sure to meet them. Over a 200-year period, average predator populations during hypothetical outbreaks of 14- and 15-year cicadas would be up to 2% higher than during outbreaks of 13- and 17-year cicadas.<ref>{{cite web |work=[[The Economist]]| url=http://economist.com/PrinterFriendly.cfm?Story_ID=2647052 |title=Invasion of the Brood |date=May 6, 2004|accessdate=2006-11-26 }}</ref> Though small, this advantage appears to have been enough to drive natural selection in favour of a prime-numbered life-cycle for these insects. |

|||

There is speculation that the zeros of the [[zeta function]] are connected to the energy levels of complex quantum systems. <ref>{{cite web |author=Ivars Peterson | work=[[MAA Online]]| url=http://www.maa.org/mathland/mathtrek_6_28_99.html |title=The Return of Zeta |date=June 28, 1999|accessdate=2008-03-14 }}</ref> |

|||

==In the arts and literature== |

|||

Prime numbers have influenced many artists and writers. The French [[composer]] [[Olivier Messiaen]] used prime numbers to create ametrical music through "natural phenomena". In works such as ''La Nativité du Seigneur'' (1935) and ''Quatre études de rythme'' (1949-50), he simultaneously employs motifs with lengths given by different prime numbers to create unpredictable rhythms: the primes 41, 43, 47 and 53 appear in one of the études. According to Messiaen this way of composing was "inspired by the movements of nature, movements of free and unequal durations". <ref> The Messiaen companion', ed. Peter Hill, Amadeus Press, 1994. ISBN 0-931340-95-0 </ref> |

|||

In his science fiction novel ''[[Contact (novel)|Contact]]'', later made into a [[Contact (film)|film of the same name]], the [[NASA]] scientist [[Carl Sagan]] suggested that prime numbers could be used as a means of communicating with aliens, an idea that he had first developed informally with American astronomer [[Frank Drake]] in 1975. <ref>[[Carl Pomerance]], [http://www.math.dartmouth.edu/~carlp/PDF/extraterrestrial.pdf Prime Numbers and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence], Retrieved on December 22, 2007</ref> |

|||

[[Tom Stoppard]]'s award-winning 1993 play ''[[Arcadia (play)|Arcadia]]'' was a conscious attempt to discuss mathematical ideas on the stage. In the opening scene, the 13 year old heroine puzzles over [[Fermat's Last Theorem]], a theorem involving prime numbers. <ref> Tom Stoppard, Arcadia, Faber and Faber, 1993. ISBN 0-571-16934-1.</ref> |

|||

<ref> ''The Cambridge Companion to Tom Stoppard'', ed. Katherine E. Kelly, Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0521645921 </ref> <ref> |

|||

[http://www.msri.org/communications/forsale/arcadia The Mathematics of Arcadia], an event involving Tom Stoppard and [[MSRI]] in the [[University of California, Berkeley]]</ref> |

|||

Many films reflect a popular fascination with the mysteries of prime numbers and cryptography: films such as ''[[Cube (film)| Cube]]'', ''[[Sneakers (film)|Sneakers]]'', ''[[The Mirror Has Two Faces]]'' and ''[[A Beautiful Mind (film)|A Beautiful Mind]]'', the latter of which is based on the biography of the mathematician and Nobel laureate [[John Forbes Nash]] by [[Sylvia Nasar]].<ref> [http://www.musicoftheprimes.com/films.htm Music of the Spheres], [[Marcus du Sautoy]]'s selection of films featuring prime numbers</ref> <ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20020611080521/http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/n/nasar-mind.html A Beautiful Mind]</ref> |

|||

In the novel [[PopCo]] by [[Scarlett Thomas]] the main character, Alice Butler's grandmother works on proving the [[Riemann Hypothesis]]. In the book, a table of the first 1000 prime numbers is displayed.<ref>[http://math.cofc.edu/kasman/MATHFICT/mfview.php?callnumber=mf476 - A Mathematician reviews PopCo]</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

<div style="-moz-column-count:3; column-count:3;"> |

|||

* [[Full cycle]] |

|||

* [[Gödel number]] |

|||

* [[Hilbert number]] |

|||

* [[Integer factorization]] |

|||

* [[Irreducible polynomial]] |

|||

* [[Logarithmic integral function]] |

|||

* [[Prime power]] |

|||

* [[Primon gas]] |

|||

* [[Sphenic number]] |

|||

* [[List of prime numbers]] (list of special classes of prime numbers) |

|||

</div> |

|||

==Distributed computing projects that search for primes== |

|||

*[[Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search|GIMPS]] searches for [[Mersenne prime]]s. |

|||

*[[PrimeGrid]] searches for [[megaprime]]s. |

|||

*[[Seventeen or Bust]] searches for primes which can help prove that 78557 is the smallest [[Sierpinski number]]. |

|||

*[[Twin Prime Search]] searches for record [[twin prime]]s |

|||

*[[Wieferich@Home]] searches for [[Wieferich prime]]s. |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{ |

