Platformism: Difference between revisions

Tightened up bibliography, further reading and external links |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Altered pages. Formatted dashes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Eastmain | Category:Platformism | #UCB_Category 2/2 |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Form of anarchist organization}} |

{{short description|Form of anarchist organization}} |

||

{{platformism sidebar|expanded=all}} |

{{platformism sidebar|expanded=all}} |

||

'''Platformism''' is an anarchist organizational theory that aims to create a tightly-coordinated anarchist federation. Its main features include a common [[Tactic (method)|tactical line]], a unified political [[policy]] and a commitment to [[collective responsibility]]. |

|||

'''Platformism''' is a form of [[anarchist]] organization that seeks unity from its participants, having as a defining characteristic the idea that each platformist organization should include only people that are fully in agreement with core group ideas, rejecting people who disagree. It stresses the need for tightly organized anarchist organizations that are able to influence working class and peasant movements.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secJ3.html#secj33 |title=J.3 What kinds of organisation do anarchists build? {{!}} Anarchist Writers |website=anarchism.pageabode.com |access-date=31 January 2019}}</ref> |

|||

First developed by [[Peter Arshinov]] in response to the perceived disorganization of the [[Anarchism in Russia|Russian anarchist movement]], platformism proposes that a "general union of anarchists" be established to agitate, educate and organize the [[working class]]es. It advocates [[entryism|working within]] existing [[Mass movement (politics)|mass organizations]], such as [[trade unions]], in order to transform them into vehicles for a [[social revolution]]. |

|||

Platformist groups reject the model of [[Leninism|Leninist]] [[vanguardism]], instead aiming to "make anarchist ideas the leading ideas within the [[class struggle]]".<ref name="WSM">{{cite web|author=Workers Solidarity Movement |date=2012 |url=http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/once/join.html |title=Why You Should Join the Workers Solidarity Movement |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170103053447/http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/once/join.html# |archive-date=3 January 2017 |access-date=5 January 2012}}</ref> According to platformism, the four main principles by which an anarchist organisation should operate are ideological unity, tactical unity, [[Collective action|collective responsibility]] and [[federalism]]. |

|||

== |

==History== |

||

===Precursors=== |

|||

In general, platformist groups aim to win the widest possible influence for anarchist ideas and methods in the working class and peasantry—like [[especifismo]] groups, platformists orient towards the working class, rather than to the rest of the [[far left]]. This usually entails a willingness to work in single-issue campaigns, and towards [[trade union]]s and community groups; and to fight for immediate reforms while linking this to a project of building popular consciousness and organisation. Since platformism grew from the lack of structure during an insurrection, they reject approaches that they believe will prevent this, such as [[insurrectionary anarchism]], as well as "views that dismiss activity in the unions" or that dismiss [[anti-imperialist]] movements.<ref name="Anarkismo statement">Anarkismo, 2012, [http://www.anarkismo.net/about_us "About Us"]. Retrieved 5 January 2012.</ref> |

|||

The roots of platformism go back as far as the organizational principles of [[Mikhail Bakunin]],{{Sfnm|1a1=Darch|1y=2020|1p=143|2a1=Graham|2y=2018|2p=330}} particularly in his theory of "organisational dualism". Bakunin proposed that anarchists form their own revolutionary organisations that would encourage workers to rebel against the state and capitalism, and once a [[social revolution]] had replaced the state with a federation of [[voluntary association]]s, it would then agitate against any attempted reconstitution of the state by political parties.{{Sfn|Graham|2018|pp=330-331}} |

|||

The Platform's most direct predecessor was the ''[[Draft Declaration of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine]]'', adopted in 1919 by the [[Military Revolutionary Council]] of the [[Makhnovshchina]]. The ''Draft Declaration'' called for a "[[Left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks|Third Revolution]]" against the Bolshevik government, in order to establish a regime of [[free soviets]].{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|pp=61-62}} It centred the [[Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine]] as the nucleus of this revolution, where the organization's entire membership would carry out the decision-making process.{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|pp=62-63}} In 1921, the Makhnovists published another ''Declaration'' that proclaimed a [[dictatorship of the proletariat]] in the form of an anarchist-led trade union system, for which [[Nestor Makhno]] himself was accused of [[Bonapartism]].{{Sfn|Darch|2020|p=75}} |

