Palazzo Valmarana: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Mistico Dois (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| caption = |

| caption = |

||

| location = [[Vicenza]], [[Province of Vicenza]], [[Veneto]], [[Italy]] |

| location = [[Vicenza]], [[Province of Vicenza]], [[Veneto]], [[Italy]] |

||

| part_of = [[City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto]] |

| part_of = [[City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto]] |

||

| includes = <!--replace by summary if the list of sub-entities is too large or incomplete--> |

| includes = <!--replace by summary if the list of sub-entities is too large or incomplete--> |

||

| criteria = {{UNESCO WHS type|(i)(ii)}}(i)(ii) |

| criteria = {{UNESCO WHS type|(i)(ii)}}(i)(ii) |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Palazzo Valmarana''' is a palace in [[Vicenza]]. It was built by architect [[Andrea Palladio]] in 1565 for the noblewoman Isabella Nogarola Valmarana. Since 1994 it is part of the [[ |

'''Palazzo Valmarana''' is a palace in [[Vicenza]]. It was built by Italian Renaissance architect [[Andrea Palladio]] in 1565 for the noblewoman Isabella Nogarola Valmarana. Since 1994 it is part of the [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]] "[[City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto]]".<ref>[http://www.vicenzaforumcenter.it/vicenza_citta_unesco/ Forum Center - Comune Di Vicenza - Vicenza Città Unesco] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160624174813/http://www.vicenzaforumcenter.it/vicenza_citta_unesco/ |date=24 June 2016 }}</ref> |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

[[File:Isabella Nogarola Valmarana busto 2009-07-25 f03.jpg|thumb|left| |

[[File:Isabella Nogarola Valmarana busto 2009-07-25 f03.jpg|thumb|left|Bust of Isabella Nogarola Valmarana in the salon of the piano nobile]] |

||

The foundation medal of this building bears engraved the date 1566 as well as the bust of Isabella Nogarola [[Valmarana]], and it is the latter who signed the construction contracts with the builders in December 1565. Nevertheless, no doubts can remain about the role her deceased husband, Giovanni Alvise (died 1558), played in choosing Palladio as designer of his family palace. In 1549, along with Girolamo Chiericati and |

The foundation medal of this building bears engraved the date 1566 as well as the bust of Isabella Nogarola [[Valmarana]], and it is the latter who signed the construction contracts with the builders in December 1565. Nevertheless, no doubts can remain about the role her deceased husband, Giovanni Alvise (died 1558), played in choosing Palladio as designer of his family palace. In 1549, along with Girolamo Chiericati and [[Giangiorgio Trissino]], Giovanni Alvise Valmarana had publicly supported Palladio’s project for the [[Basilica Palladiana|porticoes of the Basilica Palladiana]], evidently on the basis of an opinion formed six years prior, when Giovanni Alvise supervised the execution of ephemeral structures, conceived by Palladio under Trissino’s direction, to honour the entrance into Vicenza of Bishop [[Niccolò Ridolfi]] (1543). Furthermore, it was a space designed by Palladio – the [[Valmarana Chapel]] in the church of [[Santa Corona]] – which would eventually host the mortal remains of Giovanni Alvise and Isabella, on the commission of their son Leonardo. |

||

On the site later occupied by the new 16th century (Cinquecento) palace, the Valmarana family possessed buildings right from the end of the 15th century (Quattrocento), which were progressively combined until they became the object of Palladio’s renovation. The planimetric irregularity of the internal spaces doubtless derives from the oblique orientation of the façade and of pre-existing walls. In this sense it becomes quite evident just how much the Olympian regularity of the palace illustrated in |

On the site later occupied by the new 16th century (Cinquecento) palace, the Valmarana family possessed buildings right from the end of the 15th century (Quattrocento), which were progressively combined until they became the object of Palladio’s renovation. The planimetric irregularity of the internal spaces doubtless derives from the oblique orientation of the façade and of pre-existing walls. In this sense it becomes quite evident just how much the Olympian regularity of the palace illustrated in ''[[I quattro libri dell'architettura]]'' (1570) was the product of Palladio’s usual theoretical abstraction, especially since not only was the extension of the palace beyond the square courtyard never realised, but nor does it seem it was even intended by Leonardo Valmarana, who bought up neighbouring properties rather than continuing the construction of the family palace. |

||

The palazzo was heavily damaged during the [[World War II]] by an Allied bombing on 18 March 1945. The roof, part of the [[attic]] and most of the main hall at the [[piano nobile]] were destroyed. The façade however remained intact, and today represents a rare example of a façade surviving with its original [[plaster]] and |

