White Zimbabweans

People of European ethnic origin (“whites”) first came as settlers to the African country now known as Zimbabwe during the late nineteenth century. A steady immigration of whites followed and eventually a self-governing British colony known as Rhodesia was established. Up to the end of the 1970s whites were the dominant ethnic group in the country although their numbers never exceeded 300,000, or about 5.5% of the population.

As was the case (to varying degrees) in most European colonies in Africa and Asia, white immigrants took a high profile in many areas of society. This was mainly in those areas initiated by the immigrants themselves such as industry, commercial farming and the professions. However, the position in Rhodesia was distinguished by the fact that the local white minority entrenched its political dominance of the country. Extensive areas of prime farmland were reserved for white ownership. Senior positions in the public services were reserved for whites and whites working in manual occupations enjoyed legal protection against job competition from blacks. This situation was unwelcome to the majority ethnic groups within Zimbabwe and to wide sections of international opinion.

After the country’s independence as Zimbabwe in 1980, whites had to adjust to being an ethnic minority in a country with a black government. Many whites emigrated in the early 1980s, being uncertain about their future, but many remained and considered themselves Zimbabweans. Political unrest and the seizure of farms resulted in a further exodus commencing in 1999. The 2002 census recorded 46,743 whites remaining in Zimbabwe. More than 10,000 were elderly and less than 9,000 were under the age of 15.[1] This should be seen within the much larger trend of economic migration that has seen millions of Zimbabweans leave for other countries in Southern Africa and Europe.

Background

Zimbabwe (then known as Southern Rhodesia and later just as Rhodesia) was selected as a settlement colony by South African, British (largely Scottish) and Afrikaner colonists from the 1890s onwards, following the subjugation of the Matabele, (Ndebele), and Shona nations by the British South Africa Company (BSAC). The early white settlers came in search of mineral resources, finding deposits of coal, chromium, nickel, platinum and gold. They also found some of the best farmland in Africa. The central part of Rhodesia is a plateau which varies in altitude between 900 m and 1,500 m above sea level. This gives the area a sub-tropical climate which is conducive to European settlement and agricultural practices.[2]

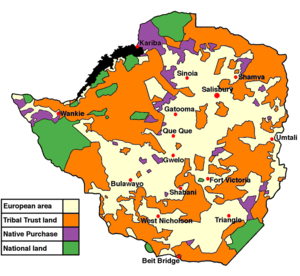

The white soldiers who assisted in the BSAC takeover of the country were each given 3,000 acre (or more) land grants, and blacks living on this land became tenants. Later, Land Apportionment and Tenure acts reserved extensive areas for either black only tribal trust lands or for white ownership, which gave rise to cases of blacks being excluded from land that they had worked for generations. White settlers were attracted to Rhodesia by the availability of tracts of prime farmland that could be purchased from the state at low cost. This resulted in a major feature of the Rhodesian economy - the "white farm". The white farm was typically a large (>100 km²) mechanised estate, owned by a white family and employing hundreds of blacks. Many white farms provided housing, schools and clinics for black employees and their families. At the time of independence in 1980, over 40% of the country's farming land was contained within 5,000 white farms. It was claimed that these farms provided 40% of the country's GDP and up to 60% of its foreign earnings.[3] Major export products included tobacco, beef, sugar, cotton and maize.

The minerals sector was also important. Gold, asbestos, nickel and chrome were mined by foreign owned concerns such as Lonhro and Anglo American. These operations were usually run by white managers, engineers and foremen.

The Census of May 3, 1921 found that Southern Rhodesia had a total population of 899,187 of whom 33,620 were Europeans, 1,998 were Coloured (mixed races), 1,250 Asiatics, 761,790 Bantu natives of Southern Rhodesia and 100,529 Bantu aliens.[4] The following year, Southern Rhodesians rejected, in a referendum, the option of becoming a province of the Union of South Africa. Instead, the country became a self-governing British colony. It never gained full Dominion status, although unlike other colonies, it was treated as a de facto Dominion, with its Prime Minister attending the Commonwealth Prime Minister's Conference.