|||

The name derives from the 1926 ''Organisational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft)'',<ref name=Platformtext>{{cite book |last=''Dielo Truda'' group |author-link=Dielo Truda |title=Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft) |orig-year=1926 |url=http://www.nestormakhno.info/english/newplatform/organizational.htm |access-date=5 January 2012 |year=2006 |publisher=Nestor Makhno Archive |location=Ireland}}</ref> published by the Group of Russian Anarchists Abroad, in their journal ''[[Dielo Truda]]'' ("Workers' Cause"). The group, which consisted of exiled [[Anarchism in Russia|Russian anarchist]] veterans of the 1917 [[October Revolution]] (notably Ukrainian [[Nestor Makhno]] who played a leading role in the [[Makhnovshchina]] of 1918–1921), based the ''Platform'' on their experiences of the revolution and the eventual victory of the [[Bolsheviks]] over the anarchists and other groups during the [[left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks|left-wing uprisings against them]]. The ''Platform'' attempted to address and explain the anarchist movement's failures during the [[Russian Revolution (1917)|Russian Revolution]] outside Ukraine. The document drew praise and criticism from anarchists worldwide and sparked a major debate within the anarchist movement.{{Sfn|van der Walt|Schmidt|2009|pp=252-255}} |

|||

Meanwhile, the [[Nabat|Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations]], which had originally been established as a loose-knit organization, developed into a tightly-organized structure with a unified policy and an executive committee, in what a member would later describe as a precursor to platformism.{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|p=66}} |

|||

=== Organisational ideas === |

|||

The ''Platform'' describes four key organisational features which distinguish platformism: |

|||

* '''[[Tactic (method)|Tactical unity]]''' — "A common tactical line in the movement is of decisive importance for the existence of the organisation and the whole movement: it avoids the disastrous effect of several tactics opposing each other; it concentrates the forces of the movement; and gives them a common direction leading to a fixed objective".<ref>From section on Tactical Unity in [http://www.nestormakhno.info/english/platform/organizational.htm The Platform]</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Policy|Theoretical unity]]''' — "Theory represents the force which directs the activity of persons and organisations along a defined path towards a determined goal. Naturally it should be common to all the persons and organisations adhering to the General Union. All activity by the General Union, both overall and in its details, should be in perfect concord with the theoretical principles professed by the union".<ref>From section on theoretical unity in [http://www.nestormakhno.info/english/platform/organizational.htm The Platform]</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Collective responsibility]]''' — "The practice of acting on one's personal responsibility should be decisively condemned and rejected in the ranks of the anarchist movement. The areas of revolutionary life, social and political, are above all profoundly collective by nature. Social revolutionary activity in these areas cannot be based on the personal responsibility of individual militants".<ref>From section on Collective responsibility in [http://www.nestormakhno.info/english/platform/organizational.htm The Platform]</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Federalism]]''' — "Against centralism, anarchism has always professed and defended the principle of federalism, which reconciles the independence and initiative of individuals and the organisation with service to the common cause".<ref>All sourced from the [http://www.nestormakhno.info/english/platform/organizational.htm From section Federalism within the Organizational Section of the original document]</ref> |

|||

===Formulation=== |

|||

The ''Platform'' argues that "[w]e have vital need of an organisation which, having attracted most of the participants in the anarchist movement, would establish a common tactical and political line for anarchism and thereby serve as a guide for the whole movement". In short, unity means unity of ideas and actions as opposed to unity on the basis of the anarchist label. |

|||

[[File:Portrait_de_Piotr_Archinov.jpg|thumb|right|[[Peter Arshinov]], the main theoretician of the ''Platform''.]] |

|||

After their flight into exile, [[Anarchism in Russia|Russian]] and [[Anarchism in Ukraine|Ukrainian anarchists]] began to call for the reorganization of the anarchist movement, considering that chronic disorganization had led to their defeat during the [[Russian Revolution|Revolution]].{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1971|1pp=238-239|2a1=Darch|2y=2020|2p=140|3a1=Malet|3y=1982|3pp=163-164, 190|4a1=Schmidt|4y=2013|4p=60|5a1=Skirda|5y=2002|5p=120}} Among the anarcho-communists, [[Peter Arshinov]] was the most vocal advocate of reorganization.{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1971|1p=241|2a1=Skirda|2y=2002|2pp=122-123}} |

|||

On 20 June 1926, the ''Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft)'' was published in ''[[Delo Truda]]'', with an introduction penned by Arshinov.{{Sfnm|1a1=Darch|1y=2020|1p=143|2a1=Skirda|2y=2002|2p=122, 124}} Considering the goal of anarchism to be a [[social revolution]] that would create a [[stateless society|stateless]] and [[classless society]], the ''Platform'' proposed the establishment of a General Union of Anarchists to educate the [[working class]] and raise [[class consciousness]].{{Sfn|Darch|2020|pp=143-144}} This General Union was to be organised according to the principles of [[policy|theoretical unity]], [[Tactic (method)|tactical unity]] and [[collective responsibility]],{{Sfnm|1a1=Darch|1y=2020|1p=143|2a1=Schmidt|2y=2013|2p=61|3a1=Skirda|3y=2002|3pp=124-125}} and would be governed by an [[Committee#Executive committee|executive committee]] that coordinated collective action and political policy.{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1971|1p=241|2a1=Malet|2y=1982|2p=190|3a1=Schmidt|3y=2013|3p=61}} |

