Joel Elias Spingarn: Difference between revisions

Retitled section headings; changed wikilink |

No edit summary |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 20 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American civil rights activist (1875–1939)}} |

|||

{{Infobox |

{{Infobox officeholder |

||

| honorific_prefix = |

|||

| |

|name = Joel Spingarn |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| honorific_suffix = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| |

|term_start = 1930 |

||

| |

|term_end = 1939 |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| caption = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

|office1 = Chair of the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|term_start1 = 1914 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|term_end1 = 1919 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|predecessor1 = [[Oswald Garrison Villard]] |

|||

| death_cause = |

|||

|successor1 = [[Mary White Ovington]] |

|||

| resting_place = |

|||

|birth_name = Joel Elias Spingarn |

|||

| resting_place_coordinates = <!-- {{coord|LAT|LONG|type:landmark|display=inline}} --> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| monuments = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| residence = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| nationality = [[Americans|American]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| citizenship = |

|||

|party = [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] (before 1912)<br>[[Progressive Party (United States, 1912–1920)|Progressive]] (1912–1916) |

|||

| education = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| alma_mater = [[Columbia College of Columbia University|Columbia College]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| occupation = educator, literary critic, civil rights activist |

|||

|relatives = [[Arthur B. Spingarn]] (brother) |

|||

| years_active = |

|||

|education = [[Columbia University]] ([[Bachelor of Arts|BA]]) |

|||

| employer = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| agent = |

|||

| known_for = |

|||

| notable_works = |

|||

| style = |

|||

| home_town = |

|||

| height = <!-- {{height|cm=X}} OR {{height|ft=X|in=Y}}--> |

|||

| weight = <!-- {{convert|X|kg|lb|0|abbr=on}} or {{convert|X|lb|kg|0|abbr=on}} --> |

|||

| title = |

|||

| term = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| successor = |

|||

| party = [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] |

|||

| movement = [[Civil rights movement (1896–1954)|Civil Rights Movement]] |

|||

| opponents = |

|||

| boards = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| parents = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Joel Elias Spingarn''' (May 17, 1875 – July 26, 1939) was an American [[educator]], [[literary critic]], |

'''Joel Elias Spingarn''' (May 17, 1875 – July 26, 1939) was an American [[educator]], [[literary critic]], [[Civil rights movement (1896–1954)|civil rights]] [[activist]], [[military intelligence]] officer, and [[horticulturalist]]. |

||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

| Line 51: | Line 31: | ||

Politics was one of his lifetime passions. In 1908, as a [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] he ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the [[U.S. House of Representatives]]. In 1912 and 1916, he was a delegate to the national convention of the [[Progressive Party (United States, 1912)|Progressive Party]]. At the first of those conventions, he failed in his attempts to add a statement condemning [[racial discrimination]] to the party platform. |

Politics was one of his lifetime passions. In 1908, as a [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] he ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the [[U.S. House of Representatives]]. In 1912 and 1916, he was a delegate to the national convention of the [[Progressive Party (United States, 1912)|Progressive Party]]. At the first of those conventions, he failed in his attempts to add a statement condemning [[racial discrimination]] to the party platform. |

||

He served as [[professor]] of [[comparative literature]] at [[Columbia University]] from 1899 to 1911. His academic publishing established him as one of America's foremost comparativists. It included two editions of ''A History of Literary Criticism in the Renaissance'' in 1899 and 1908 as well as edited works like ''Critical Essays of the Seventeenth-Century'' in 3 volumes. He summarized his philosophy in ''The New Criticism: A Lecture Delivered at Columbia University, March 9, 1910''.<ref>(NY: Columbia University Press, 1911)</ref> There he argued against the constraints of such traditional categories as genre, theme, and historical setting in favor of viewing each work of art afresh and on its own terms.<ref>Marvin A. Carlson, ''Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present'' (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984, 311-2</ref> |