The growth of the white community

In 1891, before Southern Rhodesia was established as a territory, it was estimated that there were about 1,500 Europeans resident there. This number grew slowly to around 75,000 in 1945. In the period 1945 to 1955 the white population doubled to 150,000. During that decade, 100,000 blacks were forcibly resettled from farming land designated for white ownership.[5] It must be noted that some members of the white farming community opposed the forced removal of blacks from land designated for white ownership and some even favoured the handover of underutilized white land to black farmers. For example, in 1947 Wedza white farmer Harry Meade unsuccessfully opposed the eviction of his black neighbour Solomon Ndawa from a 500 acre irrigated wheat farm. Meade represented Ndawa at hearings of the Land Commission and attempted to protect Ndawa from abusive, racist questioning.[6]

Large-scale white emigration to Rhodesia did not begin until after the Second World War, and at its peak in the late 1960s Rhodesia's white population consisted of as many as 270,000.[7] There were influxes of white immigrants from the 1940s through to the early 1970s. The most conspicuous group were former British servicemen in the immediate post-war period. But many of the new immigrants were refugees from communism in Europe, others were former service personnel from colonial India, others came from Kenya, the Belgian Congo, Zambia and Algeria. For a time, Rhodesia provided something of a haven for whites who were retreating from decolonisation elsewhere in Africa and Asia.[8]

However, it should be noted that whites never amounted to more than 5.5% of the country's total population (that is, 270,000 whites divided by 5 million total population in 1970[9]). Also, the white farming community never amounted to more than around 8% of the total white population and this proportion fell steadily after 1945 up to independence in 1980.

Various factors encouraged the growth of the white population of Rhodesia. These included the industrialisation and prosperity of the economy in the post-War period and the fact that the National Party victory in the 1948 South African general election made that country less friendly to British settlement and investment than was previously the case. It was also apparent as early as the 1950s that white rule would continue for longer in Rhodesia than it would in other British colonies such as Zambia (Northern Rhodesia) and Kenya. Many of the new immigrants had a "not here" attitude to majority rule and independence.

Rhodesia was run by a white minority government and in 1965 that government declared itself independent through a Unilateral Declaration of Independence ('UDI') under Prime Minister Ian Smith.[10] The UDI project eventually failed, after a period of UN economic sanctions and a civil war known as the Chimurenga (Shona) or Bush War. British colonial rule returned in December 1979 (as 'The British Dependency of Southern Rhodesia') and then the country became the independent state of Zimbabwe in April 1980.

One characteristic of white settlement in Rhodesia was that the white community kept itself largely separate from the Black and Asian communities in the country.[11] Urban whites lived in separate areas of town, and whites had their own education, healthcare and recreational facilities. Marriage between blacks and whites was possible, but remains to the present day very rare. The 1903 Immorality Suppression Ordinance made "illicit" (i.e. unmarried) sex between black men and white women illegal – with a penalty of two years imprisonment for any offending white woman.[12] The majority of the early white immigrants were men, so many white men entered into relationships with black women. The result was a large number of mixed race individuals, many of whom were accepted as being white. A proposal by Garfield Todd (Prime Minister, 1953-1958) to liberalise laws on inter-racial sex was viewed as dangerously radical. The proposal was rejected and was one factor that led to the political demise of Todd.[13]

Rhodesian whites had enjoyed a very high standard of living. The Land Tenure Act had reserved 50% of agricultural land for white ownership and black labour costs were low (around US$40 per month in 1975), which had a large effect in the context of an agricultural economy.[14] Public spending on education, healthcare and other social services was heavily weighted towards provision for whites. Most of the better paid jobs in public service were reserved for whites.[15] Whites in skilled manual occupations enjoyed employment protection against black competition.[16] In 1975, the average annual income per head for Rhodesian whites was around US$8,000 (with income tax at a marginal rate of 5%) - making them one of the richest communities in the world.[17]

At independence probably around 38% of white Zimbabweans were UK-born, with slightly fewer born in Rhodesia and around 20% from elsewhere in Africa.[18] The white population of that era exhibited a high degree of mobility and many whites might better be considered foreign expatriates than settlers. Between 1960 and 1979 white immigration to Rhodesia was 180,000 and white emigration in the same period was 202,000 (with an average white population of around 240,000).[19] Many whites were relatively recent arrivals in the country and showed little hesitation about moving on after independence.