|||

== History == |

|||

The ''Organisational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft)'' was written in 1926 by the Group of Russian Anarchists Abroad, a group of exiled Russian and Ukrainian [[anarchists in France]] who published the ''Dielo Truda'' journal. The pamphlet is an analysis of basic anarchist beliefs, a vision of an anarchist society and recommendations as to how an anarchist organisation should be structured. |

|||

===Debate=== |

|||

=== Antecedents of the ''Platform'' === |

|||

The ''Platform'' was first presented at a meeting of the ''Delo Truda'' group, with attendees also including [[Anarchism in Bulgaria|Bulgarian]], [[Anarchism in China|Chinese]], [[Anarchism in France|French]] and [[Anarchism in Italy|Italian anarchists]]. At the meeting, Arshinov introduced the document as a way forward for the international anarchist movement to "marshal its forces".{{Sfn|Skirda|2002|p=124}} Although supported by [[Nestor Makhno]], Arshinov's ''Platform'' was opposed by most prominent anarchists at the time.{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1971|1pp=241-242|2a1=Darch|2y=2020|2p=144|3a1=Malet|3y=1982|3pp=163-164, 190-191}} [[Anarchism in France|French anarchists]] in attendance, led by [[Sebastien Faure]], criticised it as Russocentric, considering it unapplicable to the material conditions in France.{{Sfnm|1a1=Darch|1y=2020|1p=144|2a1=Skirda|2y=2002|2p=124}} In the years that followed, Faure's ''[[Synthesis anarchism|Anarchist Synthesis]]'', which rejected platformism in favor of a more loose-knit organization, contributed to dividing the anarchist movement into "synthesists" and "platformists".{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|p=63}} |

|||

The authors of the ''Platform'' insisted that its basic ideas were not new, but had a long anarchist pedigree. Platformism is not therefore a revision away from classical anarchism, or a new approach, but a "restatement" of existing positions.{{Sfn|van der Walt|Schmidt|2009|pp=252-255}} |

|||

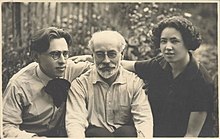

[[File:Fleshin-Voline-Steimer.jpg|thumb|right|[[Senya Fleshin]] (left), [[Volin]] (center), and [[Mollie Steimer]] (right), three of the ''Platform'''s main critics.]] |

|||

They cited [[Peter Kropotkin]] arguing that "the formation of an anarchist organisation in Russia, far from being prejudicial to the common revolutionary task, on the contrary it is desirable and useful to the very greatest degree" and argued that [[Mikhail Bakunin]]'s "aspirations concerning organisations, as well as his activity" in the [[First International]], "give us every right to view him as an active partisan of just such an organisation". Indeed, "practically all active anarchist militants fought against all dispersed activity, and desired an anarchist movement welded by unity of ends and means".<ref>From section on Tactical Unity in [http://www.nestormakhno.info/english/platform/introduction.htm The Platform]</ref> |

|||

The Platform's harshest critics included [[Volin]], [[Senya Fleshin]] and [[Mollie Steimer]],{{Sfn|Avrich|1971|pp=241-242}} who denounced the ''Platform'' as an attempt to create an anarchist [[political party]],{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1971|1pp=241-242|2a1=Darch|2y=2020|2p=144|3a1=Malet|3y=1982|3pp=190-191|4a1=Skirda|4y=2002|4pp=125-126}} which they feared would inevitably result in the formation of a [[police state]].{{Sfn|Avrich|1971|pp=241-242}} Arshinov responded by claiming his ''Platform'' actually abided by anarchist principles, as it consciously avoided [[coercion]] and preserved [[decentralization]].{{Sfn|Avrich|1971|pp=242-243}} The debate also took a more personal turn as Makhno and Arshinov attacked Volin, which attracted denunciations from other critics of the ''Platform'',{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1971|1pp=242-243|2a1=Malet|2y=1982|2pp=190-191}} including [[Alexander Berkman]], who denounced Makhno as a [[militarism|militarist]] and Arshinov as a [[Bolsheviks|Bolshevik]].{{Sfn|Avrich|1971|pp=242-243}} |