{{refbegin}} |

||

* John Derbyshire, ''Prime Obsession: Bernhard Riemann and the Greatest Unsolved Problem in Mathematics''. Joseph Henry Press; 448 pages |

|||

* Wladyslaw Narkiewicz, ''The development of prime number theory. From Euclid to Hardy and Littlewood''. Springer Monographs in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2000. |

|||

* H. Riesel, ''Prime Numbers and Computer Methods for Factorization'', 2nd ed., Birkhäuser 1994. |

|||

* Marcus du Sautoy, ''The Music of the Primes: Searching to Solve the Greatest Mystery in Mathematics''. HarperCollins; 352 pages. ISBN 0-06-621070-4. [http://www.musicoftheprimes.com/ The Music of Primes website]. |

|||

* Karl Sabbagh, ''The Riemann Hypothesis: The Greatest Unsolved Problem in Mathematics''. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 340 pages |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Wikinews|Two largest known prime numbers discovered just two weeks apart, one qualifies for $100k prize}} |

|||

*[http://www.buffalobills.com/team/player.jsp?player_id=122719 Official Buffalo Bills Profile] |

|||

*{{nfl player|id=EDW720778|name=Trent Edwards}} |

|||

*{{espn nfl|id=10536|name=Trent Edwards}} |

|||

*{{pro-football-reference|id=EdwaTr01|name=Trent Edwards}} |

|||

*{{imdb|2635018}} |

|||

*{{youtube|6ODRNj_-6qI|Trent Edwards profile}} |

|||

* Caldwell, Chris, The [[Prime Pages]] at [http://primes.utm.edu/ primes.utm.edu]. |

|||

{{start box}} |

|||

* [http://mathworld.wolfram.com/topics/PrimeNumbers.html Prime Numbers at MathWorld] |

|||

{{succession box | title=Stanford Starting Quarterbacks | before=[[Chris Lewis (quarterback)|Chris Lewis]]| years=2004-2006| after=[[T. C. Ostrander]]}} |

|||

* [http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/history/HistTopics/Prime_numbers.html MacTutor history of prime numbers] |

|||

{{succession box | title=Buffalo Bills Starting Quarterbacks | before=[[J.P. Losman]]| years=2007| after=Incumbent}} |

|||

* [http://www.primepuzzles.net/ The prime puzzles] |

|||

{{end box}} |

|||

* [http://aleph0.clarku.edu/~djoyce/java/elements/bookIX/propIX20.html An English translation of Euclid's proof that there are infinitely many primes] |

|||

* [http://www.numberspiral.com/index.html Number Spiral with prime patterns] |

|||

* [http://www.maths.ex.ac.uk/~mwatkins/zeta/vardi.html An Introduction to Analytic Number Theory, by Ilan Vardi and Cyril Banderier] |

|||

* [http://www.eff.org/awards/coop.php EFF Cooperative Computing Awards] |

|||

* ''[http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/WhyANumberIsPrime/ Why a Number Is Prime]'' by Enrique Zeleny, [[The Wolfram Demonstrations Project]]. |

|||

===Prime number generators & calculators=== |

|||

* [http://www.numberempire.com/primenumbers.php Online Prime Number Generator and Checker] - instantly checks and finds prime numbers up to 128 digits long (does NOT require Java or Javascript) |

|||

* [http://www.easycalculation.com/prime-number.php Prime number calculator] — Check prime number, and find next largest and next smallest prime numbers (requires Javascript). |

|||

* [http://www.alpertron.com.ar/ECM.HTM Fast Online primality test — Dario Alpern's personal site] – Makes use of the Elliptic Curve Method (up to thousands digits numbers check!, requires Java) |

|||

* [http://publicliterature.org/tools/prime_number_generator Prime Number Generator] — Generates a given number of primes above a given start number. |

|||

* [http://wims.unice.fr/wims/wims.cgi?module=tool/number/primes.en Primes] from WIMS is an online prime generator. |