Post Independence

The country gained its independence as Zimbabwe in April 1980, under a ZANU-PF government lead by Robert Mugabe.

The status of the whites

Following independence, the country's whites lost their former privileged position. A generous social welfare net (including both education and healthcare) that had supported whites in Rhodesia disappeared almost in an instant. Whites in the artisan, skilled worker and supervisory classes began to experience job competition from blacks. Indigenisation in the public services displaced many whites. The result was that white emigration gathered pace. In the ten year period from 1980 to 1990 approximately 2/3 of the white population left Zimbabwe.[20]

However, many whites resolved to stay in the new Zimbabwe. Only 1/3 of the white farming community left and an even smaller proportion of white urban business owners left.[21]

A 1984 article in the Sunday Times Magazine described and pictured the life of Zimbabwean whites at a time when their number was just about to fall below 100,000.[22] About 49 per cent of emigrants left to settle in South Africa, many of whom were Afrikaans speakers, 29 per cent in the United Kingdom and most of the remainder going to Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States.[23] Many of these emigrants identify themselves as Rhodesian. A white Rhodesian/Zimbabwean who is nostalgic for the UDI era is known colloquially as a "Rhodie". These nostalgic "Rhodesians" are also sometimes referred to as "Whenwes", because of the nostalgia of "when we were in Rhodesia"[24] A white who remained in Zimbabwe and took a modern outlook is known as a "Zimbo".

The lifting of UN imposed economic sanctions and the end of the Bush War at the time of independence produced an immediate 'peace dividend'. Renewed access to world capital markets made it possible to finance major new infrastructure developments in transport and schools. One area of economic growth was tourism, catering in particular to visitors from Europe and North America. Many whites found work in this sector. Another area of growth was horticulture, involving the cultivation of flowers, fruits and vegetables which were air-freighted to market in Europe. Many white farmers were involved in this and in 2002 it was claimed that 8% of horticultural imports into Europe were sourced in Zimbabwe.[26] The economic-migrant element among the white population had departed quickly after independence, leaving behind those whites with deeper roots in the country. The country settled and the white population stabilised.

It should be noted that the 1979 Lancaster House Agreement, which was the basis for independence, had precluded any meaningful form of compulsory land redistribution for a period of at least 10 years. The pattern of land ownership established during the Rhodesian state therefore survived for some time after independence. Those whites who were prepared to adapt to the situation they found themselves in were therefore able to continue enjoying a very comfortable existence. In fact, the independence settlement combined with favourable economic conditions plus ESAP (see below) produced a 20 year period of unprecedented prosperity for Zimbabwean whites and for the white farming community in particular. A new class of "young white millionaires" appeared in the farming sector.[27] These were typically young Zimbabweans who had applied skills learned in agricultural colleges and business schools in Europe.

"This is the best government for commercial farmers that this country has ever seen" John Brown (CFU president), 1989[28]

White Zimbabweans with professional skills were readily accepted in the new order. For example, Chris Andersen had been the hardline Rhodesian justice minister but made a new career for himself as an independent MP and leading attorney in Zimbabwe. In 1998 he defended former President Canaan Banana in the infamous "sodomy trial".[29] At the time of this trial, Andersen spoke out against the homophobic attitude of President Mugabe who had described gays as being "worse than dogs and pigs since they are a colonial invention, unknown in African tradition".[30]

Land

By the mid-1990s it is thought that around 70,000 whites remained in Zimbabwe.[31] In spite of this small number, the white Zimbabwean minority maintained control of much of the economy through its investment in commercial farms, industry and tourism. However, an on-going programme of land reforms (intended to alter the ethnic balance of land ownership) dislodged many white farmers. The level of violence associated with these reforms in some rural areas made the position of the wider white community uncomfortable. Twenty years after independence, there were 21,000 commercial farmers in the country of whom 4,000 were white and 17,000 were black.[32] Natural market processes had diminished the influence of white farmers to a point where the government was no longer afraid to confront them.