He served as [[professor]] of [[comparative literature]] at [[Columbia University]] from 1899 to 1911. His academic publishing established him as one of America's foremost comparativists. It included two editions of ''A History of Literary Criticism in the Renaissance'' in 1899 and 1908 as well as edited works like ''Critical Essays of the Seventeenth-Century'' in 3 volumes. He summarized his philosophy in ''The New Criticism: A Lecture Delivered at Columbia University, March 9, 1910''.<ref>(NY: Columbia University Press, 1911)</ref> There he argued against the constraints of such traditional categories as genre, theme, and historical setting in favor of viewing each work of art afresh and on its own terms.<ref>Marvin A. Carlson, ''Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present'' (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984, 311-2</ref> Spingarn's criticism and aesthetical thought was deeply influenced by the Italian philosopher [[Benedetto Croce]], with whom he was in correspondence since 1899. Croce had Spingarn's masterwork translated in Italian (''La critica letteraria nel Rinascimento. Saggio sulle origini dello spirito classico nella letteratura moderna'', trad. di Antonio Fusco, pref. di B. Croce, Laterza, Bari 1905). Their correspondence was published in Naples in 2001 (''Carteggio Croce-Spingarn'', a cura di Emanuele Cutinelli-Rendina, Istituto italiano per gli studi storici, Napoli, 2001). |

||

From 1904, his role in academic politics marked him as an independent spirit—too independent for the university's autocratic president [[Nicholas Murray Butler]]. His differences with the administration ranged from personality conflicts to educational philosophy. Things came to a head in 1910, when he offered a resolution at a university faculty meeting in support of [[Harry Thurston Peck]], a Columbia professor who had been summarily dismissed by Butler because of a public scandal involving a breach-of-promise suit. That precipitated Spingarn's dismissal just five weeks later.<ref>Michael, Rosenthal, ''Nicholas Miraculous: The Amazing Career of the Redoubtable Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler'' (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 209ff.</ref> He became part of a distinguished series of prominent academics who resigned or were dismissed during Butler's tenure as president, including [[George Edward Woodberry]], [[Charles A. Beard|Charles Beard]], and [[James Harvey Robinson]]. |

From 1904, his role in academic politics marked him as an independent spirit—too independent for the university's autocratic president [[Nicholas Murray Butler]]. His differences with the administration ranged from personality conflicts to educational philosophy. Things came to a head in 1910, when he offered a resolution at a university faculty meeting in support of [[Harry Thurston Peck]], a Columbia professor who had been summarily dismissed by Butler because of a public scandal involving a breach-of-promise suit. That precipitated Spingarn's dismissal just five weeks later.<ref>Michael, Rosenthal, ''Nicholas Miraculous: The Amazing Career of the Redoubtable Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler'' (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 209ff.</ref> He became part of a distinguished series of prominent academics who resigned or were dismissed during Butler's tenure as president, including [[George Edward Woodberry]], [[Charles A. Beard|Charles Beard]], and [[James Harvey Robinson]]—all of them, like Peck and Spingarn, notable progressive scholars. |

||

Without an academic appointment but of independent means, Spingarn continued to publish in his field much as he had before, writing, editing, and contributing to collections of essays. He was commissioned in the [[U.S. Army]] and served as a [[major]] during [[World War I]].<ref> |

Without an academic appointment but of independent means, Spingarn continued to publish in his field much as he had before, writing, editing, and contributing to collections of essays. He was commissioned in the [[U.S. Army]] and served as a [[Major (rank)|major]] during [[World War I]].<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.nndb.com/people/466/000114124/ |title = profile of Joel Elias Spingarn|work=[[NNDB]]}}</ref> In 1919 he was a co-founder of the publishing firm of [[Harcourt Trade Publishers|Harcourt, Brace and Company]]. |

||

He also took up the other cause of his life, racial justice. An influential [[American liberalism|liberal]] Republican, he helped realize the concept of a unified black movement by joining the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP) shortly after its founding and was one of the first Jewish leaders of that organization, serving as chairman of its board from 1913 to 1919, its treasurer from 1919 to 1930, its second president from 1930 until his death in 1939. |

He also took up the other cause of his life, racial justice. An influential [[American liberalism|liberal]] Republican, he helped realize the concept of a unified black movement by joining the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP) shortly after its founding and was one of the first Jewish leaders of that organization, serving as chairman of its board from 1913 to 1919, its treasurer from 1919 to 1930, its second president from 1930 until his death in 1939. |

||

In 1914 he established the [[Spingarn Medal]], awarded annually by the NAACP for outstanding achievement by an [[African American]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Always interested in [[gardening]], in the years following 1920 he amassed the world's largest collection of [[clematis]]—250 species—and published the results of his research on the early history of [[landscape gardening]] and [[horticulture]] in [[Dutchess County, New York]].<ref>New York Botanical Garden: [http://library.nybg.org/finding_guide/archv/spingarn_ppb.html Joel Elias Spingarn Papers]</ref> He served as a member of the Board of Managers for the [[New York Botanical Garden]].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://library.nybg.org/finding_guide/archv/spingarn_ppb.html|title= Joel Elias Spingarn Papers (PP)|publisher |