|||

* [http://www.bigprimes.net/archive/prime.php Huge database of prime numbers] |

|||

[[Category:Integer sequences]] |

|||

{{NFLStartingQuarterbacks}} |

|||

[[Category:Prime numbers|*]] |

|||

{{Bills2007DraftPicks}} |

|||

[[Category:Articles containing proofs]] |

|||

{{BillsQuarterbacks}} |

|||

{{Link FA|lmo}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Edwards, Trent}} |

|||

[[Category:1983 births]] |

|||

[[Category:American football quarterbacks]] |

|||

[[Category:Armenian-Americans]] |

|||

[[Category:Buffalo Bills players]] |

|||

[[Category:Buffalo Bills quarterbacks]] |

|||

[[Category:Living people]] |

|||

[[Category:People from the San Francisco Bay Area]] |

|||

[[Category:Stanford Cardinal football players]] |

|||

[[ |

[[af:Priemgetal]] |

||

[[ |

[[ang:Frumtæl]] |

||

[[ar:عدد أولي]] |

|||

[[bn:মৌলিক সংখ্যা]] |

|||

[[zh-min-nan:Sò͘-sò͘]] |

|||

[[be-x-old:Просты лік]] |

|||

[[bs:Prost broj]] |

|||

[[br:Niveroù kentael]] |

|||

[[bg:Просто число]] |

|||

[[ca:Nombre primer]] |

|||

[[cs:Prvočíslo]] |

|||

[[cy:Rhif cysefin]] |

|||

[[da:Primtal]] |

|||

[[de:Primzahl]] |

|||

[[et:Algarv]] |

|||

[[el:Πρώτος αριθμός]] |

|||

[[es:Número primo]] |

|||

[[eo:Primo]] |

|||

[[eu:Zenbaki lehen]] |

|||

[[fa:عدد اول]] |

|||

[[fr:Nombre premier]] |

|||

[[ga:Uimhir phríomha]] |

|||

[[gl:Número primo]] |

|||

[[ko:소수 (수론)]] |

|||

[[hr:Prost broj]] |

|||

[[id:Bilangan prima]] |

|||

[[is:Frumtala (stærðfræði)]] |

|||

[[it:Numero primo]] |

|||

[[he:מספר ראשוני]] |

|||

[[ka:მარტივი რიცხვი]] |

|||

[[ht:Nonm premye]] |

|||

[[la:Numerus primus]] |

|||

[[lv:Pirmskaitlis]] |

|||

[[lb:Primzuel]] |

|||

[[lt:Pirminis skaičius]] |

|||

[[lmo:Nümar primm]] |

|||

[[hu:Prímszámok]] |

|||

[[ml:അഭാജ്യസംഖ്യ]] |

|||

[[ms:Nombor perdana]] |

|||

[[mn:Энгийн тоо]] |

|||

[[nl:Priemgetal]] |

|||

[[ja:素数]] |

|||

[[no:Primtall]] |

|||

[[nn:Primtal]] |

|||

[[uz:Tub son]] |

|||

[[nds:Primtall]] |

|||

[[pl:Liczby pierwsze]] |

|||

[[pt:Número primo]] |

|||

[[ro:Număr prim]] |

|||

[[ru:Простое число]] |

|||

[[scn:Nùmmuru primu]] |

|||

[[simple:Prime number]] |

|||

[[sk:Prvočíslo]] |

|||

[[sl:Praštevilo]] |

|||

[[sr:Прост број]] |

|||

[[fi:Alkuluku]] |

|||

[[sv:Primtal]] |

|||

[[ta:பகா எண்]] |

|||

[[th:จำนวนเฉพาะ]] |

|||

[[vi:Số nguyên tố]] |

|||

[[tr:Asal sayılar]] |

|||

[[uk:Просте число]] |

|||

[[ur:مفرد عدد]] |

|||

[[vls:Priemgetal]] |

|||

[[yi:פרימצאל]] |

|||

[[yo:Nọ́mbà àkọ́kọ́]] |

|||

[[zh-yue:質數]] |

|||

[[zh:素数]] |

|||

Revision as of 00:23, 13 October 2008

In mathematics, a prime number (or a prime) is a natural number which has exactly two distinct natural number divisors: 1 and itself. An infinitude of prime numbers exists, as demonstrated by Euclid around 300 BC. The first twenty-five prime numbers are:

- 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71, 73, 79, 83, 89, 97 (sequence A000040 in the OEIS).

See the list of prime numbers for a longer list. The number one is by definition not a prime number; see the discussion below under Primality of one. The set of prime numbers is sometimes denoted by ℙ.