|||

After years of defending the ideas of Platformism, in the early 1930s, Arshinov joined the [[Communist Party of the Soviet Union|Communist Party]] and defected to the [[Soviet Union]],{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1971|1pp=243|2a1=Darch|2y=2020|2p=145|3a1=Malet|3y=1982|3pp=163-164, 191}} where he would disappear during the [[Great Purge]].{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1971|1pp=245-246|2a1=Darch|2y=2020|2p=145|3a1=Malet|3y=1982|3pp=163-164}} Nestor Makhno himself died in 1934, leaving the ''Platform'' without any prominent defenders.{{Sfnm|1a1=Darch|1y=2020|1p=145|2a1=Malet|2y=1982|2pp=164, 191-192}} Nevertheless, both the opponents and remaining supporters of the ''Platform'' managed to reconcile at Makhno's funeral.{{Sfn|Malet|1982|p=164}} Volin himself took up the publication of Makhno's memoirs, which were published in the years after his death.{{Sfn|Malet|1982|p=190}} |

|||

=== Problems caused by poor translations === |

|||

In his book ''Facing the Enemy'', [[Alexandre Skirda]] attributes much of the controversy about the ''Platform'' to the original 1926 French translation made by its opponent [[Volin]].{{Sfn|Skirda|2002|p=131}} Later translations to French have corrected some of the mistranslations and the latest English translation, made directly from the Russian original, reflects this.{{Sfn|Skirda|2002|pp=186-187}} |

|||

=== |

===Organizational developments=== |

||

During the [[Spanish Revolution of 1936]], a number of revolutionary anarchist hard-liners formed the [[Friends of Durruti Group]] in opposition to the state's [[militarisation]] of the [[confederal militias]].{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|pp=80-81}} After the Revolution was [[May Days|suppressed]], the group published ''Towards a Fresh Revolution'', which called for a revolutionary council to reform the militias and bring the economy back under the control of the [[Confederación Nacional del Trabajo]] (CNT), which would effectively have dissolved the [[government of Spain]].{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|p=81}} In the wake of the [[1944 Bulgarian coup d'état]], the Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria (FAKB) issued its own ''Platform'', which argued for a specifically anarcho-communist federation, coordinated by a central secretariat, which would participate in trade unions and prepare for a social revolution.{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|pp=82-84}} |

|||

Some platformist organisations today are unhappy with the designation, often preferring to use descriptions such as "anarchist communist", "social anarchist", "libertarian communist/socialist" or even [[especifist]]. Most agree that the 1926 ''Platform'' was sorely lacking in certain areas and point out that it was a draft document, never intended to be adopted in its original form. The Italian [[Federation of Anarchist Communists]] (FdCA), for example, do not insist on the principle of "tactical unity", which according to them is impossible to achieve over a large area, preferring instead "tactical homogeneity".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fdca.it/fdcaen/organization/tesi.htm |title=FdCA positions and theoretical documents |access-date=2 January 2012}}</ref> |

|||

In 1953, the French anarchist [[Georges Fontenis]] published his ''Manifesto of Libertarian Communism'', which attacked the prevailing synthesist orientation of the French anarchist movement, becoming the founding document for the Libertarian Communist Federation (FCL).{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|pp=94-95}} Drawing from aspects of the ''Platform'', Fontenis' ''Manifesto'' called for an anarchist [[vanguardism|revolutionary vanguard]] to work within existing mass organizations in order to develop a [[Mass movement (politics)|mass movement]], with the eventual aim of dissolving itself into the movement and achieving a social revolution.{{Sfnm|1a1=Schmidt|1y=2013|1pp=95-96|2a1=Skirda|2y=2002|2pp=171-172}} In the years that followed, the FCL united together with the North African Libertarian Movement (MLNA) to establish the Libertarian Communist International (ICL), but their suppression by the French state forced the organization's dissolution in 1957.{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|p=96}} Platformism was revived in France during the events of [[May 68]], when the [[Revolutionary Anarchist Organization]] (ORA) was founded, although it would remain the minority tendency within the anarchist movement.{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|pp=96-97}} The formation of the ORA accelerated the establishment of other anarchist federations throughout Europe, such as the [[Anarchist Federation (Britain)|Anarchist Federation]] (AF) in Britain and the Federation of Anarchist Communists (FdCA) in Italy, while the ORA itself would eventually be succeeded by the [[Union communiste libertaire|Libertarian Communist Union]] (UCL).{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|pp=97-98}} |

|||

=== Especifismo === |

|||

'''Especifismo''' ({{IPA-pt|eʃpesiˈfiʒmu|lang}}, "specifism") is one of the two main forms of [[activism]] championed by [[Federação Anarquista do Rio de Janeiro]] (FARJ) and other [[South America]]n anarchist organizations, the other being [[social insertion]]. Especifismo emerged as a result of Anarchist experiences in South America over the latter half of the 20th century starting with the [[Federación Anarquista Uruguaya]] (FAU), which was founded in 1956 by Anarchists who saw the need for an [[organization]] which was specifically Anarchist. Especifismo has been summarized as: |