The "land issue" is a problem that came to assume a very high profile in Zimbabwe's political life. ZANU politicians pressed for land to be transferred from white to black ownership regardless of the resultant disruption to agricultural output, in order to correct the injustice of the Rhodesian land apportionment; much of this land was redistributed to party cronies and loyalists of the Mugabe regime. White farmers argued that this served little purpose since Zimbabwe has ample agricultural land much of which was either vacant or only lightly cultivated. On this last basis, the problem was really a lack of development rather than one of land tenure. White farmers would respond to claims that they owned "70% of the best arable land" by stating that what they actually owned was "70% of the best developed arable land" - and the two are entirely different things.[33] Whatever the merits of the arguments, in the post-Independence period the Land Issue assumed enormous symbolic importance to all concerned. As the euphoria of independence subsided and as a variety of economic and social problems became evident in the late 1990s, the Land Issue became a focus for trouble.

In 1999 the government initiated a "fast track land reform" programme. This was intended to transfer 4,000 white farms, covering 110,000 km² of mostly prime farmland, to black ownership. The means used to implement the programme were ad-hoc and involved forcible seizure in many cases.[34]

By mid-2006 only 500 of the original 5,000 white farms were still operational.[35] The majority of the white farms that avoided expropriation were in Manicaland and Midlands where it proved possible to do local deals and form strategic partnerships. However, by early 2007, a number of the farms were being leased back to their former white owners and it is expected that as many as 1,000 of them could be operational again, in some form, by the end of the year.[36] Most of the evicted white farmers are still in Zimbabwe and are turning their hands to new enterprises. One former white farmer formed a construction company and used his bulldozers to demolish township shacks for the government as part of Operation Murambatsvina.[37]

While the expropriated white farmers themselves have generally moved on to other things, this has not been the case for some of their employees. Former white farm workers from the chargehand/foreman bracket have found themselves in much reduced circumstances. The post 2000 recession has seen the emergence of a class of "poor whites". These are typically individuals who lack capital, education and skills - and who are therefore unable to migrate from Zimbabwe. Social workers have commented that blacks facing difficulties are usually able to fall back on support from extended families. Whites and coloureds have a much more individualistic culture and appear less able to cope with hardship.[38]

A University of Zimbabwe sociologist told IWPR journalist Benedict Unendoro, the esprit de corps of the white dominant class in the former Rhodesia prevented the poor whites from becoming a recognizable social group because of the social assistance provided by the dominant social class on racial grounds. This system broke down after the founding of Zimbabwe, causing the number of poor whites to increase especially after 2000, when the confiscation of white-owned farms took its toll. As rich white land owners emigrate or fend for themselves financially, their white employees who mainly worked as supervisors of black labour, found themselves destitute on the streets of cities like Harare, with many found begging around urban centres like Eastlea.

Some of the land lost to white ownership had been redistributed to black peasant farmers and smallholders. Some had been acquired by commercial land companies. A substantial portion has been transferred to individuals connected to the regime. The lack of professional management skills among the new landowners has meant a dramatic decline in agricultural production; once self-sufficient, Zimbabwe is now a net importer of food.

White millionaires

66 year old John Bredenkamp started his trading business during the UDI era when he developed expertise in “sanctions busting”. He is reported to have arranged the export of Rhodesian tobacco and the import of components (including parts and munitions for the UDI regime’s force of Hunter jets) in the face of UN trade sanctions. Bredenkamp was able to continue and expand his business after independence, making himself a personal fortune estimated at around US$1,000m.[39]

A number of foreign white entrepreneurs have been attracted to Zimbabwe in recent years. Controversial British businessman Nicholas van Hoogstraten has built up a 4200 km² land holding in central Zimbabwe through his corporate interests (mainly Messina Investments). Far from losing land to resettlement, van Hoogstraten has actually been able to purchase new property since 2000. Van Hoogstraten, a man with a colourful and criminal history,[40] has described President Mugabe as “100 percent decent and incorruptible” and “a true English gentleman”.[41] Van Hoogstraten is reported to have arranged supplies for Zimbabwean forces in the DRC and to have underwritten arms deals for the Mugabe regime.[42]

Several white Zimbabwean businessmen, such as Billy Rautenbach, have returned to their native country after working abroad for some years. Rautenbach has succeeded in extending Zimbabawean minerals sector activity into neighbouring countries such as the DRC.[43]