The property of being a prime is called primality, and the word prime is also used as an adjective. Since two is the only even prime number, the term odd prime refers to any prime number greater than two.

The study of prime numbers is part of number theory, the branch of mathematics which encompasses the study of natural numbers. Prime numbers have been the subject of intense research, yet some fundamental questions, such as the Riemann hypothesis and the Goldbach conjecture, have been unresolved for more than a century. The problem of modelling the distribution of prime numbers is a popular subject of investigation for number theorists: when looking at individual numbers, the primes seem to be randomly distributed, but the “global” distribution of primes follows well-defined laws.

The notion of prime number has been generalized in many different branches of mathematics.

- In ring theory, a branch of abstract algebra, the term “prime element” has a specific meaning. Here, a non-zero, non-unit ring element a is defined to be prime if whenever a divides bc for ring elements b and c, then a divides at least one of b or c. With this meaning, the additive inverse of any prime number is also prime. In other words, when considering the set of integers as a ring, −7 is a prime element. Without further specification, however, “prime number” always means a positive integer prime. Among rings of complex algebraic integers, Eisenstein primes and Gaussian primes may also be of interest.

- In knot theory, a prime knot is a knot which can not be written as the knot sum of two lesser nontrivial knots.

History

There are hints in the surviving records of the ancient Egyptians that they had some knowledge of prime numbers: the Egyptian fraction expansions in the Rhind papyrus, for instance, have quite different forms for primes and for composites. However, the earliest surviving records of the explicit study of prime numbers come from the Ancient Greeks. Euclid's Elements (circa 300 BC) contain important theorems about primes, including the infinitude of primes and the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. Euclid also showed how to construct a perfect number from a Mersenne prime. The Sieve of Eratosthenes, attributed to Eratosthenes, is a simple method to compute primes, although the large primes found today with computers are not generated this way.

After the Greeks, little happened with the study of prime numbers until the 17th century. In 1640 Pierre de Fermat stated (without proof) Fermat's little theorem (later proved by Leibniz and Euler). A special case of Fermat's theorem may have been known much earlier by the Chinese. Fermat conjectured that all numbers of the form 22n + 1 are prime (they are called Fermat numbers) and he verified this up to n = 4 (or 216+1). However, the very next Fermat number 232+1 is composite (one of its prime factors is 641), as Euler discovered later, and in fact no further Fermat numbers are known to be prime. The French monk Marin Mersenne looked at primes of the form 2p - 1, with p a prime. They are called Mersenne primes in his honor.

Euler's work in number theory included many results about primes. He showed the infinite series 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/5 + 1/7 + 1/11 + … is divergent. In 1747 he showed that the even perfect numbers are precisely the integers of the form 2p-1(2p-1) where the second factor is a Mersenne prime. It is believed no odd perfect numbers exist, but there is still no proof.

At the start of the 19th century, Legendre and Gauss independently conjectured that as x tends to infinity, the number of primes up to x is asymptotic to x/log(x), where log(x) is the natural logarithm of x. Ideas of Riemann in his 1859 paper on the zeta-function sketched a program which would lead to a proof of the prime number theorem. This outline was completed by Hadamard and de la Vallée Poussin, who independently proved the prime number theorem in 1896.

Proving a number is prime is not done (for large numbers) by trial division. Many mathematicians have worked on primality tests for large numbers, often restricted to specific number forms. This includes Pépin's test for Fermat numbers (1877), Proth's theorem (around 1878), the Lucas–Lehmer test for Mersenne numbers (originated 1856),[1] and the generalized Lucas–Lehmer test. More recent algorithms like APRT-CL, ECPP and AKS work on arbitrary numbers but remain much slower.

For a long time, prime numbers were thought to have no possible application outside of pure mathematics;[citation needed] this changed in the 1970s when the concepts of public-key cryptography were invented, in which prime numbers formed the basis of the first algorithms such as the RSA cryptosystem algorithm.

Since 1951 all the largest known primes have been found by computers. The search for ever larger primes has generated interest outside mathematical circles. The Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search and other distributed computing projects to find large primes have become popular in the last ten to fifteen years, while mathematicians continue to struggle with the theory of primes.