|||

''Especifismo'' ({{Lang-en|Specifism}}) was first developed in 1972 by the [[Uruguayan Anarchist Federation]] (FAU), with the publication of its text ''Huerta Grande'', which proposed the creation of a unified political policy directly applicable to the material conditions in Uruguay.{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|p=98}} The collapse of the ruling [[right-wing dictatorship]]s towards the end of the [[Cold War]] resulted in the emergence of many other ''especifista'' groups throughout Latin America, in a process spearheaded by the FAU.{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|p=102}} In 2003, the [https://Anarkismo.net Anarkismo.net] website was established by an international network of anarcho-communist organizations, including both Latin American ''especifistas'' and European platformists, which publishes news and analysis in a variety of different languages.{{Sfn|Schmidt|2013|p=105}} |

|||

*The need for a specifically Anarchist organization built around a unity of ideas and [[Praxis (process)|praxis]]. |

|||

*The use of the specifically Anarchist organization to theorize and develop strategic political and organizing work. |

|||

*Active involvement in and building of [[autonomous]] and popular [[social movements]] via social insertion.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Adam|first=Weaver|title=Especifismo: The anarchist praxis of building popular movements and revolutionary organization in South America|url=https://libcom.org/library/especifismo-anarchist-praxis-building-popular-movements-revolutionary-organization-south|website=Libcom}}</ref> |

|||

== Criticism == |

|||

The ''Platform'' attracted strong criticism from some sectors on the anarchist movement of the time, including some of the most influential anarchists such as [[Volin]], [[Errico Malatesta]], [[Luigi Fabbri]], [[Camillo Berneri]], [[Max Nettlau]], and [[Alexander Berkman]], [[Emma Goldman]] and [[Grigorii Maksimov]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.infoshop.org/AnarchistFAQSectionJ3#secj34|title=Why do many anarchists oppose the "Platform"?|publisher=[[An Anarchist FAQ]]|access-date=Aug 12, 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131004212653/http://www.infoshop.org/AnarchistFAQSectionJ3#secj34|archive-date=2013-10-04}}</ref> |

|||

=== Synthesist alternative === |

|||

As an alternative to platformism [[Volin]] and [[Sébastien Faure]] proposed [[Synthesis anarchism|synthesist anarchist]] federations.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.anarkismo.net/article/15329|title=Especifismo and Synthesis/ Synthesism|access-date=4 May 2015}}</ref> In place of the ''Platform's'' stress on tight political and organisational unity, the "synthesist" approach argued for a far looser organization that would maximise numbers i.e. a [[big tent]] approach. Platformists view such organisations as weak despite their numbers as the lack of common views means an inability to undertake common actions—defeating the purpose of a common organisation.{{Sfn|van der Walt|Schmidt|2009|pp=252-255}} |

|||

=== Errico Malatesta's views === |

|||

While such criticisms indicated a direct rejection of the ''Platform's'' proposals, others seem to have arisen from misunderstandings. |

|||

Notably, Malatesta initially believed that the ''Platform'' was "typically authoritarian" and "far from helping to bring about the victory of anarchist communism, to which they aspire, could only falsify the anarchist spirit and lead to consequences that go against their intentions".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/platform/malatesta_project.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/19980416051823/http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/platform/malatesta_project.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=16 April 1998|title=A Project of Anarchist Organisation|access-date=4 May 2015}}</ref> |

|||

However, after further correspondence with Makhno—and after seeing a platformist group in formation—Malatesta concluded that he was actually in agreement with the positions of the ''Platform'', but had been confused by the language they had used: |

|||

<blockquote>But all this is perhaps only a question of words.<br><br>In my reply to Makhno I already said: "It may be that, by the term collective responsibility, you mean the agreement and solidarity that must exist among the members of an association. And if that is so, your expression would, in my opinion, amount to an improper use of language, and therefore, being only a question of words, we would be closer to understanding each other."<br><br>And now, reading what the comrades of the 18e say, I find myself more or less in agreement with their way of conceiving the anarchist organisation (being very far from the authoritarian spirit which the "Platform" seemed to reveal) and I confirm my belief that behind the linguistic differences really lie identical positions.<ref>Malatesta, On Collective Responsibility, http://www.nestormakhno.info/english/mal_rep3.htm</ref></blockquote> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[Especifismo]] |

|||

* [[Federalism]] |

|||

* [[Synthesis anarchism]], [[Volin]]'s and [[Sébastien Faure]]´s response to platformism |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

| Line 64: | Line 39: | ||

== Bibliography == |

== Bibliography == |

||

{{refbegin|2}} |

{{refbegin|2}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Avrich|first=Paul|author-link=Paul Avrich|title=[[The Russian Anarchists]]|year=1971|orig-year=1967|location=[[Princeton, New Jersey|Princeton]]|publisher=[[Princeton University Press]]|isbn=0-691-00766-7|oclc=1154930946 |