Charles Davy is one of the largest private landowners in Zimbabwe. 53 year old Davy is reported to own 1,200 km² of land including farms at Ripple Creek, Driehoek, Dyer's Ranch and Mlelesi. His property has been almost unaffected by any form of land redistribution - and he denies that this fact has any link to his business relationship with MP and Minister Webster Shamu. Says Davy about Minister Shamu "I am in partnership with a person who I personally like and get along with".[44] Other views on Shamu are less kind.[45]

Davy is married to Beverley, a former model and "Miss Rhodesia" of 1973. Their daughter Chelsy (born and raised in Bulawayo) is the long-standing girlfriend of Prince Harry. Press reports[46] quote Chelsy's Uncle Paul as saying that although Harry and Chelsy wished to marry, the British Royal Family would not allow this because of Chelsy's Zimbabwean nationality. Chelsy may not have helped her own case by participating a little too enthusiastically in Prince Harry's celebration of his graduation from the Sandhurst military academy in 2006 and dressing inappropriately.

The political environment in Zimbabwe has allowed the development of an exploitative business culture, in which white businessmen have played a prominent role.[47][48] When Zimbabwe was subject to EU sanctions arising from its involvement in the DRC from 1998, the government was able to call on sanctions busting expertise and personnel from the UDI era to provide parts and munitions for its force of Hawk jets. It has been suggested that, in spite of 25 years of ZANU-PF government, Zimbabwe has become a congenial place for white millionaires to live and do business in.[49]

Sports

Prior to independence, Rhodesian/Zimbabwean representation in international sporting events was almost exclusively white. Zimbabwean participation in some international sporting events continued to be white dominated until well into the 1990s. For example, no black player was selected for the Zimbabwean cricket team until 1995.[50] Rally driver Conrad Rautenbach (son of Billy, see above) won the FIA African Championship scoring Dunlop Zimbabwe Challenge Rally in 2005 and 2006.[51]

As of 2007, a still disproportionate number of Zimbabwe's most famous athletes are white. In tennis, the Black family of Cara, Byron and Wayne Black are all ranked among the top doubles players in the world. Zimbabwe's National Cricket Team has several white players including Brendan Taylor and Sean Williams. Also, Zimbabwe's most successful recent Olympic athlete is swimmer Kirsty Coventry, who won three medals (including gold) at the 2004 Summer Olympics.

The involvement of whites in Zimbabwean politics

Political and economic background

During the UDI era, Rhodesia developed a siege economy as the means of withstanding UN sanctions. The country operated a strict system of exchange and import controls, while major export items were channelled through state trade agencies (such as ‘the Grain Marketing Board’). This approach was continued until around 1990, at which time International Monetary Fund and World Bank development funding was made conditional upon the adoption of economic liberalisation. In 1991 Zimbabwe adopted ESAP (Economic Structural Adjustment Programme) which required privatisation, the removal of exchange and import controls, trade deregulation and the phasing out of export subsidies.[53] Up to the time of independence, the economy relied mainly on the export of a narrow range of primary products including tobacco, asbestos and gold. In the post independence period, the world markets for all these products deteriorated and it was hoped that ESAP would facilitate diversification.[54]

ESAP and its successor ZIMPREST (Zimbabwe Programme for Economic and Social Transformation) caused considerable economic turbulence.[55] Some sectors of the economy did benefit. But the immediate results included job losses, a rise in poverty and a series of exchange rate crises. The associated economic downturn caused the budget deficit to rise which put pressure on public services. The means used to finance the budget deficit have caused hyperinflation. These factors created a situation in which many bright and qualified Zimbabweans (both black and white) had to look abroad for work opportunities.[56] Zimbabwean politics since 1990 have therefore been conducted against a background of economic difficulty with the manufacturing sector (in particular) being 'hollowed out'. Although, some parts of the economy continue to perform well. The Zimbabwe stock exchange and the property market have experienced minor booms, while outsiders are coming to invest in both mining and land operations. Where some see crisis, others see opportunity.[57]

In the period immediately after independence, white political leaders (such as Ian Smith) sought to maintain the identity of Zimbabwe whites as a separate or apartheid group. In particular, they sought to maintain a separate "white roll" for the election of 20 seats in parliament reserved for whites (abolished in 1987). Although, not all whites went along with this and many actually joined ZANU-PF. For example, Timothy Stamps served as Minister of Health in the Zimbabwe government from 1986 to 2002. Even his critics accept that Stamps was motivated by a desire to improve the lot of poorer people.