The palazzo was heavily damaged during the [[World War II]] by an Allied bombing on 18 March 1945. The roof, part of the [[attic]] and most of the main hall at the [[piano nobile]] were destroyed. The façade however remained intact, and today represents a rare example of a façade surviving with its original [[plaster]] and [[marmorino]]. In 1960, the ruined palace was sold by the Valmarana family to Vittor Luigi Braga Rosa, who led an extended restoration, rebuilding the parts demolished by war. He also enriched the palace with many decorations and artworks, coming from other destroyed palaces, in particular a collection of [[Seicento]] paintings by [[Giulio Carpioni]] with mythological themes. |

||

== Description == |

== Description == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The [[façade]] of the Palazzo Valmarana is both one of Palladio's most extraordinary and most individual realizations. For the first time in a palace, a [[giant order]] embraces the entire vertical expanse of the building: evidently this was a solution which found its origins in Palladio's experimentation with the façades of religious buildings, such as the almost contemporary façade of [[San Francesco della Vigna]]. Just as the [[nave]] and [[aisle]]s are projected onto the same plane in the [[Venice|Venetian]] church, so too on the façade of the Palazzo Valmarana the stratification of two systems becomes evident: the giant order of the six [[Composite order|Composite]] [[pilaster]]s seems to be superimposed on the minor order of [[Corinthian order|Corinthian]] pilasters,<ref name="TzonisLefaivre1986">{{cite book|author1=Alexander Tzonis|author2=Liane Lefaivre|title=Classical Architecture: The Poetics of Order|url=https:// |

The [[façade]] of the Palazzo Valmarana is both one of Palladio's most extraordinary and most individual realizations. For the first time in a palace, a [[giant order]] embraces the entire vertical expanse of the building: evidently this was a solution which found its origins in Palladio's experimentation with the façades of religious buildings, such as the almost contemporary façade of [[San Francesco della Vigna]]. Just as the [[nave]] and [[aisle]]s are projected onto the same plane in the [[Venice|Venetian]] church, so too on the façade of the Palazzo Valmarana the stratification of two systems becomes evident: the giant order of the six [[Composite order|Composite]] [[pilaster]]s seems to be superimposed on the minor order of [[Corinthian order|Corinthian]] pilasters,<ref name="TzonisLefaivre1986">{{cite book|author1=Alexander Tzonis|author2=Liane Lefaivre|title=Classical Architecture: The Poetics of Order|url=https://archive.org/details/classicalarchite00tzon_0|url-access=registration|date=1 January 1986|publisher=MIT Press|isbn=978-0-262-70031-3|page=[https://archive.org/details/classicalarchite00tzon_0/page/160 160]}}</ref> in a far more evident way at the edges where the absence of the final pilaster serves to reveal the underlying order which supports a [[bas-relief]] of a warrior who bears the Valmarana [[Coat of arms|arms]]. |

||

Rather than abstract geometrical constructions, the compositional logic of these civil and religious façades derived from Palladio’s familiarity with the techniques of draughting, in particular the [[orthogonal projection|orthogonal representation]]s by which he visualised projects and reconstructed antique buildings, and which moreover allowed him a punctilious control over the relationships between the building’s interior and exterior. |

Rather than abstract geometrical constructions, the compositional logic of these civil and religious façades derived from Palladio’s familiarity with the techniques of draughting, in particular the [[orthogonal projection|orthogonal representation]]s by which he visualised projects and reconstructed antique buildings, and which moreover allowed him a punctilious control over the relationships between the building’s interior and exterior. |

||

<gallery> |

<gallery mode="packed" heights="150px"> |

||

File:Palazzo Valmarana pianta B Scamozzi 1776.jpg|Floor plan ( |

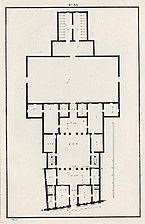

File:Palazzo Valmarana pianta B Scamozzi 1776.jpg|Floor plan (Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi, 1776) |

||

| ⚫ | |||

File:Palazzo Valmarana Vicenza 2009-07-25 f09.jpg|The loggia at the entrance, seen from the inner courtyard |

File:Palazzo Valmarana Vicenza 2009-07-25 f09.jpg|The loggia at the entrance, seen from the inner courtyard |

||

File:Palazzo Valmarana Vicenza 2009-07-25 f12.jpg|Detail of [[Ionic order| |

File:Palazzo Valmarana Vicenza 2009-07-25 f12.jpg|Detail of [[Ionic order|Ionic]] capitals in the loggia |

||

File:Palazzo Valmarana Vicenza salone 2009-07-25 f01.jpg|Detail of the only floor section of piano nobile hall survived to Allied bombing in 1945 |

File:Palazzo Valmarana Vicenza salone 2009-07-25 f01.jpg|Detail of the only floor section of piano nobile hall survived to Allied bombing in 1945 |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