* {{cite book|last=Avrich|first=Paul|author-link=Paul Avrich|title=[[The Russian Anarchists]]|year=1971|orig-year=1967|location=[[Princeton, New Jersey|Princeton]]|publisher=[[Princeton University Press]]|isbn=0-691-00766-7|oclc=1154930946}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{Cite book |last1=Baker |first1=Zoe |chapter=Organizational Dualism: From Bakunin to the Platform |title=Means and Ends: The Revolutionary Practice of Anarchism in Europe and the United States |date=2023 |isbn=978-1-84935-498-1 |publisher=[[AK Press]] |oclc=1345217229 |df=mdy-all |pages=307–346}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Berry|first=David|year=2002|title=A History of the French Anarchist Movement: 1917 to 1945|location=[[Westport, CT]]|publisher=[[Greenwood Press]]|lccn=2001054702|isbn=0-313-32026-8|issn=0885-9159}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{cite book|title= |

* {{cite book |last=Darch|first=Colin|title=Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917-1921|year=2020|location=[[London]]|publisher=[[Pluto Press]]|isbn=9781786805263|oclc=1225942343}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Graham|first=Robert|chapter=Anarchism and the First International|editor-last1=Adams|editor-first1=Matthew S.|editor-last2=Levy|editor-first2=Carl|year=2018|title=The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism|location=London|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|isbn=978-3319756196|pages=325–342|doi=10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_19|s2cid=158605651 }} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{cite book|title=Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism|first=Michael|last=Schmidt|year=2013|location=[[Edinburgh]]|publisher=[[AK Press]]|orig-year=2012|isbn=978-1849351386|oclc=881111188}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Facing the enemy: A history of anarchist organisation|last=Skirda|first=Alexandre|author-link=Alexandre Skirda|translator-last1=Sharkey|translator-first1=Paul|year=2002|publisher=[[AK Press]] |location=[[Oakland, California|Oakland]]|isbn=1902593197|oclc=490977034}} |

* {{cite book|title=Facing the enemy: A history of anarchist organisation|last=Skirda|first=Alexandre|author-link=Alexandre Skirda|translator-last1=Sharkey|translator-first1=Paul|year=2002|publisher=[[AK Press]] |location=[[Oakland, California|Oakland]]|isbn=1902593197|oclc=490977034}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Skirda |first1=Alexandre |author-link=Alexandre Skirda |translator-last1=Sharkey |translator-first1=Paul |title=Nestor Makhno–Anarchy's Cossack: The Struggle for Free Soviets in the Ukraine 1917–1921 |date=2004 |orig-year=1982 |language=en |isbn=978-1-902593-68-5 |publisher=[[AK Press]] |location=[[Oakland, California|Oakland]] |df=mdy-all |oclc=60602979 |pages=274–290}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Skirda |first1=Alexandre |author-link=Alexandre Skirda |translator-last1=Sharkey |translator-first1=Paul |title=Nestor Makhno–Anarchy's Cossack: The Struggle for Free Soviets in the Ukraine 1917–1921 |date=2004 |orig-year=1982 |language=en |isbn=978-1-902593-68-5 |publisher=[[AK Press]] |location=[[Oakland, California|Oakland]] |df=mdy-all |oclc=60602979 |pages=274–290}} |

||

Latest revision as of 21:39, 20 January 2024

| Part of a series on |

| Platformism |

|---|

|

Platformism is an anarchist organizational theory that aims to create a tightly-coordinated anarchist federation. Its main features include a common tactical line, a unified political policy and a commitment to collective responsibility.

First developed by Peter Arshinov in response to the perceived disorganization of the Russian anarchist movement, platformism proposes that a "general union of anarchists" be established to agitate, educate and organize the working classes. It advocates working within existing mass organizations, such as trade unions, in order to transform them into vehicles for a social revolution.