Rich Zimbabweans

More recently, an elite network of white businessmen and senior military officers has been associated with a faction of ZANU-PF identified with Emmerson Mnangagwa, formerly Security Minister and later Speaker of Parliament. Mnangagwa has been described as "the richest politician in Zimbabwe".[58] He is believed to have favoured the early retirement of President Mugabe and a conciliatory approach towards the regime's domestic opponents. This line has displeased other elements in ZANU-PF. In June 2006, John Bredenkamp (a prominent former Mnangagwa associate) fled Zimbabwe in his private jet after government investigations into the affairs of his Breco trading company were started.[59] Bredenkamp returned to Zimbabwe in September 2006 after his passport was returned by court order.[60]

In July 2002, 92 prominent Zimbabweans were subject to EU "smart sanctions" intended to express disapproval of various Zimbabwe government policies. These individuals were banned from the EU and access to assets they own in the EU was frozen.[61] 91 of those on the blacklist were black and 1 was white. The single white was Dr Timothy Stamps.

Many observers found the EU's treatment of Dr Stamps to be curious, given that by July 2002 he was retired from active politics and a semi-invalid. Also, Stamps was widely rated to be a highly dedicated doctor who had never been implicated in any form of wrongdoing.[62] The same observers found it equally curious that the EU Commission did not include the wealthy white backers of Mugabe on the list.[63]

The MDC and the 2000 general election

From around 1990, mainstream white opinion favoured opposition politics as whites sought to maintain their position in the country through support for liberal economics, democracy and the rule of law. Whites played a leading role in the funding and management of the opposition MDC party after 1999. Roy Bennett, a white farmer forced off his coffee plantation after it was overrun by radical militants and then expropriated, won a strong victory in the Chimanimani constituency (adjoining the Mozambican border) in the 2000 general election. Bennett (a former Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe member) won his seat for the Movement for Democratic Change, and was one of four white MDC constituency MPs elected in 2000.[64][65] Bennett was excluded from Parliament and imprisoned after he physically assaulted the Attorney General on the floor of the House.

Other white MPs elected in 2000 included David Coltart (a former Rhodesian police officer) and Michael Auret (a civil rights activist of long standing who had opposed white minority rule in the 1970s). Trudy Stevenson was a Ugandan white who had come to Rhodesia in 1972. Stevenson served as the MDC's Secretary for Policy and Research before being elected to Parliament. In July 2006, after attending a political meeting in the Harare suburb of Mabvuku, Mrs Stevenson was attacked and suffered panga wounds to the back of her neck and head. The MDC leadership immediately claimed that the attack was carried out by ZANU militants. But, while recovering in hospital, the MP for Harare North positively identified her assailants as members of a rival faction of the MDC. This serves to illustrate the violent and faction ridden nature of Zimbabwean politics.[66] Zimbabwean politicians (black and white) routinely accuse each other of murder, theft, electoral fraud, conspiracy and treason. It is often difficult to know the truth of these matters.[67]

One of the most prominent MDC spokesmen is Eddie Cross.[68] Cross is a leading Zimbabwean business figure and serves as the MDC's Economic Secretary and shadow finance minister. Although critical of the ZANU-PF government, Cross has always been an advocate of the economic liberalisation that the government has introduced.

The 2000 general election was arguably the most significant event in post-independence Zimbabwean politics. It was the first seriously contested election in the country since 1962 and was fought out against a background of intractable economic, social and political problems. The ZANU ruling party had been in power for 20 years and was widely considered to have run out of ideas.[69] Whites played a leading role in the campaign of the opposition MDC which almost won the election.[70] Radical elements in the country perceived the MDC project to have been an attempt to restore a limited form of white minority rule and this produced a violent backlash.[71][72]

Current developments

White emigration - particularly from within the farming community - picked up speed again after 2000. There is a link between the recent economic decline in Zimbabwe and white emigration, although which is cause and which is effect is open to debate. There has been an enormous black emigration in the same period. By 2006, some estimates were that the white population of Zimbabwe could have fallen to little more than 80,000.[73] However, the figure may be misleading since there is a large community of white Zimbabweans who work abroad on a contract basis or have moved their businesses abroad - while retaining a home in the country. One view is that the white population of Zimbabwe has been surprisingly resilient, and any improvement in the economic and political climate would bring many expatriates home again.