== |

==See also== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{reflist}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Loggia Valmarana]] |

|||

== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

== |

==External links== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

== External links == |

|||

* [http://www.palazzovalmaranabraga.it/ Official site] |

* [http://www.palazzovalmaranabraga.it/ Official site] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{ |

{{Andrea Palladio}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Houses completed in 1565]] |

[[Category:Houses completed in 1565]] |

||

Latest revision as of 14:28, 25 July 2022

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Vicenza, Province of Vicenza, Veneto, Italy |

| Part of | City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i)(ii) |

| Reference | 712bis-001 |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) |

| Coordinates | 45°32′52″N 11°32′37″E / 45.54778°N 11.54361°E |

Palazzo Valmarana is a palace in Vicenza. It was built by Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio in 1565 for the noblewoman Isabella Nogarola Valmarana. Since 1994 it is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site "City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto".[1]

History[edit]

The foundation medal of this building bears engraved the date 1566 as well as the bust of Isabella Nogarola Valmarana, and it is the latter who signed the construction contracts with the builders in December 1565. Nevertheless, no doubts can remain about the role her deceased husband, Giovanni Alvise (died 1558), played in choosing Palladio as designer of his family palace. In 1549, along with Girolamo Chiericati and Giangiorgio Trissino, Giovanni Alvise Valmarana had publicly supported Palladio’s project for the porticoes of the Basilica Palladiana, evidently on the basis of an opinion formed six years prior, when Giovanni Alvise supervised the execution of ephemeral structures, conceived by Palladio under Trissino’s direction, to honour the entrance into Vicenza of Bishop Niccolò Ridolfi (1543). Furthermore, it was a space designed by Palladio – the Valmarana Chapel in the church of Santa Corona – which would eventually host the mortal remains of Giovanni Alvise and Isabella, on the commission of their son Leonardo.

On the site later occupied by the new 16th century (Cinquecento) palace, the Valmarana family possessed buildings right from the end of the 15th century (Quattrocento), which were progressively combined until they became the object of Palladio’s renovation. The planimetric irregularity of the internal spaces doubtless derives from the oblique orientation of the façade and of pre-existing walls. In this sense it becomes quite evident just how much the Olympian regularity of the palace illustrated in I quattro libri dell'architettura (1570) was the product of Palladio’s usual theoretical abstraction, especially since not only was the extension of the palace beyond the square courtyard never realised, but nor does it seem it was even intended by Leonardo Valmarana, who bought up neighbouring properties rather than continuing the construction of the family palace.

The palazzo was heavily damaged during the World War II by an Allied bombing on 18 March 1945. The roof, part of the attic and most of the main hall at the piano nobile were destroyed. The façade however remained intact, and today represents a rare example of a façade surviving with its original plaster and marmorino. In 1960, the ruined palace was sold by the Valmarana family to Vittor Luigi Braga Rosa, who led an extended restoration, rebuilding the parts demolished by war. He also enriched the palace with many decorations and artworks, coming from other destroyed palaces, in particular a collection of Seicento paintings by Giulio Carpioni with mythological themes.

Description[edit]

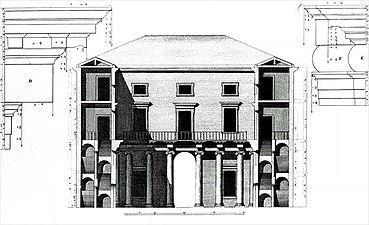

The façade of the Palazzo Valmarana is both one of Palladio's most extraordinary and most individual realizations. For the first time in a palace, a giant order embraces the entire vertical expanse of the building: evidently this was a solution which found its origins in Palladio's experimentation with the façades of religious buildings, such as the almost contemporary façade of San Francesco della Vigna. Just as the nave and aisles are projected onto the same plane in the Venetian church, so too on the façade of the Palazzo Valmarana the stratification of two systems becomes evident: the giant order of the six Composite pilasters seems to be superimposed on the minor order of Corinthian pilasters,[2] in a far more evident way at the edges where the absence of the final pilaster serves to reveal the underlying order which supports a bas-relief of a warrior who bears the Valmarana arms.

Rather than abstract geometrical constructions, the compositional logic of these civil and religious façades derived from Palladio’s familiarity with the techniques of draughting, in particular the orthogonal representations by which he visualised projects and reconstructed antique buildings, and which moreover allowed him a punctilious control over the relationships between the building’s interior and exterior.

-

Floor plan (Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi, 1776)

-

Cross section (Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi, 1776)

-

The loggia at the entrance, seen from the inner courtyard

-

Detail of Ionic capitals in the loggia

-

Detail of the only floor section of piano nobile hall survived to Allied bombing in 1945

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Forum Center - Comune Di Vicenza - Vicenza Città Unesco Archived 24 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alexander Tzonis; Liane Lefaivre (1 January 1986). Classical Architecture: The Poetics of Order. MIT Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-262-70031-3.