History[edit]

Precursors[edit]

The roots of platformism go back as far as the organizational principles of Mikhail Bakunin,[1] particularly in his theory of "organisational dualism". Bakunin proposed that anarchists form their own revolutionary organisations that would encourage workers to rebel against the state and capitalism, and once a social revolution had replaced the state with a federation of voluntary associations, it would then agitate against any attempted reconstitution of the state by political parties.[2]

The Platform's most direct predecessor was the Draft Declaration of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, adopted in 1919 by the Military Revolutionary Council of the Makhnovshchina. The Draft Declaration called for a "Third Revolution" against the Bolshevik government, in order to establish a regime of free soviets.[3] It centred the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine as the nucleus of this revolution, where the organization's entire membership would carry out the decision-making process.[4] In 1921, the Makhnovists published another Declaration that proclaimed a dictatorship of the proletariat in the form of an anarchist-led trade union system, for which Nestor Makhno himself was accused of Bonapartism.[5]

Meanwhile, the Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations, which had originally been established as a loose-knit organization, developed into a tightly-organized structure with a unified policy and an executive committee, in what a member would later describe as a precursor to platformism.[6]

Formulation[edit]

After their flight into exile, Russian and Ukrainian anarchists began to call for the reorganization of the anarchist movement, considering that chronic disorganization had led to their defeat during the Revolution.[7] Among the anarcho-communists, Peter Arshinov was the most vocal advocate of reorganization.[8]

On 20 June 1926, the Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft) was published in Delo Truda, with an introduction penned by Arshinov.[9] Considering the goal of anarchism to be a social revolution that would create a stateless and classless society, the Platform proposed the establishment of a General Union of Anarchists to educate the working class and raise class consciousness.[10] This General Union was to be organised according to the principles of theoretical unity, tactical unity and collective responsibility,[11] and would be governed by an executive committee that coordinated collective action and political policy.[12]

Debate[edit]

The Platform was first presented at a meeting of the Delo Truda group, with attendees also including Bulgarian, Chinese, French and Italian anarchists. At the meeting, Arshinov introduced the document as a way forward for the international anarchist movement to "marshal its forces".[13] Although supported by Nestor Makhno, Arshinov's Platform was opposed by most prominent anarchists at the time.[14] French anarchists in attendance, led by Sebastien Faure, criticised it as Russocentric, considering it unapplicable to the material conditions in France.[15] In the years that followed, Faure's Anarchist Synthesis, which rejected platformism in favor of a more loose-knit organization, contributed to dividing the anarchist movement into "synthesists" and "platformists".[16]

The Platform's harshest critics included Volin, Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer,[17] who denounced the Platform as an attempt to create an anarchist political party,[18] which they feared would inevitably result in the formation of a police state.[17] Arshinov responded by claiming his Platform actually abided by anarchist principles, as it consciously avoided coercion and preserved decentralization.[19] The debate also took a more personal turn as Makhno and Arshinov attacked Volin, which attracted denunciations from other critics of the Platform,[20] including Alexander Berkman, who denounced Makhno as a militarist and Arshinov as a Bolshevik.[19]

After years of defending the ideas of Platformism, in the early 1930s, Arshinov joined the Communist Party and defected to the Soviet Union,[21] where he would disappear during the Great Purge.[22] Nestor Makhno himself died in 1934, leaving the Platform without any prominent defenders.[23] Nevertheless, both the opponents and remaining supporters of the Platform managed to reconcile at Makhno's funeral.[24] Volin himself took up the publication of Makhno's memoirs, which were published in the years after his death.[25]

Organizational developments[edit]

During the Spanish Revolution of 1936, a number of revolutionary anarchist hard-liners formed the Friends of Durruti Group in opposition to the state's militarisation of the confederal militias.[26] After the Revolution was suppressed, the group published Towards a Fresh Revolution, which called for a revolutionary council to reform the militias and bring the economy back under the control of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), which would effectively have dissolved the government of Spain.[27] In the wake of the 1944 Bulgarian coup d'état, the Federation of Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria (FAKB) issued its own Platform, which argued for a specifically anarcho-communist federation, coordinated by a central secretariat, which would participate in trade unions and prepare for a social revolution.[28]

In 1953, the French anarchist Georges Fontenis published his Manifesto of Libertarian Communism, which attacked the prevailing synthesist orientation of the French anarchist movement, becoming the founding document for the Libertarian Communist Federation (FCL).[29] Drawing from aspects of the Platform, Fontenis' Manifesto called for an anarchist revolutionary vanguard to work within existing mass organizations in order to develop a mass movement, with the eventual aim of dissolving itself into the movement and achieving a social revolution.[30] In the years that followed, the FCL united together with the North African Libertarian Movement (MLNA) to establish the Libertarian Communist International (ICL), but their suppression by the French state forced the organization's dissolution in 1957.[31] Platformism was revived in France during the events of May 68, when the Revolutionary Anarchist Organization (ORA) was founded, although it would remain the minority tendency within the anarchist movement.[32] The formation of the ORA accelerated the establishment of other anarchist federations throughout Europe, such as the Anarchist Federation (AF) in Britain and the Federation of Anarchist Communists (FdCA) in Italy, while the ORA itself would eventually be succeeded by the Libertarian Communist Union (UCL).[33]

