Southern Italy

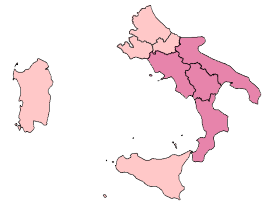

Southern Italy, often referred to as the Mezzogiorno, encompasses Basilicata, Campania, Calabria, Apulia, Abruzzo, Molise, and usually Sicily and Sardinia. Sometimes the southern part of Lazio (Parts of the provinces of Latina and Frosinone, which are linguistically, historically, and culturally tied to Southern Italy) is also included. Eurostat and the Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) usually exclude Sicily or Sardinia as Insular Italy.

The name is also applied to a former ecclesiastical province of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The term Mezzogiorno ("mèzzo" /'mɛddzo/ and "giórno" /'dʒorno/) first came into use in the nineteenth century, a comparison with the French Midi. Both mean "midday" or "noon" and are applied in this manner because the sun is directly above the southern horizon at this time of day (in the Northern Hemisphere).

Geography

Geographically the Mezzogiorno is the actual "boot" of the peninsula, containing the ankle (Abruzzo and Molise), the toe (Calabria), and the heel (the southern half of Apulia). Separating the two is the Gulf of Taranto, named after the city of Taranto, which sits at the angle between heel and "sole". It is an arm of the Ionian Sea. The rest of the southern third of the Italian peninsula is studded with smaller gulfs and inlets.

On the eastern coast is the famous Blue Adriatic, leading into the rest of the Mediterranean through the Strait of Otranto (named after the largest city on the tip of the heel). On the Adriatic, south of the "spur" of the boot, the peninsula of Monte Gargano (Policastro), the Gulf of Salerno, the Gulf of Naples, and the Gulf of Gaeta are each named after a large coastal city. Along the northern coast of the Salernitan gulf, on the south of the Sorrentine peninsula, runs the famous Amalfi Coast. Off the tip of the peninsula there is the world famous isle of Capri.

The largest city in the Mezzogiorno is Naples, a title it has historically maintained for centuries. Palermo and Bari are the next largest cities in the area.

History

Ever since the Greeks colonised Magna Graecia in the eighth and seventh centuries BCE, the south of Italy has, in many respects, followed a distinct history from the north. After Pyrrhus of Epirus failed in his attempt to stop the spread of Roman hegemony in 282 BC, the south fell under Roman domination and remained in such a position well into the barbarian invasions (the Gladiator War is a notable suspension of imperial control). It was held by the Byzantine Empire after the fall of Rome in the West and even the Lombards failed to consolidate it, though the centre of the south was theirs from Zotto's conquest in the final quarter of the 6th century.

From then to the Norman conquest of the 11th century, the south of the peninsula was constantly plunged into wars between Greek, Lombard, and the Caliphate, interrupted only by the arrival of the Normans, who, in less than one hundred years, rose to preeminence and completely subjugated the Lombard principalities, expelled the Islamic element, and removed the Byzantines from all but Naples, which gave in to the great Roger II in 1127. He raised the south to kingdom status in 1130, calling it the Kingdom of Sicily. It lasted only 64 years before the Holy Roman Emperors long-held designs on the region came to fruition. The Hohenstaufen rule ended in defeat, but the conquering French of Charles of Anjou were themselves forcibly pushed out in the event immortalized as the Sicilian Vespers. Hereafter, until the union in Spain, the kingdom was split between the principalities of Naples on the mainland and of Sicily over the island. The Aragonese rule left its impression on Italy and the Renaissance through such figures as Alfonso the Magnanimous and the Borgia clan. With the unification of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, Southern Italy and Sicily ceased to have a local monarch and were ruled by viceroys appointed by the Spanish crown.

The region remained a part of Spain until the War of the Spanish Succession, when Duke Victor Amadeus II of Sardinia took Sicily. It was soon exchanged with Austria for Sardinia. It became an independent kingdom for Charles of Bourbon and remained so until it was created the Kingdom of Naples for benefit of Napoleon's marshal Joachim Murat. An object of irredentism and the Risorgimento, the land was conquered by Giuseppe Garibaldi and the Redshirts in 1861 and, with the north, formed the modern state of Italy.

The transition to a united Italy was not smooth for the South. The Southern economy was much more agrarian and feudal than the more industrial northern economy. Because of this, the South experienced great economic difficulties resulting in massive emigration leading to a worldwide Southern Italian diaspora. Today, the South remains considerably less economically developed than the North. Southern Italian secession movements have developed, but have gained little, if any, significant influence [citation needed].

North-South Divide

The Mezzogiorno has historically been an economically underdeveloped area, roughly coextensive with the former Kingdom of Naples. Southern Italy continues to be the least prosperous area of Italy, when compared to Northern and Central Italy. Problems continue to include corruption and relatively high unemployment[citation needed]. Southern Italy includes 37% of Italy's population, occupies 40% of its land area, but only produces 24% of its GDP[citation needed].

During the 1950s the regional policy, the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno was set up to help raise the living standards in the South to those of the North. The Cassa aimed to do this in two ways: by land reforms creating 120,000 new small farms, and through the "Growth Pole Strategy" whereby 60% of all government investment would go to the South, thus boosting the Southern economy by attracting new capital, stimulating local firms, and providing employment. As a result the South became increasingly subsidized and dependent, incapable of generating growth itself. Today, in spite of increased affluence and a much improved economy, the regional disparities persist. However, even though the standard of living is still well below that of northern and central Italy, there are districts with substantial economic production. On the whole, the Mezzogiorno's per capita income has improved to the point where it is near the European Union median.[1]

Culture

Historically, the regions of the Mezzogiorno have been exposed to some different influences than the rest of the peninsula, starting most notably with the Greek colonization and the Norman invasions of Sicily and the southern mainland. It then remained part of the Byzantine Empire long after the collapse of the Roman Empire. In addition, the Mezzogiorno was subjected to rule by foreign powers, most recently ruled by the new European nation states, such as Spain and Austria. Poverty and organized crime were persistent problems in the agricultural Mezzogiorno causing much emigration from the area to many other countries, heavily contributing to the Italian diaspora. Since about 1870, many natives of the Mezzogiorno also relocated to the industrial cities in northern Italy, such as Genoa, Milan and Turin. In general, it is often said that the South of Italy is more "Mediterranean" than the rest of Italy [citation needed].happy birthday caitlin

See also

turds sisters hot