The Independence constitution contained a provision requiring the Zimbabwean government to honour pension obligations due to former servants of the Rhodesian state. This obligation included payment in foreign currency to pensioners living outside Zimbabwe (almost all white). Pension payments were made until the 1990s, but they then became erratic and stopped altogether in 2003.[74]

White communities in African countries suffered a variety of fates in the post-colonial period. In many countries (eg Kenya and Namibia) the white communities survived and actually grew in number. In two particular cases, Algeria and Zimbabwe, the previously large white communities have shrunk. In both these last cases, the white communities had put up a fight against decolonisation and many whites found it difficult to adjust to the realities of the world they found themselves in after independence. Many neutral observers feel that the failure of some newly independent African countries and their white minorities to come to terms with one another was to the mutual disadvantage of both parties. For example, refugee white farmers and hoteliers from Zimbabwe have done much to right the economic situation in nearby Zambia.[75][76] Although much depleted in numbers, white Zimbabweans continue to play a leading role in the country's economic and political life.

White Zimbabweans/Rhodesians are now scattered around the world, with concentrations in the UK, Australia, South Africa and Canada. They maintain contact with each other through associations and websites. On 11 November 1990, expatriate Rhodesians around the world met at parties to celebrate the 25th anniversary of UDI. Similar parties were held in 2005 to celebrate the 40th anniversary of UDI - but these were far less well attended and less exuberant in mood.

In the late evening of March 31, 2007, Zimbabwean police raided a club in an affluent and predominantly white Harare suburb and many of Zimbabwe's few remaining white young people were assaulted and detained. A few were taken to hospital and those interviewed said that this event among others is pushing the small white community past its limits.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Irish Examiner report:2002 census returns

- ^ This is a journey:the geography of Zimbabwe

- ^ Multinational Monitor, April 1981 :Zimbabwe's government wins confidence

- ^ Official Year Book of the Colony of Southern Rhodesia, No. 1, 1924 (Art Printing and Publishing Works, Salisbury, 1924)

- ^ Selby thesis:p60

- ^ Selby thesis:p52

- ^ Selby thesis:p62, fig 1.6

- ^ Selby thesis:p58

- ^ Demographics of Zimbabwe

- ^ BBC report:UDI of Rhodesia, 1965

- ^ "From Civilization to Segregation: Social ideals and social control in Southern Rhodesia, 1890-1934" by Carol Summers, Ohio University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8214-1074-1

- ^ Gender and History, 2005 :article by Lucy Bland on black-white sex, see p3

- ^ Guardian: Obituaries: Sir Garfield Todd

- ^ AFP Report on Rhodesia, 1976 :Robin Wright, para 38

- ^ "The Governmental System of Southern Rhodesia", by D.J. Murray, OUP, 1970

- ^ Selby thesis:p66

- ^ Propaganda: The Other Rhodesian War

- ^ "A Chronicle of Modern Sunlight", author W.G. Eaton published by Innovision, Rohnert Park, California, 1996

- ^ Ian F. W. Beckett, The Rhodesian Army: Counter-Insurgency 1972-1979 (paragraph 17)

- ^ Selby thesis:p117, fig2.3

- ^ Selby thesis:p125

- ^ Sunday Times Magazine:1984 report on whites in Zimbabwe

- ^ W.G. Eaton, A Chronicle of Modern Sunlight, published by Innovision, Rohnert Park, California, 1996

- ^ "Rhodie oldies". New Internationalist. 1985. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ World Hockey:golden memories

- ^ SADC newsletter: Eddie Cross interview

- ^ Selby thesis:p194

- ^ Selby thesis:p126

- ^ NewsPlanet, June 1998 :Sodomy Laws

- ^ Electronic Mail:"Faggots"