Especifismo (English: Specifism) was first developed in 1972 by the Uruguayan Anarchist Federation (FAU), with the publication of its text Huerta Grande, which proposed the creation of a unified political policy directly applicable to the material conditions in Uruguay.[34] The collapse of the ruling right-wing dictatorships towards the end of the Cold War resulted in the emergence of many other especifista groups throughout Latin America, in a process spearheaded by the FAU.[35] In 2003, the Anarkismo.net website was established by an international network of anarcho-communist organizations, including both Latin American especifistas and European platformists, which publishes news and analysis in a variety of different languages.[36]

References[edit]

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 143; Graham 2018, p. 330.

- ^ Graham 2018, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 75.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, p. 66.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 238–239; Darch 2020, p. 140; Malet 1982, pp. 163–164, 190; Schmidt 2013, p. 60; Skirda 2002, p. 120.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 241; Skirda 2002, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 143; Skirda 2002, p. 122, 124.

- ^ Darch 2020, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 143; Schmidt 2013, p. 61; Skirda 2002, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 241; Malet 1982, p. 190; Schmidt 2013, p. 61.

- ^ Skirda 2002, p. 124.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 241–242; Darch 2020, p. 144; Malet 1982, pp. 163–164, 190–191.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 144; Skirda 2002, p. 124.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, p. 63.

- ^ a b Avrich 1971, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 241–242; Darch 2020, p. 144; Malet 1982, pp. 190–191; Skirda 2002, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Avrich 1971, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 242–243; Malet 1982, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 243; Darch 2020, p. 145; Malet 1982, pp. 163–164, 191.

- ^ Avrich 1971, pp. 245–246; Darch 2020, p. 145; Malet 1982, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Darch 2020, p. 145; Malet 1982, pp. 164, 191–192.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 164.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 190.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, p. 81.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 95–96; Skirda 2002, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, p. 96.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, p. 98.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, p. 102.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, p. 105.

Bibliography[edit]

- Avrich, Paul (1971) [1967]. The Russian Anarchists. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00766-7. OCLC 1154930946.

- Baker, Zoe (2023). "Organizational Dualism: From Bakunin to the Platform". Means and Ends: The Revolutionary Practice of Anarchism in Europe and the United States. AK Press. pp. 307–346. ISBN 978-1-84935-498-1. OCLC 1345217229.

- Berry, David (2002). A History of the French Anarchist Movement: 1917 to 1945. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32026-8. ISSN 0885-9159. LCCN 2001054702.

- Darch, Colin (2020). Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917-1921. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 9781786805263. OCLC 1225942343.

- Graham, Robert (2018). "Anarchism and the First International". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 325–342. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_19. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158605651.

- Malet, Michael (1982). Nestor Makhno in the Russian Civil War. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-25969-6. OCLC 8514426.

- Schmidt, Michael (2013) [2012]. Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1849351386. OCLC 881111188.

- Skirda, Alexandre (2002). Facing the enemy: A history of anarchist organisation. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Oakland: AK Press. ISBN 1902593197. OCLC 490977034.

- Skirda, Alexandre (2004) [1982]. Nestor Makhno–Anarchy's Cossack: The Struggle for Free Soviets in the Ukraine 1917–1921. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Oakland: AK Press. pp. 274–290. ISBN 978-1-902593-68-5. OCLC 60602979.

- van der Walt, Lucien; Schmidt, Michael (2009). "Militant Minority: The Question of Anarchist Political Organisation". Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism. Edinburgh: AK Press. pp. 239–270. ISBN 978-1-904859-16-1. LCCN 2006933558. OCLC 1100238201.

Further reading[edit]

- Arshinov, Peter; Makhno, Nestor; Mett, Ida; et al. (2006) [1926]. The Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists. Translated by McNab, Nestor. Delo Truda – via The Nestor Makhno Archive.

- Balius, Jaime (1978) [1938]. Towards a Fresh Revolution. Friends of Durruti Group – via The Anarchist Library.

- Fontenis, Georges (1953). Manifesto of Libertarian Communism. Libertarian Communist Federation – via The Anarchist Library.

- Makhno, Nestor; Malatesta, Errico (1927–1930). About the Platform. Translated by McNab, Nestor – via The Anarchist Library.

External links[edit]

- Anarkismo.net - Multilingual anarchist news site run by over 30 platformist and especifist organisations on five continents