||

During World War I, according to an NAACP publication, he was instrumental in seeing that "a training camp for Negro officers at [[Des Moines]] was established and about 1,000 Negro officers commissioned."<ref>''The Crisis'': [https://books.google.com/books?id=NlsEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA269 "President Spingarn Dies,"] Sept., 1939</ref> Spingarn also served as an intelligence officer on the [[Military Intelligence Board]] (MIB), and provided information to the government about the NAACP's membership, which had been accused of having [[Communism|Communist]] influences.<ref>{{Cite thesis|title='Negro subversion' : the investigation of black unrest and radicalism by agencies of the United States government, 1917-1920|url=https://abdn.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/delivery/44ABE_INST:44ABE_VU1/12152872610005941|publisher=University of Aberdeen|date=1984|degree=Ph.D.|first=Christopher M. D.|last=Ellis}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Cockburn|first=Alexander|date=1993-04-13|title=When the State Is Terrified, Citizens Beware : A Memphis reporter writing about Dr. King uncovers decades of Army spying on Americans.|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-04-13-me-22238-story.html|access-date=2021-12-22|website=Los Angeles Times|language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

[[W. E. B. Du Bois]] (who had been unsuccessfully recommended by Spingarn for the MIB<ref name="Lewis Biography">{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=David Levering |authorlink = David Levering Lewis |title=W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868–1919 |date=1994 |publisher=Henry Holt and Company |isbn=9780805035681 |pages=553–560 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iiDvQoVhoq0C |access-date=November 27, 2022}}</ref>) dedicated his 1940 autobiography ''[[Dusk of Dawn]]'' to Spingarn's memory, calling him "scholar and knight."<ref name="Lewis Fight">{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=David Levering |title=W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919–1963 |date=2001 |publisher=Henry Holt and Company |isbn=9780805068139 |page=472 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RD75BE1Alr4C&q=w.+e.+b.+du+bois:+the+fight+for+equality+and+the+american+century+1919%E2%80%931963 |access-date=November 27, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Always interested in [[gardening]], in the years following 1920 he amassed the world's largest collection of [[clematis]]—250 species—and published the results of his research on the early history of [[landscape gardening]] and [[horticulture]] in [[Dutchess County, New York]].<ref>New York Botanical Garden: [http://library.nybg.org/finding_guide/archv/spingarn_ppb.html Joel Elias Spingarn Papers] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071017131121/http://library.nybg.org/finding_guide/archv/spingarn_ppb.html |date=2007-10-17 }}</ref> He served as a member of the Board of Managers for the [[New York Botanical Garden]].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://library.nybg.org/finding_guide/archv/spingarn_ppb.html|title= Joel Elias Spingarn Papers (PP)|publisher= The New York Botanical Garden.|access-date= May 9, 2014|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20071017131121/http://library.nybg.org/finding_guide/archv/spingarn_ppb.html|archive-date= October 17, 2007|url-status= dead}}</ref> |

||

He lived with his wife, Amy Einstein Spingarn, in [[Manhattan]] and at their country estate which later became the Troutbeck Inn and Conference Center<ref>Troutbeck: [http://www.troutbeck.com/history.htm History] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080201095729/http://www.troutbeck.com/history.htm |date=2008-02-01 }}</ref> in [[Amenia, New York]]. They had two sons, including [[Stephen J. Spingarn]], and two daughters. |

He lived with his wife, Amy Einstein Spingarn, in [[Manhattan]] and at their country estate which later became the Troutbeck Inn and Conference Center<ref>Troutbeck: [http://www.troutbeck.com/history.htm History] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080201095729/http://www.troutbeck.com/history.htm |date=2008-02-01 }}</ref> in [[Amenia, New York]]. They had two sons, including [[Stephen J. Spingarn]], and two daughters. |

||

| Line 99: | Line 85: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* {{Gutenberg author | id= |