Primality of one

Until the 19th century, most mathematicians considered the number 1 a prime, with the definition being just that a prime is divisible only by 1 and itself but not requiring a specific number of distinct divisors. There is still a large body of mathematical work that is valid despite labelling 1 a prime, such as the work of Stern and Zeisel. Derrick Norman Lehmer's list of primes up to 10,006,721, reprinted as late as 1956,[2] started with 1 as its first prime.[3] Henri Lebesgue is said to be the last professional mathematician to call 1 prime.[citation needed] The change in label occurred so that the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, as stated, is valid, i.e., “each number has a unique factorization into primes.”[4][5] Furthermore, the prime numbers have several properties that the number 1 lacks, such as the relationship of the number to its corresponding value of Euler's totient function or the sum of divisors function.[6]

Prime divisors

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic states that every positive integer larger than 1 can be written as a product of one or more primes in a way which is unique except possibly for the order of the prime factors. The same prime factor may occur multiple times. Primes can thus be considered the “basic building blocks” of the natural numbers. For example, we can write

and any other factorization of 23244 as the product of primes will be identical except for the order of the factors. There are many prime factorization algorithms to do this in practice for larger numbers.

The importance of this theorem is one of the reasons for the exclusion of 1 from the set of prime numbers. If 1 were admitted as a prime, the precise statement of the theorem would require additional qualifications.

Properties

- When written in base 10, all prime numbers except 2 and 5 end in 1, 3, 7 or 9. (Numbers ending in 0, 2, 4, 6 or 8 represent multiples of 2 and numbers ending in 0 or 5 represent multiples of 5.)

- If p is a prime number and p divides a product ab of integers, then p divides a or p divides b. This proposition was proved by Euclid and is known as Euclid's lemma. It is used in some proofs of the uniqueness of prime factorizations.

- The ring Z/nZ (see modular arithmetic) is a field if and only if n is a prime. Put another way: n is prime if and only if φ(n) = n − 1.

- If p is prime and a is any integer, then ap − a is divisible by p (Fermat's little theorem).

- If p is a prime number other than 2 and 5, 1/p is always a recurring decimal, whose period is p − 1 or a divisor of p − 1. This can be deduced directly from Fermat's little theorem. 1/p expressed likewise in base q (other than base 10) has similar effect, provided that p is not a prime factor of q. The article on recurring decimals shows some of the interesting properties.

- An integer p > 1 is prime if and only if the factorial (p − 1)! + 1 is divisible by p (Wilson's theorem). Conversely, an integer n > 4 is composite if and only if (n − 1)! is divisible by n.

- If n is a positive integer greater than 1, then there is always a prime number p with n < p < 2n (Bertrand's postulate).

- Adding the reciprocals of all primes together results in a divergent infinite series (proof). More precisely, if S(x) denotes the sum of the reciprocals of all prime numbers p with p ≤ x, then S(x) = ln ln x + O(1) for x → ∞.

- In every arithmetic progression a, a + q, a + 2q, a + 3q, … where the positive integers a and q are coprime, there are infinitely many primes (Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions).

- The characteristic of every field is either zero or a prime number.

- If G is a finite group and pn is the highest power of the prime p which divides the order of G, then G has a subgroup of order pn. (Sylow theorems.)

- If G is a finite group and p is a prime number dividing the order of G, then G contains an element of order p. (Cauchy Theorem)

- The prime number theorem says that the proportion of primes less than x is asymptotic to 1/ln x (in other words, as x gets very large, the likelihood that a number less than x is prime is inversely proportional to the number of digits in x).

- The Copeland-Erdős constant 0.235711131719232931374143…, obtained by concatenating the prime numbers in base ten, is known to be an irrational number.

- The value of the Riemann zeta function at each point in the complex plane is given as a meromorphic continuation of a function, defined by a product over the set of all primes for Re(s) > 1:

- Evaluating this identity at different integers provides an infinite number of products over the primes whose values can be calculated, the first two being

- If p > 1, the polynomial is irreducible over Z/pZ if and only if p is prime.

- An integer n is prime if and only if the Chebyshev polynomial of the first kind , divided by is irreducible in . Also if and only if is prime.

- All prime numbers above 3 are of the form 6n − 1 or 6n + 1, because all other numbers are divisible by 2 or 3. Generalizing this, all prime numbers above q are of form q#·n + m, where 0 < m < q, and m has no prime factor ≤ q.

Classification

Two ways of classifying prime numbers, class n+ and class n−, were studied by Paul Erdős and John Selfridge.

Determining the class n+ of a prime number p involves looking at the largest prime factor of p + 1. If that largest prime factor is 2 or 3, then p is class 1+. But if that largest prime factor is another prime q, then the class n+ of p is one more than the class n+ of q. Sequences OEIS: A005105 through OEIS: A005108 list class 1+ through class 4+ primes.