- ^ Selby thesis p62, fig1.6

- ^ SADC newsletter: Eddie Cross interview, see Q2

- ^ Online :the Zimbabwean Land Issue

- ^ Human Rights Watch report Fast Track Land Reform

- ^ Selby thesis p318

- ^ The Guardian, 4 January 2007 Mugabe lets white farmers back

- ^ Selby thesis p325

- ^ Mopane Tree:"poor whites" in Zimbabwe

- ^ The Guardian, 9 June 2006: Tycoon flees Zimbabwe in private jet

- ^ The Observer, 15 January 2006 :van Hoogstraten interview with Lyn Barber

- ^ Guardian, 21 April 2000 :British Multimillionaire bankrolls Mugabe party

- ^ Selby thesis:p324

- ^ Zimnews :report on Billy Rautenbach

- ^ Daily Telegraph report:Charles Davy defends business interests

- ^ The Zimbabwean 2005 :see para 5

- ^ Mail on Sunday, 19 December 2004

- ^ UN report:- Zimbabwe involvement in DRC minerals

- ^ House of Commons, 18 November 2002 :debate on Zimbabwe

- ^ The Zimbabwean, 2005 :business backers of ZANU-PF

- ^ Henry Olonga website:first black cricket player for Zimbabwe

- ^ Motorsport, July 2006 :Zimbabwean Conrad Rautenbach secures victory

- ^ Vermeulen:accused of arson

- ^ PRF paper:Moses Tekere

- ^ News 24, January 2007 :Zimbabwe, a Banutustan

- ^ AfricaFiles 1996:ESAP's fables, report on ESAP

- ^ Report on brain drain from Zimbabwe

- ^ Guardian April 2006 :report on Zimbabwe stock exchange

- ^ AIM article:January 2005

- ^ newzimabwe.com :political and financial dealings of Bredenkamp

- ^ The Times, 19 October 2006 :British SFO investigate Bredenkamp

- ^ UN press release, 2002 :EU names Zimbabwe blacklist

- ^ Remembering Zimbabwe, by Dr Amitabh Mitra:Stamps "the most dedicated doctor I had come across"

- ^ Daily Telegraph report:see para 8 onwards

- ^ BBC: Winners and losers

- ^ Sokwanele: Roy Bennett released

- ^ Guardian, 5 July 2006 :MDC faction attack politicians

- ^ New Zimbabwe.com :MDC supporters attack Mrs Stevenson

- ^ Africanbios: Eddie Cross biography

- ^ The Guardian, 17 March 2000 :People are sick of Mugabe

- ^ BBC report on 2000 election:Winners and Losers

- ^ William Pomeroy speech: caution, partisan account of 2000 election

- ^ BBC report, October 2000 :Mugabe under pressure

- ^ AR report:caution, partisan comment

- ^ UK Parliament: Letter to the Clerk of the Committee from Mr Barry Lennox, 15 July 2004

- ^ The Guardian, 27 February 2006 :Zimbabwean farmers in Zambia

- ^ The Guardian, 22 July 2006 :Zambian tourism sector grows at expense of Zimbabwe

External links

- The Viscount disasters of 1978 and 1979

- Rhodesians Worldwide

- BBC report on 1965 Rhodesian general election

- The Zimbabwean Land Issue

- Zimbabwean refugee farmers help to transform Zambian economy (The Guardian)

- Sunday Times (London) 1984 report on whites in Zimbabwe

- Selby, Angus (2006) “White Farmers in Zimbabwe, 1890-2005”, PhD Thesis, Oxford University

Audio and Video

- Sweet Banana, song of the RAR regiment (recorded 1978)

- Harare in 1967, hardly a black face in sight: "Suddenly - a City" You Tube

- Zimbabwe tourism promotion video from 1995 :"Zimbabwe at its best" You Tube

- ZTV commercial for Bata trainers, 1988 :YouTube

See also

- Anglo-African

- White African

- Rhodesia

- Rhodie

- Zimbabwean cricket team

- Zimbabwe Cricket

- Whites in South Africa

- Blood Diamond (film), fictional portrayal of a white Rhodesian by Leonardo DiCaprio as the protagonist