* {{Gutenberg author | id=38161| name=Joel Elias Spingarn}} |

||

* {{Internet Archive author |sname=Joel Elias Spingarn}} |

* {{Internet Archive author |sname=Joel Elias Spingarn}} |

||

{{NAACP}} |

{{NAACP}} |

||

{{Spingarn Medal}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| Line 110: | Line 96: | ||

[[Category:1939 deaths]] |

[[Category:1939 deaths]] |

||

[[Category:American Jews]] |

[[Category:American Jews]] |

||

[[Category:Columbia |

[[Category:Columbia College (New York) alumni]] |

||

[[Category:American literary critics]] |

[[Category:American literary critics]] |

||

[[Category:Columbia University faculty]] |

[[Category:Columbia University faculty]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:NAACP activists]] |

||

[[Category:New York (state) Republicans]] |

[[Category:New York (state) Republicans]] |

||

[[Category:New York (state) Progressives (1912)]] |

[[Category:New York (state) Progressives (1912)]] |

||

Latest revision as of 01:39, 19 February 2024

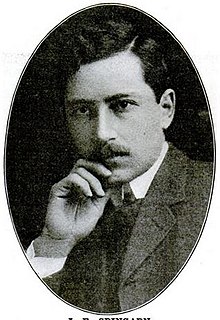

Joel Spingarn | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People | |

| In office 1930–1939 | |

| Preceded by | Moorfield Storey |

| Succeeded by | Arthur B. Spingarn |

| Chair of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People | |

| In office 1914–1919 | |

| Preceded by | Oswald Garrison Villard |

| Succeeded by | Mary White Ovington |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joel Elias Spingarn May 17, 1875 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | July 26, 1939 (aged 64) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (before 1912) Progressive (1912–1916) |

| Spouse | Amy Einstein |

| Children | 2 sons, including Stephen 2 daughters |

| Relatives | Arthur B. Spingarn (brother) |

| Education | Columbia University (BA) |

Joel Elias Spingarn (May 17, 1875 – July 26, 1939) was an American educator, literary critic, civil rights activist, military intelligence officer, and horticulturalist.

Biography[edit]

Spingarn was born in New York City to an upper middle-class Jewish family. His younger brother was Arthur B. Spingarn. He graduated from Columbia College in 1895. He grew committed to the importance of the study of comparative literature as a discipline distinct from the study of English or any other language-based literary studies.

Politics was one of his lifetime passions. In 1908, as a Republican he ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1912 and 1916, he was a delegate to the national convention of the Progressive Party. At the first of those conventions, he failed in his attempts to add a statement condemning racial discrimination to the party platform.

He served as professor of comparative literature at Columbia University from 1899 to 1911. His academic publishing established him as one of America's foremost comparativists. It included two editions of A History of Literary Criticism in the Renaissance in 1899 and 1908 as well as edited works like Critical Essays of the Seventeenth-Century in 3 volumes. He summarized his philosophy in The New Criticism: A Lecture Delivered at Columbia University, March 9, 1910.[1] There he argued against the constraints of such traditional categories as genre, theme, and historical setting in favor of viewing each work of art afresh and on its own terms.[2] Spingarn's criticism and aesthetical thought was deeply influenced by the Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce, with whom he was in correspondence since 1899. Croce had Spingarn's masterwork translated in Italian (La critica letteraria nel Rinascimento. Saggio sulle origini dello spirito classico nella letteratura moderna, trad. di Antonio Fusco, pref. di B. Croce, Laterza, Bari 1905). Their correspondence was published in Naples in 2001 (Carteggio Croce-Spingarn, a cura di Emanuele Cutinelli-Rendina, Istituto italiano per gli studi storici, Napoli, 2001).

From 1904, his role in academic politics marked him as an independent spirit—too independent for the university's autocratic president Nicholas Murray Butler. His differences with the administration ranged from personality conflicts to educational philosophy. Things came to a head in 1910, when he offered a resolution at a university faculty meeting in support of Harry Thurston Peck, a Columbia professor who had been summarily dismissed by Butler because of a public scandal involving a breach-of-promise suit. That precipitated Spingarn's dismissal just five weeks later.[3] He became part of a distinguished series of prominent academics who resigned or were dismissed during Butler's tenure as president, including George Edward Woodberry, Charles Beard, and James Harvey Robinson—all of them, like Peck and Spingarn, notable progressive scholars.

Without an academic appointment but of independent means, Spingarn continued to publish in his field much as he had before, writing, editing, and contributing to collections of essays. He was commissioned in the U.S. Army and served as a major during World War I.[4] In 1919 he was a co-founder of the publishing firm of Harcourt, Brace and Company.

He also took up the other cause of his life, racial justice. An influential liberal Republican, he helped realize the concept of a unified black movement by joining the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) shortly after its founding and was one of the first Jewish leaders of that organization, serving as chairman of its board from 1913 to 1919, its treasurer from 1919 to 1930, its second president from 1930 until his death in 1939.

In 1914 he established the Spingarn Medal, awarded annually by the NAACP for outstanding achievement by an African American.

During World War I, according to an NAACP publication, he was instrumental in seeing that "a training camp for Negro officers at Des Moines was established and about 1,000 Negro officers commissioned."[5] Spingarn also served as an intelligence officer on the Military Intelligence Board (MIB), and provided information to the government about the NAACP's membership, which had been accused of having Communist influences.[6][7]

W. E. B. Du Bois (who had been unsuccessfully recommended by Spingarn for the MIB[8]) dedicated his 1940 autobiography Dusk of Dawn to Spingarn's memory, calling him "scholar and knight."[9]

Personal life and death[edit]

Always interested in gardening, in the years following 1920 he amassed the world's largest collection of clematis—250 species—and published the results of his research on the early history of landscape gardening and horticulture in Dutchess County, New York.[10] He served as a member of the Board of Managers for the New York Botanical Garden.[11]

He lived with his wife, Amy Einstein Spingarn, in Manhattan and at their country estate which later became the Troutbeck Inn and Conference Center[12] in Amenia, New York. They had two sons, including Stephen J. Spingarn, and two daughters.

He died after a long illness on July 26, 1939. His will included a bequest to fund the Spingarn Medal in perpetuity.

Recognition[edit]

- Spingarn Senior High School in Washington, D.C.

- In 2009, Spingarn was among 12 civil rights leaders honored with images appearing on 6 American postage stamps issued to mark the centenary of the NAACP.[13]

- The Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University is named for his brother Arthur.

Works[edit]

- As Author—Scholarship

- A History of Literary Criticism in the Renaissance (1899 and 1908)

- The New Criticism: A Lecture Delivered at Columbia University, March 9, 1910 (1911)

- Creative Criticism: Essays on the Unity of Genius and Taste (1917)

- Creative Criticism and Other Essays (1931)

- As Editor

- Critical Essays of the Seventeenth-Century, 3 vols. (1908-09)

- Goethe's Literary Essays (1921)

- As Contributor

- Criticism in America, its Functions and Status: Essays by... (1924)

- Karl Vossler, ed., Mediæval Culture: An Introduction to Dante and his Times (1929)

- As Author—Poetry

- The New Hesperides, and Other Poems (1911)

- Poems (1924)

- Poetry and Religion: Six Poems (1924)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ (NY: Columbia University Press, 1911)

- ^ Marvin A. Carlson, Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984, 311-2

- ^ Michael, Rosenthal, Nicholas Miraculous: The Amazing Career of the Redoubtable Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 209ff.

- ^ "profile of Joel Elias Spingarn". NNDB.

- ^ The Crisis: "President Spingarn Dies," Sept., 1939

- ^ Ellis, Christopher M. D. (1984). 'Negro subversion' : the investigation of black unrest and radicalism by agencies of the United States government, 1917-1920 (Ph.D. thesis). University of Aberdeen.

- ^ Cockburn, Alexander (1993-04-13). "When the State Is Terrified, Citizens Beware : A Memphis reporter writing about Dr. King uncovers decades of Army spying on Americans". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2021-12-22.

- ^ Lewis, David Levering (1994). W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868–1919. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 553–560. ISBN 9780805035681. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ Lewis, David Levering (2001). W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919–1963. Henry Holt and Company. p. 472. ISBN 9780805068139. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ New York Botanical Garden: Joel Elias Spingarn Papers Archived 2007-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Joel Elias Spingarn Papers (PP)". The New York Botanical Garden. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ Troutbeck: History Archived 2008-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ United States Postal Service: "Civil Rights Pioneers Honored on Stamps"

Further reading[edit]

- B. Joyce Ross, J.E. Spingarn and the rise of the NAACP, 1911-1939 (New York: Atheneum, 1972)

- Marshall Van Deusen, J.E. Spingarn (NY: Twayne Publishers, 1970)